DOWNLOAD PDF

The continued sluggish recovery from the Great Recession of 2008–2009, the

reduction in U.S. employment, and the significant and growing Federal deficit

places increasing pressure on defense spending and threatens future U.S. national

security. The new administration must recognize the importance of and advocate

for policies to improve economic growth, responsibly address America’s fiscal

challenges, and rationalize defense spending. At over $550 billion, defense

spending is the largest discretionary part of the budget, representing 15 percent

of total Federal spending. The Pentagon should continue to address military

compensation reform, tackle the expansion of headquarters staffs, choose research

and development over procurement, and strenuously argue for entitlement

reform and increased fiscal responsibility. This approach can make significant

improvements in defense spending that will enhance U.S. national security.

The American defense budget for 2017 to 2020 will be one of the first

and most important issues that the new administration must address.

Realistic economic and budgetary policies must be developed and implemented

to replace the shortsighted and piecemeal approach that has dominated

Federal and defense budgetary decisionmaking for the past several

years. By taking specific steps regarding the defense budget, the new administration

can maximize the military contribution to national security.

To understand the challenges facing defense budgeting, this chapter

first examines the problems in the underlying economy, including the

implications of the national debt and deficit. It then discusses Federal

spending, including briefly reviewing the patchwork of solutions over

the past decade that has delayed and exacerbated budgetary problems.

With this context established, it identifies the necessary approach toward

Federal budgeting in general and defense budgets in particular.

Finally, the chapter discusses areas in which defense spending should be

reformed and improved.

The Economic Context

Although 8 years have passed since the Great Recession of 2008–2009,

the U.S. economy continues to suffer from the decisions made during

that time. While the average annual nonrecession growth since 1970 has

averaged over 3.5 percent, since the end of the Great Recession, the U.S.

economy has grown at just over 2 percent. The 1.5 percent difference in

economic growth may seem inconsequential, but, when compounded

over the next 10 years, the economy will be $3.4 trillion less than it

would have been with previous, more robust growth levels. That $3.4

trillion in lost output is as large as total annual Federal spending.

Why has growth declined? Well-intentioned programs approved

during and after the Great Recession that were designed to help American

citizens have reduced incentives to work. Unlike previous recoveries

when unemployment fell because more people were employed,

since the Great Recession most of the reduction in unemployment has

been because workers left the workforce. Labor force participation has

fallen from over 66 percent before the recession to 62.5 percent today.1

That is over 8.8 million fewer Americans seeking employment, and

their departure from the labor force reduces the productive potential

of the U.S. economy.

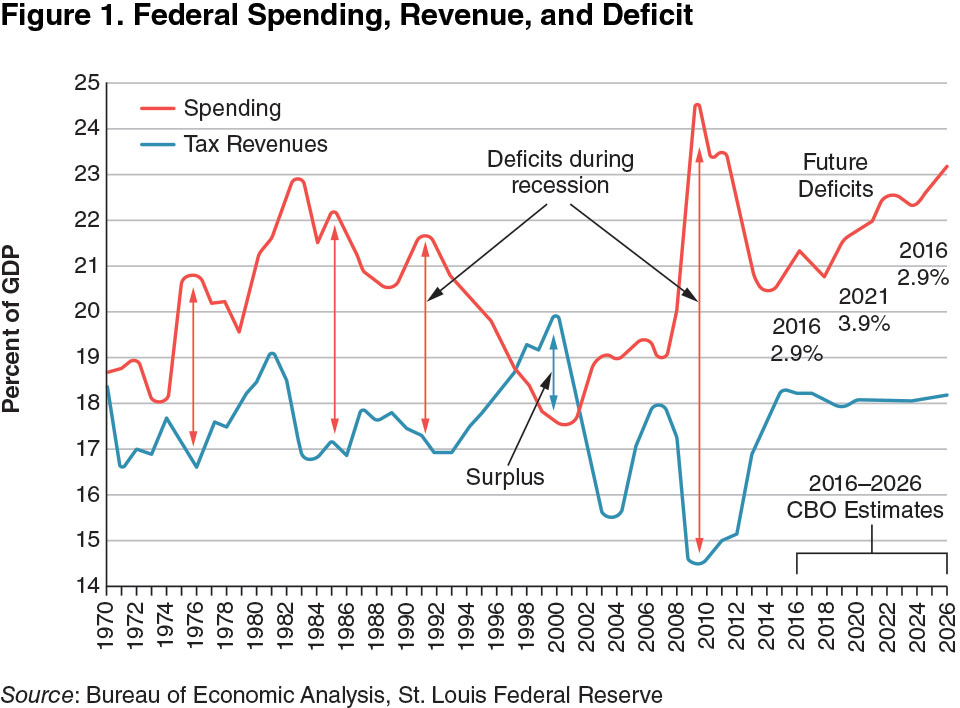

In addition to a decline in economic growth, another lingering effect

of the Great Recession is expanded government spending without

a commensurate increase in tax revenues, which has led to persistently

large annual deficits, reflected in figure 1 as the gap between the top

line (expenditures) and the bottom line (revenues).2 Consequently, the

national debt (which reflects the sum of annual deficits) has grown to

over 100 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) for the first time

since World War II.3

A fundamental question that confronts the Nation is raised on the

right side of figure 1, which projects future deficits. The 2016–2026

lines reflect the Congressional Budget Office projection for the Federal

budget, optimistically assuming no future recession. The shortfall between

18 percent of GDP in projected revenue and 21 to 23 percent

of GDP in projected spending cannot be sustained indefinitely. Consequently,

there is substantial pressure to reduce all forms of spending,

including defense spending.

What does this have to do with defense? Everything. U.S. defense

budgets in the future depend, in part, on economic policies that both

increase incentives for growth of the U.S. economy and address the challenges

of the long-term fiscal debt. Former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs

of Staff Admiral Mike Mullen aptly observed, “The single biggest threat

to national security is our debt.”4 The next administration’s civilian and military leaders must recognize the importance of and must advocate for

policies to improve economic growth and responsibly address American

fiscal challenges.

