II. Women and Conflict Prevention

Measured in lives and livelihoods, stopping cycles of conflict and preventing wars before they occur is the most important way to ensure stability and prosperity around the world. Socio-economic and cultural analyses must inform any effort to forecast and counteract emerging drivers of conflict; examining how risk factors for conflict affect men and women differently improves our understanding of the root causes and consequences of conflict, including vulnerability to mass atrocity. From Kosovo to Rwanda, societies have witnessed rising discrimination and violence against women as early indicators of impending conflict. Tracking and better understanding how these indicators relate to the potential for instability should inform the international community’s best practices in preventing conflict before it begins.

—United States National Action Plan on Women, Peace, and Security

3. Creative Solutions for Crisis Response and Stabilization:

The Power of a Gendered Approach

By Rick Barton and Cindy Y. Huang

I define peace and security in my country as a free Syria, without the regime, without shelling, without extremists, without sectarian [violence]. I want a Syria where women and men are equal inside free Syria. Women will be a part of negotiations, will be a part of transitional justice, women will play an essential role in the first steps towards democracy. . . . Syrian women will play [an] essential role in this.

—Razan Shalab Al Sham, Syrian Emergency Task Force, from an interview conducted as part of the Profiles in Peace Oral Histories Project of the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security, 2013

As you read this book, gender equality—in society at large and in formal and informal political, judicial, and security institutions—is critical to successfully preventing violent conflict and responding to crises. Failing to include women in peace and security efforts results in a shaky, unstable, and partial peace that leaves in place a society’s root causes of violence. In the past two decades, women’s representation in major peace negotiation delegations averaged only 9 percent. Only 4 percent of signatories in these peace processes were women. Today, women still hold fewer than 20 percent of seats in national legislatures and comprise less than one-fifth of cabinet positions worldwide. These facts make it our mission to ask: Where are the women?

Under Secretary for Arms Control and International Security Rose Gottemoeller delivers remarks at Global Zero Conference, Yale University, February 18, 2012 (State Department)

In December 2011, President Barack Obama signed an executive order launching the U.S. National Action Plan on Women, Peace, and Security (NAP), a comprehensive roadmap for accelerating and institutionalizing efforts across the Federal Government to advance women’s participation in making and keeping peace in accordance with United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1325. The NAP’s goal “is as simple as it is profound: to empower half the world’s population as equal partners in preventing conflict and building peace in countries threatened and affected by war, violence, and insecurity.” One of the major innovations of UNSCR 1325 and resulting action plans is to take a holistic view of women’s roles. Too often, women are viewed solely as victims of war and conflict rather than agents for peace and security.

The U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations (CSO) takes a leading role in preventing and minimizing conflicts through the inclusion of women at the onset of conflict. We recognize the link between the status of women and girls and a society’s stability. The CSO mission—to break cycles of violent conflict and mitigate crises—is closely linked with the women, peace, and security agenda. Gender inequalities exacerbate conflict and reduce the potential for peace. Because gender inequalities have historically disadvantaged women and girls, especially in conflict situations, CSO emphasizes advancing their status at all levels of peace and security decisionmaking. By doing so, we are more effective in preventing conflict and responding to crises. At the same time, we recognize that men and boys have specific roles and vulnerabilities in conflict that must be taken into account.

CSO is committed to implementing best practices for gender equality and gender mainstreaming, and although each country engagement has different goals, objectives, and challenges, CSO teams are deployed to countries in crises and are charged with examining each case through a gender lens to recognize and consider particular dynamics in the country and region, promote equality, and advance the status of women and girls where they can. Gender, in contrast to biological sex, refers to socially constructed roles, attributes, behaviors, activities, and opportunities a society assigns to men and women. Gender is context- and time-specific, and is mutable. A gender lens requires looking at a situation from two angles: through one lens, we view the realities, needs, perspectives, interests, status, and behaviors of men and boys, and through the other, we view those of women and girls. Combined, they help us understand gender dynamics and provide a more comprehensive view of a situation or society. Such an analysis shapes our understanding of the underlying causes of destabilizing violence and of how to build resilience that can help prevent and mitigate conflict.

We are working to apply this gender lens to our conflict prevention and mitigation work, both at home and in the field. CSO was the first Department of State bureau to establish a Bureau Gender Equality Policy to institutionalize our commitment to the U.S. National Action Plan on Women, Peace, and Security, making every part of CSO responsible for advancing gender equality and female empowerment, from budget planning to designing in-country engagements. We are still working to fully implement our policy and integrate gender analysis into all CSO operations. As we work toward that goal, we are discovering both the benefits and challenges of making it a priority. We believe the best contribution CSO can make to promoting women’s involvement in peace and security is to give examples of some of our recent efforts, and to offer the lessons learned along the way.

