The U.S. military today fights jointly. A joint commander—reporting to the Secretary of Defense—commands all Service components during military operations. And as a key sign of this jointness, combatant commanders no longer come solely from a single Service as they once did. In fact, the combatant commanders and their control of operations are often considered the greatest expression of jointness.

Chairman and Admiral Samuel J. Locklear, USN, commander, U.S. Pacific Command, talk before departing Camp Smith, Hawaii (DOD/D. Myles Cullen)

Yet the historical record suggests combatant commanders are not as joint as thought; a review of all combatant commanders by Service shows that each military branch has been represented roughly equally for the past 30 years. This consistent balance strongly suggests that Service-based prerogatives still play a role in selecting who commands even the operational commands. If inter-Service politics pervades even the selection of combatant commanders, how much more might it affect those parts of the military commonly acknowledged as less joint—especially acquisition?

Such visible evidence of inter-Service politics belies the more hopeful claims for jointness, underlining that jointness is not a synonym for a unified military but rather a description of a loose collaboration among the Services. The U.S. military must stop using jointness as a euphemism and accept a loss of Service prerogative to ensure more effective defense administration and, more importantly, a more effective fighting force.

The Combatant Commands and Jointness

Combatant commanders sit at the pinnacle of operational command in the U.S. military system. Though the U.S. military is organized, trained, and equipped by the four Services—the Army, Marines, Navy, and Air Force—it is used by the combatant commanders. That is, when forces are tasked to a mission, they come under the charge of the combatant commander who plans and executes operations using forces from all the Services together. Combatant commands are divided between geographic and functional commands. For the geographic commands, the U.S. military divides the entire world into six commands that oversee all forces conducting missions in those regions: European, Pacific, Central, African, Northern, and Southern. The functional commands are Transportation, in charge of getting troops and equipment around the world; Strategic, responsible for operating all U.S. nuclear forces; and Special Operations, not surprisingly, in charge of all special operations forces. During operations, the combatant commander is responsible for effectively using and integrating forces from all Services. But when not tasked to a mission, these forces all belong to an administrative command, which reports through the chain of each distinct Service.

In the past, that administrative chain owned by the Services tended to overshadow the operational chain. Even in World War I, General John Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) in France, jockeyed with General Peyton March, the Chief of Staff of the Army in Washington, over what each had responsibility for and what the reporting chain was. According to Pershing’s Chief of Staff General James Harbord, as quoted by Kenneth Allard:

General Pershing commanded the AEF directly under the President and Secretary of War, as the President’s alter ego. No military power or person was interposed between them. . . . No successful war has ever been fought commanded by a staff officer in a distant capital. . . . The organization effected in our War Department . . . scrupulously preserves the historic principle that the line of authority runs directly from the highest in the land to the highest in the field.

Allard notes, however, that “that principle was not as clear to some people as it apparently was to General Harbord.”1

In World War II, the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) arose as the body to adjudicate between the needs and desires of the theater commanders—though one of the four chiefs was Admiral William Leahy who was Chief of Staff to President Roosevelt, not one of the Services. After the war, the JCS was enshrined statutorily, creating blurry responsibility for the Service chiefs who were in charge of both the overall welfare of their Services and U.S. military operations.

President Dwight Eisenhower set out to clarify this confusion in 1958 when his reorganization plan explicitly made the chain of command direct from President to Secretary of Defense to combatant commanders, cutting out the Service chiefs. But this clarity existed only in theory because, in practice, the Service chains continued to exercise significant influence over the Service component commands overseen by each combatant command. The Goldwater-Nichols Department of Defense Reorganization Act of 1986 explicitly acknowledged this subversion of Presidential and legislative intent and succeeded in ending it.

Supporters of jointness rightly point to Goldwater-Nichols as a watershed moment in empowering the combatant commanders and true joint operations. Since then, most agree U.S. military operations have more effectively drawn on forces from all Services and wielded them as a powerful force that cuts across all domains. Combatant commanders no longer represent their parent Service but the national interest. They are the best expression of how joint the U.S. military has become.

