DOWNLOAD PDF

In late 2016, the United States has four major national security interests in South Asia. Three of these are vital security interests with more than a decade of pedigree. They will require new administration policies and strategy to prevent actions that could gravely damage U.S. security: a major conventional war between India and Pakistan, the return of global terrorist safe havens in the region, or the proliferation of nuclear weapons or materials into the hands of America’s enemies. The challenge will be “to keep a lid” on the potential for a major terrorist strike of the U.S. homeland emanating from South Asia or from a major interstate war that could risk nuclear fallout, involvement of China, the loss of nuclear material to terrorists, or a combination of all three. A fourth objective is relatively new, but rising in importance. It requires the new administration to pursue a flexible strategy and proactive but patient security initiatives that enable the responsible rise of an emerging American security partner, India, in a manner that supports U.S. security objectives across the Indo-Pacific region without unintentionally aggravating the Indo-Pakistan security dilemma or unnecessarily stoking Chinese fears of provocative encirclement.

South Asia will not be a glamour portfolio for the incoming U.S. administration’s security team in January 2017, but it will be one of top-five importance. Critical U.S. national security interests are at stake that can be compromised gravely should the South Asia security portfolio be misappreciated or improperly managed. South Asia will require nontrivial defense expenditure and a focused, cohesive security framework advancing four major U.S. national security interests during the period from 2017 to 2020.

Running from Afghanistan in the northwest to Sri Lanka in the southeast, South Asia includes the second most populous country in the world, India, and the sixth most populous one, Pakistan. It is the only region in the world where two independent nuclear weapons states with major security disagreements border each other—India and Pakistan—and sits astride a third—China. Pakistan and India have a seemingly intractable border security dilemma that has produced four general wars and two near-wars since 1947. India and China have an equally vexing, unresolved border demarcation and territory dispute involving 133,000 square kilometers of ground that precipitated a month-long interstate war between them in late 1962.1 South Asia also is plagued by an increasingly deadly mixture of local, regional, and international terrorist organizations, some state-sponsored and others, such as al Qaeda, with a global span and aspirations.

Historically South Asia has been a region of certain distraction for U.S. security interests and defense resources. Since World War II, Washington has aimed to minimize its security profile and defense role in the region. But it has found itself drawn into expensive and lengthy military ventures there. Despite the successive efforts of Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama to withdraw American military forces, the persistence of international terrorist organizations across the Afghanistan-Pakistan region, the fragile nature of the security situation within Afghanistan, and the highly unstable political and security situation in Pakistan have kept the United States substantively engaged into 2016.

As the Cold War gave way to the war on terror in defining American security interests with Pakistan and Afghanistan, those same security interests in India evolved, too. Throughout the Cold War, America pursued a wary-to-hostile relationship with India guided by a fundamental mistrust of India’s Cold War nonalignment posture, especially after New Delhi inked a 1971 Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation with Moscow.2 U.S. mistrust slowly gave way after 1991 as India began a deliberate move away from the defunct Soviet bloc and toward a market-based economy and greater connectivity with the modernized Western world.

The United States has four major national security interests in South Asia. Three of these are vital security interests with more than a decade of pedigree. The fourth is relatively new, but rising in importance.3

First, the incoming administration will be faced with the growing complexities associated with the decades-old, vital counterterrorism (CT) interest of preventing any return to the region of a terrorist group safe haven—especially one in Afghanistan and Pakistan—from where acts of catastrophic global terrorism against the homeland or American interests abroad might be planned and facilitated. Return of an al Qaeda safe haven is of special concern. The new administration will confront a second vital interest: the increasingly difficult challenge of trying to reduce the risks from nuclear weapons proliferation within the region and the potential loss of nuclear weapons material to those with aims to use that material there and beyond. The administration also will inherit a third vital interest, the decades-old security interest of trying to prevent a fifth major general war between Pakistan and India. Mitigating the risks to these three vital U.S. national security interests requires a proper and balanced U.S. military and intelligence presence in Afghanistan along with a sustained, albeit somewhat reduced, U.S. CT partnership with Pakistan focused on verifiable transactional outcomes.4

The next administration will face a fourth major (but not vital) interest: it must actively manage India’s rise as an international security stakeholder. India’s emerging military strength and diplomatic confidence best assist America’s important national interest of constraining China’s use of military might in any manner that would threaten the territorial integrity or sovereignty of its neighbors, or that would hamper free trade, liberal commerce, human rights or the peaceful resolution of grievances in the Indo-Pacific region. American strategy to realize this national security interest should expand upon already accelerating bilateral defense and security initiatives, and, at the same time, it should encourage growing Indian bilateral security activities with long-time U.S. defense partner states in the Asia-Pacific region.

Vital Interest 1: Reducing the Risks of War on the Subcontinent

The United States has a historic, albeit underappreciated, vital national security interest in preventing a major interstate war between India and Pakistan. The disruption of trade and commerce as well as the loss of life from such a conflagration would be severe in the region and ripple across the globe. The consequences would multiply infinitely if either antagonist chose to use even a fraction of its nuclear arsenal in the fight, or if China, Pakistan’s 40-year security ally against India, were to directly engage in the hostilities. Worse yet, the potential for terrorist acquisition of nuclear weapons increases greatly in the event of their deployment onto a chaotic wartime battlefield. At a minimum harm to the U.S. homeland would come from economic and ecological fallout.

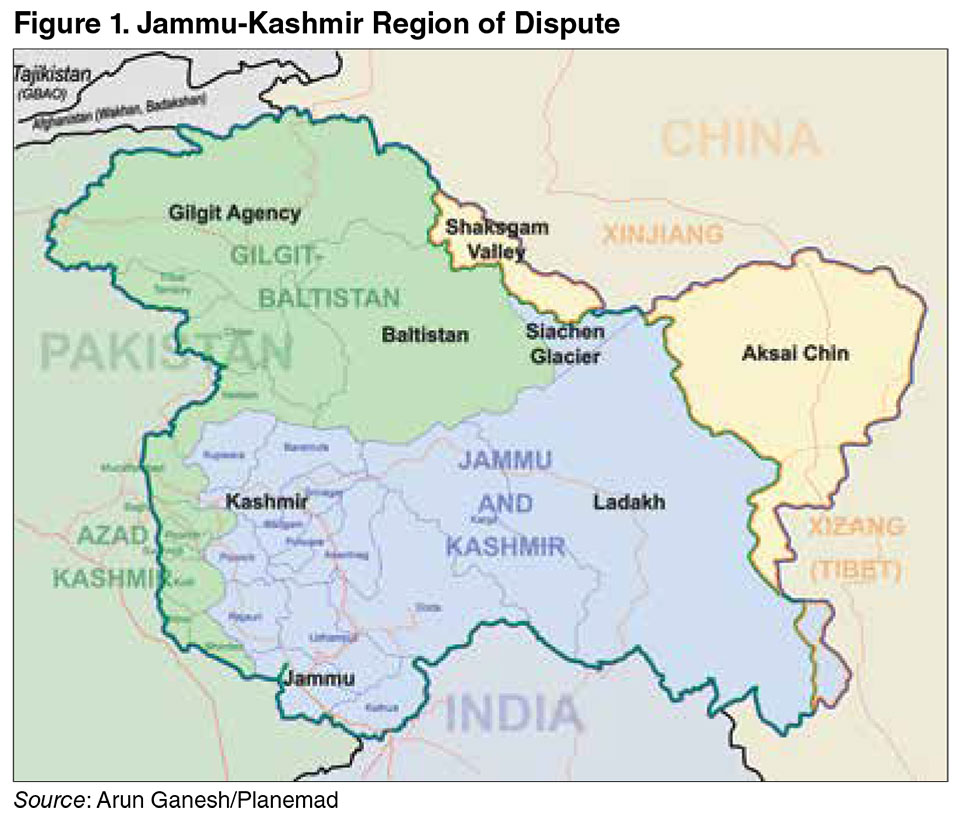

Neither India nor Pakistan wants the certain and massive disruption from such a nation-on-nation war and some in India predict that the circuit breakers in place would prevent a major clash.5 Yet despite frequent declarations of a desire to remain at peace, India and Pakistan have fought four major wars between 1947 and 1999, and nearly came to blows in 2001–2002 and in 2008.6 The 1947–1948 war over Jammu-Kashmir ended indecisively, with that region remaining in dispute between the two nations today (see figure 1).

The 1965 Indo-Pakistan war, which began with subconventional and conventional military activity in Jammu-Kashmir, ended without a clear victor while featuring the largest single clash of armored and air forces witnessed since 1945. The 1971 war began as ugly civil strife in what was then East Pakistan and concluded with Indian military intervention, the defeat of a 90,000-man Pakistani army, and the establishment of the sovereign nation of Bangladesh—stripping away half of Pakistan’s population and one-third of its land mass. The short, sharp 1999 war in the Kargil district of Jammu-Kashmir was the fourth formal war fought between the two antagonists. It was fought under the nuclear umbrella after both Pakistan and India tested nuclear weapons successfully in 1998.

