Dr. F.G. Hoffman is a Senior Research Fellow in the Center for Strategic Research, Institute for National

Strategic Studies, at the National Defense University. The author would like to thank Dr. T.X. Hammes,

Dr. Williamson Murray, and Colonel Pat Garrett, USMC (Ret.), for input on this article.

To paraphrase an often ridiculed comment made by former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, you go to war with the joint force you have, not necessarily the joint force you need. While some critics found the quip off base, this is actually a well-grounded historical reality. As one scholar has stressed, “War invariably throws up challenges that require states and their militaries to adapt. Indeed, it is virtually impossible for states and militaries to anticipate all of the problems they will face in war, however much they try to do so.”1 To succeed, most military organizations have to adapt in some way, whether in terms of doctrine, structure, weapons, or tasks.

USS Steelhead (SS-280) refitted with 5.25-inch deck gun, April 10, 1945 (retouched by wartime censors) (U.S. Navy)

The Joint Staff’s assessment of the last decade of war recognizes this and suggests that U.S. forces can improve upon their capacity to adapt.2 In particular, that assessment calls for a reinvigoration of lessons learned and shared best practices. But there is much more to truly learning lessons than documenting and sharing experiences immediately after a conflict. If we require an adaptive joint force for the next war, we need a common understanding of what generates rapid learning and adaptability.

The naval Services recently recognized the importance of adaptation. The latest maritime strategy, signed by the leadership of the U.S. Marine Corps, Navy, and Coast Guard, defines the need to create “a true learning competency,” including “realistic simulation and live, virtual, and constructive scenarios before our people deploy.”3 History teaches that learning does not stop once the fleet deploys and that a true learning competency is based not only on games, drills, and simulations but also on a culture that accepts learning and adaptation as part of war.

This lesson is ably demonstrated by the Navy’s refinement of wolf pack tactics during the Pacific campaign of World War II. The tragic story of defects in U.S. torpedoes is well known, but the Navy’s reluctant adoption of the German U-boat tactics against convoys is not often studied.4 There are lessons in this case study for our joint warfighting community.

The success of the U.S. submarine force in the Pacific is a familiar story. The Sailors of the submarine fleet comprised just 2 percent of the total of U.S. naval manpower, but their boats accounted for 55 percent of all Japanese shipping losses in the war. The 1,300 ships lost included 20 major naval combatants (8 carriers, 1 battleship, and 11 cruisers). Japanese shipping lost 5.5 million tons of cargo, with U.S. submarines accounting for almost 5 million tons.5 This exceeded the total sunk by the Navy’s surface vessels, its carriers, and the U.S. Army Air Corps bombers combined. By August 1944, the Japanese merchant marine was in tatters and unable to support the needs of the civilian economy.6 The submarine campaign (aided by other joint means) thoroughly crippled the Japanese economy.7

This critical contribution was not foreseen during the vaunted war games held in the Naval War College’s Sims Hall or during the annual fleet exercises in the decades preceding the war. Perhaps the Navy hoped to ambush some Japanese navy ships, but the damage to Japanese sea lines of communication was barely studied and never gamed, much less practiced. A blockade employing surface and submarine forces was supposed to be the culminating phase of War Plan Orange, the strategic plan for the Pacific, but it was never expected to be the opening component of U.S. strategy. Submarines were to be used as scouts to identify the enemy’s battle fleet so the modern dreadnoughts and carrier task forces could attack. Alfred Thayer Mahan had eschewed war against commerce, or guerre de course, in his lectures, and his ghost haunted the Navy’s plans for “decisive battles.”8

The postwar assessment from inside the submarine community was telling: “Neither by training nor indoctrination was the U.S. Submarine Force readied for unrestricted warfare.”9 Rather than supporting a campaign of cataclysmic salvos by battleships or opposing battle lines of carrier groups, theirs was a war of attrition enabled by continuous learning and adaptation to create the competencies needed for ultimate success. This learning was not confined to material fixes and technical improvements. The story of the torpedo deficiencies that plagued the fleet in the first 18 months of the Pacific war has been told repeatedly, but the development of the Navy’s own wolf pack tactics is not as familiar a tale. Yet this became one of the key adaptations that enabled the Silent Service to wreak such havoc upon the Japanese war effort. Ironically, a Navy that dismissed commerce raiding, and invested little intellectual effort in studying it, proved ruthlessly effective at pursuing it.10

Learning Culture

One of the Navy’s secret weapons in the interwar era was its learning culture, part of which was Newport’s rigorous education program coupled with war games and simulations. The interaction between the Naval War College and the fleet served to cycle innovative ideas among theorists, strategists, and operators. A tight process of research, strategic concepts, operational simulations, and exercises linked innovative ideas with the realities of naval warfare. The Navy’s Fleet Exercises (FLEXs) were a combination of training and experimentation in innovative tactics and technologies.11 Framed against a clear and explicit operational problem, these FLEXs were conducted under unscripted conditions with opposing sides. Rules were established for evaluating performance and effectiveness, and umpires were assigned to regulate the contest and gauge success at these once-a-year evolutions.