The Combatant Commands and the Services

Sitting at the pinnacle of operational command and exemplifying military jointness, combatant commanders are assumed to be chosen solely based on who is the best person for the job, regardless of what Service the commander comes from. Yet the consistent proportionality by Service of combatant commanders suggests that the Service they come from, and not only merit, matters in selection.

All the men (it has been only men so far) who have served in these positions have been accomplished people who have achieved a great deal in their careers, as one would expect. But considering these people individually ignores that the pool from which commanders are pulled only includes accomplished people with significant achievements; thus, such achievements may not tell us much about how or why each officer is selected. Acknowledging each officer as individually accomplished does not explain the continuity over time.

In the rare times when combatant commanders and their selection are considered systematically rather than individually, it is usually from a Service-centric perspective that bemoans an underrepresentation by one Service or another. For instance, a 2008 Air Force Magazine article titled “Why Airmen Don’t Command” purported to chronicle that Air Force officers are underrepresented in regional combatant commands.2 Another example is a 2007 article in which “Retired Army Maj. Gen. Robert Scales, former head of the Army War College who holds a Ph.D. in history from Duke University, said he could find no prior period when the Army was so engaged overseas and so underrepresented at top levels.”3

These arguments not only miss but also obscure the most important aspect of who has commanded combatant commands: leaders representing an even balance among the military Services.

To demonstrate how well balanced across the Services the combatant commanders have been, we have to acknowledge two points: because the number of combatant commanders is so small we cannot just consider any given moment in time, and there have been changes over time in how the Services are represented in the combatant commands. Once we have accounted for these two points, we can offer an objective, quantitative comparison to see if inter-Service politics does affect how combatant commanders are chosen.

