Over the past several years, a number of authors addressing professional military education (PME) have expressed frustration about and occasionally disdain for retired military officers who serve on the faculties of Department of Defense (DOD) senior-level colleges (SLCs).1 In a 2011 article, Dr. George Reed, a former U.S. Army War College (USAWC) faculty member, stated, “Their [retired military on faculty] experiences have a shelf life that begins to expire on the date of retirement. They can usually be counted on to run a good seminar, but few contribute much in terms of scholarship as measured by the usual indicators of research and publication.”2 The authors are not in a position to defend those PME faculty members who have not performed well. However, it appears that the critics do not understand that retired military officers bring a specific body of knowledge of operational and strategic expertise to PME—in most cases acquired through years of experience.

This is a body of professional knowledge that SLC graduates must master to be effective strategic planners, advisors, and leaders. Retired military officers on a Service SLC faculty have an important role in preparing students for service at the strategic level. The faculty must know the past and current state of practice of operational and strategic planning, integrate new concepts into a continually evolving curriculum, understand the contemporary strategic environment, and convey this knowledge to a diverse student body.

The faculty, referred to here as professors of practice (PoP), are largely retired military faculty involved in teaching the professional knowledge related to theater strategy and campaign planning. This article explains the term professors of practice and examines some of the factors that affect how they maintain currency in the professional body of knowledge. It then describes how the changing strategic environment affects PoP currency and offers ways they can acquire and disseminate this information to students and faculty. Finally, it offers a number of actions organizations within DOD can take to support PoP more effectively.

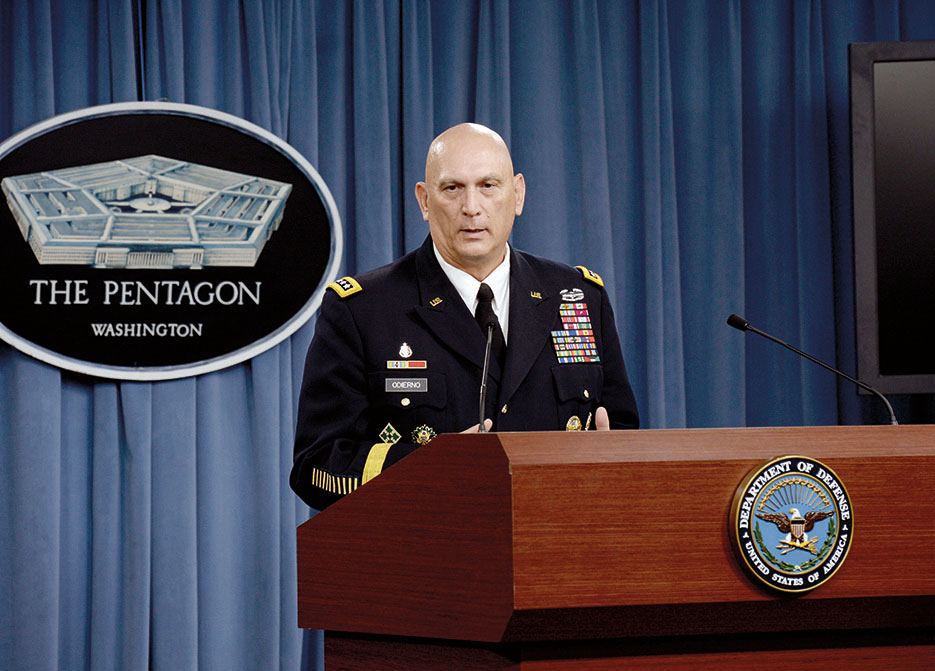

Then–Army Chief of Staff General Raymond Odierno discusses Service challenges during Pentagon briefing, August 2015 (DOD/Clydell Kinchen)

Who Are Professors of Practice?