Torpedoed Japanese destroyer IJN Yamakaze photographed through periscope of USS Nautilus, June 25, 1942 (U.S. Navy)

Conceptually framed by war games, these exercises became the “enforcers of strategic realism.”12 They provided the Navy’s operational leaders with a realistic laboratory to test steel ships at sea instead of cardboard markers on the floor at Sims Hall. Unlike so many “live” exercises today, these were remarkably free-play, unscripted battle experiments. The fleet’s performance was rigorously explored, critiqued, and ultimately refined by the men who would actually implement War Plan Orange.13 Both the games and exercises “provided a medium that facilitated the transmission of lessons learned, nurtured organizational memory and reinforced the Navy’s organizational ethos.”14 Brutally candid postexercise critiques occurred in open forums in which junior and senior officers examined moves and countermoves. These reflected the Navy’s culture of tackling operational problems in an intellectual, honest, and transparent manner. The Navy benefited from the low-cost “failures” from these exercises.15

Limitations of Peacetime

The exercises, however, had peacetime artificialities that reduced realism and retarded the development of the submarine. These severely limited Navy submarine offensive operations in the early part of World War II.16 With extensive naval aviation participation, the exercises convinced the fleet that submarines were easily found from the air. Thus, the importance of avoiding detection, either from the air or in approaches, became paramount. In the run-up to the war, the Asiatic Squadron commander threatened the relief of submarine commanders if their periscopes were even sighted in exercises or drills.17 This belief in the need for extreme stealth led to the development of and reliance on submerged attack techniques that required commanders to identify and attack targets from under water based entirely on sound bearings. Given the quality of sound detection and sonar technologies of the time, this was a precariously limited tactic of dubious effectiveness.

Technological limitations restricted the Navy’s appreciation for what the submarine could do. The Navy’s operational plans were dominated by high-speed carrier groups and battleships operating at no less than 17 to 20 knots for extended periods, but the Navy’s interwar boats could not keep pace. They were capable of 12 knots on the surface and half that when submerged. They would be far in the wake of the fleet during extended operations. This inadvertently promoted plans to use submarines for more independent operations, which eventually became the mode employed against Japanese commercial shipping in the opening years of the war.

Though they were a highly valuable source of insights at the fleet and campaign levels, the FLEXs had not enforced operational or tactical realism for the submarine crews at the tactical/procedural level. In fact, a generation of crews never heard a live torpedo detonated, proving a perfect match for a generation of torpedoes that were never tested.18 Nor did the Navy practice night attacks in peacetime, although it was quite evident well before Pearl Harbor that German night surface attacks were effective.19 Worse, operating at night was deemed unsafe, and thus night training was overlooked before the war.20 The submarine community’s official history found that the “lack of night experience saddled the American submariners entering the war with a heavy cargo of unsolved combat problems.”21 Once the war began, however, the old tactics had to be quickly discarded, and new attack techniques had to be learned in contact.

Overall, while invaluable for exploring naval aviation’s growing capability, the exercises induced conservative tactics and risk avoidance in the submarine world that were at odds with what the Navy would eventually need in the Pacific. As one Sailor-scholar observed:

Submarines were to be confined to service as scouts and “ambushers.” They were placed under restrictive operating conditions when exercising with surface ships. Years of neglect led to the erosion of tactical expertise and the “calculated recklessness” needed in a successful submarine commander. In its place emerged a pandemic of excessive cautiousness, which spread from the operational realm into the psychology of the submarine community.22

Unrestricted Warfare

Ultimately, as conflict began to look likely, with a correlation of forces not in America’s favor, students and strategists at Newport began to study the use of the submarine’s offensive striking power by attacking Japan’s merchant marine.23 During the spring semester of 1939, strategists argued for the establishment of “war zones” around the fleet upon commencement of hostilities. These areas would be a type of diplomatic exclusion zone, ostensibly to support fleet defense during war. However, the proponents’ intent was to conduct unrestricted warfare aimed at Japan’s long and vulnerable shipping lines.24

Yet there was a gap between what submarines could do and what the emergent plans to conduct unrestricted warfare were calling for. Well before Pearl Harbor, the Navy’s senior leaders understood that unrestricted warfare was a strategic necessity. However, the implications of this change were not acted upon at lower levels in the Navy in the brief era before Pearl Harbor. Doctrine, training, and ample working torpedoes were all lacking. This created the conditions for operational adaptation under fire later.