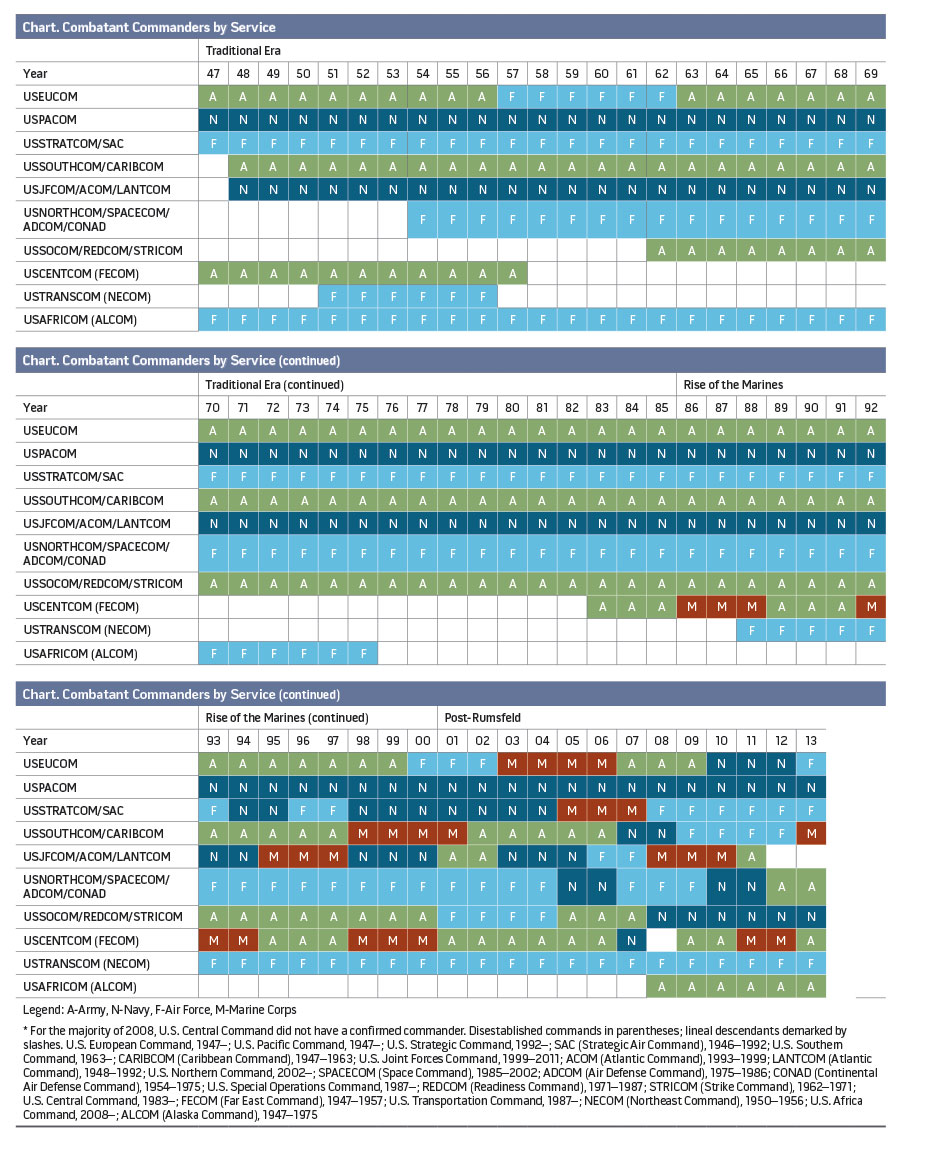

On the first point, there are currently only 9 combatant commanders, as many as there have ever been except for the 4 years after the creation of U.S. Africa Command (USAFRICOM) and before the dissolution of U.S. Joint Forces Command (USJFCOM), when there were 10. That means changes of just one commander can cause big swings in the percentage by Service, and since the average commander’s tenure is less than 3 years, there are a number of changes in the slate of commanders. At any given moment, such changing rosters can give the impression of an unbalanced slate of commanders, substantiating those looking to believe a Service is underrepresented. To correct for these swings, we need to look at the combatant command rosters over time, which is easily done by considering the roster by combatant command by Service by year. So our basic unit is a flag officer from whichever Service held a combatant commander for the bulk of every year (commanders by Service by year). Even then, there is only a small sample size. But we can look over any time period we want and have a standard way to compare the balance of commanders by Service. See the chart for the history of the combatant commanders displayed this way.

As to the second point, times have changed since the original Unified Command Plan (UCP) was signed in 1946. But we must sort out what has changed. I argue there have been three distinct periods in the history of the combatant commands: the traditional era up until 1986, the rise of the Marines from 1986 until 2001, and the post–Donald Rumsfeld era since.

Traditional Era

In the traditional era from 1946 until 1986, combatant commands were largely extensions of the Services. Each had its role in the world, the unified commands were how it executed that role, and therefore the commander of each command came from that parent Service. This is not to say that the commanders did not command forces from all the Services. In fact, the UCP was intended to acknowledge one Service’s dominance over the others in region or mission, as the official history of the UCP states: “The impetus for the establishment of a postwar system of unified command over US military forces worldwide stemmed from the Navy’s dissatisfaction with this divided command [between General of the Army Douglas McArthur and Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz] in the Pacific.”4 The initial UCP did not actually resolve which five-star flag officer was in charge of the other, instead enshrining separate commands for the Army and Navy in the Pacific and further cementing the connection between the military Services and commands. Though jockeying continued between the Services over the shape of the commands and what regions or missions each controlled, five commands lasted throughout the 40 years of the traditional era: the Navy had Pacific Command and Atlantic Command, the Army had European Command and what became Southern Command, and the Air Force had the Strategic Air Command. The Army had two other commands: McArthur’s Far East Command, which was disestablished in 1957, and Strike Command, which was created in 1961, transitioned to Readiness Command, and eventually served as the administrative basis for U.S. Special Operations Command. In addition, the Air Force was responsible for various air defense commands.

