V. Women's Equal Access to the Means for Recovery

Women and girls’ vulnerabilities are often exacerbated in crisis contexts. While participating in activities such as food distribution, firewood collection, and travel to and from latrines and water points, for example, they may be separated from protective family structures and face increased risks of trafficking . . . sexual exploitation and abuse, or other harm. Rape in conflict situations can increase the incidence of HIV/AIDS, affecting not only women but also their families. Conflict also increases the incidence of disability, and women with disabilities can face particular risks including social stigma and isolation, difficulty accessing humanitarian assistance, unmet health care needs, and higher rates of [sexual and gender-based violence] and other forms of violence during and after conflict.

—United States National Action Plan on Women, Peace, and Security

15. Women in Relief and Recovery:

Putting Good Policies into Action

By Valerie Amos

Humanitarian workers are the first responders when disaster strikes. They deliver the most urgent, lifesaving aid in crises caused by natural disasters and those that arise from conflict, as we have seen in Syria, Afghanistan, and Somalia. In all these countries, humanitarian agencies and their local partners on the ground work to get food, water, shelter, and healthcare to people who have fled their homes because of violence. Our job is to try to reach everyone in need, regardless of who or where they are.

How we accomplish this mission makes the difference between saving a greater or smaller number of lives, between helping people back on their feet or leaving them at the mercy of another crisis down the line. But our response can be either effective or wasteful. People are not all the same; they do not have the same needs even in emergency situations. The cultural and other norms that overlay the way men and women are seen and treated in ordinary situations apply, sometimes in an amplified way, during crises.

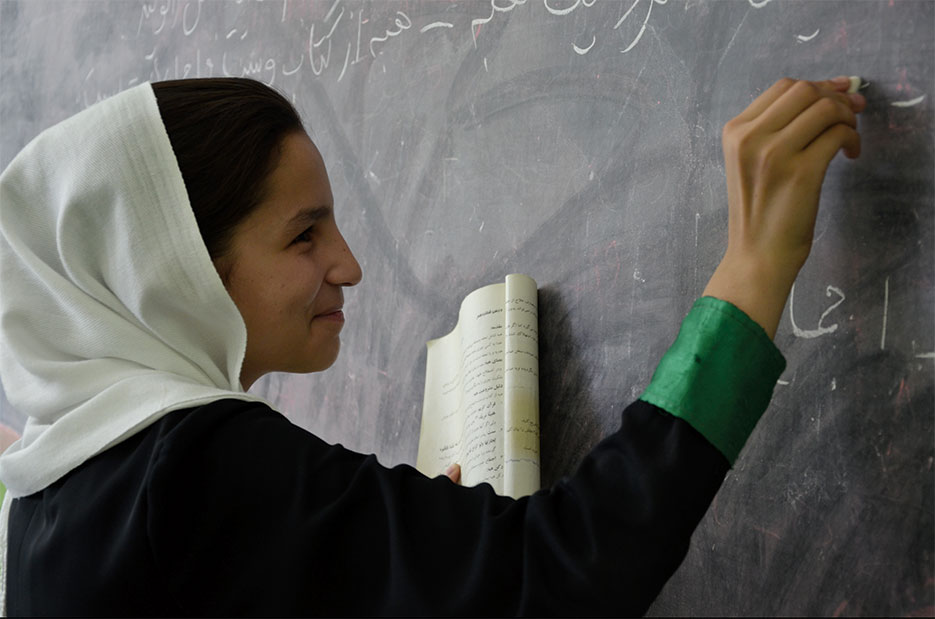

Student writes on chalkboard during English class at girls’ school in Kabul, Afghanistan, June 2011 (DOD/Catherine Threat)

Disasters are discriminatory. They generally affect women and girls in significantly different ways from men and boys. One of the best examples comes from the Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004. Two-thirds of those who died in Indonesia’s Aceh Province were girls and women. In some parts of India and Sri Lanka, four women were killed for every one man. Why? Because many women in coastal villages were at home while their husbands and sons were out fishing, many women put their children’s safety before their own, many women had never learned to swim, and even those who had were impeded by their clothing.

In emergencies triggered by conflict, the use of sexual violence as a weapon of war and the general breakdown of social norms mean women and girls can suffer disproportionately. It is often women and children who flee their villages, leaving men and sometimes the elderly behind to guard property. Between 70 and 80 percent of refugees around the world are women and children.1 Women face particular risks associated with their sex. The statistics are incomplete, but we know that women refugees are more affected by gender-based violence than any other group of women in the world.