The Campaign

Due to an insufficient number of boats, limited doctrine, and faulty torpedoes, the submarine force could not claim great success. By the end of 1942, the Pacific Fleet had sent out 350 patrols. Postwar analyses credit these patrols with 180 ships sunk, with a total of 725,000 tons of cargo.25 Although this sounds impressive, over the course of the year, the Navy had sunk the same amount as the German U-boats had in just 2 months in the North Atlantic. This level of achievement was against a Japanese navy that had limited antisubmarine warfare (ASW) expertise and little in the way of radar. The damage inflicted had no impact on Japan’s import of critical resources and commodities, and the campaign could not be seen as a success. The war’s senior submariner, Vice Admiral Charles Lockwood, admitted that the submarine force was operating below its potential contribution.26

Tasked with the ruthless elimination of Japanese shipping, the Pacific Fleet was not producing results fast enough. Some of this shortfall was the result of faulty weapons, and some was attributed to the cautious doctrine of the interwar era. Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Ernest King directed a new approach. He wrote to Admiral Chester Nimitz at Pearl Harbor on April 1, 1943, noting that “effectiveness of operations and availability of submarines indicate desirability, even necessity, to form a tactical group of 4 to 6 submarines trained and indoctrinated in coordinated action for operations such as now set up in Solomons, to be stationed singly or in groups in enemy ship approaches to critical areas.”27 Nimitz immediately directed the implementation of King’s suggestion.28 Interestingly, despite his experience combating U-boats in the Atlantic and protecting the vital sea lines of communication to Europe, King was still oriented toward the employment of submarines against Japanese naval combatants. But in line with the pre–Pearl Harbor vision of unrestricted warfare, the U.S. submarine force was following a strategy of attrition against Tokyo’s merchant shipping, and the Navy submarine force continued to emphasize individual patrols and independent command. They had not been successful in dealing with Japanese warships in critical battles such as Midway. King apparently believed that if they could be properly “trained and indoctrinated in coordinated action,” this shortcoming might be rectified.

At the same time, King was fully engaged with responding to German Kriegsmarine wolf pack tactics, or Rudeltaktik. He was painfully aware how effective they were and was being strongly encouraged by both President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill to adopt defensive measures since the U-boats critically impaired Great Britain’s war effort.29 Moreover, King was aware that the U.S. Navy was not generating the same aggregate tonnage results as the German navy, and he may have concluded that emulating the Germans could produce better results.30 Lockwood, the commander of Submarine Force Pacific (COMSUBPAC), was certainly well aware of the comparisons; in mid-1942, he wrote that “Germans getting 3 ships a day, Pac not getting one ship.”31 Furthermore, his predecessor as COMSUBPAC issued a five-page summary of German wolf pack tactics via a widely distributed bulletin in January 1943.32

Comparisons between theaters may have driven King to propose the shift, but he may have also detected trends in Japanese ASW that would eventually weaken U.S. submarine effectiveness if changes were not put in place. The operational and tactical context facing the submarine force was increasing in complexity. By 1943, Japanese convoys were becoming larger, more organized, and better protected. The escort command was employing more airplanes and newer techniques for detection and attack.

As Lockwood noted in his memoir, collective action was not unknown to the submarine force. Before the war, experiments had attempted simultaneous attacks by several submarines, but communications between boats were not good enough to ensure safety in peacetime operations. These tactics were cursorily explored late in 1941 but were abandoned due to fears of blue-on-blue incidents and limited communications capabilities.33

Now, however, conditions were different, radar had been perfected, high-frequency radio phones were installed, and communications were vastly improved.34 Coordination could be achieved, but the American submariners had little practice at it. The submarine force would have to investigate new tactics on the fly in the midst of the war. (Somewhat ironically, King called for emulating German submarine tactics just as that force was passing the apex of its operational effectiveness. May 1943 was considered the blackest month for the U-boats in the cruel Battle of the Atlantic.35)

King’s message eliminated debate, but the Pacific submarine fleet took its time to interpret fully the doctrinal and tactical implications of the new approach. As a result, the U.S. Navy did not employ the same approach as the Germans. U-boat wolf packs in the Kriegsmarine were ad hoc and fluid. When Admiral Karl Dönitz received intelligence about the location and character of a convoy, he would direct a number of boats to converge on an area where he expected the convoy to be. He would thus direct the assembly of the wolf pack and coordinate its attack from long distance. There was no on-scene commander or collective attack.36 The U-boats were simply sharks, swarming and attacking at will, or swarming to designated areas when directed. The Atlantic convoys were rather large (30 or more ships), encompassing a relatively wide area. A convergence could bring together as many as a dozen boats swarming around a big convoy but without any on-scene battle management.37 A single U-boat would be easily driven off, but a pack would not be. They would stalk the merchant shipping and pick off the slowest quarry every time.

King’s intervention about collective action proved timely. The Japanese navy did eventually enhance its ASW efforts, employing land-based surveillance, better radars, and more coordination. As the U.S. boats were drawing closer to Japan’s home islands, their targets were hugging closer to shallow waters and staying within air coverage. This raised the risk that American submarines would be identified and attacked.