Over the entire 40 years, there was only one instance where a commander did not come from the traditionally associated military Service: from 1957 to 1962, the Air Force’s Lauris Norstad commanded U.S. European Command (USEUCOM), a traditional Army command. The chart shows the long, unbroken years of single-Service combatant commands. Of course, we should not be surprised that during this traditional era the combatant commands were dominated by the Services. The traditional era is defined by the dominance of the Services over the combatant commands, and ending that dominance was one of the major goals of the 1953 and 1958 reorganizations, the recommendations of a Blue Ribbon Defense Panel in 1970, and the Goldwater-Nichols Act of 1986.

The Rise of the Marines

Goldwater-Nichols did succeed in breaking Service dominance of the combatant commands, but the legislative victory alone did not alter the pattern of who commanded each combatant command. Instead, the break required the rise of the Marine Corps as a full-fledged Service. Of the first four commands to be commanded by an officer not from its traditionally associated Service, three were commanded by Marines. The chart shows the late appearance of the Marines in red, at the first permanent break in the traditional affiliations.

The first Marine combatant commander was General George Crist of U.S. Central Command (USCENTCOM), who assumed command in November 1985, nearly a year before Goldwater-Nichols was signed into law. Maybe the more important law was the one signed in October 1978, which made the Commandant of the Marine Corps a full member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. A year later, the Commandant exercised this new authority to join the Chief of Naval Operations in opposing the other members of the Joint Chiefs and arguing for creating the predecessor to USCENTCOM rather than assigning forces for the Middle East to the Army-controlled Readiness Command. This argument led to the creation of USCENTCOM’s predecessor under a Marine lieutenant general. Though an Army general commanded USCENTCOM when it was formally established in 1983, Crist then assumed command after which a “longstanding gentlemen’s agreement among the service chiefs called for an Army general to relieve the Marine.”5 This rotation held for 20 years until Army General John Abizaid replaced Army General Tommy Franks in the middle of the Iraq War.

The next break in traditional arrangements came in 1994 when a Navy admiral assumed command of the newly created U.S. Strategic Command, successor to the Air Force–run Strategic Air Command. With the end of the Cold War, the Navy was willing to subordinate its nuclear submarines to a consolidated Strategic Command, with the provision that the command would rotate between the Navy and Air Force.

The end of the Cold War and the new jointness of Goldwater-Nichols also underpinned the next Marine combatant commander, General John Sheehan at Atlantic Command in 1994. Under direction of Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Colin Powell, Atlantic Command had begun a transition from a predominantly maritime regional command to what was called a “joint force integrator” command. Reflecting this change, “Speculation in the past had been that [the present commander’s] replacement would come from the ranks of the Army or Air Force, even though the command has been considered a maritime command for nearly 50 years.”6 However, the Marine was given the job, which meant the Marines had assured their ascension by keeping a combatant command even as USCENTCOM rotated back to the Army.

Three years later, a Marine was the fourth break in the traditional relationship between the Services and commands, as General Charles Wilhelm took the traditionally Army-dominated U.S. Southern Command. The traditional era was over, and the Services no longer could assume control over the commands that had once seemed like hereditary fiefdoms. Goldwater-Nichols created the statutory authority, the end of the Cold War created a strategic break from past assumptions, and, maybe most importantly, the rise of the Marine Corps proved a dramatic internal force to break the traditional relationship between the military services and the combatant commands.

Post-Rumsfeld Era7

Though the next break in traditional arrangements came before his tenure, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld forced the advent of a new era that seems to be holding.

Ironically, the next break after the rise of the Marines could be described as a rearguard action to restore the prerogatives of the military Services. In 2000, Air Force General Joseph Ralston replaced Army General Wesley Clark at USEUCOM, a traditional Army command. Though seemingly an example of breaking traditional relationships, Clark has implied that because he defended a combatant commander’s prerogatives in the face of Service resistance, he was replaced by a commander more inclined toward a Service perspective.8 In this case, one effect of Goldwater-Nichols may have overshadowed another.

