DOWNLOAD PDF

The effective use of the informational instrument of national power in all

domains, and the use of all the instruments of national power in the cyber

domain, will be a serious and growing challenge for the United States. The

next U.S. President must have a clear understanding of the relationship of

technology, law, and policy in formulating options. Centralized but not

procrustean, leadership at the highest level, providing a clear and rational

delineation of authorities, will be needed to coordinate and effectively employ

U.S. cyber and information capabilities. Internationally, engaging with allies

and partners will be vital to our defense; engaging with adversaries will require

a new understanding of deterrence and counter-espionage in cyberspace.

Domestically, new approaches to public-private partnerships will be key to

addressing threats, preserving civil liberties, and unleashing our potential for

improved governance and expanded commerce.

By any measure, the United States leads the world as a cyber power in

terms of its cyberspace-related leadership and capabilities, research

and development, innovation, and commercialization of leading-edge

hardware and software, as well as more specialized products for military

and scientific applications. This is also true for the world of information.

Without any whole-of-government coordination, the United States produces

and exports the lion’s share of globally consumed television, film,

music, and games, as well as data, information, and knowledge systems.

Its advances in mobile communications and social media have revolutionized

the way the global community communicates, learns, and even

thinks.

With this largely unplanned success has come a series of challenges,

many of which require a more deliberate approach and a national-level

strategic effort with Presidential leadership to resolve. This chapter

provides summary views of many of these challenges and offers recommendations by which the administration

could gain traction over

even the most daunting issues in

the information and cyberspace

domain.

From the perspective of the

Department of Defense (DOD),

the term cyberspace is defined as

a global domain within the information

environment consisting

of interdependent networks of information

technology infrastructures

and resident data, including

the Internet, telecommunications

networks, computer systems, and embedded processors and controllers.1 Protecting this domain is a national priority. It underpins U.S. and

global commerce, governmental and private discourse, innovation, and

creativity. It has evolved into an essential enabler of governance, business,

and personal transactions. It has elevated the impact of information

in all its forms and provides both opportunities for and limitations to the

way we conduct our national security strategy.

The actors with whom the United States must engage (and sometimes

counter) include capable nation-states, criminals, and nonstate actors.

Many of these are not bound by the same norms and restraints that the

United States observes. The complex motives and methods, combined

with a low barrier to entry, heighten the potential for damaging effects

caused by competitor and adversary actions.

The need to ensure that we both leverage the potential of cyberspace

for U.S. national and global advantage and protect our systems and information

to ensure our prosperity and security as a nation demands

a comprehensive, integrated strategy that provides coherence of action

and synchronizes Federal, state, and local initiatives in cooperation with

our partners in industry as well as with foreign governments.

Framing Cyberspace: The Possible, Permissible, and Preferable

Because cyberspace is a domain of near-infinite complexity, we need

models to allow us to build common theoretical frameworks to help us

synchronize our academic research, operational planning, and high-level

policymaking. Nowhere is such a common operating picture more

important than in explaining the relational positions of technology, law,

and policy.