Concerted action by the submarines could offset these changes in the operating context. Singular attacks would draw all the attention of an escort, ensuring that the U.S. boats were driven deep and away from their wounded targets. Coordination by multiple boats would allow continuous pressure on a Japanese shipping convoy and increase the strangulation that Lockwood was aiming to achieve. Multiple threats would distract the convoy’s protective screen and generate more opportunities out of each convoy that was found.

The U.S. Navy did not embrace German wolf pack doctrine or terminology; the accepted term for the tactic was coordinated attack group (CAG). An innovative submariner, Captain Charles “Swede” Momsen, developed the tactics and commanded the initial U.S. wolf pack in the early fall of 1943.38 American CAGs would initially have a senior commander on scene, but it would not be one of the boat’s skippers, as Lockwood desired to have his older division commanders get wartime experience on boats.39

The investigative phase was exhaustive and deliberate over several months. Experienced submarine commanders, not staff officers, developed the required tactics and communication techniques. In an echo of prewar Newport, discussions evolved into small war games on the floor of a converted hotel, which conveniently had a chessboard floor of black and white tiles. The officers who would conduct these patrols developed their own doctrine and tactics.40 The staff and prospective boat captains tested various ways both to scout for targets and then to assemble into a fighting force once a convoy was detected. War games, drills, and ultimately at-sea trials were conducted to refine a formal doctrine. Momsen drilled his captains in tactics, planning to have three boats attack successively—one boat making the first attack on a convoy, then acting as a trailer while the other two attacked alternately on either flank. He also developed a simple code for use on the new “Talk Between Ships” system so that boats could communicate with each other without being detected or intercepted by the Japanese.

The American approach rejected the rigid, centralized theater command and ad hoc tactical structure of the Germans.41 Consistent with its culture, the U.S. Navy took the opposite approach. CAGs comprised three to four boats under a common tactical commander who was present on scene. Unlike the Germans, these attack groups trained and deployed together as a distinctive element. They patrolled in a designated area under a senior commander and followed a generic attack plan. Other than intelligence regarding potential target convoys, orders came from the senior tactical commander on scene and not from the fleet commander. This tactical doctrine called for successive rather than swarming attacks.42 Subsequently scholars have been critical of these deliberate and sequential attack tactics, which negated surprise and simplified the job of Japanese escorts.43

Strangely, there seems to have been little urgency behind COMSUBPAC’s doctrinal and organizational adaptation. This top-down direction from afar (from Admiral King) appears to have been resisted until met with bottom-up evidence derived from experienced skippers. In the records of this period, Lockwood appears to be guilty of delaying tactics, but captains John “Babe” Brown and Swede Momsen convinced him to have “a change of heart.”44

Lockwood and his team at Submarine Force Pacific did not merely take King’s directive and implement it. He and the commander of U.S. submarines based in Australia, Rear Admiral Ralph Christie, were not in favor of the change in tactics. In his memoirs, Lockwood noted in a single sentence that he was directed to conduct wolf pack tactics by King. He did apply groups of four to six boats in his packs. And while he did develop the doctrine King tasked them to create, he did not apply it as King desired, against military shipping or approaches to critical operational areas. Instead, Lockwood deployed the CAGs to his ruthless campaign of attrition against Japanese commerce. The developmental process was entirely consistent with bottom-up adaptation. Lockwood was permitted to develop the command and control process, tactics, and training program on his own. Centralized command from Pearl Harbor was rejected, which reflected both the traditional Navy culture of command responsibility and autonomy and Lockwood’s appreciation for how Allied direction finding and signals intelligence in the Atlantic were fed by Dönitz’s centralized control and extensive communications.

Even after his change of heart, Lockwood and the submarine force took their time to work out the required doctrine and tactics in an intensive investigatory phase. The first attack group, comprised of the Cero (SS-225), Shad (SS-235), and Grayback (SS-208), was not formed until the summer of 1943. Momsen, who had never been on a combat patrol, was the commodore and rode in Cero. The pack finished its preparations and deployed from Pearl Harbor in late September on its combat patrol from Midway on October 1, 1943, exactly 6 months to the day from King’s message. This was hardly rapid adaptation, given the lessons from both the German success story in the Atlantic and the lack of success in the Pacific.

The initial cruise was deemed a success. Momsen’s CAG arrived in the East China Sea on October 6, 1943. It made a single collective attack on a convoy and was credited with sinking five Japanese ships for 88,000 tons and damaging eight more with a gross tonnage of 63,000 tons. While this met the measures of success that Lockwood wanted, the commanders involved were less than enthusiastic. The comments from the participating captains were generally mixed, with many indicating they would prefer to hunt alone rather than as a member of a group. They believed that the problems of communication were technologically unsolvable and that the risk of fratricide was unavoidable. Moreover, commanders preferred operating and attacking alone—consistent with the Navy’s traditional culture and the community’s enduring preference for independent action (and the rewards that came with it). Momsen, perhaps reflecting an appreciation of the complementing role high-level intelligence could play, recommended centralized command from Pearl Harbor rather than an on-the-scene commander, something Lockwood immediately overruled.45 But various packs were planned and began training. Ingrained conservatism and fear of firing on a friendly vessel framed the emerging tactics. These in practice emphasized “cooperative search” over collective attack.46