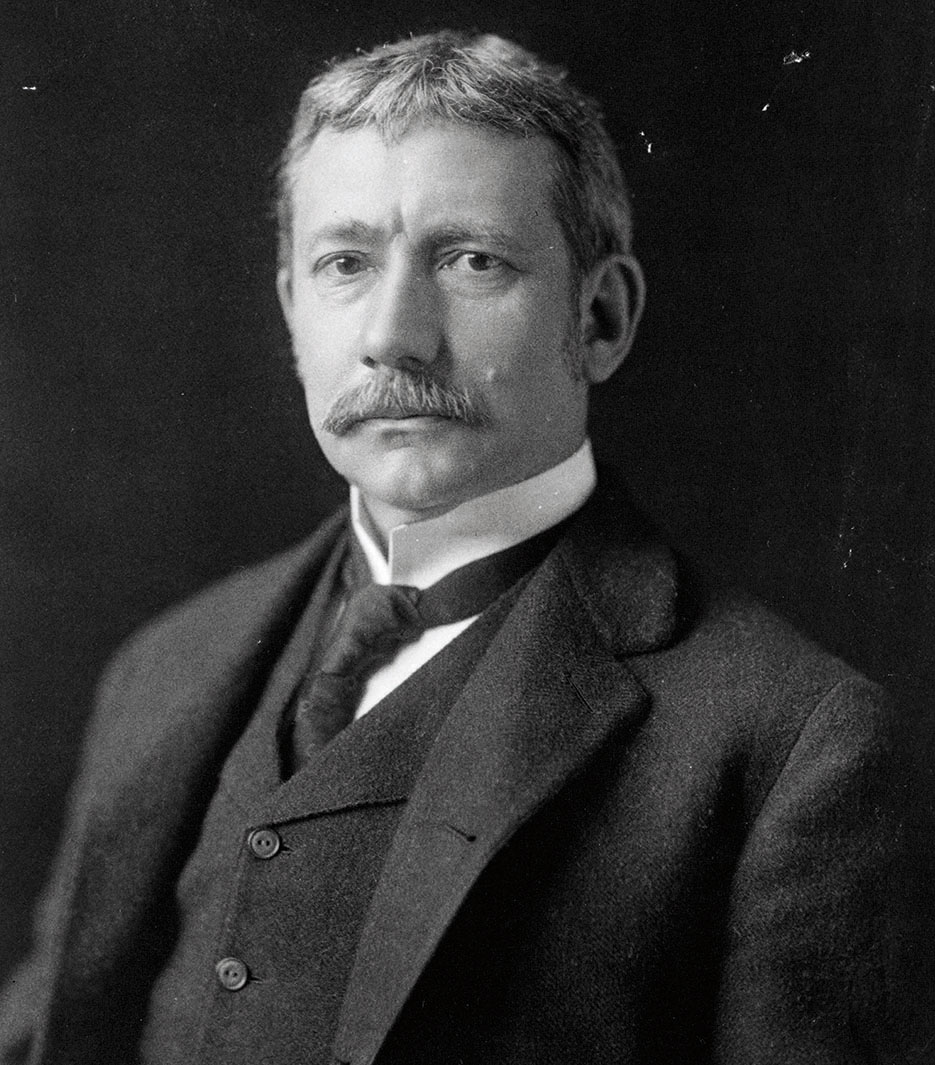

The USAWC School of Strategic Landpower consists of four teaching departments: the Department of Distance Education and three resident course teaching departments that roughly align to address the three “great problems” that former Secretary of War Elihu Root articulated over 110 years ago: national defense, military science, and responsible command.3 This article focuses on those who teach military science in the School of Strategic Landpower, although many of the ideas presented also apply to those who teach other aspects of the professional body of knowledge. Military science is not a descriptive term, but two documents—U.S. Code Title 10 and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS) Instruction 1800.01D, titled “Officer Professional Military Education Policy (OPMEP)”—provide some clarity on what the Service SLCs granting Joint Professional Military Education Phase II must teach. These two documents require Service SLCs to include instruction on “theater strategy and campaigning” and “joint planning processes and systems” in the curriculum.4