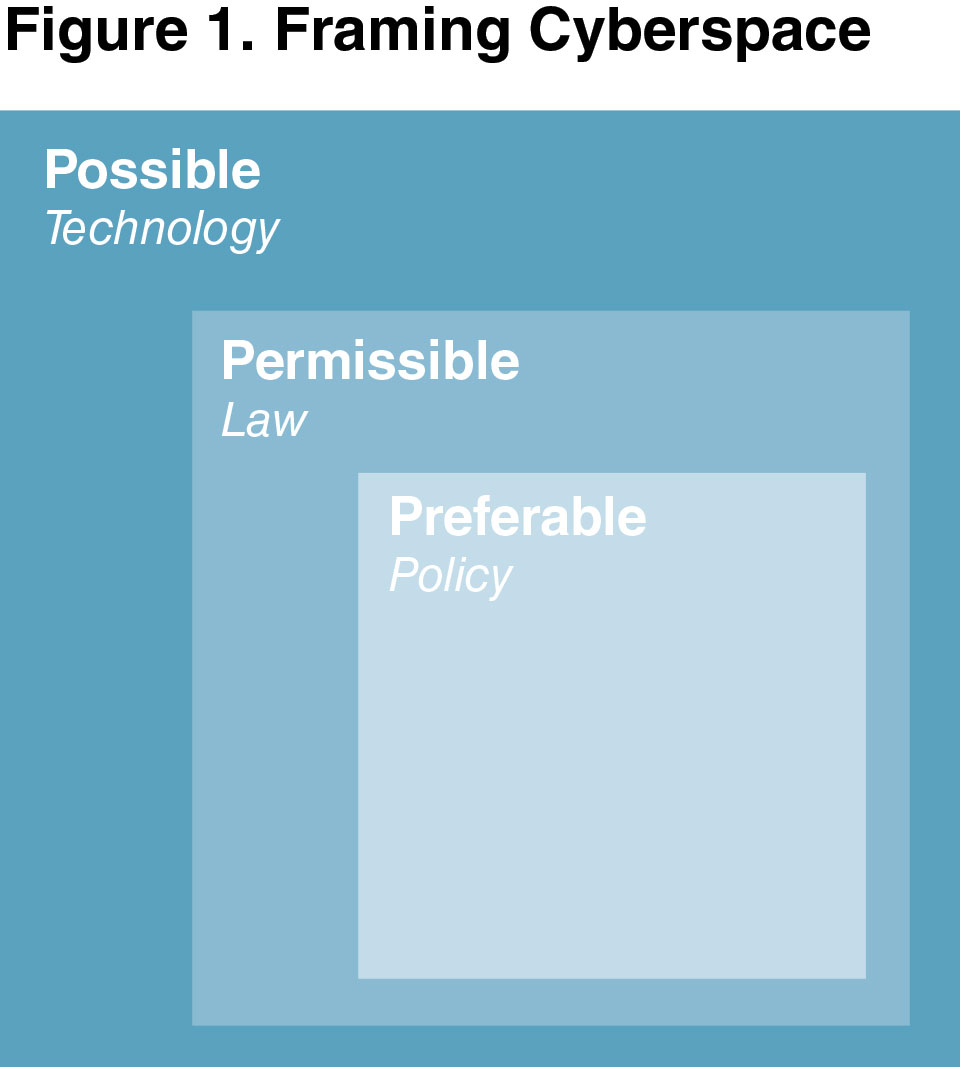

In figure 1, the outermost box represents technology—the range of

the possible. As the largest box, it consists of everything that technologists

have delivered or can deliver without violating the laws of physics.

Some of these options are lawful, some are not; others make good policy

sense, while others do not. To extend the metaphor, the top and sides

of the box can be extended with more time, more money, or smarter

scientists and engineers. The bottom, however, cannot be extended—it

represents those laws of physics and other barriers beyond our control

that limit our expansion to the other three directions.

The intermediate box represents the law—the limits of what is permissible.

Outside this box are options that are technically feasible but

legally impermissible; inside the box is the full range of lawful options

for policymakers to consider. Just as with technology, the top and sides

of this box can be expanded—domestically by an executive order, statute,

or court ruling. Internationally, we can expand (or contract) this

box with treaties or, more often, by concerted changes to state practice

with opinio juris (the stated position that international law requires or

permits a certain action), resulting in a reinforcement of, or change to,

customary international law. But just as with technology, there are virtually

unchangeable aspects of the law. Domestically, the best examples

are fundamental constitutional norms—freedom of speech, or freedom

from unreasonable search and seizure—that are unlikely to be altered,

even through another constitutional amendment. Internationally, we refer

to these near-unchangeable laws as jus cogens norms—prohibitions

accepted by so many states for such a great length of time that only other

jus cogens norms could displace them. Examples include the universal

bans on piracy, slavery, grave war crimes, and genocide. This is not to say

that these crimes do not exist but rather that their historical severity has

rendered them unlikely to ever be legalized. Their most important aspect

is their universal applicability, even in the face of a dissenting state. For

international lawyers, jus cogens norms are the equivalent of the laws of

physics.

The innermost, and smallest, box is policy—the realm of the preferable.

These are the policy options that make the most strategic sense,

aligning desired ends with available means most effectively. They make

the most political sense, whether in response to public opinion, media

coverage, or interest-group or thought-leader positions. They might

be the path of least resistance within a bureaucracy, the least common

denominator position adopted by a coalition of allies, a workable compromise

within a legislature, or an executive’s daring vision. In any case,

they are the product of the political forces operating at the time and

should be derived from the largest possible menu of lawful options. As with the other two boxes, we can imagine three sides that can be moved

with time, money, and political capital, just as we can imagine a fourth

side that cannot be—policy options that are considered so politically

toxic or strategically unfeasible as to be impossible.

Governance Framework and Policy

Multiple partitions abound in the Federal Government’s design, reflecting

the economic and political priorities of the Industrial Age. One effect

is the pile-up of “cross-cutting” issues—particularly those generated

by the disruptive information/digital age—that fail to fit neatly within

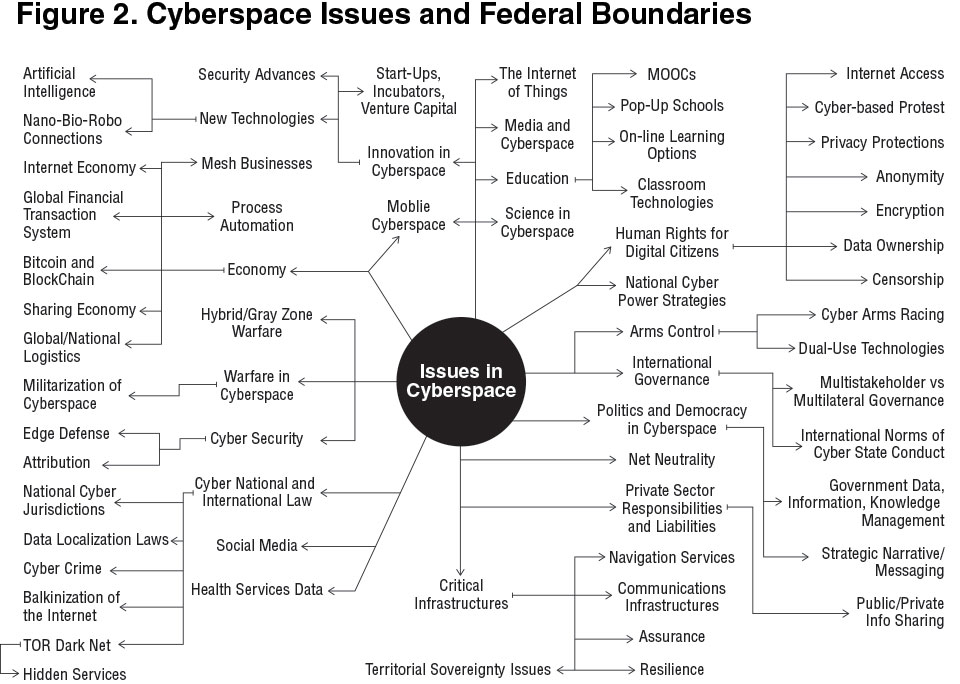

outdated Federal agency/department boundaries. Figure 2 shows examples

of cyberspace issues that run across, over, under, and around these

boundaries.