Islamist terrorist strikes in the Indian Parliament in December 2001 and against multiple venues in Mumbai, India, in November 2008—both of which India blamed on the Pakistani state—brought India and Pakistan to the brink of major interstate war once again. In each of these near-miss incidents, India stepped back from a major conventional retaliatory attack against Pakistan after close consultation with American political and military officials.7 Significant American military presence in the region (in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and environs) and unparalleled American leadership access the key civilian and military decisionmakers on both sides of the security divide helped avert a fifth dramatic conflagration.

Escalating Indo-Pakistani animus during 2014–2016 and growing military capabilities assure that the new U.S. administration will be challenged to sustain the peace. The spark for a general Indo-Pakistan war could come from at least three separate sources. Islamist terrorism strikes inside India like those of 2001 or 2008 could again serve as the catalyst for miscalculation leading to major conventional or nuclear war. The government of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, a Hindu nationalist one, has made it clear that it would not be compelled to show the restraint of its predecessor governments should terrorism with suspected Pakistani origins again occur in India.8

Military-on-military clashes between Pakistani and Indian forces along the disputed Line of Control (LOC) in Jammu-Kashmir could, like in 1947 and 1965, lead to such a conflagration.9 The number and severity of cross-LOC direct and indirect fire incidents rose steadily during 2014–2016.10 In early 2016, militants presumed from the Pakistan-resident, Islamist terrorist group Jaish-e-Mohammed stormed Pathankot Indian Air Force Base in Jammu-Kashmir, killing at least seven Indian security personnel and signaling that Pakistan-based militant groups remain willing and perhaps enabled by Pakistan military and intelligence to derail attempts at normalization of relations between national civilian leaders.11 The deadly cross-LOC exchanges also demonstrate how longstanding tensions in Jammu-Kashmir can erupt into stability-threatening military exchanges between the two nuclear armed adversaries.

An escalating proxy war between India and Pakistan in Afghanistan is a third possible catalyst for general war. India and Pakistan treat influence in Afghanistan as a zero-sum game. Islamabad believes that India has established increasingly effective political and economic influence there, believing that Afghans collude with the Indian national intelligence agency (the Research and Intelligence Wing) to weaken Pakistan from within.12 Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence Agency supports the Afghan Taliban and affiliates as a security proxy counterweight. The potential for Afghanistan to become a catalyst for major interstate war was demonstrated in an early January 2016 attack by Afghan Taliban elements on the Indian consulate in the north Afghan town of Mazar-i-Sharif.13 Like the suspected Jaish-e-Mohammed militant attack into Pathankot Indian Air Base days earlier, this strike by a Pakistan-affiliated jihadist group was perceived by many in India as a proxy attack aimed to aggravate India and disrupt any prospects of reduced tensions or a normalized relationship between India and Pakistan.14

New Delhi preferred not to provoke Pakistan while the prospect of security and stability generated by the United States and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in Afghanistan was present. Nonetheless, India has longstanding enmity toward the Afghan Taliban and a silent resolve to see that it never again rules from Kabul or governs sufficient space in Afghanistan to become a conduit for anti-Indian terrorist activities.15 As Western security forces stand down across Afghanistan, India has proffered more direct lethal support to Afghan security forces. In late 2015, India began offering more overt offensive weapons support to the Afghan air force, “gifting” it with four Russian-made Mi-25 “Hind D” attack helicopters for the first time.16

New Delhi also has been expanding and extending its military and intelligence footprint at locations in Tajikistan that can be used to provide logistical, medical, equipment, and intelligence support for an Afghan government fight against the Afghan Taliban or other Pakistani militant proxies.17 New Delhi will support Afghan government efforts to remain sovereign and to safeguard Indian personnel and investments in Afghanistan. It also is setting the diplomatic conditions in Iran and the military-intelligence access arrangements in Tajikistan necessary to support organized proxy resistance should the Afghan government suddenly collapse under the weight of Pakistani-abetted insurgency.18

The means for deadly warfare between India and Pakistan have been growing for more than a decade. India’s increasing military spending and its evolving conventional offensive warfare doctrine contribute to this increasing lethality and instability. India has become the world’s largest arms importer, accounting for 14 percent of global international arms imports from 2009 to 2013.19 India is expected to spend more than $130 billion on arms imports between 2014 and 2020 to upgrade its deteriorating weapons stock.20 Its modernization efforts put at risk critical components of Pakistan’s conventional defenses.

Ever since its frustrating inability to rapidly mobilize forces against Pakistan during the 2001–2002 Indo-Pakistan crisis, India has been slowly updating its offensive conventional military doctrine into one known as “Cold Start.”21 In concept, Cold Start would enable a critical mass of conventional Indian military forces to strike Pakistan in a punitive manner within 48 hours in the event of irregular militia or terrorist provocation.22 Cold Start remains in 2016 an Indian military aspiration rather than a reality. But its impact on Pakistan’s defense psyche has been profound.23 Cold Start caused Pakistan to reshape its nuclear weapons arsenal toward one usable for both deterrence and warfighting.24

Since 2006, Pakistan’s nuclear weapons arsenal has grown dramatically and its capabilities have become ever more oriented toward assured survival and short-range, accurate use in a battlefield warfighting scenario.25 In 2008, Pakistan had an estimated 70–90 nuclear weapons, roughly equivalent to the 60–80 operational weapons estimated for India.26 By early 2009, Pakistan began a much more focused effort on smaller plutonium-warhead designs with battlefield capability.27 It also developed short-range warhead delivery capability and increased fissile material production.28 By mid-2012, Pakistan’s half-decade focus on development of nuclear-capable, short-range and cruise missiles had doubled its number of different nuclear missile warhead delivery systems from four to eight, with three of the four newest delivery systems capable of operating in the short ranges necessary for tactical battlefield delivery29 (see table30).

|

Table. Pakistan’s Growth in Mid- and Short-Range Nuclear Weapons Delivery Systems

|

|

Aircraft

|

Mid-Range Ballistic Missiles

|

Short-Range Ballistic Missiles

|

Cruise Missiles

|

|

F16 A/B (1998) 1,600 kilometers

|

Ghuari (2003)

1,200+ kilometers

|

Shaheen-1 (2003) 450+ kilometers

|

Babur (2011)

600 kilometers

|

|

Mirage Vs (1998) 2,100 kilometers

|

Shaheen-2 (2011) 2,000+ kilometers

|

Ghaznavi (2004)

400 kilometers

|

Ra’ad (2012)

350+ kilometers

|

|

|

|

Abdali (2012)

180 kilometers

|

|

|

|

|

Nasr (2014)

60 kilometers

|

|

It is hard to disentangle the difference between Pakistani tactical nuclear capabilities that are robust enough to signal India of its intent to fight a limited nuclear war in response to an Indian conventional incursion into Pakistan from those capabilities that can actually execute a nuclear attack.31 But there are many sobering clues that suggest Pakistan is resolved to use tactical nuclear weapons in the event of a major clash with India.32

The incoming U.S. administration will face the ongoing challenges of trying to educate Pakistan about the counterproductive nature of tactical nuclear weapons and dissuading Pakistan from continuing down a path of reliance upon battlefield nuclear weapons use as its means to deter a major Indian conventional military strike.

Vital Interest 2: Prevent Reset of International Terrorist Haven in the Region

South Asia will remain a top-tier location for international terrorist organizations seeking safe haven from which to launch catastrophic global attacks against U.S. and Western interests. Standing U.S. CT strategy applied to South Asia aims at preventing al Qaeda’s return to safe haven, denial of any other Salafi jihadist group successor access to unfettered sanctuary, and U.S. assistance to partner-nation capabilities to counter terrorist group activities.33 The enduring challenge for U.S. CT strategy in South Asia is to prevent a reset of a safe haven for international terrorist outfits in Afghanistan and western Pakistan.34

Bowed but unbroken from the U.S.-led ground force and drone attack “surge” during 2009–2013 into Afghanistan and Pakistan, many Salafi jihadist group leaders remain in the region, intermixed with jihadist outfits that transit Central Asia and Iran, waiting for the right moment to regenerate sanctuary in what they believe to be an ideal location from which to manage global jihad.35 In his September 2014 announcement of al Qaeda of the Indian Subcontinent, al Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri prominently praised the Afghan Taliban mujahideen, telling all Salafi jihadist groups in South Asia to fully resource the Afghan Taliban-led effort to reestablish a Salifist emirate in Afghanistan.36 At the same time, a growing array of South Asian–based jihadist groups have been infesting eastern Afghanistan under pressure from a 2014–2015 Pakistani military offensive against terrorists in its North Waziristan border province. Many in the remaining leadership of al Qaeda complicit groups such as Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan, Tehreek-e-Nafaz-e-Shariat-e-Mohammadi, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, the East Turkmenistan Movement, and others have established new operational nodes in Nuristan, Kunar, and Nangarhar provinces in Afghanistan.37

The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) is also a terrorist player in eastern Afghanistan and western Pakistan.38 However, ISIL-Khorasan, as it calls itself, remains small in number, with inspiration but no direct material support from ISIL in Iraq or Syria and little traction when compared to the dozens of Salafi jihadist outfits in the Afghanistan-Pakistan region with solid ties to al Qaeda.39 ISIL-Khorasan’s fate notwithstanding, Afghanistan and Pakistan will remain highly contested spaces for bruised but unrepentant international jihadist organizations.