The focus of the OPMEP is clear regarding the goals of Service SLC education: “To prepare students for positions of strategic leadership and advisement; senior education focuses on national security strategy, theater strategy and campaigning, joint planning processes and systems, and joint interagency, intergovernmental, and multinational capabilities and integration.”5

PoP Qualifications

The OPMEP addresses Service SLC faculty qualifications but with little specificity. For civilian faculty, which includes retired military, “The Services and NDU [National Defense University] determine the appropriate number of civilians on their respective college faculties. Civilian faculty members should have strong academic records or extensive professional experience” (emphasis added).6 In the case of PoP, extensive professional experience is essential given that most of the subjects they must address have no analogue in civilian graduate degree programs.7 In addition to the broad guidance in the OPMEP, faculty qualification requirements in a recent job announcement for a PoP position at the USAWC included the following: “Ability to prepare, teach, and lecture on subjects related to the theory and practice of military strategy, campaign planning, defense management, and joint and combined military operations.”8

Factors Affecting PoP Currency

There are a number of significant differences in how PoP and teachers of other professions, such as medicine, maintain currency. These differences generally fall into two categories. The first are the challenges in generating opportunities for PoP to maintain currency in the professional body of knowledge through practice. The second relates to the changing strategic environment. Although understanding the strategic environment is not explicitly part of the body of knowledge, it is an essential aspect in planning and, as shown, is a well-documented shortcoming in DOD planning over the past decade.

Medical school faculty members generally work in positions where they are able to practice their profession concurrent with teaching. This ability to practice would certainly help PoP maintain currency, but at a Service SLC, they do not enjoy the same opportunities for three reasons.

First, PoP are geographically separated from the offices and military organizations (for example, combatant commands and joint force headquarters) that translate national policy into executable military plans. Second, in addition to the physical separation, planning for the employment of military forces at any level requires a team approach. This team includes experts from all staff elements within the headquarters, interagency and multinational partners, and potentially nongovernmental organizations. This team establishes local procedures in addition to the guidance provided by policy and processes described in joint doctrine. While PoP have special expertise, it normally takes time for any newcomer to establish the credibility and trust essential to becoming an effective member of any high-performing team. Integrating a PoP into an engaged planning team in a timely fashion could be difficult under the best of circumstances.

Finally, there is a temporal aspect that precludes engagement by PoP through a complete contingency planning cycle. The near-term goal for developing contingency plans is 1 year, but a CJCS instruction states, “This goal assumes [as of now incorrectly] that APEX [adaptive planning and execution] planning tools and technologies has [sic] been fully implemented.”9 Episodic engagements by PoP with a joint headquarters during a planning cycle would certainly strengthen professional expertise, provide relevant perspectives, and help validate SLC curricula. Actual opportunities for a PoP to work through a complete planning cycle, though, are rare because of time considerations, faculty availability from teaching duties, and the cost of an extended temporary duty deployment at a joint or Service planning headquarters.

Maintaining Currency

The constantly evolving national security environment in which PoP operate requires various organizations within the U.S. Government to review and, if necessary (due to world circumstances or Federal law), publish new national strategic guidance, policy, concepts, and doctrine. All of these documents are part of the PoP professional body of knowledge and affect currency and curriculum development. Two figures illustrate the scope and variety of these sources. Figure 1 is a partial list of government documents published after September 11, 2001, that PoP incorporated into curricula. Figure 2 lists doctrinal or theoretical concepts from the same timeframe. There are a number of points worth noting in these figures. Dr. Joan Johnson-Freese believes that Active-duty military with current experience should be the first choice in selecting faculty for the topics PoP address.10 Recent operational experience is valued but is not necessarily the answer to better faculty. Figure 1 shows that some component of the professional body of knowledge changed each year between 2001 and 2013. If this trend continues, all faculty members, no matter how recent their operational experience, would have to understand and incorporate new guidance, concepts, or doctrine into the curriculum within a year or two. In figure 2, note the short shelf life of several concepts to appreciate the flux experienced by PoP. An additional challenge arises as several of these concepts were never codified in joint doctrine, yet the OPMEP requires PoP to dedicate classroom time to them even in their embryonic states.11