Case 1: Mobilizing Women to Prevent Electoral Violence in Sierra Leone

From 1991 to 2002, Sierra Leone suffered a brutal civil war. It claimed 50,000 lives and displaced 2 million people. Countless women and girls were raped, forcibly “married,” or taken into sexual servitude. While Sierra Leone has made notable progress since the end of the war, the country remains fragile. As the November 2012 elections were approaching, many were concerned that presidential, parliamentary, and local elections could reignite violence. Women were especially vulnerable; fear of violence had deterred many from seeking office or even voting, which undermined progress toward a stable democracy.

In August 2012, the Department of State wanted to take creative action to help Sierra Leone conduct free, fair, and peaceful elections. Embarking on CSO’s first women-focused engagement, we worked closely with the U.S. Embassy, U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and Secretary of State’s Office of Global Women’s Issues (S/GWI) to develop, fund, and carry out several initiatives. “In devising a strategy, we thought we could adapt lessons from recent elections in Senegal and Liberia,” explained the CSO officer leading the engagement. “Women in both countries had been successful ambassadors for peace during their elections, so we decided that engaging Sierra Leone’s women in similar efforts had great potential.” The women-focused plan had two main components: help women advocate nonviolence, both locally and nationally; and help women and election authorities build cooperation.

Locally, we funded work in two high-risk districts by a local organization, Fambul Tok (“family talk” in Sierra Leone’s Krio language). This nongovernmental organization had established the Peace Mothers program, a collection of community-level groups that address women’s unique postwar needs. With support from S/GWI and CSO, Fambul Tok hosted brainstorming sessions with 16 civil society organizations to develop conflict-prevention messages. Fambul Tok used these messages to train 52 female community peace ambassadors to advocate nonviolence, mediate conflict, and enlist electoral and state authorities in efforts to prevent any local conflicts from escalating. These peace ambassadors directly engaged their communities by hosting 38 radio shows and leading 28 football games to promote peace.

Nationally, CSO provided diplomatic support to UN Women’s investment in a Women’s Situation Room (WSR) in Freetown. This early warning and rapid response effort was first launched by women leaders in West Africa in 2011 and was implemented successfully, first in Liberia and then in Senegal. The goal was to work with women and young people to mobilize in order to prevent electoral violence, promote nonviolent commitment, observe elections, gather and analyze information about conflict, and respond rapidly and informally to deescalate any threats or to urge the appropriate authorities to take action. Using the theme “peace is in our hands,” the Sierra Leone WSR deployed more than 300 observers across 14 districts, including in Fambul Tok’s focus areas of Kono and Kailahun. Diplomatic support through visits by the U.S. Ambassador and a statement of support by then–Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton increased national media attention and shined a spotlight on the women’s advocacy of nonviolence.

Sergeant Michallie Wesley, USA, answers question during an interactive discussion on the theme of “Women Serving in Combat” at Camp Liberty, Iraq, March 2011 (U.S. Army/Jennifer Sardam)

Also, CSO partnered with a USAID police advisor to help women and police build relationships before the election to ensure that early warning and response mechanisms would work effectively. For instance, Fambul Tok invited police to their community dialogues and sponsored open discussions on how the police could better respond to the needs of women in their communities. In some cases, this was the first positive contact rural women had with police. To strengthen women’s relationships with police, Fambul Tok also partnered with the Office of National Security. As a community member told the program manager, Fambul Tok did so to “make sure that the police know it is not just about supporting elections. If the community is peaceful, the district will be peaceful, as will the nation. Women are the linchpin.”

On November 17, 2012, Sierra Leone held its most peaceful election since the end of the civil war in 2002. Nearly 90 percent of the country’s 2.7 million registered voters participated. While the political party that lost raised issues about the balloting, violence was limited. Though CSO was only one of many actors, our engagement review found evidence that our partners effectively spread peace messaging and mediated conflicts that were at risk of escalation.

CSO learned in Sierra Leone that a relatively small-scale undertaking can have a significant impact by working through existing local networks. Traditionally, host country partners tend to be urban but well known. CSO is finding that, beyond the nation’s capital, there is a treasure trove of undiscovered and nontraditional leaders and volunteers, many of whom are women.