This leads to costly dysfunctionality. Issues of cyberspace become too

fractured and segregated to fit within the logic of existing department/

agency mission areas. This limits responses to departmental or agency-

specific responsibilities, which rarely consider or incorporate all

the other parts of a cross-cutting issue. The results are solutions with a

higher risk of failure—for example, the persistent failure to share electronic

health records between DOD and the Veteran’s Administration.

Departments and agencies waste resources and duplicate efforts. Bureaucratic

barriers bound Federal work and employees within department and agency authority structures, which lose synergistic value. Moreover,

these arrangements cause unnecessary contestation for resources and arguments

over leadership, spending, and control at the expense of shared

best practice solutions.

Four reform strategies have been attempted thus far: grabbing agency

components to create an Industrial Age–style Department of Homeland

Security, designating lead agencies, appointing “supervisory czars”

over groups of agencies (for example, Director and Office of National

Intelligence), and building lower-level issue-specific fusion centers for

cross-agency information-sharing and coordination. Collectively, these

strategies have generated modest improvements in shared situational

awareness on the cross-cutting issues of cyberspace. They have been

handicapped by a narrow focus, inappropriate appropriations classifications,

and misaligned authorities and responsibilities, leading to continued

duplication of effort, poor exploration of unintended consequences

of policy actions, and constant work to address undiscovered feasibility,

affordability, and utility issues. We offer the following recommendations:

- Map Federal Government relationships within cyberspace writ

large to generate shared situational awareness as the basis for effectively

integrating the executive branch. This map should offer a

dashboard-style real-time presentation of connections, crossovers,

databases, and knowledge sets of the Federal Government and expand

to include commercial, nongovernmental, and international

networks.

- As a first step to fitting the Federal Government for the digital age,

create an empowered and resourced leadership structure in the executive

office with a cyberspace remit (rather than one focused on

e-government or cybersecurity).

- Task this new structure and leadership to launch a “hackathon”-style

initiative to acquire and explore new options for executive branch

network structures that are not dependent on current Federal Government

agency and department boundaries, budgets, and authorities.

- Design a collaborative follow-on strategy with congressional Members

and staffs for identifying legal frameworks for authorizing,

appropriating, and overseeing such networked and adaptive structures.

Reviewing Cyber Authorities

The U.S. Government has not clearly laid out the roles, responsibilities,

and authorities (RRA) of its components for cyberspace operations. As

a result, U.S. actions in cyberspace are nether coordinated nor synchronized,

and resources are not coordinated to reduce inefficiency and unintended

redundancy.

As identified in the 2016 Cybersecurity National Action Plan (CNAP),

the Barack Obama administration’s cyber policy has been based on three

strategic pillars: raising the level of cybersecurity in American public, private,

and consumer sectors; taking steps to deter, disrupt, and interfere

with malicious cyber activity aimed at the United States or its allies; and

responding effectively to, and recovering from, cyber incidents.2 In addition

to the CNAP, areas previously addressed include information-sharing

(Executive Order 136913), improving government information technology

and information security, increasing public cyber awareness and education,

and increasing the size and quality of the military and civilian

cyber workforce. These initiatives are helping to address the tactical and

operational weaknesses of the United States. Unfortunately, what is missing

is a comprehensive framework that clearly articulates the RRA for

Federal, state, and local governments. There are several key documents

that address aspects of this problem, the most important of which are

Presidential Policy Directive (PPD)-20, PPD-21, and PPD-41.4 All address

important shortfalls, but greater synchronization and clearer authorities

and responsibilities are needed. We offer the following recommendations:

- Replace the patchwork of executive branch policies that describe cyber

roles, responsibilities, and, on occasion, authorities with a single

overarching document.

- Ensure specificity and clarity when assigning RRA in cyberspace for

Federal organizations. There are debates about responsibility whenever

agencies have to interpret RRA, which delays collaboration and

hinders the sharing of information. Require rotational assignments

for senior executives to ensure a more complete understanding of

the roles and responsibilities of other Federal agencies.

- Ensure this new document expands upon the framework initially

outlined in PPD-20. Unlike PPD-41, which focuses solely on event

response, the policy must look holistically at cyberspace to include

planning for the building of the cyberspace terrain and how we operate

in that terrain (both offensively and defensively).

- Continue the concept of using lines of effort as introduced in PPD-41.

This format is an easy structure to understand, clearly identifies the

supported and supporting organizations, and will enhance collaboration

among agencies across the range of cyber activities.

- Make the document unclassified. A major issue with PPD-20 is that

it is a top secret document and the vast majority of the workforce

has no idea of its contents—or even its existence. This made it

challenging for the Federal workforce to understand how its organization

fit into the cyberspace architecture. In addition, the private

sector and American people lacked knowledge of U.S. defenses and

cyberspace capabilities.

- Consider creating a Department of Cyber to unify capabilities and

provide leadership. Following the U.S. Coast Guard precedent of

having one of the Armed Forces report to an agency other than DOD,

consider aligning U.S. Cyber Command under this new department.

Engaging the International Community on Internet Governance

The United States must engage the international community regarding

Internet governance to ensure that information in cyberspace remains

free and accessible to U.S. citizens and the global community. Framing

this complex challenge requires understanding the roles that cyber

strategy, policy, regulation, and security play in Internet governance. It

is also important to assess whether our efforts to secure the Internet and

protect information and privacy rights are consistent with overarching

“governing” objectives (that is, information freedom and net neutrality)

and to ensure that our security efforts do not threaten the very liberties

they are intended to protect.