The Professional Body of Knowledge

PoP maintain currency in the professional body of knowledge through a combination of structured institutional support and significant individual effort. The OPMEP requires the Joint Staff J7 Joint Education Branch to host a Joint Faculty Education Conference (JFEC) every year. The conference’s purpose is to “present emerging concepts and other material relevant to maintaining curricula currency to the faculties of the PME and JPME colleges and schools.”12 The JFEC is held each summer, and the J7 hosts invite representatives of the PME community. DOD representatives’ presentations focus on the evolving professional body of knowledge, but they also provide insight into the strategic environment.

There are numerous classified and unclassified policy and strategy documents directly related to PoP expertise (figure 1). PoP invest a significant effort to remain current. Although the faculty at Service SLCs cannot use classified documents in class because of the presence of international fellows, they serve as an important source for PoP expertise. Detailed knowledge of these documents is essential to shape the curriculum that respects security considerations while ensuring relevance to U.S. practitioners.

Articles in professional journals serve as valuable sources of PoP knowledge, both as sources of content and as vehicles for research and contributions by PoP to share new knowledge. Students invariably raise numerous topics for scholarly research such as flawed concepts, doctrinal voids, and inconsistent policies during seminar discussion. There are a number of other ways PoP maintain currency:

- Faculty development. While the PoP at the USAWC join the faculty with considerable operational and planning experience, the subject matter they address in class is so broad that no one person can be an expert on all facets of the theater strategy and campaigning curriculum (Root’s “military science”). Effective faculty development programs at the institutional and departmental levels ensure all PoP have a common understanding of current strategies, concepts, doctrine, and the strategic environment. Faculty development is an opportunity for new faculty to share their recent operational experiences and for PoP to offer perspective, expertise, and instructional techniques to their new colleagues. This structured mentoring is especially valuable to new teachers who must coach SLC students in conceptual skills that will enable them to operate in the unfamiliar, uncomfortable, and complex strategic environment that is the new reality of their post-SLC studies.

- Reference handbooks. Publications that integrate current doctrine and best practices or consolidate diverse information into one document provide PoP with superb professional development references. Two examples are the USAWC Campaign Planning Handbook and the U.S. Naval War College’s Forces/Capabilities Handbook.

- Inputs to joint doctrine. Inputs to doctrine contribute to the body of knowledge, and while the author is never acknowledged, changes to doctrinal publications undergo an extensive peer review process by practitioners.

- Optional lectures. Throughout each academic year there are numerous opportunities to expand professional expertise through optional lectures provided by a variety of subject matter experts on relevant topics.

- Supervise student research. PoP can maintain currency by serving as advisors for student research projects.

Retired Admiral James G. Stavridis, dean of Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University, speaks at U.S. Naval War College, December 2014 (U.S. Navy/James E. Foehl)

Understanding the National Security Environment

In addition to the professional body of knowledge, another component of PoP expertise is an understanding of the strategic environment. PoP educate students on the importance of integrating the effects of the environment when applying the professional body of knowledge to U.S. national security challenges. Two studies document the undesirable results that occur when U.S. strategic leaders failed to adequately understand the environment during planning and execution.

The first lesson, documented in a 2012 study by the Joint and Coalition Operational Analysis division of the Joint Staff J7, concerned a failure to understand the environment. The study concluded, “A failure to recognize, acknowledge, and accurately define the operational environment led to a mismatch between forces, capabilities, missions, and goals.”13 The second reference is a 2014 study by the RAND Corporation titled “Improving Strategic Competence.” This study critiques the U.S. strategic effort over the past 13 years. The authors make clear one of their findings in the section titled “Military Campaigns Must Be Based on a Political Strategy, Because Military Operations Take Place in the Political Environment of the State in Which the Intervention Takes Place.”14 The study concludes the U.S. military did not adequately understand the political environment in the process of developing plans for Afghanistan and Iraq.