Since assuming the major role in fighting the insurgency and localized terror groups in January 2015, the 352,000-man strong Afghan National Security and Defense Forces (ANSDF) has struggled against a Taliban resurgence in Afghanistan’s south, its east, and in Kabul itself. In the south and east, Afghan security units have been challenged to secure hard-won U.S./NATO territory contested during the surge fights of 2009–2011.40 In its December 2015 semi-annual report to Congress, the Pentagon admitted that despite ANSDF abilities to consistently retake major ground lost to the Taliban, the overall security situation in Afghanistan had deteriorated, indicating a robust and resilient insurgency.41

The unmistakable growth of Taliban power across southern and eastern Afghanistan in 2015–2016 carved out space for precisely the kind of international terrorist training safe haven that the United States swore to prevent.42 Al Qaeda reportedly established two new terrorism training camps in Kandahar Province, one of which covered nearly 30 square miles. A joint U.S.-Afghan special operations attack raided these camps in the fall of 2015, reportedly killing 100 terrorists in training and wounding 50 more.43 But this episode confirmed the continuing challenge of inhibiting the return of terrorism safe havens in Afghanistan absent a more robust U.S. military intelligence and operational presence.

In recognition of these great and growing challenges in the CT struggle in South Asia, President Obama extended the U.S. military mission in Afghanistan for a longer time and at a larger level of American troops than previously announced.44 In his fall 2015 announcement, Obama promised to maintain some 9,800 U.S. military forces in Afghanistan through most of 2016, tapering to about 5,500 troops by early in 2017. Pentagon officials also indicated that American forces will retain bases of operation beyond Kabul: in Bagram Air Field, at Kandahar, and in Jalalabad.45 These announcements leave it to the next administration to decide on an appropriate U.S. military footprint thereafter.

The incoming administration also will be left to determine the terms of its CT relationship with Pakistan. Enduring although troubled, U.S.-Pakistan collaboration has continued since 2001 against selected regional and international terrorist organizations. The Obama administration, as the Bush administration before it, used a direct support program for Pakistani military, paramilitary, and law enforcement CT activities. American financial support for Pakistani military CT efforts largely consists of a reimbursement program for CT expenditures by the Pakistani military known as Coalition Support Funds (CSF).46 U.S. military CSF dispersed to Pakistan from 2002 to 2015 totaled almost $13 billion.47 Over the same period, indirect support for Pakistan’s military and intelligence services totaled $7.6 billion, and economic-related aid to Pakistan linked to U.S. CT objectives totaled some $10 billion more.48 Pakistan continues to view U.S. compensation and assistance sums as insufficient for its disproportionate losses as “a victim of terrorism,” seeking full reparation for what it contends to be more than $52 billion dollars in physical damages and lost economic activity in its 15-year-old fight of “America’s War on Terror.”49

Despite its 2014–2015 Zarb-e-Azb offensives against the anti-Pakistan Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan and selected international terrorist groups in North Waziristan, Pakistan’s military-intelligence organizations have not broken ties with many longstanding jihadist outfits viewed as beneficial to its state security mission. Chief among these many groups are Lashkar-e-Tayibbah and the Afghan Taliban.50 The incoming administration is likely to see a continuation of the Pakistani national security narrative in the years 2017–2020: CT cooperation against selected Salafi jihadists terrorist groups while protecting those deemed as most essential to Pakistan’s existential battle against real and perceived threats from India.51

The U.S. record of success in fighting terrorist actors in South Asia with Pakistan as an ally is not entirely positive. Yet the record of CT success without Pakistan’s participation during the period 1992–2001 is much worse. The delicate and dangerous situation calls for some form of continuing U.S. military engagement with Pakistani military headquarters in Rawalpindi, albeit at a reduced level, rather than a total cutoff of CT support or military-to-military interactions championed by some.52

The new administration should commit to provide the ANSDF with sufficient direct operational support in the key counterinsurgency capabilities these units inherently lack and will continue to lack through at least 2020: aeromedical casualty evacuation, aerial troop transport to crisis areas, timely heavy indirect fire support from air and artillery, rapid and reliable logistical resupply, and reconnaissance and intelligence support down to brigade and regimental levels.53 The 2016 U.S. military presence in Afghanistan still does too little in support of the ANDSF and has insufficient operational or strategic intelligence assets to independently monitor the increasingly negative interplay of Indian and Pakistani proxy agents or to track the ever-evolving cross-border terrorist milieu. A proper post-2016 residual American military presence should be composed of 20,000 personnel, not 9,800 or 10,800. It should feature much more intelligence capability. This kind of a commitment would not be inexpensive. It would likely cost U.S. taxpayers about $20 billion a year in direct military costs and another $3 to $4 billion a year in indirect costs to pay for sustainment of the ANDSF.54 But this would be less than a $10 billion increase for a capable force from the $15 billion spent in 2015 for the sustainment of an under-resourced and insufficiently capable one scheduled to fall to 5,500 troops in late 2016.55

Across the border, a prudent policy moving forward would sustain U.S.-Pakistan CT collaboration with annual CSF authorities of up to, but not exceeding, $750 million per year, along with sustained economic-related support authority of up to $500 million a year and another $300 million a year in broader security assistance programs.56 These amounts would not make the Pakistani military and intelligence services end their unhelpful relationships with Salafi jihadist militant outfits. However, the sums would help sustain U.S.-Pakistani dialogue in both military-to-military and civilian-to-civilian forums and keep open the possibilities for critical terrorist information exchange and—if needed—crisis response.

Vital Interest 3: Constrain Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons on the Subcontinent

Although related to those above, this is a distinct U.S. vital regional security interest. India and Pakistan have been vexing to American nuclear nonproliferation interests for more than 40 years. India and Pakistan acquired nuclear weapons despite American and international blandishment and warnings. Both withstood international military and economic sanctions after their announced testing of nuclear weapons in 1998. But in the mid-2000s, their nuclear weapons trajectories diverged. India, championed by the George W. Bush administration as a responsible steward of its nuclear weapons arsenal, gained exceptional status as a nuclear weapons state in 2008. Pakistan remained an international nuclear pariah without formal recognition for its nuclear arsenal, which continues to grow and is feared to be at growing risk from loss to a terrorist organization.57

For most of the past 60 years, American Presidents have been strong advocates of preventing the spread of nuclear weapons to countries beyond the original “nuclear weapons states club”: the United States, Soviet Union (Russia), China, Great Britain, and France.58 Since 1972, most American administrations have been verbal proponents of halting the growth of standing nuclear weapons arsenals or reducing their size despite the massive growth of the U.S. nuclear arsenal during the height of the Cold War. From at least 1992 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, American Presidents also have focused on preventing the spread of nuclear weapons to international criminal organizations and terrorist groups.59

The Obama administration’s comprehensive approach to nuclear nonproliferation differed in form from the pragmatic flexibility pursued by the administration of George W. Bush in South Asia.60 Under President Bush, the United States in September 2001 lifted the nuclear-related sanctions imposed on both India and Pakistan following their nuclear weapons tests in 1998.61 The lifting of sanctions against Pakistan was a quid pro quo for an urgently required U.S.-Pakistan partnership in the American-led war on terror and imminent American attacks against the Taliban and al Qaeda in Afghanistan. The near-simultaneous lifting of sanctions against India set the conditions for something even bigger: a pathbreaking India-U.S. civil nuclear deal. Announced as an aspiration in July 2005, negotiated and signed by 2006, and ratified in 2008, this India-U.S. Civil Nuclear Agreement (or 123 Agreement) moved India from international nuclear outcast to insider.62 It also worried China and upset Pakistan.

China fretted over the deal because of its obvious pathway for greater Indian strategic interaction with the United States. Beijing protested, briefly, that the deal unfairly excluded Pakistan, arguing that Islamabad should be accorded a similar exception. When the United States and other nations countered that Pakistan had a highly checkered record of safeguarding its nuclear weapons technology, Beijing backed off.63 But China then sold Pakistan additional civil nuclear reactors in what was seen as a violation of nuclear sanctions against Pakistan, but what Beijing argued was an allowed “grandfathered exemption” to its 2004 accession to the Nuclear Suppliers Group non-transfer prohibitions for Pakistan.64 India, as does the rest of the world, worries that these new reactors will augment Pakistan’s ability to harvest nuclear weapons fuel for its expanding nuclear weapons arsenal.