Case 2: Engaging Women and Men in Ending Gang Violence in Honduras

In Honduras, CSO is helping counter a gang-driven homicide crisis. In May 2013, as part of that effort, we helped launch Mujeres Unidas (Women Together), a group of women who have lost loved ones to violence. The goal is to raise awareness among women that they have a voice, their loved ones are not forgotten, and the government needs to bring justice to each case.

This group was not created, however, until CSO engagement in Honduras was nearly a year old. In trying to mobilize citizen action, the initial photos, video, and strategic messaging we used proved too graphic. “That may work for men, but women do not tend to be motivated by the sight of dead men on pavement,” we were told by a local Honduran woman in response to an initial “Stop the Violence” campaign ad that portrayed a slain young man lying in the street. Through structured interviews, surveys, and focus groups with locals, we learned that women tended to recoil from the original poster, envisioning their husbands and sons as the ones slain. Interestingly, we also found that men distanced themselves from the image through feelings that the victim must have done something to deserve it.

With that insight, we worked with our partners to change the strategic messaging to a photo that emphasized “No more insecurity” on public transportation. The purpose of the campaign was to build trust between the community and police in a positive and empowering manner. The focus groups and interviews conducted to gauge the campaign’s effectiveness revealed that the tone and presentation of images and language had significant bearing on how content was received. Focus group participants gave higher credibility ratings to softer tones and female voices and persons. The new poster was widely popular and accepted in the Stop the Violence campaign, which ran from March to June 2013. At the same time, through focus groups and work with partners, CSO observed a sense of powerlessness and lack of agency experienced by families and friends who had lost a loved one to violence. Public discourse was more focused on the death of the individual and the violent act rather than on what survivors could do to heal and honor the memory of the loved one. From our communications research we knew that women would be considered effective messengers and that victims of violence were feeling isolated. CSO supported local activists to form Mujeres Unidas to respond to this need.

At the event announcing the launch of Mujeres Unidas, more than 100 women arrived carrying photos of their deceased loved ones and with banners demanding government action. The media came out in force; there were about 10 television cameras, including some from Mexico and Costa Rica.

Supporting this campaign taught us that information and analysis for engagement design must pay close attention to gender differences. While the initial messaging was found less effective among both men and women, the impetus to investigate more deeply came from a pattern more pronounced among women’s responses. A gender-sensitive analysis would have given CSO’s Honduras team an early indication of how messages and images would affect female and male audiences, which ones would best mobilize women and men to get involved, and what would benefit the entire community the most.

Case 3: Building Networks of Syrian Women to Bring about and Lead a Peaceful Transition

Responding to the crisis in Syria has been one of CSO’s top priorities. Among other activities, CSO helped produce a variety of workshops on topics including governance, communications, and reducing sectarian strife. In August 2012, soon after the CSO gender policy was released, CSO supported the Center for Civil Society and Democracy in Syria (CCSDS) in holding a workshop in Gaziantep, Turkey, for 20 women as part of the CCSDS “Women for the Future of Syria” initiative. Two Syrian female trainers engaged the participants in discussions about their visions for Syria’s future in the areas of health, education, economic development, and civil society. The women planned projects that they could begin implementing in these fields. One proposal was a march with the theme “Yes to Peace, No to Revenge.”

CSO also supported a series of Planning for Civil Administration and Transition (PCAT) courses for mixed groups of women and men, focused on building the capacity of members of local councils, professional groups, and civil society to plan and coordinate local governance and security. The lead trainer was an Arab woman who encouraged the active participation of Syrian female trainees, most of whom led humanitarian aid and local service delivery in their communities in exercises that included gender-sensitive budgeting and inclusive decision making processes.

During a trip to Istanbul in November 2012, CSO leadership had the opportunity to participate in a roundtable with a diverse group of Syrians, including Sunni Arab, Christian, and Kurdish women. Their main concern was that they would be under-represented in the post-transition political process. Recognizing a significant opportunity to support Syrian women, in May 2013, CSO and its implementing partners held the first women’s four-day PCAT course, in Gaziantep, Turkey. The training enabled women to safely express their key security concerns within their communities, including but not limited to rape, kidnapping, psychosocial and physical trauma, food insecurity, security of female detainees, early and forced marriages, and military strikes. Our experience and findings from this course have informed broader policy discussions, as well as the curriculum for other mixed-gender trainings. In addition, CSO has partnered with the Syrian Emergency Task Force and its field director, a remarkable Syrian woman, to provide training and equipment to dozens of local councils in liberated parts of northern Syria. With this support, the field director has made dozens of trips into Syria, where she has met with civilian and military leaders to advocate for participatory governance and a rule of law system that respects women’s and minority rights.