This requirement for environmental understanding is a recent addition to doctrine and PoP expertise. Introduced into joint doctrine in the 2011 version of Joint Publication 5-0, Joint Operation Planning, operational design methodology assists the commander in developing an operational approach. Three aspects of the methodology leading to an operational approach are understanding the strategic direction, understanding the operational environment, and defining the problem.15

In a memorandum describing the six officer-desired leader attributes for Joint Force 2020, General Martin Dempsey included the ability “to understand the environment and the effect of all instruments of national power.”16 Reinforcing General Dempsey’s emphasis on this environmental understanding, Army Chief of Staff General Raymond Odierno sent a letter containing guidance to Major General William Rapp, the newly appointed commandant of the USAWC. Among other tasks, General Odierno asked Major General Rapp to ensure he understood the strategic environment to include “maintaining your current sense of the global and Washington atmospherics.”17 In a USAWC faculty town hall meeting on September 29, 2014, Major General Rapp repeated that charge to the faculty to ensure the students also understood those aspects of the national security environment.18

It is fair to conclude that SLC graduates could learn what they need to know about the environment in their post-graduation assignments. However, this delay in effectiveness flies in the face of the vision for USAWC graduates as articulated by the previous commandant, Major General Anthony Cucolo. One slide in his command briefing stated:

Our primary purpose is to produce graduates who are skilled critical thinkers and complex problem solvers . . . who have rethought their professional identity for continued service at senior levels . . . and who, upon graduation, can immediately [emphasis in the original] be value-added in an advisement or leadership role at the strategic level anywhere in the joint force or the interagency.19

The need for PoP to understand and convey relevant aspects of the strategic environment to students is clear. Achieving that environmental understanding is a significant challenge for all PoP and is complicated by decisions regarding sources of information relevant to the curriculum and restrictions on disseminating environmental insight.

Graduates listen as General Dempsey delivers commencement address at National Defense University graduation ceremony in Washington, DC, June 18, 2015 (DOD/Daniel Hinton)

Achieving an Understanding of the Strategic Environment

The effort by PoP to maintain currency regarding the environment is a never-ending and time-consuming task. Fortunately, PoP do not suffer from a lack of sources regarding this aspect of the profession. On the contrary, determining what is relevant and timely for lesson development or inclusion in seminar dialogue given the multitude of unclassified information outlets is a challenge. Examples of open source information range from recently published books, journals, and blogs to unclassified daily summaries of U.S. military activity. PoP must engage in environmental scanning daily and be good team players. PoP who find open source material that provides insight into the dynamic strategic environment and supports lesson or course objectives must freely share this information with colleagues. Taken to the extreme, PoP inboxes could be overflowing with interesting but not necessarily relevant environmental insight. This is where PoP experience makes a difference: understanding what is and is not important in making critical points in class. Fortunately, sharing relevant environmental insight is something the professionals in the authors’ department have done well for years.

While open sources are an important source of environmental awareness, information from government insiders provides environmental understanding that is extremely valuable to students and faculty. However, access limitations and constraints on dissemination of this information pose a peculiar challenge for PoP and affect currency.

Over the course of the academic year, students often hear faculty and guest speakers declare that “relationships matter.” For PoP, relationships are critical. Maintaining contact with former students who are in relevant operational assignments is an effective way for PoP to maintain a feel for the strategic environment.

PoP can gain an understanding of the environment through primary source interviews or interactions with senior members of DOD and interagency and multinational partners who deal with operational and strategic level challenges daily. The dedicated public servants who formulate and implement U.S. national policy are in ideal positions to provide clarity regarding the strategic environment. Unfortunately, these national security professionals are busy and do not have the time to document their observations in an effort to enlighten PME faculty.