This is not to suggest that U.S. engagement can wait. The pace and

scope of the Internet’s growth and the infinite ways it is evolving (with

economic, political, and social implications) necessitate a deliberate and

decisive engagement. While the Internet has ushered in great societal

benefits, it has also introduced new risks, such as crime, terrorism, and

warfare, that threaten the critical infrastructure and services on which

societies depend. The risk borne by individuals and societies continues

to expand as complex and tightly coupled systems5 such as electrical

power grids, services such as health care, and the emerging “Internet of

things” are increasingly interconnected, moving us from the information

age to a “network society.”6 As with any technology, there are intended

and unintended uses and users. There are some who desire to leverage the Internet to bring local, national, and global services and benefits.7

There are others with nefarious intentions, introducing crime, exploitation,

and terrorism into cyberspace. We offer the following recommendations:

- Map infrastructural Internet components to identify gaps and redundancies

in governance.

- Incorporate cyberspace policies and standards into future bilateral

and multilateral trade agreements to establish and reinforce needed

international cyber norms.

- Forge new ties with a variety of nonstate actors including industry,

nongovernmental organizations, and international organizations

(for example, the International Telecommunications Union, Internet

Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers, and so forth) to

build a coalition of governing actors that share democratic values as

they relate to information and cyberspace.

- Engage the public in this policy formation process, as its understanding

of the benefits and risks associated with the Internet is

key to its future security and resiliency. This can be accomplished

through different forms of public forums.

Measuring Performance in Cyberspace

Performance management has been required of Federal agencies since

passage of the Government Performance and Results Act of 1993. However,

the integration of performance information into agency decisionmaking

is not well advanced.8 Despite efforts by the George W. Bush and

Obama administrations, the Government Accountability Office noted

that reported use of performance information for high-level objectives

did not improve between 2007 and 2013.9 Since cyber is a relatively

new field, cyber performance management is still a fairly undefined term.

During this developmental stage, the cyber world must embrace performance

measures that link organizational strategic goals and objectives

with strategic initiatives in order to assist government agency–level leaders

or executives with organizational decisionmaking.

Traditional information technology (IT) services, those commonly

found under the domain of Federal chief information officers (CIOs), do

have performance metrics. These existing metrics (for example, network

availability, number of trouble tickets resolved) do not address cyber performance management. As a result, organizational cultures inappropriately

place responsibility for gains from cyberspace on technicians alone.

We offer the following recommendations:

- Include a performance management framework for cyber in the next

National Security Strategy (NSS).

- Mandate agency strategies include performance measures that directly

align with the performance management framework in the

NSS.

- Develop performance measures that reflect cyberspace’s impact on

national strategy goals such as national security, civil liberties, and

economic growth.

Deterrence and Offensive Cyber Operations

Cyber deterrence is a critical component of overall strategic deterrence,

but it is far less developed conceptually. Some see a parallel between

nuclear weapons and cyber weapons and posit that nuclear deterrence

models could therefore be usefully applied to cyberspace. One critical

difference is the scalability of cyber weapons, which allows for cyber deterrence

at the operational and tactical levels. The table highlights some

of the differences between nuclear and cyber weapons. These differences

illuminate the need to develop a new model that incorporates the unique

aspects of cyber deterrence.

|

Table. Differences Between Nuclear and Cyber Weapons

|

|

|

Target of Deterrence

|

Development Effort

|

Effects of Use

|

Proliferation

|

Deterrence

|

|

Nuclear Weapons

|

State

|

State-level resources

|

Immediate overt destruction

|

Low

|

Well understood

|

|

Cyber Weapons

|

State Nonstate Individuals

|

Individuals to state, but also self-creating

|

Widely variable breadth, depth, and time

|

High

|

Debatable

|

The target of deterrence needs to believe the deterring state has the

capability to impose an unacceptable cost for an attack, coupled with the

will to use that capability, or the capability to defend against or immediately

recover from an attack, rendering it ineffective. The highly secretive

nature of our offensive cyber capabilities and the many restrictions

placed on their use limit their deterrent effect. Additionally, cyber attacks

are often difficult to trace. This lack of attribution means attackers need

not fear retribution. Finally, leaders who feel vulnerable to retaliation or find an attack to be pointless due to resilience may also hesitate to act

or to escalate.

Cyber weapons are part of a larger arsenal of national power that the

United States could bring to bear to deter or, should deterrence fail, to

defeat our enemies. While cyber weapons may be the most appropriate

means to achieve a specified effect, other sources of national power are

also clearly relevant to both cyber deterrence and cyber operations in

conflict scenarios. We offer the following recommendations:

- Support a sufficiently capable cyber force to ensure a deterrent effect

and, should deterrence fail, to prevail in conflict scenarios.

- Emphasize the essential nature of cyber resilience as a matter of

broad national policy to promote necessary investments in backup

and restoration capabilities, and invest in technologies that make

defensive cyber operations faster and less manpower-intensive, such

as artificial intelligence and big data analytics.

- Direct research on the integration of cyber capabilities into deterrence

theory frameworks.

Advancing Public-Private Partnerships

The loss of critical infrastructure “would have a debilitating impact on

security, national economic security, national public health or safety.”10

The majority (about 85 percent) of critical infrastructure is privately

owned and operated, requiring a public-private partnership to provide

its security.11 Operating alone, the private sector is incentivized by profit

and is averse to liability. This puts the resiliency of national critical infrastructure

at risk.