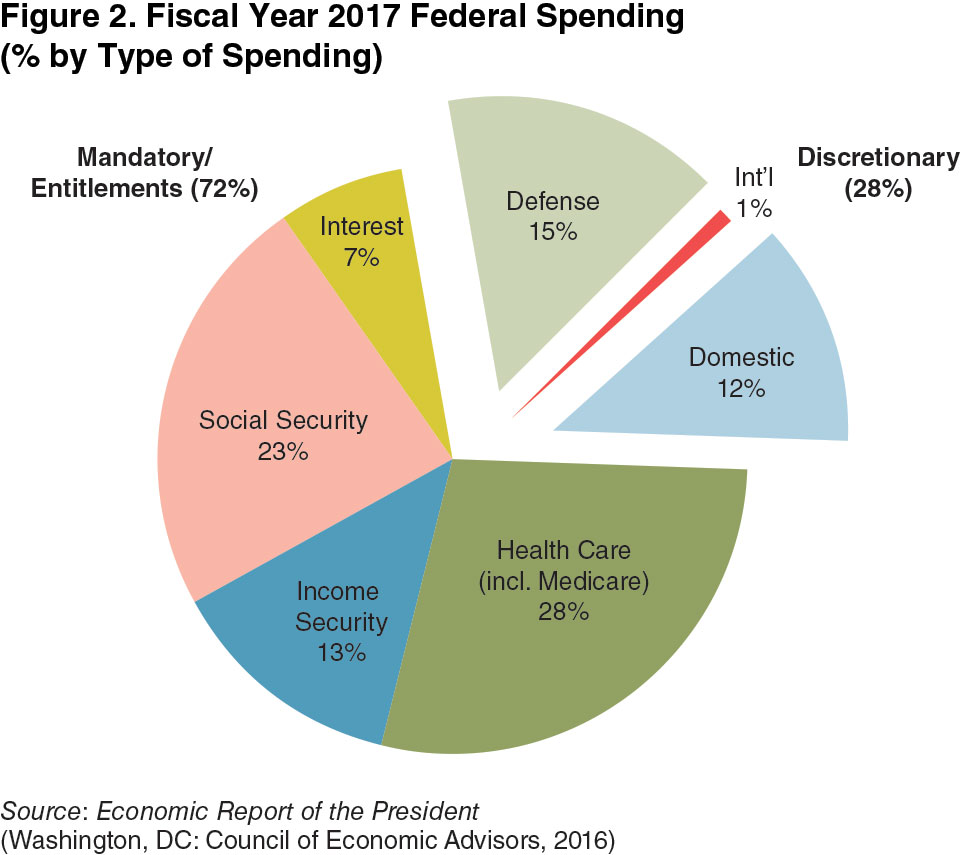

Overall Federal Spending

Defense is disproportionately dependent on Federal budget policy because

defense spending represents the largest discretionary portion

of the budget. As indicated in figure 2, most of the Federal budget is

“mandatory spending”—paying interest on the debt and providing entitlements

established by law. Entitlement spending includes programs

that comprise a social safety net, such as income security, Medicaid, and

healthcare subsidies. Other entitlements are contributions from taxpayers’

and their employers’ paychecks, such as Social Security, Medicare,

and military retirement. Although political leaders are reluctant to reduce

entitlements, the fact that they represent two-thirds of the Federal

budget requires any meaningful policy solutions to Federal budget challenges

to include entitlement reform.

The defense budget will face increasing pressure in the next 4 years

from other competing requirements for Federal spending, such as higher

interest payments as interest rates rise from their historic low levels, increased

Social Security and Medicare payments for retiring baby boomers,

and bolstered funding for homeland security and domestic priorities. The best way to more effectively provide for the Nation’s defense

may not be a new weapons system or military unit, but rather support of

comprehensive, long-term entitlement and budget reform.

Budgeting by Crisis

The Federal Government has a comprehensive process for planning,

programming, budgeting, authorizing, appropriating, and executing

the Federal budget. The problem is that for the past several years, the

normal political and budgetary process has failed because of extreme

polarization in Congress and inability to compromise except in crises.

Understanding this history is important so that the next administration

can learn from it and avoid perpetuating budgeting by crisis in 2017 and

beyond.

Most recently in August 2011, the Nation was only days away from

exceeding the debt limit and, absent congressional action, could have

potentially failed to meet obligations to pay entitlement recipients, Federal

workers, holders of U.S. debt, and Federal contractors. Congress

reached a last-minute compromise by raising the debt ceiling and passing

the 2011 Budget Control Act. That act bought time by appointing

a bipartisan Joint Committee on Deficit Reduction (the so-called Super Committee) that was supposed to solve the budget impasse and provide

a clear, rational way forward. In the absence of a solution by the Super

Committee, a process known as sequestration would automatically

implement dramatic and severe reductions of discretionary outlays to

achieve a specified amount of savings.

Even with the threat of automatic sequestration budget cuts, the Super

Committee could not achieve compromise. In September 2013 sequestration

was imposed, which slashed $109 billion from discretionary

spending, with half coming from defense spending and the other half

coming from non-defense spending (entitlement spending was exempt

from cuts). Other than military salaries, every defense and non-defense

account was reduced across the board, leading to the involuntary furlough

of government workers, curtailment of contracts, and other unplanned

reductions. The next crisis began on October 1, 2013, when

Congress failed to approve the fiscal year 2014 budget and the Federal

Government “shut down” for 16 days. To avoid another government

shutdown, Senator Patty Murray (D-WA) and Representative Paul Ryan

(R-WI) negotiated the Murray-Ryan budget plan, which forestalled any

crises through the 2014 election year but did so by granting $63 billion

in sequester relief through the end of fiscal year 2015.5

With the risk of sequestration reemerging in 2016, the official Department

of Defense Quadrennial Defense Review concluded:

The return of sequestration-level cuts in FY2016 [the

current law] would significantly reduce the Department’s

ability to fully implement our strategy. . . . Risks associated

with conducting military operations would rise substantially.

Our military would be unbalanced and eventually too

small and insufficiently modern to meet the needs of our

strategy, leading to greater risk of longer wars with higher

casualties. . . . Ultimately, continued sequestration-level

cuts would likely embolden our adversaries and undermine

the confidence of our allies.6

This is extraordinary because it is a statement that following the law,

which is the obligation of all Federal departments, would lead to devastating

consequences. When Congress approved the 2016 defense authorization

in October 2015, it evaded sequestration limits by counting

some regular spending as “overseas contingency operations” (which was

designed to cover only war costs). President Barack Obama vetoed the

bill, not because it violated the lawful Budget Control Act, but because

domestic spending did not have a similar exception to circumvent sequestration.7 After a new budget deal was struck, both domestic and

defense spending were increased for fiscal year 2016, postponing and

increasing the budgetary problem for the next President and Congress.

This budget-by-crisis approach in use since 2011 reflects a dysfunctional

Washington environment that has preoccupied defense budgetary

decisionmaking and distracted officials from using the budget process

to make difficult but necessary choices for the good of the Nation. One

of the most important attributes that the next President should bring to

Federal spending is a clear articulation of national priorities and leadership

to work with Congress to develop and execute a coherent, longterm

budget strategy to accomplish those priorities. Certainly compromise

will be necessary on some issues, but in the absence of leadership

to solve fundamental problems, the resulting budgetary chicanery will

continue to undermine American economic strength and hamper national

security.

Budget Solutions

Budget problems are completely within the Federal Government’s power

to solve. The solutions will entail some kind of realistic long-term entitlement

reform, a reduction in discretionary spending, an increase in total

tax revenue raised, or any combination of the three to cause the lines in

figure 1 to move closer together rather than spread farther apart. In 2010

the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, chaired

by former Senator Alan Simpson (R-WY) and former White House Chief

of Staff Erskine Bowles, developed a plan that would reduce the Federal

deficit by nearly $4 trillion in 10 years, reducing the deficit to 2.3

percent of GDP.8 More recently former Senator Pete Domenici (R-NM)

and former Office of Management and Budget Director Alice Rivlin with

the Bi-Partisan Policy Center have proposed a similar plan. Importantly,

both of these plans, and any that would likely be successful, encourage

incentives for increased employment and economic growth, which are

essential to any long-term solution. With regard to revenues, most bipartisan

plans maintain or reduce tax rates while eliminating “tax expenditures”

(also known as loopholes) so that the ultimate result is more tax

revenues through greater productive output and less manipulation of the

tax code to favor specific actions, industries, or sectors of the economy.