Access to sources that have special insight is the first challenge. Relationships developed between senior government officials and PoP have served the faculty well at USAWC. These relationships, established during coincident assignments or student contacts, translate into access where PoP are able to obtain and share with faculty colleagues insights regarding current policies and practice. These relationships do not grow overnight, but once they are established, many PoP are able to tap into individual expertise that is simply not available to other faculty or the public at large. The USAWC leadership recognizes the importance of access. A qualification in a recent job announcement for a Chair of War Studies was an “extensive professional network enabling access to academic institutions, think tanks, government agencies, non-governmental organizations, etc.”20

The second challenge PoP face is that once acquired, dissemination of this environmental insight to a wide audience is affected, in part, by the USAWC policy regarding attribution of comments to sources.21 Engagements with senior government officials or other subject matter experts who are not candid would not be useful to faculty or students. Source perspectives on the environment are enlightening but are often sensitive. The nonattribution policy protects those who are willing to provide insights, but this policy also limits the ability of PoP to document source insights in publicly available media. Another factor that limits dissemination of environmental perspective is the classification of the insight. Discussions with high-level sources frequently involve classified information, and there are restrictions on how this information is shared with colleagues and students.

While PoP will gain great insight from engagements with the sources described thus far, it is essential that a wider audience (for example, faculty colleagues and students) benefit from these activities. Dr. George Reed’s comment regarding PoP “scholarship as measured by the usual indicators of research and publication” does not necessarily account for how PoP share environmental insight. The “usual indicators of research and publication” may not be relevant or useful in helping PoP and students understand the strategic environment.

Nonstandard Contributions to the Body of Knowledge

Scholarly articles have an important role in ensuring PoP currency, but there are a few drawbacks in relying on peer-reviewed journal articles to disseminate insight on the strategic environment. First is timeliness of an article. In a rapidly changing environment, traditional publication review and publishing processes might not keep up. As an example, Anthony Cucolo and Lance Betros authored an article for the July 2014 edition of Joint Force Quarterly regarding changes at the USAWC. During the peer review and publishing process, the USAWC leadership changed direction and moved away from some of the curriculum initiatives the authors presented.22 A journal article regarding publications describes this situation:

Former Secretary of War Elihu Root (Wikipedia)

As the rate of societal change quickens, cycle-times in academic publishing, which have lagged behind those in industry and technology, become crucial. In a world of instant communication in which 70 million blogs already exist and 40,000 new blogs come on line each day—the majority of which are not in English—academia cannot continue to rely on a venerated journal-publishing system that considers publication delays of up to two years to be both acceptable and normal.23

Another consideration is the need for the PME community to recognize that peer review may not apply to environmental insight. There is no doubt that peer review is a valuable tool for proposed additions to the professional body of knowledge. However, for environmental aspects of the profession, first-person accounts do not lend themselves to peer review. Washington, DC, atmospherics are about perceptions and opinions of the environment, and these opinions matter if one wants to operate effectively in the environment. When Eliot Cohen entered government service in 2007, he believed that “policy was forty percent substance and sixty percent personalities.” As a result of his service in the Department of State, his view changed: he now believes government policy is “ten percent substance and ninety percent personalities.”24 Personalities change with every administration, and documented policy cannot always keep up. A recent example is the difference between the current practice regarding the Secretary of Defense campaign and contingency plan reviews and the current policy as articulated in a CJCS instruction.25 Substantive differences such as these are important to Service SLC graduates who must operate in this environment and the PoP who must integrate these realities into the curriculum.

Trip reports, blog entries, online journals, and other nonstandard representations of new knowledge are ways PoP disseminate environmental realities to a relevant audience. These methods do not have the cachet of journal articles and may not have any enduring value. However, timely, relevant, and accurate insight into the strategic environment in any form arguably supports PoP currency and student learning.