The current strategy of promoting and facilitating best practices and

information-sharing with the government is necessary but insufficient

to addressing sophisticated threats of organized crime, terrorists, and

nation-states. National interests traditionally handled through law enforcement

or national defense are not aligned with the financial and reputational

interests of the private sector. As the United Kingdom Cyber

Security Strategy states, “Just as in the 19th century we had to secure the

seas for our national safety and prosperity, and in the 20th century we had

to secure the air, in the 21st century we also have to secure our advantage

in cyber space.”12 We offer the following recommendations:

- Propose legislation to accelerate and expand the provisions of the

U.S. Cybersecurity Act of 2015.

- Promote incentives, venues, and opportunities that encourage private-

sector participation in solution development.

Privacy and Identity

The laws, regulations, and standards that govern the protection of personal

information and the release, mandatory or otherwise, of data collected

or maintained by the U.S. Government are undergoing a period of

review. The triple challenges of IT advances, the globalized flow of data

for trade and other purposes, and the value, both legal and illegal, of

individually identifiable information have caused this relook. Advances

in IT have included an exponential increase in collection, storage, and

processing capabilities, including the development of machine learning

algorithms that greatly surpass human ability in pattern matching and

discovery. The globalized flow of data is fueled by electronic commerce,

off-shoring, and transnational workforces enabling 24/7 operations that

flow from time zone to time zone. Finally, the value of individually identifiable

information enables both good and bad things: it can not only assist

law enforcement and intelligence activities and enable better service,

but it also fuels identity theft, fraud, and blackmail.

This situation is exacerbated by the reality that different cultures approach

the definition and protection of privacy very differently. This difference

has complicated global commerce and international legal structures,

but solutions such as the European Union–U.S. Privacy Shield

have been developed to bridge such divides. Challenges remain. Existing

controls are structured for legacy structures and technologies. Emerging

technologies present new challenges. This new and evolving state of affairs

requires careful consideration to ensure that government activities

are consistent with social values, international trade agreements, and reality.

Several important initiatives are emerging to create a foundation for a

solid path forward. The creation of the Federal Privacy Council is critical

to these efforts and signals the importance with which the problems

associated with privacy and technology are considered. Similarly, the

National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has begun twin

efforts in developing guidance and standards for privacy and de-identification

processes. Emerging research from academia and industry in

topics such as privacy labeling and management, database privacy, and

differential privacy is critical to the development of tools and practices for privacy problems. There is an emerging community of practice of

privacy officers, mathematicians, computer scientists, and civil libertarians

that provides fora for the discussion and presentation of research.

Building on these initiatives provides a way forward to address privacy

and data release concerns. We offer these recommendations:

- Leverage the Privacy Council and NIST efforts to provide intellectual

support to the community of practice and create feedback mechanisms

to U.S. Government efforts.

- Prioritize funding the National Science Foundation and other government

research to support existing privacy enhancing functional

research, such as differential privacy.

- Fund research into the future of privacy, such as the issues associated

with big data analysis that derives private information from contextual

data, a lack of published information, or from cross-referencing

information from multiple sources. All these approaches have been

used to expose private information and present significant challenges

for both individuals who wish to keep aspects of their lives secret

and for governments that need to keep aspects of operations (such

as research and development and counterintelligence efforts) secret.

- Sponsor research into cascading effects from privacy violations that

subvert national goals in order to reveal currently unimagined policy

and scientific needs.

Foreseeing the Future of Identity

Concepts of identity are evolving in ways that are difficult to predict. In

the past, identity elements were defined through elements of personhood

(name, eye color), job (title, responsibilities), profession (lawyer,

doctor), relationship (family or network member), interests (hobbies,

habits), culture (values and belief systems, heritage, citizenship), and

political structures. Layering on those established identity elements are

new, cyber-enabled identities, which may or may not relate closely (or at

all) to physical reality.

Cyber identities may be expressed through a variety of means, including

avatars in artificial worlds, software bots that execute behaviors (such

as troll armies), affiliation with ad hoc communities (such as Anonymous),

or as social media characters. Besides being new ways to create

or express identity, these cyber-enabled identity elements can be difficult to relate to real people and thus cause challenges in realms as diverse as

national security and mental health. As cyber-innovation continues at

its breakneck pace, cyber-enabled identities and identity elements will

continue to evolve and mutate in ways that are difficult to predict, including

allowing people to “live” or express themselves through multiple

different identities or even many cloned identities.

There are important implications for this emerging fluidity in identity.

One is in governance: when one person can have multiple identities,

that person can opt in to multiple governance structures, ranging from

political to practice to commercial. Another is in security: identities can

be used to disguise or hide subversive activities, but may also be used

effectively to discover and understand alternative ways of thinking and

acting. There is benefit and worry; the balance between the two requires

significant understanding and structural philosophical approaches. We

offer the following recommendations:

- Appoint an interagency working group, with representatives from

the Justice, State, Defense, Transportation, and Homeland Security

departments, to formulate, lead, and coordinate legal approaches,

domestically and internationally, because cyber-enabled identities

can easily engage in behavior that crosses jurisdictional boundaries.

- Create an office in the Department of Homeland Security to engage

in dialogue with communities formed in the virtual world by cyber-enabled identities for communication and intelligence.

- Fund research into the implications (for example, psychological effects

or national security considerations) of single individuals engaging

in the virtual world through multiple cyber identities.

Technology for Governance

Explosive growth of unstructured data demands solutions to the challenge

of information management. As the use of mobile devices and sensors

grows and evolves, experts expect data volume to grow to over 4,300 percent

of 2009 levels by the year 2020. The Federal Government faces a need

to shift from collecting data to gaining new insights, identifying unexpected

patterns and trends, and using data analytics to find new solutions to

complex problems—an analysis best conducted using data visualization

techniques. Unfortunately, correctly interpreting trends and patterns hidden

in the data requires special skills in information and computing technologies

that are lacking in the current cyber workforce. Additionally, appropriate investment in the underlying technologies themselves lags well

behind need. Ultimately, information processing and visualization must be

improved for national leadership to make sense of the proliferation of data

in order to inform policy and decisionmaking.