Defense Spending as Part of the Solution

Reform of the defense budget, representing half of the discretionary budget,

must play a significant part in solving the Federal budget challenges.

A first step for the next administration to address the defense budget is

to understand both the level and composition of U.S. defense spending

and how these have changed over the past 15 years.

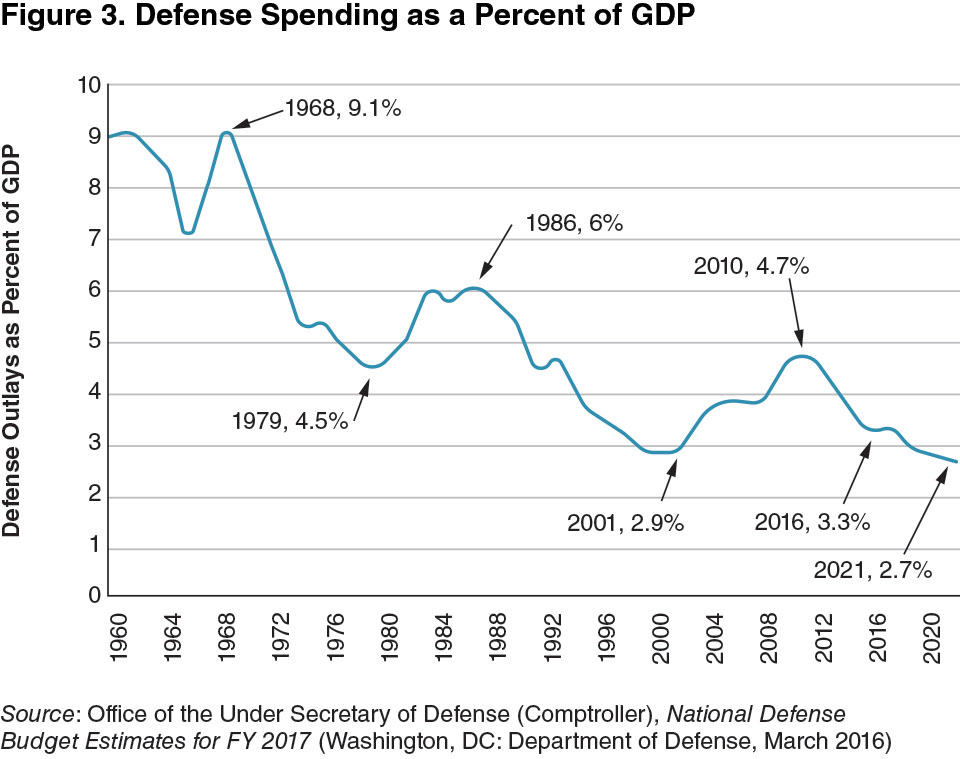

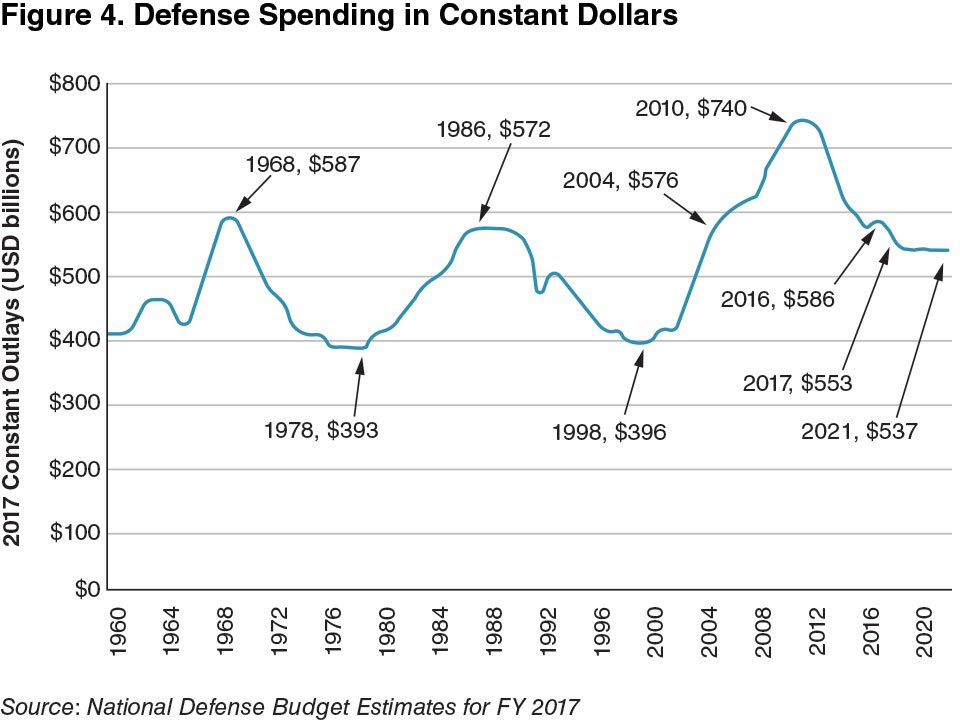

Overall Spending

To some extent, the size of the defense budget depends on one’s perspective

because all of the following facts are true. The current defense

budget:

- projects using the smallest proportion of U.S. national income since

World War II (see figure 3)

- is 21 percent less than peak spending in 2010 (see figure 4)

- is about the same inflation-adjusted amount as was spent in Vietnam

in the 1960s or during the Ronald Reagan–era military buildup

in the 1980s

- is larger than that of the next eight nations combined, as President

Obama has highlighted.9

The size of the defense budget should be a function of national interests

and strategic objectives. The sine qua non of a superpower is that it

must have a military capable of engaging with other nations throughout

the world and the capability to engage in multiple conflicts nearly simultaneously.

Such engagement with a technology-based all-volunteer force

is inherently expensive, which is why, even after the withdrawal of most

forces from Iraq and Afghanistan, the U.S. defense budget today remains

similar to spending at the height of the Cold War, after adjusting for

inflation (see figure 4).