Recommendations

A number of current policies and processes within DOD and the USAWC support the continuing education and development of PoP. However, the institution could do more if it seeks to extend PoP shelf life and leverage the years of teaching experience, context, and perspective that PoP bring to the classroom. Those responsible for PME within DOD should establish a system to disseminate critical references relevant to OPMEP requirements to the PME institutions. As noted above, PoP must have access to and integrate into the curriculum a never-ending flow of new strategic guidance, policy (classified and unclassified), concepts, and doctrine. The Joint Staff J7 Joint Education Branch could act as a clearinghouse for strategic guidance, policy, and concept documents and push them to each of the institutions involved in PME, similar to how it currently provides joint doctrine updates. This should include concepts and other strategic documents that are in draft with an anticipated date of release.

The Joint Faculty Education Conference is a great start to every academic year. It provides current insights for PoP and sets the stage for curriculum refinement. One change the J7 should consider is to conduct the JFEC in a classified forum. It is through access to classified insight and material that PoP will achieve the level of understanding of systems, processes, and concepts to shape the classes that serve the U.S. audience while respecting classification considerations.

Unfortunately, a JFEC-like conference once a year is not enough to enable PoP to maintain currency with respect to the strategic environment. Three proposals could help provide critical insight between the annual JFEC. First, J7 could host classified blogs available to those involved in policy development and planning, ranging from the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) Policy to the joint force headquarters involved in operational/strategic planning. Second, J7 could develop a system similar to the server list called STRATLST that connects Army strategists via email. It has generated great participation and insight among practitioners and PoP. The one disadvantage is that the Army STRATLST operates on an unclassified network, which limits usefulness.26

Finally, OSD Policy or the Joint Staff J5 Joint Operational War Plans Division could host a global brainstorming session on a regular basis to provide PoP with best practices among practitioners on status of policy and concepts between the annual JFEC. One of the authors recently participated in such a session unrelated to national security, but if done in a classified forum, it appears to be an ideal way to get worldwide input from practitioners on a variety of issues.27

There are a few other ways PME leadership can support PoP efforts to maintain currency.

- Leadership in PME must resource regular staff visits to relevant organizations and commands. These visits, while expensive, are critical in ensuring PoP currency and relevance.

- Service SLCs should actively seek and resource PoP engagements with joint planning or policy development organizations for an extended period. This would normally be part of a PoP sabbatical. The Services, however, must support the SLCs with additional faculty to enable these extended operational support opportunities.

- Curriculum developers must engage subject matter experts who are outside of the Federal Government. These experts offer PoP and students a broader perspective leading to a better understanding of the environment.

Absent efforts to maintain currency, everyone involved in education, not just retired military officers in PME, has a shelf life. Because of the challenges outlined above, PoP will not be able to engage in their practice similar to teachers of other professions. It is not a foregone conclusion that PoP will become stale, though. With hard work, additional institutional support, and acceptance of nonstandard forms of new knowledge, there is no reason why PoP in Service SLCs cannot continue to grow professionally while maintaining an understanding of the evolving strategic environment. In fact, most competent PoP do maintain contact with their former students and others to gain that critical understanding of what is happening around the globe and how senior headquarters are adapting to changing political landscape. For officers and government civilians rising into the ranks of advisors to senior leaders and ultimately as senior leaders themselves, what could be more important in the PME environment than supporting PoP who prepare these committed professionals for years of valuable service to the Nation? JFQ

Notes

- Joan Johnson-Freese, “The Reform of Military Education: Twenty-Five Years Later,” Orbis (Winter 2012), 147, 151. In a discussion of practitioners, she states, “What they [retired military officers] know tends to be an asset that declines in value the longer they are away from their area of professional activity.” She goes on to say that “Active duty military officers are crucial to the PME mission, and should be the first choice to teach the courses on operational warfare, not former officers far removed from current experience.”

- George Reed, “What’s Right and Wrong with the War Colleges,” Defense Policy Journal, July 1, 2011, available at <www.defensepolicy.org/george-reed/what’s-wrong-and-right-with-the-war-colleges>.

