DOWNLOAD PDF

Dr. Thomas R. Cullison is Senior Advisor to the Center for Disaster and Humanitarian Assistance

Medicine at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences. Dr. Charles W. Beadling

is Director of the Center for Disaster and Humanitarian Assistance Medicine. Lieutenant Colonel

Elizabeth Erickson, USAF, is Chief of Strategic Health Engagement Operations in the Surgeon’s Office at

Headquarters, U.S. Pacific Command, Camp Smith, Hawaii.

In his February 2014 testimony to the House Armed Services Committee, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs Jonathan Woodson articulated six strategic lines of effort supporting then–Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel’s “six strategic priorities for reshaping our forces and institutions for a different future.” Dr. Woodson’s sixth line of effort was to “expand our global health engagement strategy.” This article is an overview of U.S. global health engagement, including such topics as current guidelines, health as a strategic enabler, health in disaster management, and future directions for global health engagement.

U.S. Army medical doctor with Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center at Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency excavation site searches for remains of five MIAs lost in B-24 crash from World War II, located near Riechelsdorf, Germany, September 1, 2015 (DOD/U.S. Air Force/Brian Kimball)

Why Military Global Health Engagement?

President Theodore Roosevelt’s foreign policy has been summarized as “speak softly and carry a big stick.” This has evolved over time into “smart power,”1 a combination of “hard power” and “soft power” as outlined in the first Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review.2 Many observers see topics, including health, that simultaneously benefit a population while advancing U.S. interests as legitimate areas for international engagement. Others view such activities as inappropriate for foreign militaries, believing all actors in the humanitarian space should behave apolitically, strictly following the humanitarian principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality, and independence, particularly during disaster response. In their extensive review of U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) health engagement, Josh Michaud and his coauthors note the concern voiced by many other governmental and nongovernmental humanitarian actors regarding military participation in this arena:

This has led to some ambiguity and tension regarding the role of DOD in [health engagement], with many in the global health community having reservations about DOD’s efforts but lacking a full understanding of its work, and DOD at times failing to give due consideration to the methods and principles that define successful global health programs even as it has increased its attention to such activities.3

Guidelines for foreign military and civil defense organizations have been developed to address these concerns and discussions continue to resolve differences,4 yet much work remains.

Numerous senior officials concur that health is an effective, ethical platform for engaging partner nations, both in a security cooperation capacity and as part of disaster response.5 Wisely executed, U.S. DOD global health engagement (GHE), coupled with U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) development efforts and State Department diplomacy, can both advance our national security strategy and benefit health throughout the world.

Current Alignment Guidelines

Within DOD, strategic policy on health engagement is generated by the Office of the Secretary of Defense for Policy’s Office of Stability and Humanitarian Affairs, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs, and Joint Staff Surgeon. Coordination and input are sought from the Departments of Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, Agriculture, and Energy, among others. Two DOD instructions (DODI), both developed in the context of recent activities in Iraq and Afghanistan, are widely considered GHE source documents: DODI 3000.05, “Stability Operations,” and DODI 6000.16, “Health Support for Stability Operations.” A 2013 Secretary of Defense cable, “Guidance for DoD Global Health Engagement,” codifies responsibility, scope, and funding for GHE carried out by DOD organizations.5 While this document makes great strides in defining and aligning GHE activities, more granular direction addressing personnel requirements, monitoring and evaluation, and research in this area is expected in the near future.

Health as a Strategic Enabler

Over the past decade, DOD health activities have gained increased visibility as tools for advancing U.S. national interests. The basic notion of enhancing strategic interests through relationship-building has always been made clear. Examples include annual U.S. Navy hospital ship deployments such as Pacific Partnership and Continuing Promise, and U.S. Air Force Operation Pacific Angel missions. In recent years, a significant shift has occurred within DOD health engagements from predominantly direct provision of care activities (often known as medical civic action programs) to more engagements focused on building partner nation capacity. GHE programs range from assisting a developing nation to improve its population’s health through infrastructure improvement and educational opportunities, to developing military health interoperability with a medically sophisticated ally with whom the United States may regularly deploy in contingencies. Successful DOD health engagement planning considers political, social, educational, and economic factors within a country; how the host nation’s population views its military; and regional relationships that may encourage or dissuade multilateral engagements. Thoughtful use of health engagements as a theater security cooperation tool has paved the way for broader security cooperation in many nations.