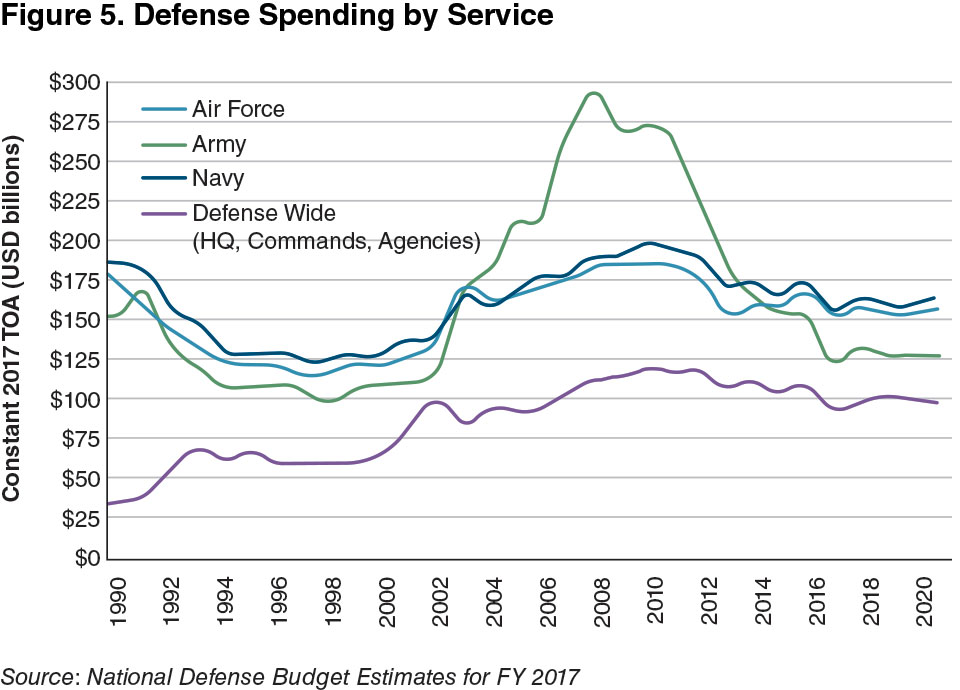

Each of the military Services generally responds differently to the

budget, depending on the portion it receives (see figure 5). Although

the Army receives additional funding during wartime, its budget has

now returned to the regular 23 to 25 percent share that was its normal

Cold War–era spending percentage. The Navy and Air Force each comprise

approximately 30 percent of the budget. Defense-wide agencies

and commands consume a consistently increasing portion of the defense

budget, slowly reducing the shares going to each Service. Defense-wide

spending has grown to about 18 percent of the defense budget today,

which underestimates its proportion of resources because it does not

include any military personnel costs (which are part of the individual

Services’ budgets with military members assigned to the defense agencies

and commands).

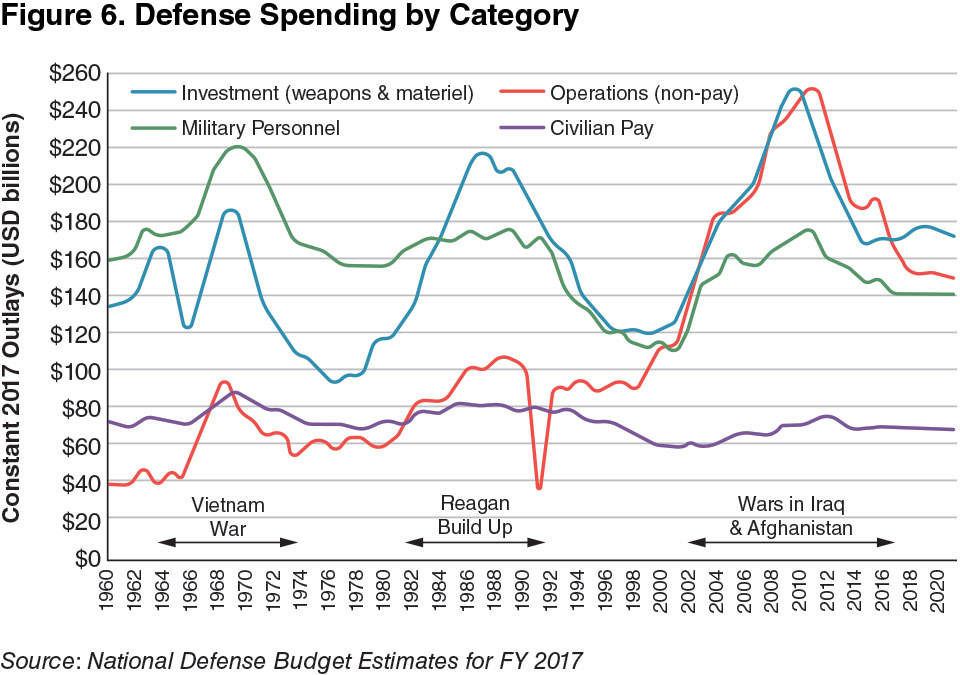

Although the total defense budget is similar, the composition of defense

spending has changed significantly in the past 15 years, which has

profound implications for the next administration. The four major components

that drive defense spending are military personnel, civilian pay,

investment (weapons and materiel), and operations. In previous wars

spending in all categories generally increased. For example, during the

Vietnam War (illustrated on the left side of figure 6), each of the lines

rises in roughly the same proportion, with military personnel spending

representing the highest category of expenditure. During Vietnam, total

military personnel expanded from 2.48 million in 1960 to 3.58 million

in 1968, including approximately 2.2 million who were drafted over the

course of the war.10

When the draft ended and the all-volunteer force began in 1973, defense

leaders made a conscious decision to scale down to a smaller, more

professional military, which fundamentally changed the way that America

would fight wars from then on. The military shifted to a more efficient

force with significantly fewer personnel using much better equipment.

The personnel shift has been dramatic and has had a corresponding impact

on defense spending. On September 11, 2001, the military had 1.45

million in uniform, less than half of the total during the Vietnam era,

and the Army had 480,000 Soldiers, which was less than one-third of

the 1.51 million soldiers during Vietnam.11 Before 9/11, the Nation had

not had to sustain the all-volunteer force during a period of prolonged

conflict. There were very real concerns about whether the Department of Defense (DOD) could recruit and retain sufficient personnel during

a long war. Additionally, then–Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld

decided against increasing the military’s size, so the wars in Afghanistan

and Iraq were fought with the existing force, albeit with some mobilization

of the Reserves.12

Effects of the Last 15 Years

With the need to sustain the all-volunteer force as an underlying assumption

of the U.S. defense strategy, global operations since 9/11 in

Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere have had three significant, persistent

budgetary effects. The first effect is that, like previous wars, all categories

of spending increased—military personnel for mobilization and additional

costs, investment to purchase new or replace destroyed equipment,

and operations to cover deployment and warfighting costs. These

wars account for some of the increase in all categories of spending on the

right side of figure 6.

The second effect is that operations spending (the red line in figure

6, adjusted for inflation) increased disproportionately from $100 billion

in 1999 to over $250 billion in 2011. With a limited number of troops

available, the DOD strategy concentrated on using the operations budget

rather than uniformed military to accomplish essential tasks whenever

possible. This is not necessarily the wrong approach—just one that is

different from the way that previous wars have been fought. In previous

wars U.S. military logistics, transportation, maintenance, and construction units conducted base support and other sustainment operations in

combat theaters. Today the number of military logistics units has been

significantly reduced, and that work is contracted out through increased

operations spending. Similarly some security operations and training of

foreign military forces were outsourced to private military security companies

in lieu of committing as many U.S. troops for those tasks. Some

of those operations funds were expended to train and equip the Iraqi,

Afghan, and other foreign armies to rightly carry the burden of defense

in their own nations.