Visual analytics is an especially compelling technology because of its potential to facilitate leadership’s ability to understand a situation quickly

and clearly and to make better decisions. However, a major challenge, in

addition to a very small talent pool, is the level of funding required for

high-end visualization resources and machine learning capability. Google

researchers note that machine learning can solve problems that no other

methods can but that the cost of the technology and maintenance of the

algorithms is significant and may be out of reach for individual organizations.13 A collective approach to develop capabilities that could then be

further customized for individual organizational use is warranted to make

these technologies affordable. We offer the following recommendations:

- Tap private sector and academic research to inform development of

objectives and policy regarding data visualization capabilities.

- Direct NIST to move more aggressively to instantiate a collaborative

model to catalyze development of data visualization capabilities for

the purpose of government sense-making and decisionmaking.

Decoding Encryption: Aligning Technology, Law, and Policy

The Nation faces the risk that our adversaries’ use of encryption technologies

to “go dark” will cause the loss of the ability to surveil their actions

in cyberspace.14 Terrorists are using the Dark Web and strong encryption

technologies to plan and execute their operations protected from government

surveillance.15 National security and law enforcement entities

desire a backdoor or master key built into the encryption algorithms or

legislation compelling companies to engineer their software allowing for

searches to surveil terrorists and investigate criminals.

The cryptographic, scientific, and technologic communities are united

in saying strong encryption is an all-or-nothing position and that

weaker encryption jeopardizes the global infrastructure of trust. Encryption

is founded in mathematical principles and is considered strong only

when it is subjected to rigorous public scrutiny. A weakness—whether

accidental or legislative—is a globally exploitable feature.

Strong encryption is important to national security. Critical infrastructure,

banking, commerce, and communications all rely on strong encryption

for security. Encryption protects and enables national defense, commercial activities, and freedom of speech. Public and private entities

use strong encryption to fulfill their obligations to protect personal information

under legislation (for example, the Health Insurance Portability

and Accountability Act and the Privacy Act of 1974).

Recent attacks in the United States, France, Belgium, and Turkey aided

by secret communications using strong encryption provide a case to

limit it. This, however, would not be effective. Encryption technologies

used by criminals and terrorists are not controlled solely by U.S. companies

or interests and cannot be effectively curtailed though U.S. legislation.

Additionally, methods to surveil and apprehend criminal and

terrorist actors who use encrypted technologies do exist. These methods

exploit how the actors build and use encryption technologies and the

infrastructures of the Dark Web. Additional research is needed, as many

methods and techniques were exposed and rendered ineffective by the

Edward Snowden leaks of 2013, but others can be developed. We offer

the following recommendations:

- Support use of strong encryption, acknowledging its utility for protecting

citizen data.

- Require use of strong encryption technologies in the Nation’s critical

infrastructure.

- Invest in advanced tools to identify and surveil criminal and terrorist

actors.

Developing a Coherent Artificial Intelligence Agenda

Between May and July 2016, the U.S. Office of Science and Technology

Policy (OSTP) completed four public workshops on artificial intelligence

(AI) to “identify challenges and opportunities related to this emerging

technology.”16 Focus areas included legal and governance, use for public

good, safety and control, and social and economic implications. Additionally,

OSTP created a new National Science and Technology Council

(NSTC) Subcommittee on Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence

to coordinate Federal Government activities in these areas. These two

initiatives demonstrate that AI is gaining attention, but they do not constitute

a strategy for assessing the associated benefits and risks in a comprehensive

manner.

With the imminent arrival of self-driving vehicles and precision

autonomous weapons systems, it is imperative that the United States

advance a coherent AI agenda addressing the technological, legal, and policy implications of this technological revolution. Failure to do so

threatens to leave the Nation incapable of benefiting from AI use for the

government or influencing responsible AI use in the private sector. We

offer the following recommendations:

- Charge the newly formed NSTC Subcommittee on Machine Learning

and Artificial Intelligence to maintain currency on AI capabilities

and trends, regularly convene diverse experts in the field, offer expanded

participation in the subcommittee, and produce actionable,

timely AI goals.

- Complete a formal review of White House expectations to influence

private AI use and implementation of AI in government.

- Conduct outreach to address public fears that AI may cause loss of

jobs or that autonomous machines may threaten public safety.

Modernizing Government Cyber Infrastructure

The White House and Congress must continue to reform IT acquisition

practices in order to meet modernization goals and objectives. Numerous

studies and congressional testimonies have highlighted the need for a synchronized

and cohesive strategy to plan, program, budget, and execute

modernization of IT. A May 2016 report by the Government Accountability

Office (GAO) found that Federal agencies are spending almost 75 percent

of the $88 billion IT budget to maintain legacy systems.17 The report

specifically identified that 5,233 of approximately 7,000 Federal IT systems

are spending all of their funds on operations and maintenance costs.

By comparison, development, modernization, and enhancement spending

for the same programs represents less than 25 percent of spending and

has declined $7.3 billion since 2010. The study also highlighted that numerous

systems were developed decades ago with parts and programming

languages that are now obsolete and pose significant risk. Some of the programs,

such as the DOD program that coordinates the operational functions

of the Nation’s nuclear forces, were developed over 50 years ago and

use 8-inch floppy disks that have long ceased being produced. In other

cases, agencies rely on outdated operating systems such as those from Microsoft

in the 1980s and 1990s that ceased vendor support long ago. As a

result, the GAO study found that agencies spend significantly more to hire

and maintain programmers who hold specific skill sets as well as expose

increased security risks. This comes at a time when more than $3 billion

worth of Federal IT investments will reach end-of-life in the next 3 years.