But when Secretary Rumsfeld came to office, he was clear about his intention to break the traditional associations. As Andrew Hoehn, Albert Robbert, and Margaret Harrell state, “Rumsfeld was unsure, especially in the case of service leadership, that officers chosen by the current leadership—and, potentially, in the image of the current leadership—were best suited to question the status quo and lead a major transformation effort.”9 Also, Secretary Rumsfeld succeeded in putting nontraditional officers into commands: Marines were put into U.S. Strategic Command and USEUCOM, traditionally Air Force and Army commands, respectively. Navy admirals were put into U.S. Southern Command (USSOUTHCOM) and USCENTCOM, which despite the rise of the Marines had remained the province of generals from the ground forces. Another Navy admiral commanded U.S. Northern Command (USNORTHCOM), in charge of the continental United States and traditionally the province of the Air Force for air defense. And an Air Force general was the first non–sea Service commander of U.S. Joint Forces Command, the descendant of Atlantic Command. All these changes are reflected in the hodgepodge the chart becomes after Rumsfeld takes office.

However, Secretary Rumsfeld’s failure may be the most interesting case. In 2004, Rumsfeld nominated Air Force General Gregory Martin to head the U.S. Pacific Command (USPACOM), which had only been led by Navy admirals since its inception in 1947. One news story commented: “The Navy will cash a lot of chips to keep this from happening,” a retired general officer stated. “Get ready for the fight of the century.”10 After questioning at his confirmation hearing by former Navy officer Senator John McCain about his role in awarding the air refueling tanker contract, General Martin withdrew his name, and a Navy admiral eventually took command of USPACOM, which to this day has only been commanded by a Navy admiral.

With the departure of Secretary Rumsfeld, the selection of combatant commanders reverted to a process closer to the traditional one. No further challenge to the Navy’s hold of USPACOM has appeared, and Strategic Command has reverted to command by the Air Force. But the new jointness still holds. Since Rumsfeld’s departure, a Navy admiral was given USEUCOM, an Air Force general USSOUTHCOM, and an Army general USNORTHCOM, all firsts.

Frustrated Jointness

Times have changed. The combatant commanders’ role in U.S. foreign policy and their relationship to the military Services have changed. But having acknowledged that change and by looking over time, we can assess whether inter-Service politics plays a role in selecting combatant commanders. The military Services today are represented in the combatant commands almost evenly, suggesting inter-Service politics still matters, though not in the same way as during the traditional era.

During the traditional era, the Army, Navy, and Air Force allocated the combatant commands based on Service prerogatives. The Navy had fewer years of combatant commands because it did not share in the changing air defense commands the Air Force held or the functional command of first Strike and then Readiness Command the Army held. Of course, that was because the Navy did not want to be included in these commands: “The Navy and Marines wanted the Unified Command Plan to state that STRICOM [Strike Command] would consist only of Army and Air Force units. [Secretary of Defense Robert] McNamara refused but did not integrate Navy and Marine units into the command.”11 During the traditional era, inter-Service politics and their effect on combatant commands were blatantly open.

Yet despite a supposed decrease in Service influence, the balance of commands among the Services is more pronounced in the periods since the traditional era. With the rise of the Marines, the balance of command among the big Services closed to within 6 percentage points. The Navy kept its slightly smaller number and the Army had a slightly greater number by having three full-time combatant commands and its rotation in USCENTCOM. The Marines—newly represented from 1986 on—receive less than half the commands than the other Services receive in any period, but are actually disproportionately represented compared to the Corps’ share of the number of general officers, which is slightly under 10 percent.

The trend toward balance continued in the post-Rumsfeld era with ever greater parity, even though Secretary Rumsfeld had set out to diminish Service influence. In fact, during Secretary Rumsfeld’s tenure, the Army, Navy, and Air Force, respectively, had 18, 18, and 19 commands by year, with the Marines getting the other 8. The table displays the combatant commanders by Service by year, and the numbers and percentages show how evenly the commanders are pulled from the Services.