The need to explore innovative tactics was directed from the top, but the Navy leadership was patient in letting local leaders figure out the “how.” The validity of coordinated action grew on commanders such as Lockwood. Whatever reservations they might have held, the American wolf packs continued during the remainder of the year and were a common tactic during 1944. Unlike Dönitz’s Operation Paukenschlag (Drumbeat) in the Atlantic in early 1943, Lockwood’s force began to win the war of attrition in the Pacific. The success was likely due to the combination of finally having defect-free torpedoes and employing new search tactics. But as Lockwood noted in a tactical bulletin, for the first time, tonnage totals between the German effort and that of the American submarine force “now compare favorably.”47

One dramatic case gives an example of how effective CAGs could be. In late July 1944, Commander Lawson “Red” Ramage commanded the USS Parche, part of a wolf pack labeled “Park’s Pirates” after Captain Lew Parks, also aboard the Parche. The Pirates included the USS Steelhead, skippered by Lieutenant Commander Dave Whechel, and the USS Hammerhead, whose skipper was Commander Jack Martin. After a patch of bad weather and poor radio reporting, the Pirates found their quarry. Although frustrated by miscommunications, Martin identified a large Japanese convoy on the evening of July 30. Although it was a long shot, Parks ordered Ramage to give chase, and for 8 hours the Parche chased down the fleeing convoy.

What happened next was a maritime melee. Ramage surfaced inside the convoy in the dark and began a methodical attack, slicing in and around the larger tankers and setting up shots that ranged from only 500 to 800 yards. Ramage’s boat passed within 50 feet of one Japanese corvette on an opposite tack that could not depress its guns enough to strike it.48 The Parche was almost rammed once and was subjected to fire from numerous vessels as it raised havoc with the 17 merchant ships and 6 escorts of Convoy MI-11.

Within 34 minutes, Ramage fired 19 torpedoes and got at least 14 hits. Lockwood credited Parche with 4 ships sunk and 34,000 tons, while the Steelhead got credit for 2 ships of 14,000 tons. Ramage’s epic night surface attack earned him the Medal of Honor.49 His daring rampage was a perfect example of a loosely coordinated attack relying on individual initiative (not unlike a classic U-boat commander’s approach in its execution) rather than formal tactics or a set piece approach that failed to overwhelm the escorts.50

After mid-1944, there were no major adaptations in submarine warfare during the remainder of the Pacific campaign. Ships, doctrine, training, and weapons were highly effective. In a sense, the U.S. submarine war did not truly begin until the CAGs went to sea in late 1943. Until then, it “had been a learning period, a time of testing, of weeding out, of fixing defects in weapons, strategy, and tactics, of waiting for sufficient numbers of submarines and workable torpedoes.”51 Yet within a few months, Japan’s economic lifeline was in tatters.