In recent years, relationships have dramatically improved between military medical organizations, other U.S. Government agencies, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) involved in global health activities. For example, medical staff members representing numerous civilian NGOs and universities routinely deploy with U.S. Navy hospital ship missions. Military liaison officers are assigned to the USAID Office of Civilian-Military Cooperation to coordinate overseas development and defense activities, and USAID representatives work in geographic combatant commander headquarters coordinating military theater security cooperation events with USAID development programs in the respective regions. An integrated whole-of-government approach to health security concerns supports achievement of national security goals.

Health Engagement in Geographic Combatant Commander Area of Responsibility

Operationally, geographic combatant commanders guide GHE efforts to support U.S. interests in their areas of operation through theater security cooperation plans, which are part of larger theater campaign plans. Appreciation of GHE as a security cooperation capability varies somewhat among the commanders. Within U.S. Pacific Command (USPACOM), for example, health engagement is seen as a key enabler for full-spectrum theater security cooperation. The USPACOM surgeon prepares a Health Theater Security Cooperation Plan, which provides general health engagement guidance, emphasizing principles such as focusing engagements on building capacity, capability, and interoperability; planning engagements that are sustainable and reciprocal; coordinating with other organizations working in the global health arena; and using direct patient care if it is the only means to achieve the engagement objectives. The plan also prioritizes health lines of effort and functional areas for each country, aligning efforts to reach theater campaign plan objectives. Health engagement events are integrated within country security cooperation plans, which security cooperation officers develop with the interagency U.S. country team in keeping host nation priorities.

Health engagement activities involve a number of DOD health organizations, including Service components and subordinate units, National Guard State Partnership Programs, Army and Navy overseas research laboratories, and educational institutions such as the U.S. Air Force School of Aerospace Medicine, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS), and Defense Institute of Medical Operations. GHE activities may occur within scheduled military exercises (such as Cobra Gold or Balikatan in USPACOM); within humanitarian assistance/disaster response–focused engagements (such as Continuing Promise and New Horizons in U.S. Southern Command); as a series of subject matter expert exchanges; within peacekeeping operations training; or within multilateral structures such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations Defense Ministers Meeting–Plus Expert Working Group on Military Medicine. Additionally, foreign military medical personnel attend short- and long-term training courses in the United States, which results in strong relationships and paves the way for increased military health interoperability.

Regularly scheduled academic programs and subject matter expert exchanges are extremely important. Recently, the USUHS Center for Disaster and Humanitarian Assistance Medicine (CDHAM) has partnered with geographic combatant commanders on regional health strategy symposia. These engagements bring together senior and mid-level health leaders from DOD health organizations, partner nations, the U.S. Government interagency community, and the broader global health community to focus on the nexus between health and security. These events have increased awareness of and skills in GHE for DOD members, built interagency and whole-of-society relationships, and explored complex issues of health and security. In U.S. Central Command, this concept has been applied in a regional setting with participants from partner nations, and plans are in place to expand this model to USPACOM and other commands. Growing global threats from infectious diseases that know no national borders necessitate collaboration, cooperation, and information-sharing, which academic programs promote.

Following the Ebola crisis in West Africa, U.S. Africa Command established the African Partner Outbreak Response Alliance. Using the U.S. Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center and CDHAM as implementing partners, the alliance is designed to improve African militaries’ ability to effectively support civilian authorities to identify and respond to a disease outbreak.

Focus Areas

DOD health activities span a wide range of engagement types and topics. We suggest the following general principles and focus areas for DOD global health engagement as the most effective.