In response to these issues, the Office of Management and Budget

(OMB) developed the IT Modernization Fund (ITMF).18 The fund, as

part of the White House’s Cybersecurity National Action Plan, follows up

on the gains made from the Federal IT Acquisition Reform Act in 2014.19

The ITMF is in line with the recommendations from the May 2016 GAO

report and supports other modernization initiatives such as the General

Services Administration (GSA) 18F program.20 Success of the ITMF is at

risk unless several major weaknesses are addressed. We offer the following

recommendations:

- Establish a centralized board of experts to identify and prioritize the

most pressing legacy IT systems to be targeted for replacement with

a smaller number of common platforms.

- Provide an initial $3.1 billion in seed funding. Based on calculations

provided by OMB, the funding will address at least $12 billion in

modernization projects and generate the momentum needed to establish

a repayment process to ensure the ITMF is self-sustaining.

- Establish, under the oversight of the GSA, a centralized fund supporting

agency modernization plans, competitively distributed

based on plan quality.

- Leverage GSA experts in IT acquisition and development to support

agencies in implementing their modernization plans.

Improving the Cybersecurity Workforce

U.S. national security, the protection of critical infrastructure, and the effective

functioning of the Federal Government require reliable and secure

cyber-based government assets supported by a professional cybersecurity

workforce that protects these assets from all types of threats, including

cyber attacks. Recent breaches, including those resulting in significant

data losses at the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) and Internal

Revenue Service, revealed that the cybersecurity workforce is significantly

challenged in protecting the government’s cyber-based assets against

attacks. Efforts to generate the numbers of personnel with the requisite

competencies have been unsuccessful. The government lacks a coherent

and comprehensive approach to improve the cybersecurity workforce.

OPM has a responsibility to develop a holistic and proactive approach

to improve the cybersecurity workforce. This approach must include, but not be limited to, recruiting, hiring, developing, and retaining. We

offer the following recommendations:

- Establish a cybersecurity executive council composed of senior executives

from each department and agency to establish the executive

governance for cybersecurity workforce policies, initiatives, and

strategies.

- Develop and publish an updated job specialty standard specific to

cybersecurity positions to establish a single authoritative source for

cybersecurity positions.

- Establish common higher-level cybersecurity educational criteria to

create a baseline for cybersecurity educational requirements.

- Offer tuition assistance, reimbursement, and scholarships to enhance

retention of government cybersecurity workforce members

and attract new employees from the private sector.

- Index compensation for specific cybersecurity workforce positions

to comparable private sector positions in order to retain top performers.

- Require quarterly progress reports until these actions are fully implemented.

Sensing and Responding for Agile Government

Information technologies now feed a swelling appetite for real-time information.

Citizens demand and rely on data from their mobile devices

to make decisions (such as travel routes or which consumer product to

buy) that can immediately disrupt markets or drive new behaviors. Private

industry recognizes this as part of doing business in the 21st century.

Governments have not realized this and have failed to find ways to use

it to drive innovations.

Failure to adopt a strategy to serve citizen needs for information that

leverages the opportunities of technology while avoiding the inherent

challenges (privacy concerns, information overload, and so forth) places

the government at risk of losing relevance, confidence, and trust in

the eyes of its citizenry. Citizens will find information elsewhere and

construct their own stories about particular experiences with government

entities based on their perceptions of the value realized from the interaction. Worse yet, citizens may find governance of no value or fill

any vacuum with information from untrustworthy or biased sources to

construct their perception of events and motivations.

These alternate sources have demonstrated their ability to seize opportunities

to sense public mood and provide the storylines that will

advance their cause by taking advantage of gaps in public information

and any signs of insecurity or fear. They feel no obligation to be truthful

or unbiased. The same dynamic has reduced the time allowed, from the

emergence of a public policy issue through the development and implementation

of policy to address it, such that the failure to immediately

address a problem is viewed as unresponsiveness. Civil movements rely

on cost-effective, instantly deployed social media platforms to engage

advocates and escalate favorable public opinion. These same platforms

can be used to cultivate public friction and hateful or counterproductive

civic positions that present obstacles to positive government initiatives.

In this context, government has also failed to seize the opportunity

to employ the same information technologies to develop a better sense

of how citizens perceive public good and how they find value in government

service delivery models. There is a need for the administration

to establish a sensing framework to develop insights regarding if it is

serving or failing to serve those to whom it is accountable. This applies

whether dealing with cyberspace or traditional governmental obligations

in establishing trust and engagement by the technology-enabled citizen.

A positive outcome of such an initiative would be the repackaging of

government data and information to proactively explain internal decision

factors, competing agendas, and crowdsourced data gaps to external

consumers. This could illuminate the complexity of governance activities

and decrease the need to seek substitute data sources. Effectively it offers

content for civic education and distributes responsibility for governance

to a community of interested people. This new vision embeds contemporary

consumer sense-making in the practices of the good governance.

We offer the following recommendations:

- Charge the Federal CIO with rapidly crafting a strategy to synchronize

and elevate e-government initiatives into effective citizen engagement

capabilities addressing needs for information dissemination,

service provision, and gauging citizen valuation of government

policy, services, and transparency.

- Link agency IT funding to successful implementation of the Federal

CIO strategy (referenced above) to engage citizenry using required

metrics on citizen-perceived utility of systems, trustworthiness of governance messaging, transparency of governance processes and

decisionmaking, and government responsiveness to citizen needs.