The new administration will have three major nonproliferation concerns with Pakistan. First, the continuing overall growth of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons arsenal is historic and destabilizing. In 2015 Pakistan had a nuclear weapons stockpile of 110 to 130 warheads, up from an estimated 90 to 110 in 2011.65 This gave Pakistan the world’s sixth largest nuclear weapons arsenal—only behind the arsenals of the original six pre–Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty nuclear weapons states. Pakistan’s presumed mastery of the processes for building lighter, smaller tactical nuclear weapons (miniaturization) means that it now has the potential to produce up to 15 tactical nuclear systems a year, which is forecast to grow to an additional 30–35 per year from 2020.66

Second, Pakistan continues to develop smaller nuclear warheads and more accurate short-range delivery systems for these warheads, clearly setting the conditions for their use in a battlefield scenario. This increases both the risk of nuclear weapons use in the event of a general Indo-Pakistani war and the risk of accidental loss or theft of these more widely dispersed nuclear devices.

Finally, domestic radicalization and proliferating Islamist terrorist and violent extremist groups in Pakistan put it at serious risk of national fragmentation and severe domestic violence. In these extreme but entirely plausible scenarios, the risks of terrorists or rogue international actors acquiring nuclear weapons or material grows precipitously.67

The new U.S. administration should continue CT engagement as well as offers of assistance to Pakistan to safeguard its nuclear arsenal. At the same time it should sustain recent U.S. practices of discouraging Pakistan from its nuclear weapons growth trajectory with information sessions and earnest discussion about the dangers from and counter-productivity of tactical nuclear weapons.68 There can be no illusions that Pakistan will be easily dissuaded from its present nuclear weapons course. At the same time, Pakistan is nowhere near ready for consideration as a civil nuclear deal (123 Agreement) partner. Yet discussions about where and how far Pakistan must go to be viewed as a responsible player offer more promise for eventual reversal of Islamabad’s dangerous course than does a policy of isolation.

There also are concerns with India’s nuclear weapons nonproliferation standards, although not as acute as those concerns with Pakistan. Three stand out. First, when compared to Pakistan, India’s nuclear weapons safeguards are not independently verified and feared to be somewhat weak despite Indian insistence to the contrary.69 While treading gently so as not to excite a negative Indian response, the new administration should encourage greater Indian transparency. Second, India has a longstanding policy of “no first use” (NFU) of nuclear weapons, meaning that India will not use nuclear weapons first, but if its opponents do, then India’s response would be overwhelming.70 Incoming Prime Minister Modi ruled out change of the NFU policy in August 2014, but some in the Indian military community continue to agitate for a revision away from massive retaliation and toward “punitive” retaliation if struck first.71 Any such change in Indian nuclear use policy would be unhelpful for strategic stability between India and Pakistan and between India and China. The new American administration should take every opportunity to encourage the Indian government to sustain its NFU doctrine.

Finally, the nuclear ballistic missile competition between Pakistan and India is close to spurring a serious arms race. Both have flight-tested ballistic missiles with short- and longer range delivery capability for nuclear warheads. Pakistan’s ballistic arsenal can now reach targets in all of India. India’s can now reach targets throughout China. India and China have the technical know-how to place multiple warheads atop some of their missiles and to deploy limited ballistic missile defenses.72 Any serious move by India to pursue even a limited ballistic missile defense (BMD) against Pakistan’s growing nuclear arsenal—as some in its hawkish minority now advocate—would have major ripple effects. Growth in Indian BMD coupled with testing of multiple reentry vehicle nuclear warhead technology could be seen as threatening by China, igniting an undesirable and dangerous nuclear missile versus antiballistic missile arms race.73 In addition, investments by India and Pakistan in sea-based nuclear weapons delivery capabilities are increasing and create greater uncertainty and instability in the region.74 American nonproliferation interests require that the incoming administration conduct an earnest dialogue with the Indian government about the advisability of restraint in these areas.75

Given the multivariate challenges to nuclear weapons nonproliferation in Pakistan and India, the new administration will be best advised to pursue prudent pragmatism as its regional nonproliferation approach.

Major Interest 4: Nurture the Rise of India as a Strategic Partner

In early 2012, the Obama administration announced its “Rebalance to the Asia-Pacific Strategy.”76 By the summer of 2012, senior American defense officials like then–Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta and then–U.S. Pacific Command Commander Admiral Samuel Locklear made it clear that this region included India—speaking openly about the rebalance focusing on the Indo-Asia-Pacific region.77 With these clarifications of geographic intent, the U.S. rebalance to the Indo-Pacific incorporated its decade-old emerging strategic engagement with India.

The warming relations between the two countries had an economic baseline. But they also had a security and defense component influenced by India’s growing financial ability to purchase American military hardware and informed by India’s potential to be a defense partner in balancing against the possible rise of a militarily assertive and anti–status quo China.78 From 2004 to 2008, the Bush administration set the conditions for this growing security collaboration.79

The Obama administration significantly extended these Bush administration advances and simultaneously linked a decade of bilateral U.S.-Indian defense and security interactions with the U.S. rebalance strategy when it signed the Joint Strategic Vision for the Asia-Pacific and Indian Ocean Region (JSV) with India in January 2015.80 The U.S.-India JSV put on paper the basic framework for U.S.-Indian security cooperation, emphasizing the common interests between Washington and New Delhi in assuring that the entire Indo-Pacific region remains one where the following conditions prevail:

- maritime security is safeguarded

- freedom of navigation and overflight remains unfettered, including in the South China Sea

- all parties choose peaceful means for the resolution of territorial and maritime disputes

- the interests of peace, prosperity, and stability are underpinned by a common commitment to human rights.81

Although it will not become a military ally in the foreseeable future, India is a good bet to become a valuable security partner of the United States and other East Asian countries against an aggressive and anti–status quo China. While India remains a strong trading partner with China—and relies upon this partnership to meet its ambitious annual gross domestic product growth goals—India’s geopolitical issues with China make it plausible that India could become adversarial with China at some point in the future.82

Geopolitical strains between India and China are evident in five major areas. First, India and China have a large and seemingly intractable land border dispute over 133,000 square kilometers of contested land83 (see figure 2). They fought a short, sharp war over these borders in 1962. Despite decades of halting diplomatic talks, the borders remain unresolved.84 Second, even though India recognized Chinese territorial sovereignty over Tibet in the 1950s—with the caveat that China respect the cultural, religious, and social uniqueness of Tibet—New Delhi has been aggravated by Chinese treatment of Tibet, offering the Dali Lama safe haven in the late 1950s and supporting the Lama’s ownership of his Buddhist successor selection. India views the growing presence of Chinese military units and construction outfits there to be menacing.

Third, India chafes over China’s decades-long role as an enabler of Pakistan’s military. From the 1960s, China has been the main channel for information and equipment necessary to advance Pakistan’s heavily embargoed nuclear power program and its nuclear weapons activities.85 For the past two decades, China has been a key conduit of information to Pakistan on the design of ballistic missiles and, more recently, tactical nuclear weapons.86 Almost all security observers in India are wary that China would become party to a two-front war with India should any combination of the three come to blows.

Fourth, India worries greatly about Chinese maritime activities in the Indian Ocean. Many Indians believe that ongoing Chinese efforts at acquiring deep water berthing ports for commercial activities there are actually a step toward building a “string of pearls” to encircle India.87 In 2015 and 2016, the government of Prime Minister Modi moved to assert its soft-power tools, courting neighboring countries such as Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, the Maldives, and the Seychelles with lucrative commercial port alternatives to those from China. At the same time, more Indian voices advocate the use of hard power against Chinese maritime encroachment in the Indian Ocean maritime space.

Finally, India has great and growing concerns about Chinese respect for freedom of navigation on the high seas. New Delhi has been worried about Chinese aggressive claims and its threats of force to gain control over the important international navigation space in the South China Sea. India has been a critic of Chinese actions and acted as a friend to the states of Southeast Asia who challenge Chinese hegemonic encroachment. India has sent its warships into waterways astride Vietnam and China, and in the vicinity of disputed South China Sea islands. India should be expected to continue with these unilateral actions challenging China should Beijing not desist in its assertive South China Sea activities.88

Since 2010, India has participated in more annual military exercises with U.S. military forces than with any other nation in the world.89 It will remain difficult for the new U.S. administration to dramatically accelerate the pace or the scope of India’s bilateral engagement with America. India’s historic preference for strategic autonomy remains strong and will inhibit any formal alliance. This means that New Delhi will partner with Washington in areas of common security and economic interest where China’s actions do not align.

Anticipating the certainty of challenges with the pace and the depth of U.S.-Indian bilateral security progress in the years from 2017 to 2020, the incoming U.S. administration might best think in terms of how it can help facilitate deeper Indian bilateral engagements with Washington’s other security partners in the Indo-Pacific region. This approach—one involving “third party facilitation” of an enhanced web of Indian security partnerships across the wider Pacific region—should feature three areas for administration attention: military technology, multilateral military doctrine, and regional training partnerships.

The new administration should conduct a review of standing U.S. export constraints on certain military technology transfers. As an example, India may become interested in purchasing Japanese submarines with quiet propulsion technology.90 Existing U.S. export controls on this technology might constrain Japan’s ability to sell or license it to India. The U.S. critical technologies standards could—and should—be updated to allow for this kind of a mutually beneficial exchange.