Finally, CSO is actively involved in supporting independent Syrian media to promote balanced coverage and accountability of all parties. As part of this effort, we funded a professional mentor for Radio Nasaem, a women-owned and -operated independent radio station inside Syria. One of the first programs produced under the mentor’s guidance was a 30-minute interview with a well-known Syrian nurse and mother who spoke of her experiences as a leading opposition activist, caring for the wounded, and serving two periods of detention.

While much more needs to be done to build the capacity of Syrian women to play leading roles in Syria’s transition, CSO’s activities helped catalyze and have contributed to the broader U.S. Government strategy to elevate Syrian women and promote gender equality. The training opportunities have given women from inside Syria a voice in determining local priorities and articulating their vision for a future Syria and building momentum for a more inclusive peace process and transition. Recognizing the gravity of the crisis and the reality that rebuilding Syria’s social fabric and political future will require women’s active participation, CSO will continue to work with our interagency and international partners to help ensure that Syrian women are not ignored or marginalized. Syrian women have articulated a compelling vision of a peaceful and united Syria. With the support of international actors, they are actively mobilizing—locally, nationally, and internationally—to realize that vision.

In the initial phases of CSO’s Syria engagement, we paid too little attention to the importance of women’s participation and the different obstacles they faced. We had not yet fully recognized that it is more difficult for women to travel to Turkey to participate in trainings, both because they often have families to care for and because they are more at risk of sexual violence. As a result, the percentage of women in the initial workshops was low. The women’s PCAT showed us it was possible to support the training of Syrian women outside of Syria through targeted efforts. However, given the increasingly violent and chaotic situation inside Syria, CSO has begun to pursue train-the-trainer options to enable those Syrian women we can reach to train others inside Syria. More broadly, we have learned that despite the dissemination of best practices, promoting the inclusion of women requires consistent leadership within the U.S. Government and constant attention to evolving conflict dynamics.

Case 4: Training Belizean Mediators to Combat Gang Violence

In 2012, CSO was asked to help address gang-fueled homicides in Belize. Our conflict analysis indicated the most promising approach was a combination of mediation and community dialogue. We strived for a diverse group of participants, considering both gender and age. CSO supported three conflict-resolution/mediation courses, which trained 36 mediators, 47 percent of whom were women, and 20 trainers, 75 percent of whom were women, who went on to train many more mediators. Mediations took place with gangs, prisoners, at-risk youth, and community members.

We saw firsthand how gender dynamics make a difference in mediation. In some cases, female mediators are more effective than men in gang mediations dealing with male violence. “Two participants who are female gang mediators said that when gang mediations are really tense, the female mediators can calm down the situation,” recounted a CSO mediation expert who worked in Belize. “The middle-aged females can deescalate more effectively and are able to work through the mediation process because the gang members do not see them as a threat; they respect them as they would a grandmother.”

In January 2013, CSO led a 2-day course on starting, leading, and sustaining community dialogues, which empower citizens to identify and address root causes of violence and instability in their neighborhoods. Most participants were from gang-ridden and impoverished neighborhoods in Southside Belize City, and they have committed to starting dialogues to help build resilience in their communities. Twenty-one of 26 course participants were female, and 9 of the 12 dialogues that have started since the course ended are led by women.

One dialogue brought together women living in poverty with women who found jobs as a result of training programs. They discussed the root causes that keep some women from improving their lives. Another dialogue brought a group of community members together who facilitated an annual “Day of Healing” in gang-ridden neighborhoods to create a new sense of community. A male-led dialogue focused on mentoring young men on “rites of passage” issues specific to men, including male-on-male violence and gang involvement. Addressing this often-neglected “other side” of gender and conflict—hyper-masculinity and men’s roles—is a critical component of supporting women in building peace, and an equally important part of understanding gender dynamics to resolve conflict.

A CSO evaluation team found that mediation was judged by both disputants and mediators as highly effective. Eighty percent of the cases the mediations resolved involved threatened or actual violence, and agreements appear to be holding. Prime Minister Dean Barrow called for extending conflict mediation to every high school in Southside Belize City. The locally driven mediation program will continue to facilitate the training as government agencies, nongovernmental organizations, and Belize City’s high schools build their internal mediation programs. Building on the skills developed and momentum created in the dialogue training, local leaders are working with diverse groups to improve safety in their communities.