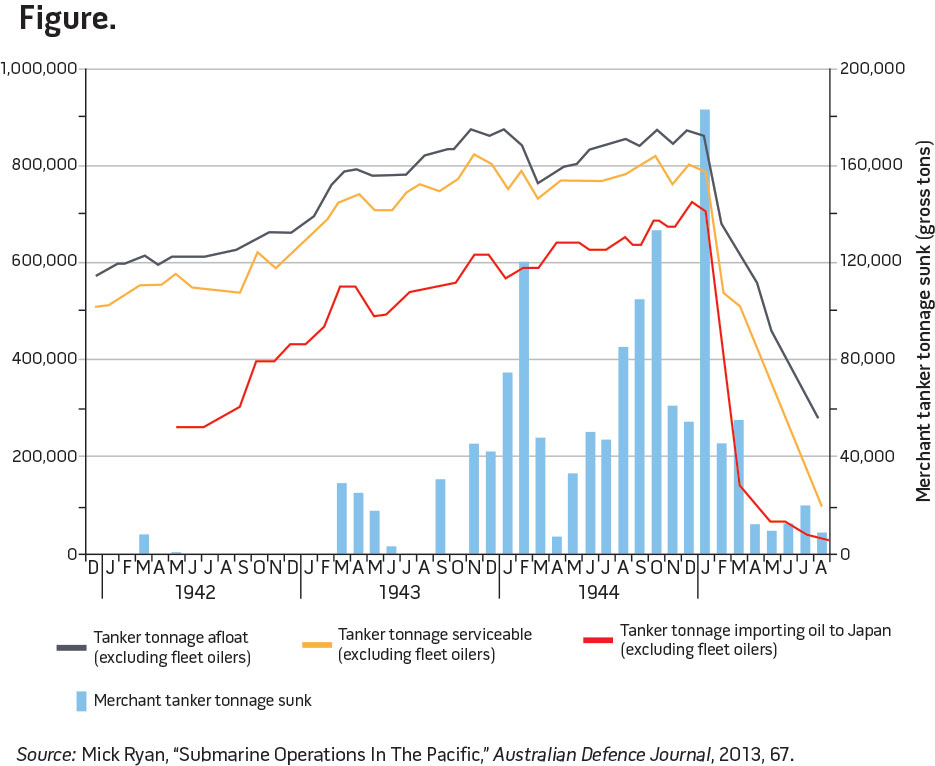

Exploiting an increased number of boats and the shorter patrol distances afforded by advanced bases in Guam and Saipan, U.S. patrol numbers increased by 50 percent to 520 patrols in 1944. These patrols fired over 6,000 torpedoes, which had become both functional and plentiful. They sank over 600 ships for nearly 3 million tons of shipping. They reduced Japan’s critical imports by 36 percent and cut the merchant fleet in half (from 4.1 million to 2 million tons). While Japanese oil tanker production increased, oil imports dropped severely (see figure).52

Lockwood took wolf packs to a new level in 1945. Now a firmly convinced advocate, he carefully planned an operation with nine boats, operating in three wolf packs, that would traverse the heavily mined entrances of the Sea of Japan.53 The development of an early version of mine-detecting FM sonar allowed boats to detect mines at 700 yards and bypass them. Submarines could now enter mined waters such as the Straits of Tsushima surreptitiously and operate in areas the Japanese mistakenly believed were secure, cutting off the crucial foodstuffs and coal shipments transiting from Korea to Japan. Lockwood’s staff meticulously planned this operation, partially motivated by his desire to avenge the loss of the heroic Commander Dudley Morton and the USS Wahoo in the northern Sea of Japan in fall 1943. Each of the U.S. boats was fitted with FM sonar, and the crews received detailed training in its use. Once they had made the passage and were at their assigned stations in the Sea of Japan, the submarines, working in groups of three, were scheduled to begin a timed attack throughout the area of operations at sunset on June 9. This collective action group was unique in that, instead of gaining an advantage by concentrating their combat power on a single target or convoy, the Hellcats concentrated as a group for their entrance through the narrow Tsushima and then disaggregated. Their simultaneous but distributed attack was designed to shock the Japanese and overwhelm their ability to respond.

In Operation Barney, nine boats led by Captain Earl Hydeman successfully surprised the Japanese and sank 27 vessels in their backyard.54 But it cost Lockwood one of his own boats, as the USS Bonefish under Lieutenant Commander Lawrence Edge was lost with all hands.55

Without King’s top-down intervention, the adaptation to the use of CAGs may not have been initiated. The success of its adoption, however, was a function of letting local commanders develop their own doctrine. By the end of the war, Lockwood was more enthusiastic about the prospects of the American wolf packs. A total of 65 different wolf packs deployed from Hawaii, and additional groups patrolled out of Australia as well.56 Ironically, they never focused on King’s original intent of serving as ambushers against naval combatants. Instead, the packs remained true to Lockwood’s guerre de course against Japan’s economy.

Cross-Domain Synergies

The historical requirement to adapt in the future may be complicated by the evolving character of modern conflict and the expectation that the joint force will need to gain and exploit cross-domain synergies. The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Capstone Concept for Joint Operations (CCJO) is predicated upon creating cross-domain synergies to overcome operational challenges. Another element is to seize, retain, and exploit the initiative in time and across domains.57 Some of this synergy will no doubt be gained in peacetime through concerted efforts to improve interoperability. But if cross-domain synergy is to “become a core operating concept,” as suggested by former Chairman General Martin Dempsey (Ret.) in the CCJO, then we need to also expect to seek out new synergies in wartime.58 Here again, the submarine case study—with its numerous technological adaptations (surface and air search radars, sonars, and improved torpedoes) and cooperation with signals intelligence and the Army Air Corps—is evidence that trans-domain learning is both necessary and feasible, even in combat conditions.

This raises a set of critical questions about joint adaptation in tomorrow’s wars. In future conflicts, how prepared will the joint community be to establish test units and create synergistic combinations on the fly? How prepared are we to actively adapt “under fire” as a joint warfighting community? Do we have the right learning mechanisms to create, harvest, and exploit lessons horizontally across the joint force during combat operations? Such horizontal learning has been crucial in successful examples of adaptation in the past.59 Based on this case study, and several others conducted in a formal case study of U.S. military operations, the following recommendations are offered.

Leadership Development. Senior officers should understand how enhanced operational performance is tied to collaborative and open command climates in which junior commanders can be creative, and plans and tactics can be challenged or altered. The importance of mission command should not excuse commanders from oversight or learning, from providing support, or from recognizing good or bad practices for absorption into praxis by other units. Professional military education (PME) programs should develop and promote leaders who remain flexible, question existing paradigms, and can work within teams of diverse backgrounds to generate collaboration and greater creativity. Case studies in military adaptation should be part of PME strategic leadership syllabi.