The incoming administration should be creative in its approaches to military training and doctrinal development with India. In the area of doctrine, the United States might work with India to establish regional partnership forums to discuss the way ahead for shared doctrine in the areas of military cyberspace, military operations in space, military operation of remotely piloted vehicles, and other emerging defense areas. Indian officials have expressed interest in becoming a “training node” for Southeast Asia and Pacific states’ militaries seeking to become interoperable in activities ranging from disaster management and relief to coastal waterway security and beyond.91 The United States might look at creative ways to encourage regional hub training centers for multilateral military interactions.

At the end of the day, India’s rise as a hedge against malevolent Chinese behavior in the Indo-Pacific region uniquely supports a vital U.S. security interest. If the incoming administration can work around Indian security peculiarities patiently, it can shape an Indo-Pacific Ocean security architecture featuring India, Japan, Australia, South Korea, and others capable of limiting malign Chinese behaviors and of safeguarding the standards and norms of the post–World War II economic and security architecture in the Far East—and at a bearable cost to U.S. taxpayers.

Major Implications for U.S. Security Policy in South Asia

Absent a truly unexpected event or an unlikely set of circumstances, the United States will have four major national security interests in South Asia from 2017 to 2020. Three of these interests are vital and will require administration policy and strategy to prevent actions that could gravely damage U.S. security. The challenge is “to keep a lid” on the potential for a major terrorist strike of the U.S. homeland emanating from South Asia—or, from a major interstate war that could risk nuclear fallout, involvement of China, the loss of nuclear material to terrorists, or a combination of all three. A fourth objective requires flexible administration strategy and activities to enhance the natural trajectory of an emerging security partner, India, in a manner that supports U.S. security objectives in the Indo-Pacific region.

The incoming administration must work to inhibit the potential for major conventional or nuclear war between India and Pakistan that might embroil China. Success in this objective will require a mixture of diplomatic acumen and properly positioned U.S. military forces in countries that will host them—like Afghanistan.

Simultaneously, the new administration will need to invest wisely in policies and activities that prevent any return of safe havens for international terrorist outfits in Afghanistan or western Pakistan. To attain this challenging objective, Washington policymakers must do a thorough review of the insufficient U.S. force structure in Afghanistan, increasing the number and properly balancing the composition of U.S. forces, while maintaining a proper basing structure throughout Afghanistan including locations in Kabul, Bagram, Kandahar, and across the East and Southeast of the country. The incoming administration also should continue to pursue CT cooperation with Pakistan, reframing it in a manner that continues the beneficial aspects at a reduced cost and that sustains important military-to-military interactions and intelligence access.

The incoming administration also will be challenged to inhibit the proliferation of nuclear weapons on the subcontinent. But a pragmatic and discriminate nuclear nonproliferation approach could achieve the most important regional aims. Limiting the potential for nuclear weapons use in a major Indo-Pakistani war is a paramount objective. Continuing multilateral dialogue to educate Pakistan about the counterproductive nature of battlefield nuclear weapons use is a key element. The new administration should work to assure Pakistani openness to nuclear weapons security best practices and exchanges and to validation of the security of Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal. Enabled by a proper balance of U.S. intelligence assets in Afghanistan, the administration also should seek to anticipate major risks for loss or compromise of Pakistani nuclear weapons and materials, resolving to arrest any such compromise before it can occur.

Finally, the incoming administration has an unparalleled opportunity to extend and enhance India’s ongoing rise in the regional and international security system. It should steadily expand on already growing bilateral defense initiatives in the areas of military hardware purchases, military exercises and training, and military administration dialogues. It also should abet third-party facilitation of Indian bilateral security activities with longstanding American defense partners in the Asia-Pacific region, especially Japan, South Korea, and Australia, in support of the current Indo-Pacific security and economic order and as a hedge against potential Chinese challenges to that order.

The first three vital regional U.S. national security interests share one common theme: the need to establish a proper U.S. military and intelligence presence in Afghanistan. Properly sizing—and paying for—an American military presence in Afghanistan into 2020 enables key elements of the top three U.S. national security interests: preventing major Indo-Pakistani war emanating from a proxy spiral from inside Afghanistan, militating against the return of any globally capable terrorist combination to safe haven in Afghanistan or Pakistan, and thoroughly tracking and—if necessary—responding to the loss or theft of nuclear weapons material in Pakistan by terrorists or criminals.92

A properly scoped American military presence in Afghanistan combined with a reduced but sustained U.S counterterrorism partnership with Islamabad also helps keep the Pakistan military-intelligence complex engaged in the regional fight against traditional and emergent terrorist organizations with global reach. Sustained U.S.-Pakistan CT interaction also helps to enable military-diplomatic access to Pakistan military leaders in order to monitor and/or help arrest dramatic escalation in a future India-Pakistan military crisis or militate against an implosion of security or stability in Pakistan itself.

South Asia should rank among the top-five focus areas for new administration national security priorities. It will continue to engage vital U.S. security interests in CT, nuclear nonproliferation, and the deterrence of major interstate war between nuclear weapons nations. It will also involve a major interest in managing the rise of India in the shadow of China. The costs to national treasure for sound management of these vital security interests should come to about 20,000 U.S. troops and $25 billion in Afghanistan, 500 to 1,000 U.S. troops and about $2.5 billion in U.S. CT and other aid in Pakistan, and a robust and growing military-to-military exercise and exchange presence with India. The expense will not be trivial, but the national security benefits will be great.

Notes

1 Bruce Riedel, JFK’s Forgotten Crisis: Tibet, The CIA and the Sino-Indian War (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 2015).

2 Shri Ram Sharma, India-USSR Relations, 1947–1971: From Ambivalence to Steadfastness, Part-1 (New Delhi: Discovery Publishing House, 1999); Andrew Small, The China-Pakistan Axis: Asia’s New Geopolitics (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 9–16.

3 There are several other relatively new opportunities for increased American security engagement across South Asia between 2017 and 2020. Burma (Myanmar) and Sri Lanka are continuing to emerge from lengthy periods of international sanction for human rights abuses and are anxious for greater direct American security engagements. Nepal is ready for greater American assistance with security-sector reform. Bangladesh continues to request more engagement in U.S. military naval and special operations forces exercises along with continuing counterterrorism financial and maritime-shore security equipment support. Worthy of American national security attention as these opportunities are, none of them rise to the threshold of major American security interests in South Asia. See Murray Hiebert, “Engaging Myanmar’s Military: Carpe Diem Part II,” CSIS.org, September 5, 2013; David Brunnstrom, “U.S. General Eager for Myanmar Engagement, Awaiting Policy Decision,” Reuters, December 8, 2015; Department of State Fact Sheet, “U.S. Relations with Sri Lanka,” February 25, 2015, available at <www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/5249.htm>; Kadira Pethiyagoda, “Sri Lanka: A Lesson for U.S. Strategy,” The Diplomat, August 26, 2015, available at <http://thediplomat.com/2015/08/sri-lanka-a-lesson-for-u-s-strategy/>; Bruce Vaughn, Nepal: Political Developments and U.S. Relations, R44303 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, December 4, 2015), 1–3; Jenna Bernhardson, “U.S. Security Assistance in Bangladesh,” Department of State Dipnote, October 21, 2014; Kevin Chambers, “U.S., Bangladesh Armed Forces Complete CARAT 2015,” U.S. Navy News Service, October 5, 2015, available at <www.navy.mil/submit/display.asp?story_id=91356>.

4 This chapter identifies three vital and enduring U.S. national security interests in South Asia. The author’s assessment of these as vital—meaning that a failure to meet them would lead to significant harm to the American homeland—concurs with and extends similar assessments found in James Dobbins et al., ed., Choices for America in a Turbulent World (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2015), 108–110, 113–119; and “Threats to U.S. Vital Interests: Where Are U.S. Interests Being Threatened Around the World?” 2016 Index of U.S. Military Strength (Washington, DC: Heritage Foundation, 2016), available at <http://index.heritage.org/military/2016/assessments/threats/>.

5 For example, see Bharat Karnad, Why India Is Not a Great Power (Yet) (London: Oxford University Press, 2015).

6 See Stephen P. Cohen, Shooting for a Century: The India-Pakistan Conundrum (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 2013), 88–117; C. Christine Fair, Fighting to the End: The Pakistan Army’s Way of War (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 136–153.

7 Polly Nayak and Michael Krepon, U.S. Crisis Management in South Asia’s Twin Peaks Crisis (Washington, DC: Stimson Center, 2006); Polly Nayak and Michael Krepon, The Unfinished Crisis: U.S. Crisis Management After the 2008 Mumbai Attacks (Washington, DC: Stimson Center, February 2012).