Continue Military-to-Military Engagement on Health Issues Unique to Uniformed Armed Forces. U.S. military health capabilities are unmatched by those of any other nation’s armed forces. We excel in many fields: industrial hygiene, preventive medicine, infectious disease, and combat trauma, to mention a few. We are world leaders in military-specific areas such as combat stress, aerospace medicine, aeromedical evacuation, undersea medicine, and field medicine. We have much to learn from our colleagues in other nations, however, particularly about region-specific diseases, practices, and successes. Subject matter expert exchanges should be just that: bi-directional exchanges of knowledge and experience. These exchanges, whether during planned military exercises, international officer exchanges, educational programs, or medical conferences, result in expanded cultural understanding, increased medical competency of all participants, and improved interoperability between military medical services.

Leverage Existing Capabilities. The U.S. military health system possesses unique assets that regularly provide services of worldwide importance yet are little known beyond their narrow sphere. DOD overseas medical research laboratories have provided fundamental research supporting force health protection against infectious diseases throughout the world for over half a century. Working alongside host nation military and ministry of health scientists and technicians, these laboratories have strengthened both health systems and U.S. relationships with partner nations.6 Collaboration among uniformed U.S. public health and tropical disease specialists and their civilian colleagues in numerous nations has resulted in enduring professional relationships and personal friendships.

Contribute to Established International and U.S. Government Health Programs. Military medical research initially performed to protect troops in combat served as the foundation for public health efforts throughout the world. To remain relevant, today’s U.S. military health engagement programs must be synergistic with ongoing civilian-sector programs carried out by international organizations, national development agencies, NGOs, and other actors in the global health space.

In 2000, world leaders established time-bound targets, the Millennium Development Goals, to focus efforts in eight specific areas, three of which are directly related to health.7 Goal 6 commits to “combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases” with specific targets to “have halted by 2015 and begun to reverse the spread of HIV/AIDS” and “have halted by 2015 and begun to reverse the spread of malaria and other diseases (particularly tuberculosis).” Specific indicators have been established to track progress on each of these endeavors.

Concerns regarding the impact of rapidly spreading infectious disease on freedom of movement and the world economy led to the 2005 World Health Organization (WHO) International Health Regulations, committing all signatory nations to high standards of disease surveillance and reporting. Realizing that not all could reach these goals, the United States launched the Global Health Security Agenda in 2014 in partnership with the WHO and 47 other countries (to date), providing assistance in developing a worldwide network to “prevent, detect, and respond” to infectious diseases threats. The longstanding relationships, infrastructure, and interagency goodwill developed, particularly through the overseas infectious disease research laboratories and Defense HIV/AIDS Prevention Program, have been instrumental in all aspects of GHE.

Focus on Trauma Care. Throughout history, advances in military trauma care have been applied to civilian settings. The recent unparalleled U.S. success in decreasing combat deaths resulted from continually applying basic science and systems research to an already excellent military trauma system extending halfway around the world. Although many surgical techniques have been refined, much of the success is due to previously unstudied logistic, transportation, and environmental factors. The expressed interest in trauma care from numerous partner nations, the overlap between civilian and military applications, and the applicability in disaster response suggest that trauma should be a mainstay topic for GHE programs.

Health in Disaster Management

An inherent responsibility of any government is to protect its citizens from harm, including the ravages of disasters. Disaster resilience depends upon all societal components functioning synergistically, particularly the society’s health system—both the hygiene and preventive services inherent in a strong public health system and the ready access to effective clinical capabilities necessary to successfully treat disease and injury.