Cultural Flexibility over Doctrinal Compliance. Joint force commanders should instill cultures and command climates that embrace collaborative and creative problem-solving and display a tolerance for free or critical thinking. Cultures that are controlling or doctrinally dogmatic or that reinforce conformity should not be expected to be adaptive. Commanders should learn how to create climates in which ideas and the advocates of new ideas are stimulated rather than simply tolerated. If institutions are to be successful over the long haul or adaptive in adverse circumstances, promoting imaginative thinking and adaptation is a must.

Learning Mechanisms. Commanders should be prepared to use operations assessments to allow themselves to interpret the many signals and forms of feedback that occur in combat situations. If needed, they may elect to create special action teams or exploit formalized learning teams to identify, capture, and harvest examples of successful adaptation. These teams or units might have to be created to experiment with new tactics or technologies. Commanders should codify a standard process to collect lessons from current operations for rapid horizontal sharing. They have to be prepared to translate insights laterally into modified praxis to operational forces and not just institutionalize these lessons for future campaigns via postconflict changes in doctrine, organization, or education.

Chief Torpedo man Donald E. Walters receives Bronze Star for service aboard USS Parche (SS-384) (U.S. Navy/Darryl L. Baker)

Dissemination. Commanders should invest time in ensuring that lessons and best practices are shared widely and horizontally in real time to enhance performance and are not just loaded into formal information systems. The Israel Defense Forces are exploring practices that make commanders more conscious about recognizing changes in the operating environment from either their own forces or the opponent.60 There may be something to practicing learning in this way and making it the responsibility of a commander instead of a special staff officer.

Conclusion

As Ovid suggested long ago, one can learn from one’s enemies. The U.S. Navy certainly did. The Service did not just emulate the Kriegsmarine; it improved upon its doctrine with tailored tactics and better command and control capabilities. To do so, Navy submarine leaders had to hold some of their own mental models in suspended animation and experiment in theater with alternative concepts. Lessons were not simply harvested from existing patrols and combat experience and plugged into a Joint Universal Lessons Learned System, as is done today. The submarine force had to carve out the resources, staff, and time to investigate new methods in a holistic way from concept to war games to training against live ships.

Because the eventual role of the Silent Service was not anticipated with great foresight, the Americans had to learn while fighting. They accomplished this with great effectiveness, learning and adapting their tactics, training, and techniques. But the ultimate victory was not due entirely to the strategic planning of War Plan Orange. Some success must be credited to the adaptation of the intrepid submarine community.

Ultimately, the U.S. Navy’s superior organizational learning capacity, while at times painfully slow, was brought to bear. The Navy dominated the seas by the end of World War II, and there is much credit to assign to the strategies developed and tested at the Naval War College and the Fleet Exercises of the interwar era. However, a nod must also be given to the Navy’s learning culture of the submarine force during the war. The Service’s wartime “organizational learning dominance” was as critical as the foresight in the interwar period.61 To meet future demands successfully, the ability of our joint force to rapidly create new knowledge and disseminate changes in tactics, doctrine, and hardware will face the same test. JFQ

Notes

1 Theo Farrell, Military Adaptation in Afghanistan, ed. Theo Farrell, Frans Osinga, and James Russell (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2012), 18.

2 Joint and Coalition Operational Analysis, Decade of War: Enduring Lessons from the Past Decade of Operations, vol. 1 (Suffolk, VA: The Joint Staff, June 15, 2012).

3 A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, March 2015), 31.

4 For a good overview, see Anthony Newpower, Iron Men and Tin Fish: The Race to Build a Better Torpedo During World War II (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2006).

5 Theodore Roscoe, United States Submarine Operations in World War II (Annapolis, MD: U.S. Naval Institute, 1949), 479.

6 Wilfred Jay Holmes, Undersea Victory: The Influence of Submarine Operations on the War in the Pacific (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1966), 351.

7 James M. Scott, “America’s Undersea War on Shipping,” Naval History, December 2014, 18–26.

8 Ian W. Toll, Pacific Crucible: War at Sea in the Pacific, 1941–1942 (New York: Norton, 2012), xxxiv.

9 Roscoe, 18.

10 Joel Ira Holwitt, “Unrestricted Submarine Victory: The U.S. Submarine Campaign against Japan,” in Commerce Raiding: Historical Case Studies, 1755–2009, ed. Bruce A. Elleman and S.C.M. Paine (Newport, RI: Naval War College Press, October 2013).

11 Albert A. Nofi, To Train the Fleet for War: The U.S. Navy Fleet Problems, 1923–1940 (Newport, RI: Naval War College Press, 2010).

12 Michael Vlahos, “Wargaming, an Enforcer of Strategic Realism,” Naval War College Review (March–April 1986), 7.

13 Nofi, 271.

14 Craig C. Felker, Testing American Sea Power: U.S. Navy Strategic Exercises, 1923–1940 (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2007), 6.