8 “Everything Will Be Fine Soon: PM Modi on Kashmir Ceasefire Violations,” The Times of India (Mumbai), October 8, 2014, available at <http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Everything-will-be-fine-soon-PM-Modi-on-Kashmir-ceasefire-violations/articleshow/44713666.cms>; George Perkovich and Toby Dalton, “Modi’s Strategic Choice: How to Respond to Terrorism from Pakistan,” The Washington Quarterly 38, no. 1 (Spring 2015), 23–45.

9 This scenario is cited as a feasible one leading to general Indo-Pakistani war in Michael E. O’Hanlon, The Future of Land Warfare (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 2015), 109–116.

10 Violating the standing ceasefire agreement, units from Pakistan’s Punjab Rangers and its X Corps exchanged artillery, mortar, rocket, and small arms fire with elements of the Indian Army Northern Command in 60 incidents from July 2014 to November 2015. Both sides engaged in deadly violations. Their exchanges reportedly resulted in the deaths of 22 Indian soldiers, 19 Pakistani soldiers, and nearly 90 civilians, with dozens more military personnel wounded and hundreds of civilians wounded and displaced from homes near the border. See Kamran Yousaf, “Pakistan, India Agree to Stop Ceasefire Violations at Working Boundary,” The Express Tribune (Karachi), September 12, 2015; Perkovich and Dalton, 23–26.

11 Niharrika Mandhana and Aditi Malhorta, “Indian Forces Hunt for Militants After Deadly Attack on Air Force Base,” Wall Street Journal, January 3, 2016, available at <www.wsj.com/articles/indian-forces-hunt-for-militants-after-deadly-attack-on-air-force-base-1451820057>; Navjeevan Gopal, “Pathankot Attack: Parrikar Admits ‘Gaps’ in Security, Says Terrorists Used ‘Pak-made’ Equipment,” The Indian Express (Uttar Pradesh), January 5, 2016.

12 See Umar Farooq, “Afghanistan-Pakistan: The Covert War,” The Diplomat, January 1, 2014.

13 “Reports: Indian Consulate in Afghan City Attacked,” Radio Free Europe–Radio Liberty, January 3, 2016, available at <www.rferl.org/content/afghanistan-indian-consulate-attacked/27465427.html>.

14 “Pakistani Non-State Actors Backed by State Responsible for Pathankot Attack, Says Parrikar,” FirstPost.com, March 1, 2016, available at <www.firstpost.com/world/pakistani-non-state-actors-backed-by-state-responsible-for-pathankot-attack-says-parrikar-2650334.html?utm_source=FP_CAT_LATEST_NEWS>; “Pakistan Military Officers behind Indian Consulate Attack: Afghan Police,” HindustanTimes.com, January 13, 2016, available at <www.hindustantimes.com/india/top-afghan-official-says-pakistan-military-officers-behind-indian-consulate-attack-in-mazar-e-sharif/story-tpMK8zHcCmKiv4HY8FNBDM.html>.

15 Gareth Price, India’s Policy Towards Afghanistan (London: Chatham House, August 2013), 3, 9.

16 “Afghanistan Turns to India for Military Helicopters,” Dawn (Karachi), November 6, 2015, available at <www.dawn.com/news/1217859>; “Taking Ties to the Next Level—India Gifts MI-25 Helicopters to Afghanistan,” MotivateMe.in, December 24, 2015, available at <http://motivateme.in/taking-ties-to-the-next-level-india-gifts-mi-25-helicopters-to-afghanistan/>.

17 “Farhkhor Air Base: India’s Foreign Military Base,” Indian Aerospace and Defence News, December 27, 2015, available at <http://iadnews.in/2015/12/farkhor-air-base-indias-foreign-military-base/#.VoKlKf1IiM8>; “Tajikistan Entertains Indian Offer for Air Base,” SilkRoadReporters.com, July 17, 2015, available at <www.silkroadreporters.com/2015/07/17/tajikistan-entertains-indian-offer-for-air-base/>; Joshua Kucera, “India’s Central Asia Soft Power,” The Diplomat, September 3, 2011, available at <http://thediplomat.com/2011/09/indias-central-asia-soft-power/>.

18 For a discussion of India’s upgrades to its military and intelligence access in Tajikistan, see Rajeev Sharma, “India’s Anyi Military Base in Tajikistan is Russia-locked,” Russia and India Report, October 26, 2012, available at <http://in.rbth.com/articles/2012/10/26/indias_ayni_military_base_in_tajikistan_is_russia-locked_18661.html>; “India, Tajikistan to Step Up Counter-Terrorism Cooperation,” Business Standard (New Delhi), September 11, 2014, available at <www.business-standard.com/article/pti-stories/india-tajikistan-to-step-up-counter-terrorism-cooperation-114091101203_1.html>.

19 Siemon T. Wezeman, “International Arms Transfers,” in SIPRI Yearbook (Stockholm: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, 2013), available at <www.sipri.org/yearbook/2014/05>.

20 India is focused on modernization of its Soviet-era carrier-based aircraft systems, its attack aircraft, its unmanned aerial vehicles, its antitank missiles, and its air mobility. See Rama Lakshmi, “India Is the World’s Largest Arms Importer: It Aims to Be a Big Weapons Dealer, Too,” Washington Post, November 16, 2014, available at <www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/india-is-the-worlds-largest-arms-importer-it-aims-to-be-a-big-weapons-dealer-too/2014/11/15/10839bc9-2627-4a41-a4d6-b376e0f860ea_story.html>.

21 The detailed historical review of the 2001–2002 “Twin Peaks” crisis by researchers also suggests that American diplomatic intervention proved a critical inhibitor to conflict escalation in a pattern they found repeated in many respects during the 2008 Mumbai Crisis. See Nayak and Krepon, U.S. Crisis Management; Nayak and Krepon, The Unfinished Crisis.

22 For a detailed description and analysis of India’s Cold Start doctrine, see Walter C. Ladwig III, “A Cold Start for Hot Wars? The Indian Army’s New Limited War Doctrine,” International Security 32, no. 3 (Winter 2007/2008), 158–190; also see Nitin Gokhal, “India Military Eyes Combine Threat,” The Diplomat, January 17, 2012, available at <http://thediplomat.com/2012/01/17/india-military-eyes-combined-threat/>. For more on Indian limitations in attaining its doctrinal aims, see Shashank Joshi, “The Mythology of Cold Start,” New York Times blog, November 4, 2011, available at <http://india.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/11/04/the-mythology-of-cold-start/>. For an alternative name to Cold Start, proactive doctrine, first observed in 2012–2013 Indian military writings, see Dhruv Katoch, Looking Beyond the Proactive Doctrine (New Delhi: Centre for Land Warfare Studies, September 2013), available at <http://strategicstudyindia.blogspot.com/2013/09/looking-beyond-proactive-doctrine.html>.

23 See Feroz Hassan Khan, Eating Grass: The Making of the Pakistani Bomb (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2012), 381–382.

24 As observed by Indian national security adviser Shiv Shankar Menon in August 2012, India’s civilian leadership perceives Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program to be aimed at reducing India’s conventional military advantage, not for deterrence against nuclear weapons first use: “The possession of nuclear weapons has, empirically speaking, deterred others from attempting nuclear coercion or blackmail against India . . . unlike certain other nuclear weapons states, India’s weapons were not meant to redress a military imbalance or some perceived inferiority in conventional terms.” Quoted in “India Faced N-blackmail Thrice: NSA,” Hindustan Times (New Delhi), August 21, 2012.

25 Jaganath Sankaran, “Pakistan’s Battlefield Nuclear Policy: A Risky Solution to an Exaggerated Threat,” International Security 39, no. 3 (Winter 2014/2015), 118–151; Tom Hundley, “Pakistan and India: Race to the End,” Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, September 5, 2012, available at <http://pulitzercenter.org/reporting/pakistan-nuclear-weapons-battlefield-india-arms-race-energy-cold-war>.

26 Hans M. Kristensen and Robert S. Norris, “Pakistan’s Nuclear Forces, 2011,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 67, no. 4 (2011), 83, available at <http://bos.sagepub.com/content/67/4/91.full.pdf+html>.

27 Joby Warrick, “Nuclear Experts Say Pakistan May Be Building a 4th Plutonium Reactor,” Washington Post, February 9, 2011.

28 Cited in “Pakistan Successfully Test Fires Hatf-9 Nasr Missile,” The Nation (Lahore), May 29, 2012, available at <www.nation.com.pk/pakistan-news-newspaper-daily-english-online/national/29-May-2012/pakistan-successfully-test-fires-hatf-9-nasr-missile>.

29 Kristensen and Norris, 93.

30 Table from Thomas F. Lynch III, Crisis Stability and Nuclear Exchange Risks on the Subcontinent: Major Trends and the Iran Factor, INSS Strategic Perspectives 14 (Washington, DC: NDU Press, November 2013), 8.