Much of this operational spending was for contracted labor. In both

Iraq and Afghanistan, the number of contractors normally exceeded the

number of U.S. troops deployed. For example, the number of DOD-employed

contractors peaked with 163,591 contractors in Iraq in December

2007 and 112,092 contractors in Afghanistan in March 2010.13 For

every 10 uniformed military deployed in the Balkans, Afghanistan, and

Iraq, there have been 10 to 12 contractors. By contrast, in Vietnam,

World War I, and World War II, for those same 10 uniformed military,

there were fewer than 2 contractors.14 Although costly, using contractors

was probably less expensive than recruiting, training, deploying,

and sustaining military in those positions, even if that would have been

possible in the absence of a draft. And those contractors certainly shared

the risks of combat, with over 3,200 U.S. contractors killed in Iraq and

Afghanistan—representing 32 percent of Americans killed in action.15

Increases in the operations budget, however, were not limited to

training foreign forces and increasing contractors on the battlefield. Using

contractors for wartime deployments extended to routine operations

as well. Rather than use limited military or government civilian workers,

DOD has increasingly relied on contractors with a commensurate increase

in the non-pay operations budget. In fiscal year 2011, for example,

DOD spent $144.5 billion to purchase 709,879 full-time equivalent

(FTE) years’ worth of contracted services (at an average cost of $203,565

per FTE).16 While expensive, contracting did provide an immediately

responsive workforce to accomplish critical missions, especially during

wartime. However, DOD may have grown overly reliant on contractors

and high operations funding as a wartime exigency and must now readjust

back to a new normal for budgeting and operations. The next

administration must recognize this sea change in the way that DOD accomplishes

its institutional work and determine the best mix of military,

government civilian, and contractor resources to more effectively and

less expensively accomplish operations in the future.

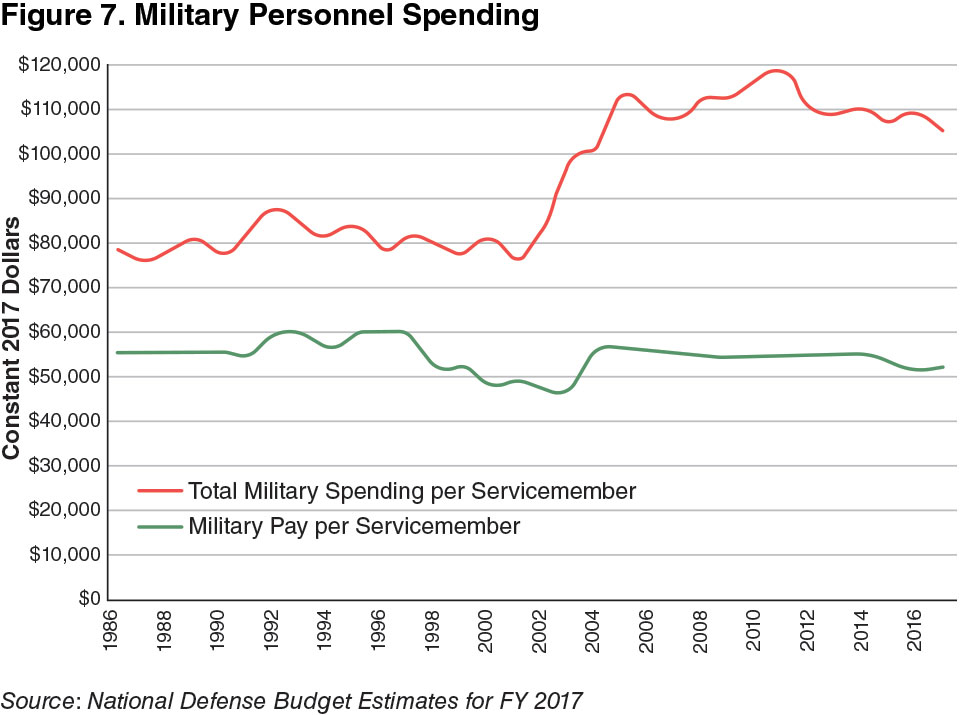

The third effect of the wars of the last 15 years has been the increase

of military personnel spending per person. Measured in constant (inflation-

adjusted) dollars, the average basic military pay for Soldiers, Marines,

Sailors, and Airmen has remained relatively constant for the last

three decades, as reflected by the bottom line on figure 7. However, after

9/11, with the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, total military personnel

spending per Servicemember significantly increased, primarily through

increases in non-pay military personnel costs to ensure the continued

viability of the all-volunteer force, a trend that has been consistent with

the political need to “take care of the troops.” Previously, non-pay military

personnel costs primarily consisted of accrual for military retirement.

Since 9/11, costs of expanding services, improving the quality of

housing, providing incentive pays, contributing to Medicare for retirees,

paying unemployment compensation, and other obligations have significantly

increased total military personnel spending in addition to base

pay. This is not to say that increases in total military personnel spending

are not well deserved, but those increases have driven up the cost of

each person in uniform, as reflected by the top line in figure 7. Although

the military has fewer people today than at any time since World War

II, total military personnel costs are 25 percent higher than they were in

2000, after accounting for inflation. The high cost of military personnel

presents a challenge to DOD that is akin to the problem of entitlements

at the Federal level. The benefits are well deserved and were granted for

all of the right reasons, but the rising cost of total compensation is almost

pricing military personnel “out of the market.”

These three effects of the wars of the past 15 years—increased spending

overall, increased contractors and operations spending, and increased

per-person personnel costs—have led to a defense budget that is

both large and in need of critical restructuring to provide clear direction

and a path forward for the future national security of the United States.

Recommended Improvements

Given this understanding of the fiscal realities that confront the Nation,

the next administration will need to take four specific steps with regard

to the defense budget for 2016–2020. First, the defense budget

for 2016 to 2020 must include ways to “bend the curve” on military

personnel spending but must do so without breaking faith with those

serving, who are truly deserving. In the absence of such reforms, the

only solution that military leaders would have left is to further cut the

number of Servicemembers in uniform. Fortunately in 2015, DOD took

a step toward military compensation reform with the first major change

in military retirement since World War II.17 This reform included adding

a government contribution to a 401(k)-like defined contribution plan,

and reducing military retirement benefits by 20 percent. Ultimately the

change will save about $2 billion per year.18 Further reforms, such as

the one for military retirement, should be coordinated with across-theboard

entitlement reform from other parts of the Federal budget so that

financial sacrifices necessary for the Nation’s long-term fiscal stability

and economic growth are borne by American citizens generally and not

just placed on the shoulders of those who serve.

Making these adjustments in benefits will require courage and leadership,

which has already been expressed by senior military leaders. The

Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps, Michael Barrett, testified to Congress,

“In my 33 years, we’ve never had a better quality of life. . . . We’ve

never had it so good. If we don’t get a hold of slowing the growth [of

personnel spending], we will become an entitlement-based, a healthcare

provider–based Corps and not a war-fighting organization.”19 Barrett was

arguing the point made in figure 7 that the costs are simply too high and

that if they are not contained, funds will be redirected from equipment

and training that are essential to combat readiness. The next administration

would likely find that military leaders would welcome reasonable

reforms of military entitlements to curb cost growth, especially in conjunction

with other Federal entitlement reforms.