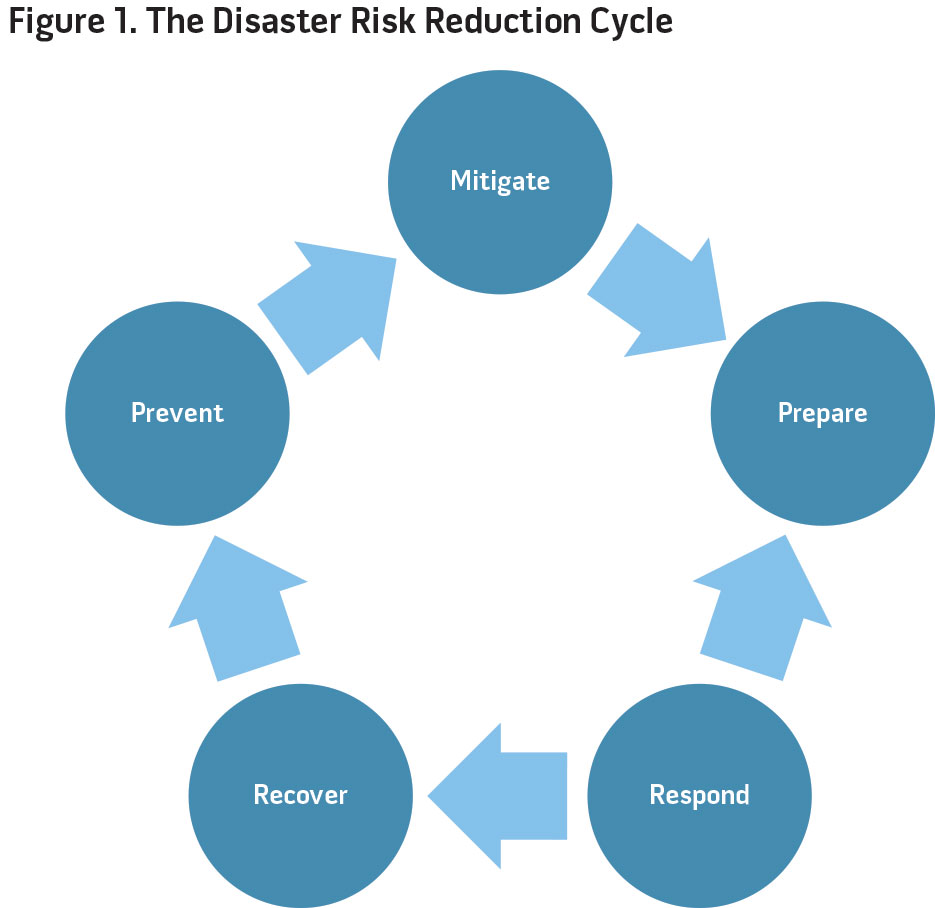

Properly executed disaster management is a continual process of improvement activity illustrated in the Disaster Risk Reduction Cycle (see figure). This framework involves anticipating likely occurrences, responding when they occur, cleaning up and rebuilding during the recovery phase, and then studying the event to achieve a better outcome the next time. Wide media attention focuses on tragic and heroic events during the immediate response phase, but forward thinking and planning during the prevention, mitigation, and preparation phases save more lives and usually go unnoticed. Certain natural phenomena, such as seismic activity or precipitation, cannot be prevented, and therefore mitigation—earthquake-resistant building codes, for example—is important to reduce an event’s impact. For some threats, such as industrial accidents or infectious disease, prevention is especially important.

During the 2010 Haitian earthquake and 2011 Japanese tsunami, worldwide attention was riveted to compelling images of devastated towns, disrupted public services, and heart-rending human suffering. As conditions stabilized and no further immediate devastation seemed imminent, attention focused on other events.

In December 2004, a massive tsunami caused widespread loss of life and destruction throughout the eastern Indian Ocean region. The Indonesian province of Aceh on the island of Sumatra sustained particularly horrific damage, resulting in hundreds of thousands of lives lost and entire villages obliterated. The immense U.S. response initially centered on the USS Abraham Lincoln battle group that was relieved by the hospital ship USNS Mercy approximately 30 days after the event. Public opinion polls showed a marked increase in positive views of Indonesians toward the United States, at least in the short term, as a direct result of this disaster assistance.

Many individuals and organizations expressed concern that foreign military involvement in disaster response would be used for immediate geopolitical advantage. From 1992 to 1994, a United Nations (UN)-sponsored international committee developed the Guidelines on the Use of Foreign Military and Civil Defence Assets in Disaster Relief. Known as the “Oslo Guidelines,” they stated in part: “Foreign military and civil defence assets should be requested only where there is no comparable civilian alternative and only the use of military or civil defence assets can meet a critical humanitarian need. The military or civil defence asset must therefore be unique in capability and availability.”8 These guidelines, updated in 2007 following the unprecedented international military response to the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, discuss three levels of activity: direct assistance, indirect assistance, and infrastructure support. Foreign militaries are expected to operate in the background in support of host nation and international civilian relief operators, performing “indirect assistance” and “infrastructure support” unless no other capability is available to meet the need. During the U.S. response to the Haitian earthquake, over 13,000 U.S. military personnel were involved in all three levels of response. Direct assistance was provided in the form of medical and surgical care on board the hospital ship USNS Comfort until sufficient capability was available ashore. Indirect assistance involved flying patients to the ship by military aircraft. Infrastructure support included enabling logistic capabilities by restoring and operating the Port-au-Prince airport and port facilities.