This balance is not just about appearances. The historical data are statistically consistent with a pattern of the three big Services each getting 3 out of 10 commands and the Marines getting the tenth. That is true for every period since the traditional era: from 1986 on, from 1986 to 2000, during Secretary Rumsfeld’s tenure from 2001 to 2007, or from 2001 on.12 In fact, even the geographic combatant commands are shared roughly evenly from 2001 on with no statistically significant difference. The Air Force is getting a greater share of geographic commands today than ever before, a reality nearly the opposite of the Service-centric concern cited earlier. As mentioned, the sample is a small one, so swings of one or two can have a big effect on the distribution across Services. Yet when the slate of commanders is considered over time rather than just as a snapshot, there is a remarkable consistency of balanced representation among the Services.

The consistency suggests there is a need to treat the Services equally when combatant commands are allocated. Because, over time, each Service gets its share of men assigned to combatant command, there is only a slight change on the “rotating schedule that gave the services ‘turns’ placing their top talent into specific positions, whether or not the person selected was the best fit for the position. This custom afforded each service a fair share of the top military positions,” which Hoehn, Robbert, and Harrell argue existed before Secretary Rumsfeld.13 Though it is highly unlikely that this balance among the Services is by chance, the balance itself does not prove that Service prerogatives cause it. But I would argue each Service is treated equally because today, more than a quarter of a century since Goldwater-Nichols, the Services still have independent political power, and the Secretary of Defense and President must be sensitive to that power. The Services in their own turn accept a fair share division of plums like combatant commands in order to keep the peace among themselves. This peace prevents significant inter-Service rivalry, but does so by accepting a shared and constrained role rather than forcing a full debate for the benefit of the civilian policymakers on the best man or Service or joint force for any given task.

Why It Matters and What to Do

If inter-Service politics still affects the most joint aspect of the U.S. military—the combatant commands—it most likely affects other aspects of the military, maybe even the outcomes of operations. To placate Service prerogatives, a commander or even the President may accept a less than strategically optimal set of forces or tasks. By doing so, a commander may, in turn, compromise U.S. national security objectives. Though almost no one argues that the skewing by Service interests today is as bad as it was in operations such as Grenada in 1983, it can still matter. Rajiv Chandrasekaran reported an example from Afghanistan and claims it affected the entire war effort:

The Marine commandant, Gen. James Conway, was willing to dispatch thousands of forces to Afghanistan as soon as the president approved a troop increase [but his] stipulations effectively excluded Kandahar. . . . Helmand was the next best option, even if it was less vital. . . . The consequences were profound: By devoting so many troops to Helmand instead of Kandahar, the U.S. military squandered more than a year of the war.14

When inter-Service politics interferes with U.S. national security objectives, it is a matter of grave concern.

Affecting actual operations is the most severe effect of inter-Service politics, but it appears to be a rare occurrence. Much more common is the effect inter-Service politics has on the day-to-day running of the Pentagon, especially acquisition, where few observers would claim jointness has made much headway. Though Goldwater-Nichols attempted to reform the administrative side of the Defense Department as well as the operational, it was less successful. Inter-Service politics remains a potent force. For instance, a team from the Institute for Defense Analyses stated, “we found no instance in which the [Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System (the military’s joint requirements generating)] process significantly altered any solution originally proposed by a military service.”15 Requirements in turn have been cited as the primary cause for cost growth, and even irrelevancy, in acquisition programs, suggesting inter-Service politics lies at the heart of the administrative problems within the Department of Defense.