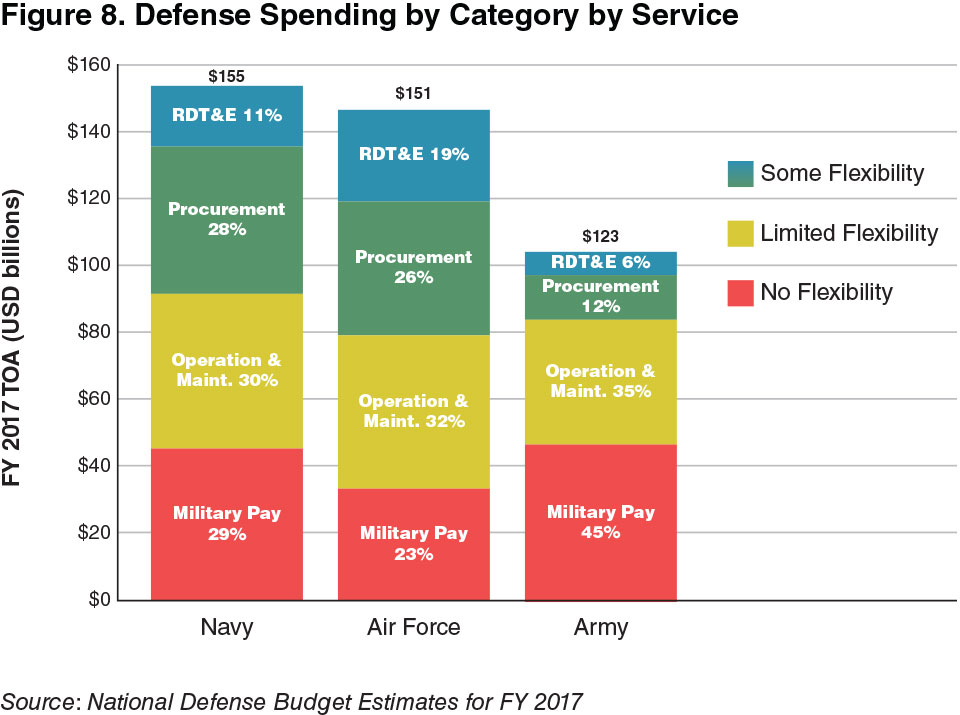

Rising personnel costs affect all Services but are especially prominent

in the Army. Although the Army is downsizing, it still has the most uniformed

personnel; in fiscal year 2017, military personnel costs represent 45 percent of its budget (see figure 8). This share is of a smaller budget

and is about 50 percent more than the Navy’s share of personnel costs

(which includes the Marine Corps) and double that of the Air Force.

Consequently, when there is a further call for flexibility within budgets,

especially after reductions in spending for overseas contingency operations,

the Army has severely limited budgetary options.

Second, the next administration should increase efficiency and return

more resources to operational units by using the defense budget process

as a forcing mechanism to discipline and reduce the size of headquarters.

Understandably, in the midst of fighting multiple wars, the military

forms additional structures, organizations, and headquarters, frequently

in an ad hoc way. Many of these are effective, such as the Rapid Equipping

Force, which was created during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq

to harness “current and emerging technologies to provide immediate

challenges of U.S. Army forces deployed globally.”20 However, these innovations

were often in addition to, rather than instead of, the existing

institutional structure. Now is the time to reduce the previous structures

and to right-size defense institutions proportional to the force that they

are supporting.

|

Table 1. Military and Civilian Positions in DOD Headquarters

|

|

|

2001

|

2005*

|

2013

|

Increase (%)

|

|

Office of the Secretary of Defense Staff

|

2,205

|

|

2,646

|

20

|

|

Joint Staff

|

|

1,262

|

2,599**

|

105.9

|

|

Army

|

2,272

|

|

3,639

|

60.2

|

|

Air Force

|

2,423

|

|

2,584

|

6.6

|

|

Navy

|

|

2,061

|

2,402

|

16.5

|

|

Marine Corps

|

|

2,352

|

2,584

|

9.9

|

|

* The Joint Staff, Navy, and Marine Corps did not have comparable numbers for 2001.

**Joint Staff increase was largely due to disestablishment of U.S. Joint Forces Command in 2011.

Source: Government Accountability Office, DOD Needs to Reassess Personnel Requirements for the Office of Secretary of Defense, Joint Staff, and Military Service Secretariats, GAO-15-10 (Washington, DC: GAO, January 2015), 10–17.

|

One of the most critical areas to examine has been the growth of headquarters

staff over the past 15 years. Each headquarters in the Pentagon

has increased significantly since 9/11 (see table 1).21 These increases are

only for civilian and military positions and do not include contractor support, which can also be significant. For example, in addition to 2,646

military and civilians, the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) staff

employs 3,287 contractor FTEs in support of its operations.22 Similarly,

the combatant commands have grown substantially in personnel and

costs over the past decade. Excluding U.S. Central Command, whose

growth is understandable from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the

other five geographical combatant commands (U.S. Northern Command,

U.S. Southern Command, U.S. European Command, U.S. Pacific

Command, and U.S. Africa Command) have grown from 6,800 in 2001

to 10,100 in 2012, with a similar increase in Service components supporting

those commands.23 Although some of that increase was clearly

justified (about 1,100 positions with the creation of U.S. Northern Command,

which had new responsibilities), when U.S. Africa Command was

created in 2009 from U.S. European Command, the latter did not experience

a concomitant decrease in size.

When the Pentagon, Service, and combatant command headquarters

are totaled, there are 55,965 military and civilian personnel assigned to

those staffs, excluding contract support and field operating agencies supporting

those staffs.24 Those people, who represent the equivalent of 11

Army brigades or Marine Corps regiments, are certainly working hard

doing important work. However, to constrain the growth of the budget,

increase efficiencies, and prioritize the work being performed, the next

administration should determine what part of the work that has been accumulated

over the past 15 years from Congress, the White House, OSD,

combatant commands, and Service staffs should be reduced or eliminated.

Such a review should also examine the number of DOD senior leaders.

Today there are 943 flag officers, including 37 four-star generals and

admirals. That is 8 percent more than the total in 2001, while the size of the military is 5 percent smaller.25 Leadership in reducing headquarters

and flag officers must come from the top because no Service will “unilaterally

disarm” by reducing its flag officers so that it is disadvantaged

in inter-Service or interagency discussions. For example, in the past 10

years, the Judge Advocate General of each Service has increased in rank

from major general to lieutenant general. For over 200 years, having a

two-star as the top Service lawyer was sufficient during periods where

there were many more Servicemembers and units needing legal support.