The Oslo Guidelines require transfer of military relief functions to civilian authorities once the immediate requirement has been met. These often difficult transitions may be smoothed by establishing long-term working relationships between militaries and civilian disaster response organizations through conferences, combined study of previous events, and participation in each other’s exercises. Annual disaster relief, search and rescue, and medical interoperability exercises during normal times develop host nation capability while establishing expectations during actual crises. Using scenarios presenting likely events allows for critical analysis and preparation that will save lives.

Foreign military response to natural disasters will often deploy based on bilateral agreements or multilateral treaties. For example, U.S. military foreign humanitarian assistance normally supports the USAID Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance following a formal request for assistance by the host nation through the U.S. Ambassador and a request from the State Department for specific response capabilities. It is recommended that nations wishing to act bilaterally should make use of the Model Agreement set out in Annex I of the Oslo Guidelines.

Public health services and clinical care are occasionally the central focus of a disaster. Onset of the West African Ebola crisis was relatively gradual, with the number of cases increasing exponentially over a period of several months. This led to concern that the disease would spread to other regions including Europe, North America, and Asia. On August 8, 2014, the WHO Director-General declared the epidemic a “public health emergency of international concern.” Shortly thereafter, President Barack Obama stated Ebola is a “top national security priority for the United States” and committed significant assets to the effort. U.S. military activity was largely in the form of indirect and infrastructure support, including airlift establishing a regional intermediate staging base, constructing treatment facilities, training healthcare workers in personal protective procedures for safe patient interaction, and assisting with laboratory and surveillance techniques. In keeping with the Oslo Guidelines, uniformed U.S. Public Health Service providers, not military medical officers, provided direct care for healthcare workers who became ill while tending to others.

The above examples refer mainly to events occurring in the “respond” and early “recovery” phases of the disaster risk reduction cycle. Recovery, mitigation, and preparation activities are still occurring in all of these situations, including infrastructure replacement and rejuvenation.

“The time to exchange business cards is not during a disaster” is a common saying in disaster management. Much less visible but equally important is ongoing international disaster planning supported by U.S. agencies focused on whole-of-government capacity-building within low- and middle-income countries, assisting these nations to develop internal capability to decrease the impact, shorten the recovery period, and, most importantly, lessen human suffering. DOD entities involved in such work include the Center for Excellence in Disaster Management and Humanitarian Assistance, and the Center for Disaster and Humanitarian Assistance Medicine.

<img src="/Portals/68/Images/jfq/jfq-80/cullison-et-al-2.jpg" alt="Anesthesiologist examines child before her surgery aboard Military Sealift Command hospital ship USNS Comfort (T-AH 20) during Continuing Promise

2015, August 3, 2015 (U.S. Army/Lance Hartung)" width="100%" />

Anesthesiologist examines child before her surgery aboard Military Sealift Command hospital ship USNS Comfort (T-AH 20) during Continuing Promise

2015, August 3, 2015 (U.S. Army/Lance Hartung)

The U.S. Africa Command Disaster Preparedness Program (DPP) exemplifies a sustained engagement methodology for building disaster management capabilities and capacity. Since 2008, this effort has measurably enhanced disaster management of all hazards in over a dozen African partner nations. Additionally, several strategic benefits have been achieved, such as building strong relationships based on trust, improving cooperation between ministries within the countries, and creating a network of subject matter experts for collaboration across the continent. DPP promotes a whole-of-government effort throughout the entire disaster cycle, from prevention, mitigation, and preparedness to response and recovery. While the whole-of-government approach is essential to an effective disaster management program, the military-to-military aspect of DPP is emphasized. The Oslo Guidelines address the role of foreign military and civil defense but do not apply to a nation’s own military participation in domestic disaster response. The military is often a country’s most critical resource in effective disaster management.