Recent reports from Syrian refugees in Lebanon and Jordan illustrate the terrible plight of women during wartime.2 As of February 2013, one in five families in these camps is headed by a woman.3 Their stories of attack and rape in public and at home, primarily by armed men, are heartbreaking. Those who do survive fear retribution by their assailants or being killed by family members who believe they have been dishonored. Many mothers marry off their daughters far too young in the hope of keeping them safe from abuse. For those who manage to flee, there is a shortage of medical and counseling services to help them recover.

Studies show that girls in refugee camps are less likely than boys to attend school and learn to read, which can affect their economic prospects and those of their community for a generation. Girls and women who are sexually assaulted may be cast out from their communities, rendering them unable to look after their children, which in turn dramatically increases the likelihood of health and nutrition problems for the whole family far into the future.

Humanitarian agencies are proud of the impartiality they show in the way they deal with people. They do not discriminate against aid recipients depending on religious or political affiliations, locations, or sex. However, a failure to take the disproportionate effects of crises on women and girls into account means that, in reality, discrimination is a fact of life.

Take something that seems straightforward, such as the construction of latrines in a refugee camp. Studies show that unless toilet cubicles are segregated by sex, located close to where people are living, and have adequate lighting and lockable doors, they will not be used by women and girls. Up to one-third of the latrines constructed after the Haiti earthquake were not used because women and girls feared that by using them, they would be exposed to abuse. Or consider the provision of medical care in Afghanistan. National figures show that across the country, there is one health worker per 7,000 Afghans. But a breakdown of this figure by sex shows that there is one male health worker per 4,000 men, and one female health worker per 23,000 women, in a country where many women cannot be treated by a male doctor or nurse for cultural reasons. The consequences of failing to take gender differences into account are tragic; more women will die from lack of care.

Why It Is Essential to Gather Sex and Age Data

Staff Sergeant Erika Bonilla, USMC, stated, “I became a drill instructor because I wanted to make a difference and become a positive female role model to these young women” (U.S. Marine Corps/Caitlin Brink)

Humanitarian aid is based on programs designed using information about people in need. This is where we must distinguish between men, women, boys, and girls. This means collecting and analyzing data divided by sex and age, which is known as SADD (sex and age disaggregated data). Collecting SADD may seem like a trivial change to working practices, but it is a proven way to save lives and prevent suffering, and its importance is widely recognized and recommended.4

But there are still huge disparities in collection and use of SADD in designing humanitarian programs. Sectors such as health and education register and track the people they are helping, and they have a strong record of distinguishing between girls, boys, men, and women. In Afghanistan, for example, figures showed that girls’ education was falling far behind boys’ because of disruption during the Taliban era and a lack of schools in rural areas. This evidence was used by the Afghan Ministry of Rural Development and Reconstruction and by development agencies to target the building of schools and increase the enrollment of girls. Today, Afghan girls make up between one-third and one-half of all students enrolled in primary and secondary education—a higher proportion than ever before.

However, sectors such as food and sanitation are less successful at targeting women and girls through efficient data collection. Research in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2009 showed that less than a quarter of internally displaced women and 8 percent of returnee women were registered for food rations, despite the United Nations (UN) World Food Programme’s goal of ensuring that 80 percent of targeted households received rations through women. In agriculture, the situation was even worse, with more than 95 percent of all agricultural kits distributed to men in a country where women produce 75 percent of the food.5

The reasons for these situations are complex. Agencies sometimes subcontract construction projects and food distribution, so humanitarian workers may not have regular contact with beneficiaries. Donor support for food distributions also tends to be unconditional, meaning that there is less outside pressure on agencies to change. The agenda for big international donors to respond to an emergency is often set during the first few days and weeks, so it is particularly important to ensure that women’s voices are heard and perspectives understood right from the start. However, this is also the time when chaos is at its height, and it is difficult to collect and transmit reliable information.

Another problem is that humanitarian data tend to be simplified several times after collection and before programs are designed, so that even if detailed information on the sex and age of beneficiaries is gathered in the initial stage, it may be lost by the time it is transmitted to a regional office or agency headquarters.

The message here is simple. It is more time-consuming and difficult to gather and analyze larger amounts of more detailed data. But it is vital if we are to meet the needs of the people we are trying to help as effectively as possible.

Recent Progress

We are now tackling the issue of women’s representation on several different fronts and are making some progress. One of the most important tools is the Gender Marker, which scores humanitarian projects on whether they meet the distinct needs of different groups of people.6 It works not only by assessing project design, but also by promoting greater reflection on gender issues and on what makes a good project. A pilot study showed that simply including it in project assessments resulted in a significant increase in the provision of information about gender issues, which in turn means that programs are more likely to meet women’s needs.

The introduction of the Gender Marker tool was supported by the assignment of gender experts to the Sahel region of West Africa, in Sudan, South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Niger, Kenya, Somalia, Liberia, and Afghanistan to train, advise, and encourage staff in gender analysis. This has generally been recognized as a success, and there are many more requests for deployment waiting to be filled.