Maybe the presence of inter-Service politics is not so bad, and nothing needs to be done. After all, the Services represent hundreds of years of tradition and, for the most part, have achieved U.S. national security objectives. But the presence of inter-Service politics does undermine two popular theories: First, jointness has successfully integrated the four Services into an almost unified fighting force and achieved efficiency and commonality through the administrative and acquisition systems. Yet the presence of strong inter-Service politics suggests that jointness has served more as cover to allow the Services to remain dominant in their traditional roles and missions without fear of encroachment. And second, it suggests that the Services offer their unique paradigms of war to compete for who can best achieve U.S. national security objectives. Yet instead of encouraging competition, inter-Service politics seems to have created a form of collusion among the Services despite their distinct strategic paradigms, and—as in the case of Afghanistan—that collusion may even affect operations.

At the least, we should stop pretending that jointness has fundamentally eroded Service political power and the Services serve as independent checks on each other. By questioning the platitudes that obscure operational and administrative choices, more salient factors such as cost, Servicemembers’ lives, and national security objectives can better inform policymakers’ decisions.

At the most, those in the uniformed military should more openly acknowledge their parochial concerns and either argue that their parochial perspective better achieves U.S. national security objectives than others’ perspectives or abandon them. The Secretary of Defense and his staff should consider inter-Service politics the primary problem facing U.S. defense and look to weed out its clouding of policy choices. And the President and Congress should consider whether structural reform is needed to change the bargaining advantages that create today’s inter-Service politics.

Today, the United States enjoys operational commanders with more authority than ever before to assemble and wield a joint force. Once selected, the combatant commanders represent national authority, not their parent Service. But even in this area of the greatest advance in jointness, inter-Service politics still intrudes. Though each of our combatant commanders has been an accomplished individual who has served his country well, he has also represented the underlying inter-Service politics that characterizes U.S. national defense. In other areas with less progress toward diminished Service political power, inter-Service politics looms even larger, creating many of the outcomes bemoaned so often. Until the U.S. military can truly be considered as a whole force, and not as distinct and separate baronies, U.S. national security will suffer. JFQ

R. Russell Rumbaugh is Director, Budgeting for Foreign Affairs and Defense, and Senior Associate at The Stimson Center, Washington, DC.

Notes

- C. Kenneth Allard, Command, Control, and the Common Defense (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990), 84–85.

- Rebecca Grant, “Why Airmen Don’t Command,” Air Force Magazine, March 2008.

- “Army Brass Losing Influence,” Associated Press, June 15, 2007.

- Ronald H. Cole et al., The History of the Unified Command Plan: 1946–1993 (Washington, DC: Joint History Office, Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, 1995), 11.

- Bernard Trainor, “Now Chiefs Fight for Command Nobody Wanted,” The New York Times, July 22, 1988.

- Jack Dorsey, “Marine Expected to Win Top Post with Atlantic Command,” The Virginian-Pilot, August 26, 1994.

- The latter two eras could be combined and called the joint era and it would still be an analytically descriptive distinction from the traditional era. But the extra division highlights the development of the changes and the acceleration under Secretary Rumsfeld.

- David Kaiser, “The General in His Labyrinth,” Los Angeles Times, September 23, 2001.

- Andrew R. Hoehn, Albert A. Robbert, and Margaret C. Harrell, Succession Management for Senior Military Positions: The Rumsfeld Model for Secretary of Defense Involvement (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2011), 23.

- Elaine Grossman, “Rumsfeld Set to Shake Up Leadership at Two Key Combat Commands,” Inside Defense, May 13, 2004.

- Cole et al., 4.

- Performing a Chi-square test with three degrees of freedom, each period, respectively, has a p-value of 0.681, 0.392, 0.908, and 0.828. No period is statistically significant compared to the null hypothesis.

- Hoehn, Robbert, and Harrell, 8.

- Rajiv Chandrasekaran, “Obama’s troop increase for Afghan war was misdirected,” The Washington Post, June 22, 2012. Excerpt from Little America: The War within the War for Afghanistan (New York: Knopf, 2012), 64–66.

- Gene Porter et al., The Major Causes of Cost Growth in Defense Acquisition, IDA Paper P-4531 (Alexandria, VA: Institute for Defense Analyses, December 2009), ES-11.