31 On the dynamic of signaling versus credibility in relation to U.S. military historical experience with battlefield nuclear weapons and the applicability to Pakistan, including his conclusion that, “rather than improving Pakistan’s deterrence of India, these weapons hold only the promise of lowering the nuclear threshold and guaranteeing a larger nuclear exchange by both sides once they are used,” see David O. Smith, The U.S. Experience with Nuclear Weapons: Lessons for South Asia (Washington, DC: Stimson Center, 2013), especially 31–41. Also see Akhilesh Pillalamarri, “Confirmed: Pakistan Is Building ‘Battlefield Nukes’ to Deter India,” NationalInterest.org, March 24, 2015, available at <http://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/confirmed-pakistan-building-battlefield-nukes-deter-india-12474>. On the degree to which Pakistan’s ambiguous and uncertain relationship with Islamic militants and terrorist organizations acting in Jammu-Kashmir and India render it a dubious “unitary actor” in the construct of nuclear weapons deterrence theory, see George Perkovich, The Non-Unitary Model and Deterrence Stability in South Asia (Washington, DC: Stimson Center, November 13, 2012), 8–16.

32 See Zachary Keck, “Watch Out, India: Pakistan Is Ready to Use Nuclear Weapons,” NationalInterest.org, July 8, 2015, available at <http://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/watch-out-india-pakistan-ready-use-nuclear-weapons-13284>; interview with a senior Pakistani Strategic Plans Directorate official by author in Washington, DC, February 2011; Maria Sultan, “Cold Start Doctrine and Pakistan’s Counter- measures: Theory of Strategic Equivalence-III,” The News (Karachi), September 30, 2011, available at <www.thenews.com.pk/TodaysPrintDetail.aspx?ID=70218&Cat=2>; Vipin Naran, “Pakistan’s Nuclear Posture: Implications for South Asian Stability (Cambridge, MA: Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, January 2010), available at <http://belfercenter.ksg.harvard.edu/publication/19889/pakistans_nuclear_posture.html>; interview with former Pakistani nuclear weapons program leader by author in Washington, DC, November 2012.

33 National Strategy for Counterterrorism (Washington, DC: The White House, June 2011), 2–3, 8–13. Also see Thomas F. Lynch III, The 80 Percent Solution: The Strategic Defeat of bin Laden’s al-Qaeda and Implications for South Asian Security (Washington, DC: New America Foundation, February 2012).

34 Terrorism and radicalism in Bangladesh continue to pose a threat to foreigners—and often Westerners—residing there. There is some evidence that international terrorism facilitators transit Bangladesh. See “U.S. Updates Security Alert in Bangladesh,” DhakaTribune.com, October 18, 2015, available at <www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/2015/oct/18/us-updates-security-alert-bangladesh>; The Role of Civil Society in Countering Radicalization in Bangladesh (Dhaka: Bangladesh Enterprise Institute, September 2014). In addition, India remains at moderate risk from attempts by al Qaeda of the Indian Subcontinent to radicalize its Muslim youth for local terror activities and from the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) to leverage sympathetic Indian Muslims for social media support of its global recruiting quest. See Elizabeth Bennet, “A Comeback for al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent?” Foreign Policy Journal, May 12, 2015, available at <www.foreignpolicyjournal.com/2015/05/12/a-comeback-for-al-qaeda-in-the-indian-subcontinent/>; Praveen Swami, “Al-Qaeda Chief Ayman al-Zawahari Announces New Front to Wage War on India,” Indian Express (New Delhi), September 4, 2014, available at <http://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-others/al-qaeda-leader-ayman-al-zawahiri-announces-formation-of-india-al-qaeda/>. But these counterterrorism issues pale in comparison to those in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

35 See Lynch, The 80 Percent Solution, 810.

36 See “Al-Qaeda Chief Zawahiri Launches al-Qaeda in South Asia,” BBC News Asia, September 4, 2014, available at <www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-29056668>; “Full Text of Al Qaeda Chief Ayman al-Zawahiri’s Audio Message,” TheDailyStar.net, available at <www.thedailystar.net/upload/gallery/pdf/transcription-zawahiri-msg.pdf>.

37 See “Pakistan Wants Afghanistan to Hand Over Maulana Fazlullah,” The Express Tribune (Karachi), October 21, 2014, available at <http://tribune.com.pk/story/454861/pakistan-wants-afghanistan-to-hand-over-maulana-fazlullah/>; Bill Roggio, “U.S. Military Continues to Claim al Qaeda Is ‘Restricted’ to ‘Isolated Areas of Northeastern Afghanistan,’” The Long War Journal, November 19, 2014, available at <www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2014/11/us_military_continue.php>; Zahir Shah Sherasi, “U.S. Drone Strike Kills 7 on Pak-Afghan Border,” Dawn (Karachi), September 14, 2014, available at <www.dawn.com/news/1131869/us-drone-strike-kills-7-on-pak-afghan-border>.

38 ISIL is the official name used by the U.S. Government, originating at the U.S. National Counter Terrorism Center (NCTC), for the Salafi jihadist terrorist group led by Abu Bakr al Baghdadi, headquartered in Raqqa, Syria, and Mosul, Iraq, and alternatively known as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and the Islamic State (IS). Although many of the sources and citations in this chapter for the group reference ISIS or IS, ISIL is used to remain consistent with the official U.S. nomenclature. See “Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL),” Counter Terrorism Guide, available at <www.nctc.gov/site/groups/aqi_isil.html>.

39 Thomas F. Lynch III, The Islamic State as Icarus: A Critical Assessment of an Untenable Threat (Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, October 2015), 14–16, 21–25, available at <www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/theislamicstateasicarus.pdf>; Bill Roggio, “U.S. Drone Strike Kills Mufti of Islamic State Khorasan Province,” The Long War Journal, October 15, 2015, available at <www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2015/10/us-drone-strike-kills-mufti-of-islamic-state-khorasan-province.php>; Michael R. Gordon, “ISIS Building ‘Little Nests’ in Afghanistan, U.S. Defense Secretary Warns,” New York Times, December 18, 2015.

40 See “Afghan Troops Battle Mass Taliban Assault in Helmand,” BBC News Asia, June 15, 2014, available at <www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-28012340>; Rod Nordland and Taimoor Shah, “Afghans Say Taliban are Nearing Control of Key District,” New York Times, September 6, 2014, available at <www.nytimes.com/2014/09/07/world/asia/afghanistan.html?_r=0>; Ratib Noori, “ANSF Regain Control of Sangin,” Tolo News, October 12, 2014, available at <www.tolonews.com/en/afghanistan/16711-ansf-regain-control-of-sangi>; David Jolly and Taimoor Shah, “Afghan Province, Teetering to the Taliban, Draws In Extra U.S. Forces,” New York Times, December 13, 2015.

41 Enhancing Security and Stability in Afghanistan: A Report to Congress in Accordance with Section 1225 of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year (FY) 2015 (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, December 2015), 16–24, available at <www.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/1225_Report_Dec_2015_-_Final_20151210.pdf>. Also see Elizabeth Williams, “Taliban Summer Offensive Shows Increasing Capability,” Institute for the Study of War, September 2014, available at <www.understandingwar.org/sites/default/files/Taliban%20violence%20report_0.pdf>; Eric Schmitt and David Sanger, “As U.S. Focuses on ISIS and the Taliban, Al Qaeda Re-emerges,” New York Times, December 29, 2015, available at <www.nytimes.com/2015/12/30/us/politics/as-us-focuses-on-isis-and-the-taliban-al-qaeda-re-emerges.html?ref=world&_r=0>; Jawad Sukhanyar and Mujib Mashal, “Bombings Near Kabul Airport Add to String of Attacks Around Afghan Capital, New York Times, January 4, 2016, available at <www.nytimes.com/2016/01/05/world/asia/bombings-near-kabul-airport-add-to-string-of-attacks-around-afghan-capital.html?_r=0>.

42 By late 2015, experts estimated that the Afghan Taliban controlled 40 administrative districts across Afghanistan and contested another 39, including almost all of those in southern Helmand Province and most in southern Kandahar Province. Bill Roggio, “Taliban Controls or Contests Nearly All of Southern Afghan Province,” The Long War Journal, December 21, 2015, available at <www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2015/12/taliban-controls-or-contests-nearly-all-of-southern-afghan-province.php>.

43 Bill Roggio and Thomas Joscelyn, “U.S. Military Strikes Large al Qaeda Training Camps in Southern Afghanistan,” The Long War Journal, October 13, 2015, available at <www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2015/10/us-military-strikes-large-al-qaeda-training-camps-in-southern-afghanistan.php>; Enhancing Security and Stability in Afghanistan, 23–24.

44 Previously, the Barack Obama administration had announced that it would withdraw all but a small U.S. Embassy–based military contingent, estimated at about 1,000 troops, from Afghanistan by the end of 2016. See Julie Pace, “Obama Extends U.S. Military Mission in Afghanistan into 2017,” Associated Press, October 15, 2015, available at <http://bigstory.ap.org/article/fa394db4a9f24815ab44c573e26be8dc/officials-obama-keep-troops-afghanistan-beyond-2016>.