In many nations, adequate contingency preparedness and response plans do not exist. The DPP process begins with a baseline analysis to identify disaster management capability and capacity gaps, which are prioritized in a strategic disaster management work plan. U.S. and host nation officials work together to create national disaster plans that are applied during a tabletop exercise for likely scenarios such as floods, earthquakes, or pandemic disease. In these sessions, technical experts are grouped not by agency or ministry but by function, representing command and control, logistics, health, communications, and security. Working together with civilian colleagues, often for the first time, participants develop important individual relationships as they form a national plan emphasizing military support to civilian authority, reinforcing integration of military and civilian government ministries and agencies throughout the sustained engagement process. DPP has assisted partners in writing 9 all-hazard contingency plans and 10 military pandemic preparedness and response plans. Each military pandemic plan aligns with that country’s national pandemic preparedness and response plan.

The emergence of a network of African disaster management experts, which has been effective for regional cooperation, is another powerful outcome. Key individuals with both the technical expertise and collaborative attitudes were identified and recruited as facilitators, turning bilateral into multilateral engagements. The benefit of this network was seen when representatives from two other West African countries responded to a Liberian request for assistance to advance national policy and legislation to improve disaster management capabilities. Although delayed for several months due to the Ebola epidemic, Liberia has since moved policy and legislation forward. Bringing these individuals together would have been unlikely without the relationships built through DPP over 7 years.

Future Directions

Military global health engagement is a valuable mechanism to simultaneously improve disaster preparation and response, increase population health around the world, and advance U.S. interests through all phases of the continuum of military operations, particularly in Phases 0 (shape) and 1 (deter).

In 2009, Eugene V. Bonventre and his colleagues published an excellent review of DOD GHE activities with several recommendations for interagency collaboration: creation of an overall global health security plan that combines civilian and military disease surveillance capabilities, and creation of a common interagency monitoring and evaluation capability to measure progress in health engagement activities.9 In 2014, J. Christopher Daniel and Kathleen H. Hicks noted steady progress in many of these areas, particularly interagency coordination, with regular meetings at the assistant secretary level, and an increase in liaison officers among DOD, USAID, and Health and Human Services.10 Certain structural reorganization—such as merging DOD bio-surveillance activities under the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center to better integrate with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and WHO worldwide disease surveillance—demonstrates progress in integrating with U.S. and foreign partners in areas of common interest.

Recommendations

Several significant issues must be addressed for global health engagement to become an accepted, routine military capability.

Clear doctrine must be developed for guiding DOD activities and for establishing effective coordination with other U.S. Government and international agencies with global health responsibilities.

Multiyear funding mechanisms must be developed to support sequential capacity-building efforts. GHE activities in general are funded with same-year dollars, inhibiting the establishment of ongoing activities required to develop strong health capabilities and meaningful research projects needed to establish strong relationships. The overseas laboratories and Defense HIV/AIDS Prevention Program are excellent examples of success through thoughtful budgeting, and leveraging external funding could be emulated in other areas.

Personnel and training requirements are needed. Currently, military officers involved in GHE activities are largely self-selected through interest in this type of activity that is balanced with other requirements. Each military Service is addressing this issue in its own way. The Air Force International Health Specialist (IHS) program, which began in 2001, fosters an understanding of regional and global health issues, geopolitical issues, and joint planning methods. Air Force Health Service personnel may apply for IHS special experience identifiers based upon past experience in global health activities, foreign language proficiency, cross-cultural skills, and completion of minimum training requirements. The Navy is approaching GHE through the development of an Additional Qualification Designator that serves as a means to identify health professionals who meet certain competency requirements coupled with global health-related training, education, and experience. The authors of this article support ongoing efforts to establish a joint solution to this issue and encourage clear guidance in the near future. Extant education and training opportunities could be combined to form a core curriculum to which services may add instruction on unique capabilities or issues.