Reducing the rank and prestige of this and any other position will be

difficult, unless such adjustment is coordinated with Congress and imposed

by DOD. Secretary of Defense Ash Carter’s recent speech calling

for reform and reduction of four-star billets is a step in the right direction

that the next administration should build upon.26

Similarly, the number of civilian leaders in the Pentagon has expanded

even more than their military counterparts. At the height of the Reagan

military buildup in 1985, with 2.2 million military on Active duty and significant

ongoing procurement, there were only 2 under secretaries of defense

and 11 assistant secretaries of defense. Today there are 5 under secretaries

of defense, 16 assistant secretaries of defense, and a corresponding

increase of military assistants, principal deputies, deputy assistant secretaries,

and other staff members.27 If these new OSD positions replaced

work previously done by each of the military Services with a concomitant

reduction of Service staffs, the increase could be justified. In many cases, however, a bigger, higher-level staff necessitates increases in subordinate

staffs to keep pace with the additional requirements, meetings, coordination,

and oversight. DOD needs a comprehensive right-sizing of the staff,

and the budget process is the appropriate forcing mechanism to begin

that reduction. Budget savings from headquarters reductions can provide

savings that can preserve resources for important DOD priorities.

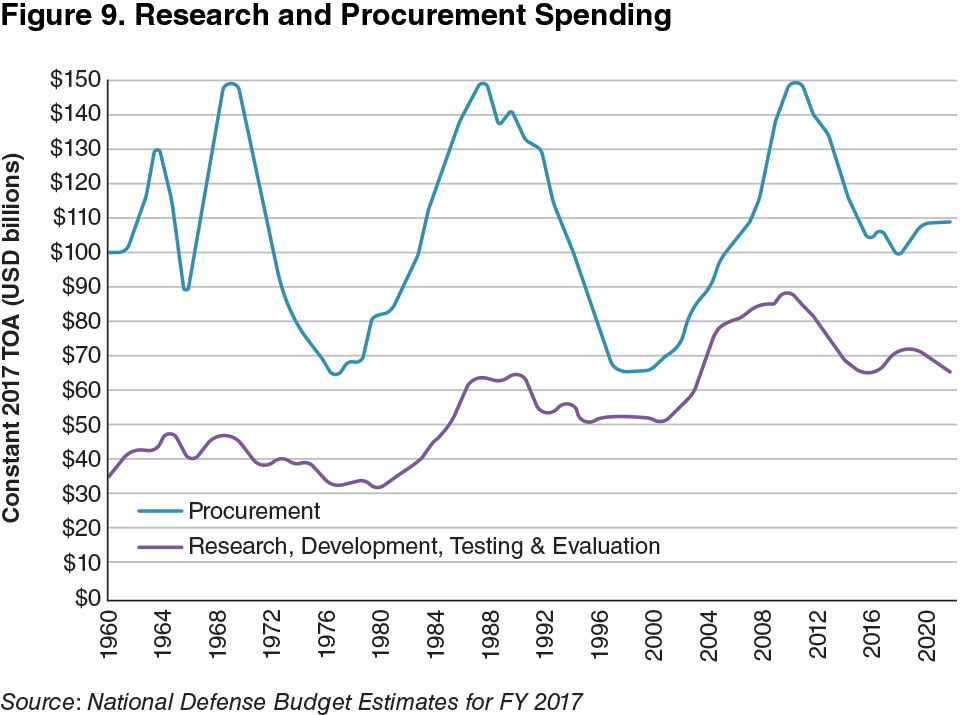

Third, DOD should accept risk in procurement programs as long as

there is a sufficient way to sustain research and development to spur

technological progress. As shown in figure 9, the rapid drop in procurement

from 2010 to 2015 is both understandable and a step in the right

direction. Arguably, however, spending on research and development

(bottom line of figure 9) should continue to be increased—even at the

expense of current procurement.

Although there are certainly technological threats on the horizon, especially

in the area of cyber warfare, it is not clear which weapon systems

will be most effective in the future. It could be a waste of funds to field or

replace massive systems, particularly when the United States is unlikely

to face a technologically superior enemy in the near future. Moreover,

technology is advancing so rapidly that systems procured today may

become obsolete tomorrow. This was the case in both the 1970s and

1990s when DOD shifted investment dollars away from procurement to

research and development, which paid dividends in the following decades

when procurement was required and funds were available. Today,

the largest procurement expenditures, such as those reflected in table 2,

focus on ships, aircraft, and submarines, areas in which the United States

already has significant technological superiority.28 The challenge for the

next administration is to develop the budgetary and political support for

research and development in the cases where large-scale procurement is

neither appropriate nor necessary.

|

Table 2. Top Weapons System Acquisitions (FY 2017, USD millions)

|

|

Program

|

Research and Development

|

Procurement

|

Total

|

|

F-35 Joint Strike Fighter

|

1,801

|

8,703

|

10,505

|

|

Virginia-class Submarine

|

209

|

5,114

|

5,322

|

|

DDG-51 Arleigh Burke–class Destroyer

|

149

|

3,349

|

3,498

|

|

KC-46A Tanker Aircraft

|

262

|

2,885

|

3,319

|

|

Gerald R. Ford–class Nuclear Carrier

|

121

|

2,665

|

2,786

|

|

B-21 Long Range Strike (Bomber)

|

1,911

|

287

|

2,198

|

|

P-8A Poseidon Aircraft

|

57

|

2,108

|

2,165

|

|

Ohio-class Submarine Replacement

|

1,091

|

773

|

1,864

|

|

Evolved Expendable Launch Space Vehicle

|

297

|

1,506

|

1,803

|

|

America-class Amphibious Assault Ship

|

10

|

1,639

|

1,648

|

|

Littoral Combat Ship

|

137

|

1,462

|

1,599

|

Especially since the end of the Cold War, it has been difficult to garner

the political support for significant weapons systems in the absence of

a massive program, even if the Service’s need is to research, support, or

improve existing systems rather than to develop a new one. The Army’s

experience has been painful, as its last three major weapons projects

have been canceled. The Army leveraged the circumstances to “win despite

losing,” using reprogrammed funds to support existing programs

in lieu of the failed programs. When the Crusader cannon was canceled,

funds were reprogrammed into Excalibur precision-guided munitions

and other artillery upgrades. When the Comanche helicopter was canceled,

funds were used for modernization of the existing helicopter fleet.

When the Army’s largest procurement, the Future Combat System (FCS),

was canceled, some of the procurement funds committed to it were reallocated to further develop some FCS technologies, modernize existing

Army brigades, and begin development of the new Ground Combat Vehicle.

Had the Army merely requested relatively smaller scale programs

for artillery, helicopter, or ground combat vehicles, it is unlikely that

such requests would have garnered sufficient institutional or political

support. Defense acquisition could be significantly improved and budget

allocations reduced if funds were prioritized to be spent on equipment

that Services truly need as opposed to programs that are larger than necessary

just to obtain political support.

Finally, the ultimate step to addressing the challenge of defense

spending ties back to the ability of the Nation to adequately fund defense.

Future defense spending constraints will be largely determined

by the extent of increased overall economic growth, reduced entitlement

spending, and lower deficits. The defense top-line as currently projected

(including the 2016 “exception” to the sequestration constraint) is

barely sufficient to sustain defense that is appropriate for a superpower

with global responsibilities. Assuming that U.S. strategic ends remain

unchanged, the only viable budgetary approach to support continued

defense spending of $553 billion (in fiscal year 2017 dollars) is to aggressively

support economic and fiscal policies that increase economic

growth and reduce entitlement spending in the long term. Although this

may be perceived to be “out of the lane” of military leaders, it is the only

way to ensure sufficient funding to provide for adequate national security

in the future. Defense officials should emphasize that military retirement

reform was the first major change to Federal entitlement spending

in two decades and should build on that fiscal leadership as a reason to

call for similar reforms in non-defense entitlements as well.