- Develop a Web-based performance dashboard to present customizable

views of internal policy administration data metrics, provide a

more accessible window into government institutional activity and

value creation, and promote accurate perceptions of government

activity.

Conclusion

In a short time, cyber has emerged as both a warfighting domain, fully

as significant as the land, sea, air, and space domains, and an omnipresent

public-private operating universe. The potential opportunities

found within the domain of information and cyberspace are seemingly

limitless. The risks of this reliance are clear, as demonstrated by recent

highly publicized network breaches. It is important that these risks be

deliberately accounted for and addressed in the process of making decisions

about the use of cyberspace.

Cyber competence must be part of the skill set for all senior leaders in

the national security enterprise. Most senior leaders received their professional

educations at the beginning of the cyber age, and their understanding

of, and sensitivity to, the opportunities and vulnerabilities described

above may be limited. Nevertheless, mastery of the cyber domain

has now assumed critical importance because of our dependence on cyberspace.

Agency heads must be held accountable for their organization’s

employment of information technologies—abrogation of responsibility

to CIOs and other “cyber experts” is unacceptable.

Addressing the critical challenges of cyberspace must be approached

with an understanding of limitations and risks inherent in the use of the

technologies that underpin the domain’s potential. The authors here have

highlighted promising opportunities and areas of concern. Specific recommendations

are offered to contribute to a Presidency ready to embrace

both the risks and the opportunities facing the Nation in cyberspace.

------

The authors would like to thank the following contributors to their

chapter: William S. Boddie, James Churbuck, Cathryn Downes, Carl

J. Horn, Michael D. Love, Jenny Hall Mandula, Kenneth D. Rogers,

John L. O’Brien, Julie J.C.H. Ryan, Paul Shapiro, George Trawick, and

Veronica J. Wendt.

Notes

1 Joint Publication 3-13, Information Operations (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, 2014), available at <www.dtic.mil/doctrine/new_pubs/jp3_13.pdf>.

2 White House Fact Sheet, “Cybersecurity National Action Plan,” February 9, 2016, available at <www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2016/02/09/fact-sheet-cybersecurity-national-action-plan>.

3 Executive Order 13691, “Promoting Private Sector Cybersecurity Information Sharing,” February 13, 2015, available at <www.federalregister.gov/articles/2015/02/20/2015-03714/promoting-private-sector-cybersecurity-information-sharing>.

4 Presidential Policy Directive (PPD) 20, “U.S. Cyber Operations Policy” (2012), is a classified document that provides a framework for the roles and responsibilities of the executive branch’s agencies in cyberspace as well as a framework for U.S. cybersecurity. PPD-21, “Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience” (2013), provides a top-down risk management architecture and directed the creation of the national critical infrastructure centers for enhanced information-sharing and collaboration. Supporting PPD-21 is Executive Order 13636, “Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity,” which focuses on the cyberspace security aspect of PPD-21. PPD-41, “United States Cyber Incident Coordination” (2016), articulates how the Federal Government coordinates its incident response activities to significant cyber incidents.

5 Charles Perrow, Normal Accidents: Living with High-Risk Technologies (New York: Basic Books, 1984).

6 Manuel Castells, “Informationalism, Networks, and the Network Society: A Theoretical Blueprint,” in The Network Society: A Cross-Cultural Perspective, ed. Manuel Castells

(New York: Edward Elgar Publishers, 2004).

7 Laura DeNardis, Internet Points of Control as Global Governance, Internet Governance Paper No. 2 (Ontario, Canada: Centre for International Governance Innovation, 2013).

8 John Kamensky, “Why Isn’t Performance Information Being Used?” Government Executive, October 14, 2014, available at <www.govexec.com/excellence/promising-practices/2014/10/why-isnt performance-information-being-used/96347/>.

9 U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), Managing for Results: Agencies’ Trends in the Use of Performance Information to Make Decisions, GAO 14-747 (Washington, DC: GAO, 2014).

10 PPD-21.

11 Nathan E. Busch and Austin D. Givens, “Public-Private Partnerships in Homeland Security: Opportunities and Challenges,” Homeland Security Affairs 8, no. 18 (October 2012), available at <www.hsaj.org/articles/233>.

12 “Cyber Security Strategy of the United Kingdom: Safety, Security and Resilience in Cyber Space,” 2009.

13 Zachary Chase Lipton, “The High Costs of Maintaining Machine Learning Systems,” KDNuggets News, 2015, available at <www.kdnuggets.com/2015/01/high-cost-machinelearning-technical-debt.html>.

14 Senate Hearing on Worldwide Threats, 2016.

15 The Dark Web is commonly defined as a sub-portion of the Internet that consists of Web sites, portals, and social media similar to the open Internet, but that is accessible only through specially designed Web browsers and using technologies that easily anonymizes the user and encrypts all of his traffic, data, and activities.

16 Ed Felton, “Preparing for the Future of Artificial Intelligence,” WhiteHouse.gov, May 3, 2016, available at <www.whitehouse.gov/blog/2016/05/03/preparing-future-artificial-

intelligence>.

17 “Federal Agencies Need to Address Aging Legacy Systems,” GAO.gov, May 25, 2016, available at <www.gao.gov/products/GAO-16-696T>.

18 “Federal Agencies: Reliance on Outdated and Unsupported Information Technology: A Ticking Time Bomb,” hearings before the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, House of Representatives, 114th Cong., testimony of the Honorable Tony Scott, available at <https://oversight.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/2016-05-25-Scott-Testimony-OMB.pdf>.

19 White House Fact Sheet, “Cybersecurity National Action Plan.”

20 GAO, Building the 21st Century Digital Government, available at <https://18f.gsa.gov/>.