<img src="/Portals/68/Images/jfq/jfq-80/cullison-et-al-3.jpg" alt="U.S. Southern Command conducts New Horizons Honduras 2015 joint humanitarian assistance training exercise with partner nations in Central America,

South America, and Caribbean, June 27, 2015 (U.S. Air Force/David J. Murphy)" width="100%" />

U.S. Southern Command conducts New Horizons Honduras 2015 joint humanitarian assistance training exercise with partner nations in Central America,

South America, and Caribbean, June 27, 2015 (U.S. Air Force/David J. Murphy)

Data regarding GHE effectiveness, both from a health and a strategy perspective, is sorely lacking. Outcome studies in terms of both health and strategic results are needed to evaluate current efforts and guide future programs. Congress emphasized this point in section 715 of the 2013 National Defense Authorization Act. Current work on a measures of effectiveness process and learning tool is well under way. This capability can be helpful to military academic institutions such as National Defense University, USUHS, and Service war colleges, which seem ideal centers for such study. As suggested in the 2013 Secretary of Defense GHE cable, a percentage of funding earmarked for monitoring and evaluation could be used to support these efforts. We understand that working groups have been chartered to study many of the issues raised above. We encourage close evaluation of their work and, if appropriate, immediate implementation of their recommendations.

We are encouraged by excellent progress in developing a strategy for military global health engagement that balances the security dimension with a holistic national and international approach to major global health issues. Continued emphasis on health issues of international importance, particularly in regions of strategic importance to the United States, will result in a healthier, safer world. JFQ

Notes

1 Joseph Nye, Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power (New York: Basic Books, 1990).

2 Department of State and U.S. Agency for International Development, Leading Through Civilian Power: The First Quadrennial Development and Diplomacy Review (Washington, DC: Department of State, 2010), available at <www.state.gov/documents/organization/153142.pdf>.

3 Josh K. Michaud, Kellie Moss, and Jennifer Kates, U.S. Global Health Policy: The U.S. Department of Defense and Global Health (Washington, DC: The Kaiser Family Foundation, 2012), available at <http://kff.org/global-health-policy/report/the-u-s-department-of-defense-global/>.

4 Alison Lawlor, Amanda Kraus, and Hayden Kwast, Navy-NGO Coordination for Health-Related HCA Missions: A Suggested Planning Framework (Arlington, VA: CNA Corporation, 2008), available at <www.dtic.mil/get-tr-doc/pdf?AD=ADA491274>.

5 Richard Downie, ed., Global Health as a Bridge to Security: Interviews with U.S. Leaders (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2012), available at <http://csis.org/files/publication/120920_Downie_GlobalHealthSecurity

_Web.pdf>.

6 James B. Peake et al., The Defense Department’s Enduring Contribution to Global Health: The Future of the U.S. Army and Navy Overseas Laboratories (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2011).

7 United Nations (UN), The Millennium Development Goals Report 2014 (New York: UN, 2014), 34–39, available at <www.un.org/millenniumgoals/2014%20MDG%20report/MDG%202014%20

English%20web.pdf>.

8 UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Oslo Guidelines: Guidelines on the Use of Foreign Military and Civil Defence Assets in Disaster Relief, Revision 1.1 (New York: UN, 2007), available at <https://docs.unocha.org/sites/dms/Documents/Oslo%20Guidelines%

20ENGLISH%20%28November%202007%29.pdf>.

9 Eugene V. Bonventre, Kathleen H. Hicks, and Stacy M. Okutani, U.S. National Security and Global Health: An Analysis of Global Health Engagement by the U.S. Department of Defense (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2009), available at <http://csis.org/files/publication/090421_Bonventre_USNationalSecurity _Rev.pdf>.

10 J. Christopher Daniel and Kathleen H. Hicks, Global Health Engagement: Sharpening a Key Tool for the Department of Defense (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2014), available at <http://csis.org/files/publication/140930_Daniel_DODGlobalHealth_Web.pdf>.

11 Secretary of Defense “Policy Guidance for DOD Global Health Engagement,” May 13, 2013, available at <www.cdham.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/2013-Policy-Guidance-fo-DOD-Global-Health-Engagement.pdf>.