Conclusion

The next administration has an opportunity to set an aggressive agenda

for the Pentagon as it continues to engage globally, sustain the all-volunteer

force, prepare for the future, and confront increasing budgetary

pressure. To be successful, defense leaders must understand the reasons

for the current economic and fiscal crises and the accumulated effects

of 15 years of war on the Services, on the level and composition of the

defense budget, and on the military establishment as a whole. The current

strategy of muddling through from one budget crisis to the next is

inefficient, counterproductive, and unsustainable. In response to these

conditions, the next administration should continue to address military

compensation reform, tackle the expansion of headquarters staffs,

choose research and development over procurement, and strenuously argue

for entitlement reform and increased fiscal responsibility. The power

to make these changes lies entirely with the leadership in Washington.

The next administration should seize that power and use it to make the

improvements in defense spending to enhance U.S. national security.

----

Dr. Steven Bloom, Colonel S. Jamie Gayton, USA, and Dr. R.D. Hooker, Jr.,

provided extremely helpful comments on a previous version of this chapter.

Notes

1 Bureau of Labor Statistics, “The Employment Situation—November 2015,” USDL-

15-2292, December 4, 2015, available at <www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/empsit_12042015.pdf>.

2 Calculations based on data from Economic Report of the President (EROP) (Washington,

DC: Council of Economic Advisors, 2016), tables B-17 for fiscal years 1970–2017;

The Budget and Economic Outlook, 2016 to 2026 (Washington, DC: Congressional Budget

Office, January 2016), table 1.

3 See EROP, 2016, table B-18. The 2017 national debt is projected to be $20.1 trillion,

which is 104.4 percent of gross domestic product. Of this total, $14.8 trillion (73.3 percent

of gross domestic product) is debt held by the public, and the balance is the portion

of debt that is held by government agencies (such as trust funds).

4 Geoff Colvin, “Adm. Mike Mullen: Debt is Still Biggest Threat to U.S. Security,”

Fortune, May 10, 2012.

5 U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on the Budget, “Murray and Ryan Introduce

Bipartisan Budget-Conference Agreement,” press release, December 10, 2013.

6 Quadrennial Defense Review 2014 (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, March

4, 2014), 53.

7 Steven Mufson, “Obama Uses Veto for Only Fifth Time, Rejecting Defense Authorization

Bill,” Washington Post, October 22, 2015.

8 National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, The Moment of Truth

(Washington, DC: The White House, December 2010).

9 Barack Obama, “State of the Union Address,” Washington, DC, January 12, 2016,

available at <www.whitehouse.gov/sotu>.

10 Personnel statistics are from Office of the Undersecretary of Defense, National

Defense Budget Estimates for FY 2016 (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, March

2015), table 7-5. Draft estimates are from Bernard Rostker, I Want You: The Evolution of the

All-Volunteer Force (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2006), 44.

11 Moreover, by comparison, the U.S. population in 2001 was 42 percent larger than

it was in 1968. Data on historical size of the military are from Department of Defense,

Selected Manpower Statistics, FY 2005 (Washington, DC: Defense Manpower Data Center,

2005).

12 In 2006, after Secretary Donald Rumsfeld resigned, President George W. Bush

approved an increase in Army and Marine Corps end strength. See Donald Rumsfeld,

Known and Unknown: A Memoir (New York: Sentinel, 2011), 715.

13 Moshe Schwartz and Joyprada Swain, Department of Defense Contractors in Afghanistan

and Iraq: Background and Analysis, R40764 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research

Service, May 13, 2011).

14 Defense Science Board, Task Force on Contractor Logistics in Support of Contingency

Operations (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, June 2014), 10.

15 As of March 15, 2015, the U.S. contractor deaths in Iraq and Afghanistan were

1,620 and 1,592, respectively. In comparison, U.S. Servicemember deaths were 4,483 in

Iraq and 2,353 in Afghanistan. See Sara Thannhauser and Christoff Luehrs, “The Human

and Financial Costs of Operations in Afghanistan and Iraq,” in Lessons Encountered: Learning

from the Long War, ed. Richard D. Hooker, Jr., and Joseph J. Collins (Washington, DC:

NDU Press, September 2015).

16 Government Accountability Office (GAO), Continued Management Attention Needed

to Enhance Use and Review of DOD’s Inventory of Contracted Services, GAO-13-491 (Washington,

DC: GAO, May 2013), 14–15. It is important to note that $203,565 is the fully

burdened cost of the full-time equivalent (including payments made to the contractor,

which includes recruiting, training, taxes, retirement costs, and other expenses; it is not

just the salary paid to the individual).

17 The Department of Defense (DOD) proposed the change in retirement based on the

Military Compensation and Retirement Modernization Commission and was included

in the 2016 National Defense Authorization Act. The military retirement system has not

substantively changed since World War II. There was one change in 1986—a proposal for

“Redux” retirement was passed that would have saved DOD significant retirement costs—

but that was essentially repealed in 1999, before it could save DOD personnel costs.

18 The new retirement plan has many additional details and is outlined in Report of

the Military Compensation and Retirement Modernization Commission (Washington, DC:

Department of Defense, January 2015). The $2 billion in forecasted savings is in Tom

Vandenbrook, “Defense Secretary Ash Carter’s Historic Personnel Changes Irk Generals,”

USA Today, December 27, 2015.

19 Michael Barrett, quoted in “Sgt. Maj. of the Marine Corps Barrett: Less Pay Raises

Discipline,” Marine Corps Times, April 9, 2014.

20 “Rapid Equipping Force,” available at <www.ref.army.mil/>

21 Table 1 is based on GAO, DOD Needs to Reassess Personnel Requirements for the Office

of Secretary of Defense, Joint Staff, and Military Service Secretariats, GAO-15-10 (Washington,

DC: GAO, January 2015), 10–17.

22 Ibid., 52.

23 GAO, DOD Needs to Periodically Review and Improve Visibility of Combatant Command’s

Resources, GAO-13-293 (Washington, DC: GAO, May 2013).

24 Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Readiness and Force Management,

Defense Manpower Requirements Report, FY 2015 (Washington, DC: Department of Defense,

June 2014), 18.

25 The number of current flag officers is from Defense Manpower Requirements Report,

Fiscal Year 2015 (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 2014), 73; Selected Manpower

Statistics, Fiscal Year 2001 (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 2001). The reduction

in the size of the military is from National Defense Budget Estimates for FY 2016.

26 See Ash Carter, “Remarks on ‘Goldwater-Nichols at 30: An Agenda for Updating,’”

April 5, 2016, available at <www.defense.gov/News/Speeches/Speech-View/Article/713736/>.

27 The best listing of DOD officials is Department of Defense Key Officials, September

1947–May 2015 (Washington, DC: Historical Office of the Office of the Secretary of

Defense, 2015).

28 Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), Program Acquisition Cost by

Weapon System (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, February 2016).