15 Stephen Peter Rosen, Winning the Next War: Innovation and the Modern Military (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1994), 75.

16 Nofi, 307.

17 Holmes, 47.

18 Clay Blair, Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War Against Japan (New York: Lippincott, 1975), 41; Ronald H. Spector, Eagle Against the Sun: The American War with Japan (New York: Free Press, 1985), 484.

19 Charles A. Lockwood, Sink ’Em All: Submarine Warfare in the Pacific (New York: Dutton, 1951), 52.

20 I.J. Galantin, Take Her Deep! A Submarine Against Japan in World War II (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2007), 18.

21 Roscoe, 57.

22 Felker, 62.

23 See J.E. Talbott, “Weapons Development, War Planning, and Policy: The U.S. Navy and the Submarine, 1917–1941,” Naval War College Review (May–June 1984), 53–71; Spector, 54–68, 478–480.

24 Joel Ira Holwitt, “Execute Against Japan”: Freedom-of-the-Seas, the U.S. Navy, Fleet Submarines, and the U.S. Decision to Conduct Unrestricted Warfare, 1919–1941 (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2009), 479.

25 Blair, Silent Victory, 334–345.

26 Lockwood, Sink ’Em All, 27.

27 Steven Trent Smith, Wolf Pack: The American Submarine Strategy That Helped Defeat Japan (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley, 2003), 50; Lockwood, Sink ’Em All, 87.

28 Smith, 51.

29 Ibid.

30 Galantin, 126.

31 Library of Congress, Lockwood Papers, box 12, folder 63, letter, Lockwood to Admiral Leary, July 11, 1942.

32 National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), RG 313/A16 3 (1), Commander, Submarine Forces Pacific, Tactical Bulletin #1-43, January 2, 1943.

33 Roscoe, 240.

34 Charles A. Lockwood and Hans Christian Adamson, Hellcats of the Sea (New York: Bantam, 1988), 88.

35 Peter Padfield, War Beneath the Sea: Submarine Conflict During World War II (New York: Wiley & Sons, 1995), 308–336; Michael Gannon, Black May: The Epic Story of the Allies’ Defeat of the German U-boats in May 1943 (New York: HarperCollins, 1998).

36 Blair, Silent Victory, 360.

37 Clay Blair, The Hunters, 1939–1942 (New York: Random House, 1998); Michael Gannon, Operation Drumbeat, The Dramatic True Story of Germany’s First U-Boat Attacks Along the American Coast in World War II (New York: Harper & Row, 1990), 89–90.

38 Blair, Silent Victory, 511–516; Roscoe, 240.

39 Library of Congress, Lockwood Papers, box 13, folder 69, letter, Lockwood to Nimitz, May 4, 1943.

40 Galantin, 124–129.

41 Padfield, 85–130.

42 Galantin, 129.

43 Padfield, 404–405.

44 Blair, Silent Victory, 479–480.

45 Roscoe, 241.

46 Ibid., 341.

47 NARA, RG 38, Naval Command Files, box 357, Commander, Submarine Forces Pacific, Tactical Bulletin #6-43, November 22, 1943.

48 Stephen L. Moore, Battle Surface: Lawson “Red” Ramage and the War Patrols of the USS Parche (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2011), 116.

49 Ibid., 110–116.

50 Padfield, 433. On the engagement, see Moore, 101–118. See also War Patrol Report #2, August 1944, available at <http://issuu.com/hnsa/docs/ss-384_parche>.

51 Blair, Silent Victory, 524.

52 Ibid., 791–793; Roscoe, 432–433.

53 The operation is covered in detail in Peter Sasgen, Hellcats: The Epic Story of World War II’s Most Daring Submarine Raid (New York: Caliber, 2010).

54 Holmes, 459–461.

55 NARA, RG 38, Naval Command Files, box 358, “Operation Barney” in Submarine Bulletin II, no. 3 (September 1945), 10–16.

56 See the list at <www.valoratsea.com/wolfpacks.htm>.

57 “Chairman Releases Plan to Build Joint Force 2020,” new release, September 28, 2012, available at <www.defense.gov/news/newsarticle.aspx?id=118043>.

58 Cross-domain synergy is a key concept in joint concepts such as the Joint Operational Access Concept and the Chairman’s Concept for Joint Operations. See Capstone Concept for Joint Operations, Joint Force 2020 (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, September 10, 2012), 13.

59 Robert T. Foley, “A Case Study in Horizontal Military Innovation: The German Army, 1916–1918,” Journal of Strategic Studies 35, no. 6 (December 2012), 799–827.

60 Raphael D. Marcus, “Military Innovation and Tactical Adaptation in the Israel-Hizbollah Conflict: The Institutionalization of Lesson-Learning in the IDF,” Journal of Strategic Studies 38, no. 4 (2014), 1–29.

61 R. Evan Ellis, “Organizational Learning Dominance,” Comparative Strategy 18, no. 2 (Summer 1999), 191–202.