45 Lucas Tomlinson, “Pentagon Pushing for Long-Term U.S. Presence at Bagram, as Taliban Gain Ground,” FoxNews.com, December 28, 2015, available at <www.foxnews.com/politics/2015/12/28/pentagon-pushing-for-long-term-us-presence-at-bagram-as-taliban-gains-ground.html>. Mark Mazzetti and Eric Schmitt, “Obama’s ‘Boots on the Ground’: U.S. Special Forces Are Sent to Tackle Global Threats,” New York Times, December 27, 2015.

46 Coalition Support Funds (CSF) normally take a year from Pakistani request to American reimbursement. Congress has set limits on the annual maximum amount of U.S. CSF that Pakistan’s military can receive. In fiscal year (FY) 2014, this cap was $1.2 billion; in FY2015 it was $1 billion, with $300 million of that made conditional on Pakistani actions against the Haqqani Network; in FY2016 the congressional cap was $900 million. See Stephen Tankel, “Is the United States Cutting Pakistan Off? The Politics of Military Aid,” War on the Rocks, August 31, 2015, available at <http://warontherocks.com/2015/08/is-the-united-states-cutting-pakistan-off-the-politics-of-military-aid/>.

47 Alan Kronstadt, Pakistan-U.S. Relations: Issues for the 114th Congress, R44034 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, May 14, 2015), 16.

48 Ibid., 16.

49 Figure cited in multiple presentations by senior Pakistani military officials in Washington, DC, during 2015, including by Pakistani Air Chief Marshal Sohail Aman at a National Defense University student presentation, October 7, 2015.

50 This point is made more robustly, if less delicately, in Christine Fair, “Pakistan’s Strategic Shift Is Pure Fiction,” War on the Rocks, August 13, 2015, available at <http://warontherocks.com/2015/08/pakistans-strategic-shift-is-pure-fiction/>.

51 See Stephen Tankel, “Pakistan Militancy in the Shadow of the U.S. Withdrawal,” in Pakistan’s Enduring Challenges, ed. Christine Fair and Sarah J. Watson (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015).

52 Fair, “Pakistan’s Security Shift Is Pure Fiction.”

53 The Afghan National Army had 152 D-30 howitzers in its inventory as of late 2013 and is eventually scheduled to have 204 fielded. It has a reasonable quantity of heavy indirect fire support, but it lacks the ground and air mobility to move these heavy artillery pieces to support infantry in the remote and foreboding territory where most counterinsurgency fighting occurs. See Praveen Swami, “Why India Is Concerned about Supplying Arms to Afghanistan,” FirstPost.com, May 22, 2013, available at <www.firstpost.com/world/why-india-is-concerned-about-supplying-arms-to-afghanistan-800711.html>; Antonio Giustozzi with Peter Quentin, The Afghan National Army: Sustainability Challenges Beyond Financial Aspects (Kabul: Afghan Research and Evaluation Unit, February 2014), 3–6, 17–19, available at <www.ecoi.net/file_upload/1226_1400655058_ana-20issues-20paper.pdf>.

54 For a detailed review of the numbers, functions, and costs of a sufficient residual U.S. military presence, see Thomas F. Lynch III, “After ISIS: Fully Reappraising U.S. Policy in Afghanistan,” The Washington Quarterly 38, no. 2 (Summer 2015), 119–144.

55 See Tom Vanden Brook, “Top U.S. General May Seek More Troops for Afghanistan,” USA Today, December 29, 2015, available at <www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2015/12/29/gen-john-campbell-afghanistan-taliban-isil/78033970/>.

56 These numbers are at the low end of the range of U.S. support to Pakistan in these broad categories from 2010 to 2016. See Kronstadt, 16.

57 Dan Twining, “Pakistan and the Nuclear Nightmare,” ForeignPolicy.com, September 4, 2013, available at <http://foreignpolicy.com/2013/09/04/pakistan-and-the-nuclear-nightmare/>.

58 China is also a member of the pre–Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty nuclear weapons states club, even though Washington tried to prevent Beijing from acquiring nuclear weapons in the 1950s and 1960s. See “Nuclear Weapons: Who Has What at a Glance,” ArmsControl.org, October 2015, available at <www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/Nuclearweaponswhohaswhat>.

59 See National Security Strategy (Washington, DC: White House, February 2015), 11–12, available at <www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/docs/2015_national_security_strategy_2.pdf>; Carl Levin and Jack Reed, “A Democratic View: Toward a More Responsible Nuclear Nonproliferation Strategy,” Arms Control Today, January 1, 2004, available at <www.armscontrol.org/act/2004_01-02/LevinReed>.

60 Theodore Kalionzes and Kaegan McGrath, “Obama’s Nuclear Nonproliferation and Disarmament Agenda: Building Steam or Losing Traction?” NTI.org, January 15, 2010, available at <www.nti.org/analysis/articles/obamas-nuclear-agenda/>; Department of State, “Nuclear Security Summit: Washington, 2010,” available at <www.state.gov/t/isn/nuclearsecuritysummit/2010/>.

61 John Bolton, “The Bush Administration’s Nonproliferation Policy: Successes and Future Changes,” testimony before the House International Relations Committee, March 30, 2004, available at <http://2001-2009.state.gov/t/us/rm/31029.htm>.

62 “The Timeline of the India-U.S. Nuclear Agreement,” The News Minute (Bangalore, Karnataka), February 25, 2015, available at <www.thenewsminute.com/article/timeline-india-us-nuclear-agreement-22957>; “Agreement for Cooperation Between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of India Concerning Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy (123 Agreement), Council on Foreign Relations, August 2007, available at <www.cfr.org/india/agreement-cooperation-between-government-united-states-america-government-india-concerning-peaceful-uses-nuclear-energy-123-agreement/p15459>; C. Raja Mohan, “10 Years of Indo-U.S. Civil Nuclear Deal: Transformation of the Bilateral Relationship Is the Real Big Deal,” The India Express (New Delhi), July 20, 2015, available at <http://indianexpress.com/article/explained/10-yrs-of-indo-us-civil-nuclear-deal-transformation-of-the-bilateral-relationship-is-the-real-big-deal/>; “Joint Statement by President George W. Bush and Prime Minister Manmohan Singh,” press release, Department of State, July 18, 2005, available at <http://2001-2009.state.gov/p/sca/rls/pr/2005/49763.htm>.

63 On the illicit nuclear proliferation activities of Pakistan state scientist A.Q. Khan, see Nuclear Black Markets: Pakistan, A.Q. Khan and the Rise of Proliferation Networks—A Net Assessment (London: International Institute for Strategic Studies, May 2007), available at <www.iiss.org/publications/strategic-dossiers/nbm/nuclear-black-market-dossier-a-net-assesment/pakistans-nuclear-programme-and-imports-/>.

64 Tim Craig, “Outcry and Fear as Pakistan Builds New Nuclear Reactors in Dangerous Karachi,” Washington Post, March 5, 2015, available at <www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/outcry-and-fear-as-pakistan-builds-new-nuclear-reactors-in-dangerous-karachi/2015/03/05/425e8e70-bc59-11e4-9dfb-03366e719af8_story.html>; Chris Buckley, “Behind the Chinese-Pakistan Nuclear Deal,” New York Times, November 27, 2013, available at <http://sinosphere.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/11/27/behind-the-chinese-pakistani-nuclear-deal/?_r=0>.

65 Hans M. Kristensen and Robert S. Norris, “Pakistan Nuclear Forces, 2015,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 71, no. 6 (November 2015), available at <http://thebulletin.org/2015/november/pakistani-nuclear-forces-20158845>.

66 See Shaun Gregory, “Terrorist Tactics in Pakistan Threaten Nuclear Safety,” Combating Terrorism Center Journal 4, no. 6 (June 2011), 4.

67 On the plausibility of extreme violence, national fragmentation, and widespread civil disorder in Pakistan’s future, see Stephen P. Cohen, The Future of Pakistan (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 2011).

68 David O. Smith, The U.S. Experience with Tactical Nuclear Weapons: Lessons for South Asia (Washington, DC: Stimson Center, 2013), available at <www.stimson.org/images/uploads/research-pdfs/David_Smith_Tactical_Nuclear_Weapons.pdf>.

69 M.V. Ramana, “India Ratifies an Additional Protocol and Will Safeguard Two More Nuclear Power Reactors,” International Panel on Fissile Materials blog, July 1, 2014, available at <http://fissilematerials.org/blog/2014/07/india_ratifies_an_additio.html>.

70 Shashank Joshi, “India’s Nuclear Anxieties: The Debate over Doctrine,” Arms Control Association, May 2015, available at </www.armscontrol.org/ACT/2015_05/Features/India-Nuclear-Anxieties-The-Debate-Over-Doctrine>.

71 Gurmeet Kanwal, “India’s Nuclear Doctrine: Need for a Review,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, December 5, 2014, available at <http://csis.org/publication/indias-nuclear-doctrine-need-review>.

72 Michael Krepon, “Deterrence Instability in South Asia,” ArmsControlWonk.com, May 4, 2015, available at <www.armscontrolwonk.com/archive/404605/deterrence-instability-in-south-asia/>.