Other recent signs of progress include greater interest from donors in funding projects based on disaggregated data. The British government is currently funding a research study on recovery from conflict in seven countries, which requires information on gender. The United States, Australia, and the Nordic countries are also pushing for greater use of disaggregated data in project design and evaluation.

The moves toward better use of evidence throughout the humanitarian system, from strategic planning to monitoring, will also provide new ways for women’s perspectives to be included and prioritized. For example, new tools that assess the needs of people in emergencies will include ways of systematizing the collection of sex and age disaggregated data, ensuring that the distinct needs of women and men are considered from the start.

Combating Gender-Based Violence

A greater focus on combating gender-based violence is another key area in which we are seeing progress, although not enough. Gender-based violence has not historically been seen as a priority lifesaving activity even though physical attacks are a leading cause of death for women between the ages of 15 and 44. Gender-based violence can have a devastating and lasting impact on health, from acute and chronic physical injuries and disabilities to mental health problems, both for the women affected and for children born as a result of this abuse. Gender-based violence not only affects women and girls and their families, but it can also hold back their communities and societies. It is also increasingly recognized as an economic and development issue. Violence against women has enormous direct and indirect costs for survivors, employers, and the public sector. It is a fact of life for women in many countries in times of peace, and it becomes even more prevalent and damaging in times of crisis.

Increasing awareness of the prevalence, injustice, and costs of gender-based violence is driving new campaigns to reduce and eliminate it. Humanitarian agencies are playing their part by involving women and girls in designing programs that reduce risks, give them greater protection and control, and provide treatment in emergency situations. Temporary shelters with lockable doors are replacing tents at camps for displaced people in Somalia. Trauma counseling for women is part of the basic healthcare provision in refugee camps. We also need to design and implement programs that promote gender equality and target men and boys as the main perpetrators of gender-based violence.

Better collection and analysis of basic data are also helping to raise awareness of gender-based violence, prevent it, and deal with its effects. Cultural taboos mean that such violence is often underreported, and humanitarian agencies are finding ways to build confidence in data collection and storage systems so that women and girls can have confidence that their identities will be protected.

Hmong women and child in Mae Salong, Thailand, where women’s labor accounts for two-thirds of subsistence agriculture, yet they often have no rights over land, June 2011 (United Nations/Kibae Park)

What Donor Countries Must Do

Recognizing women’s distinct needs in crises and emergencies can no longer be portrayed as a luxury or an add-on; it is the only way in which we can fulfill the obligations placed on us by the UN General Assembly and Security Council and the expectations of the global public.

Donors, including the U.S. Government, have an important role to play in pressing humanitarian agencies to meet the distinct needs of women and girls in crises. They have an influential role both in their interactions with humanitarian agencies and on the Security Council where they decide on the subjects under discussion and on the mandates given to peacekeeping and political missions. Donor governments can improve women’s and girls’ access to humanitarian aid in the following ways:

- Refuse to fund projects that do not address the different needs of all segments of society and increase funding to those that do.

- Combat gender-based violence by supporting projects that improve the security and safety of women and girls in camps and affected communities.

- Demand that humanitarian actors collect, analyze, and use SADD to inform humanitarian programming.

- Work with the boards of UN agencies to ensure that they prioritize SADD and are fully gender-sensitive.

- In the Security Council, ensure that reporting clearly indicates how men and women are affected by crises and emergencies and that statements and resolutions take the needs and experiences of all sectors of society into account.

- Stress the fundamental importance of international law and use all means available to prevent and sanction the use of sexual violence as a weapon of war.

I encourage all in the donor and humanitarian system to work harder to build on the progress we have made in recent years. We know what we need to do; now we just have to do it.

Notes

- See Women’s Refugee Commission, “Children and Youth,” 2013, available at <http://womensrefugeecommission.org/programs/youth/763-girlsstories>; International Rescue Committee, “Frequently Asked Questions about Refugees and Resettlement,” available at <www.rescue.org/refugees>; and “Human Rights and Refugees,” Christian Science Monitor, available at <www.csmonitor.com/1998/0325/032598.opin.opin.1.html/%28page%29/3>. In 2011, however, about 72 percent of refugees were women and children. See United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Displacement: The New 21st Century Challenge (New York: UNHCR, 2012), available at <www.unhcr.org/51bacb0f9.html>. In the Syria crisis, an estimated 73 percent of the 1.64 million refugees are women and children. See UNHCR, “Syria Regional Refugee Response,” available at <http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/regional.php>.

- See Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), “Top Stories Search by Country: Lebanon,” available at <www.unocha.org/top-stories/stories-by-country/results/taxonomy%3A184>.