- These words were part of a speech Elihu Root gave during the laying of the cornerstone of the Army War College at Washington Barracks, February 21, 1903.

- Armed Forces, 10 U.S.C. § 2155 (2011); and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS) Instruction 1800.01D with Change 1, “Officer Professional Military Education Policy (OPMEP),” September 15, 2011, 1.

- CJCSI 1800.01D with Change 1, A-A-5.

- Ibid., B-3.

- GraduateGuide is a Web site that provides a directory of graduate schools in the United States and Canada. The site groups graduate majors into 52 broad categories. A search using several criteria showed that civilian graduate universities do not offer most of the subjects relating to “military science” that the OPMEP requires Service SLCs to address.

- Announcement NEDQ141197706, “Professor of Operational Art,” USAJobs.gov, accessed at <www.usajobs.gov/GetJob/ViewDetails/379212900>.

- CJCS Instruction 3141.01E, “Management and Review of Joint Strategic Capabilities Plan (JSCP)-Tasked Plans,” September 2011, B-15.

- Johnson-Freese, 147.

- CJCSI 1800.01D with Change 1, E-E-2. Joint Learning Area 3, Learning Objective a, states, “Evaluate the principles of joint warfare, joint military doctrine, and emerging concepts in peace, crisis, war and post-conflict.”

- Ibid., C-3.

- Joint and Coalition Operational Analysis Division (JCOA), J7 Joint Staff, Decade of War Volume 1: Enduring Lessons from the Past Decade of Operations (Suffolk, VA: JCOA, June 15, 2012), 2.

- Linda Robinson et al., Improving Strategic Competence: Lessons from 13 Years of War (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Arroyo Center, 2014), 52–53.

- Joint Publication 5-0, Joint Operations (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, August 2011), III-22.

- Martin E. Dempsey, “Desired Leader Attributes for Joint Force 2020,” memorandum for Chiefs of the Military Services, Washington, DC, June 28, 2013.

- William Rapp, email message to authors, October 2, 2014.

- William Rapp, briefing, U.S. Army War College, Carlisle, PA, September 29, 2014. Used with permission.

- Command briefing, U.S. Army War College, Carlisle, PA, May 2, 2014.

- Announcement NEDQ1264682, “Chair of War Studies,” USAJobs.gov, accessed at <www.usajobs.gov/GetJob/ViewDetails/387161800>.

- U.S. Army War College, “Carlisle Barracks Pamphlet 10-1: Administrative Policies and Procedures for Students, Faculty and Staff,” June 2011, 2–10.

- Anthony Cucolo and Lance Betros, “Strengthening PME at the Senior Level: The Case of the U.S. Army War College,” Joint Force Quarterly 74 (3rd Quarter 2014), 50–57.

- Nancy J. Adler and Anne-Wil Harzing, “When Knowledge Wins: Transcending the Sense and Nonsense of Academic Rankings,” Academy of Management Learning and Education 8, no. 1 (March 2009), 72–95.

- Eliot A. Cohen, discussion with the U.S. Army War College Advanced Strategic Art Program during a National Security Staff Ride, Washington, DC, February 9, 2014. Used with permission.

- Paul Martin, “Adaptive Planning and GEF Review,” lecture, Joint Faculty Education Conference, Washington, DC, June 24, 2014. Used with permission.

- Nathan K. Finney, email to authors, November 5, 2014: “STRATLST is a professional e-mail forum for strategists and interested individuals.” Francis Park, email to authors, November 5, 2014: “Today there are 400 subscribers, with U.S. military members across all four services ranging from 1LT to general officers, as well as allied officers and civilian academics.”

- From September 30, 2014, to October 2, 2014, Boston University School of Management hosted a business education “jam session” using IBM software (<www.collaborationjam.com>). During the session, worldwide practitioners were able to offer opinions on topics such as fostering ethical leadership, harnessing digital technology, and supporting 21st-century competencies.