- See UNHCR, Vulnerability Assessment of Syria Refugees in Lebanon: 2013 Report (New York: UNHCR, 2013). See also UNHCR, 2013 Syrian Refugees at a Glance: Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey (New York: UNHCR, February 2013), available at <data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/download.php?id=1531>.

- See Dyan Mazurana et al., Why Age and Sex Matter: Improving Humanitarian Response in Emergencies (Medford, MA: Feinstein International Center, 2011), available at <www.unocha.org/top-stories/all-stories/humanitarian-issues-why-age-and-sex-matter>.

- Ibid., 48. “According to Delphine Brun, [Gender Consolidated Appeal Process] Advisor who worked in the Demographic Republic of Congo (DRC), it is very likely that in DRC the numbers set by policy makers were not reflected in the reality on the ground. While [UN World Food Programme] policy recommended that 80 percent of the targeted households receive their food rations through adult female members, in North Kivu only 23 percent of the IDP [internally displaced persons] women and 8 percent of returnee women were registered for ration cards. Similarly, in South Kivu, while 80 percent of IDP women were reached, figures were as low as 20 percent among returnee women. For agriculture the situation was even worse, as 96 percent of the agricultural kits were given to men, in a country where women produce 75 percent of the food.”

- See OCHA, “Gender Marker,” available at <www.unocha.org/cap/Resources/gender-marker>. See also Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), “IASC Gender Marker—Frequently Asked Questions,” July 29, 2011, available at <https://docs.unocha.org/sites/dms/CAP/Gender%20Marker%20FAQ%2029%20July%202011.pdf>.

16. Promoting Women’s Participation in Disaster Management and Building Resilient Communities:

A View from U.S. Pacific Command

By Miemie Winn Byrd

U.S. Pacific Command (USPACOM) is charged with helping our partner nations prepare for and respond to disasters through such efforts as education, planning, preparation, assessing preparedness, coordinating operating procedures, conducting training exercises, and on-the-ground assistance. Like the rest of the world, we rely on the United Nations Hyogo Framework for Action,1 the fundamental planning document that describes and details the work required from all different sectors to reduce disaster losses. The Hyogo Framework was developed and agreed on with a wide range of partner governments, agencies, and disaster experts. Among other things, the Hyogo Framework identified a gender perspective as one of the four cross-cutting issues that must be kept in mind when planning for and responding to disaster in order to reduce risk, keep losses low, and build resilience.

Cryptologic Technician (Technical) 2nd Class Lisa Quincy working at Habitat for Humanity project in Lawndale, California, supported by volunteer efforts of several USS Abraham Lincoln (CVN 72) Sailors (U.S. Navy/Zachary A. Hunt)

All human relations and social organizations vary somewhat by gender. Cultural attitudes toward gender shape each individual’s behavior—and, as a result, when, where, and how she or he might be vulnerable. More particularly, gender inequalities—limits on women’s abilities to access information, control money and resources, and make decisions about their own lives and behavior—can put women and girls at additional risk in disasters.

When women and girls are at higher risk, entire communities are put in danger because women tend to be responsible for caring for the young, the elderly, the sick, and those living with disabilities. If the family loses the male breadwinner or head of household, she becomes additionally responsible for the well-being of the family. Any gender inequality is therefore magnified in a disaster and must be considered in planning. Discriminatory laws and sociocultural attitudes and habits thus can hold back a community’s disaster recovery.

To help protect women, experts now advocate ensuring that women are involved in planning and preparing for disasters. Simply having women participate is not enough, however. Women must have the power to influence and make decisions and to allocate resources. Here are two critical recommendations as USPACOM moves forward with integrating gender analysis in its disaster preparedness assistance:

- Ensure nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that focus on women and girls are at the table. When working with NGOs in disaster education, training, planning, assessment, and all other efforts, be sure to involve NGOs that advocate for women and other culturally marginal populations (such as the Rohingya in Burma/Myanmar, undocumented migrant workers in Thailand, and so on). Consider these populations specifically, not generically. Each group will be vulnerable in a particular pattern that differs from others.

- Include NGOs that focus on sex workers and trafficking in girls and women. Among both women and migrant workers, sex workers (voluntary and involuntary) are a particularly vulnerable group.

Women are often in different places at different times than men. Their behavior is confined by different strictures. Disaster plans must take all those differences into account—lest not only women but also entire communities end up more vulnerable.

Note

- United Nations (UN) International Strategy for Disaster Reduction, Hyogo Framework for Action 2005–2015: Building the Resilience of Nations and Communities to Disasters (Geneva: UN, 2007), available at <www.unisdr.org/files/1037_hyogoframeworkforactionenglish.pdf>.