CSO’s Belize engagement highlights the imperative to include men and women from many groups to address gang violence and reach at-risk youth. Law enforcement, communities, and social service providers must work together to reduce violence. Our efforts helped increase cooperation and coordination among these groups, which have not always been linked effectively. In addition, our experience emphasized the unique and complementary roles of male and female participants, including the urgent need for more female and male role models for youth.

Private First Class Julia Carroll, one of the first three women to graduate from Infantry Training Battalion, eats small meal after 6-hour patrol near Camp Geiger, NC, October 2013 (U.S. Marine Corps/Tyler L. Main)

Integrating Objectives into Strategies and Responses

Gender analysis is “a tool for examining the differences between the roles that women and men play in communities and societies, the different levels of power they hold, their differing needs, constraints, and opportunities, and the impact of these differences on their lives.”1 For effective conflict prevention and crisis response, a gender analysis should be conducted at the start of strategy development and streamlined throughout the design, implementation, and evaluation phases of conflict and postconflict operations. The importance of conducting an analysis at the start, even a rapid one, was one of CSO’s most important lessons learned from these engagements. One year since the launch of the CSO Gender Equality Policy, we have identified the five areas in need of improvement to effectively integrate women, peace, and security objectives in our work.

Gender Analysis and Assessment Planning. CSO will increase support for rigorous gender analysis when designing country engagements. We plan to systematically provide all teams with simple, concrete questions that can be tailored to the local context and conflict dynamics. These questions are not meant to be exhaustive, but should offer a baseline understanding of community norms and behaviors. Our questions include, for example: “What roles do men and women typically play in a community?” “How does the history and culture of the country contribute to defining these primary roles?” “Who has access to resources and control in the community and why?” “In what way are men, women, and children vulnerable?” In addition, we need to consider assessment team composition and interview design, as well as scheduling to ensure that our approaches generate candid information about gender and facilitate the safe and productive participation of women and men.

Research, Data, and Evaluation. In addition to conducting our own analyses, surveys, and studies, CSO needs to draw quickly on available research and expertise on gender differences and inequalities, as well as sex-disaggregated quantitative and qualitative data, to understand underlying gender dynamics for both strategy and program formulation. We must also devote resources to quality metrics and evaluation, including creating realistic gender-specific targets and goals, gender-specific evaluation questions, and accountability and learning mechanisms at all levels of the organization.

Conflict and Gender-Sensitive Programming. CSO will continue to work with partners, especially local organizations, to design programs that recognize the unique opportunities and constraints men and women face in settings affected by conflict. We must relentlessly ask: “Who will really benefit, and who will be excluded?” In doing so, we need to consider women not only as victims, but also as agents and producers of peace and security.

Leveraging the Role of Local Partners to Integrate Gender Perspectives. CSO firmly believes in transforming conflict and sustaining peace through local ownership and partnership. We have selected host-country partners who are trusted, respected voices of their communities. Leveraging their roles, learning from them, and improving their ability to consider gender dynamics give us better results. We must create an organizational culture where it is our habit and default to look to local partners in the search for effective solutions.

Policy and Program Development. Interagency policy and program development brings its own challenges. In crisis-driven situations calling for rapid response, the gender lens is often forgotten. We focus on getting the equipment to activists in the field quickly, launching a strategic messaging campaign as soon as possible, and holding training sessions on the ground—all before understanding the gender dynamics at play. In doing so, we miss opportunities to be as effective as we could be. If we ask gender-sensitive questions from the beginning, and focus the gender lens before we make policy, we more effectively prevent conflict and respond to crisis. It takes consistent leadership and learning at all levels to ensure that gender-responsive approaches are implemented for increased impact.

Gender integration can be difficult to implement, even with high-level commitment. At the foundation is gender analysis. It takes continued leadership and hard work for policymakers and practitioners to fully appreciate that gender analysis entails more than targeting women; it requires understanding their points of view, considering their different constraints and opportunities, knowing the strength of their informal and formal networks, analyzing the gendered responses their involvement could bring, and asking how gender roles constrain and shape men’s behavior as well. Gender analysis is essential to understanding the conflict, looking at conflict and violence holistically, and getting the response right.

Perhaps the greatest lesson that CSO has learned in a year of implementing our gender policy is that nothing replaces a culture and spirit of learning together through study of best practices, training, and, most important, learning through experience. This combination of commitment and action from all levels of the organization is at the heart of gender mainstreaming and institutional change.

From Policy to Practice: Advancing Objectives on the Ground

CSO remains fully committed to advancing gender equality and women’s participation in efforts to break cycles of violence and mitigate crises. We will continue to proactively engage women and girls in our engagements, including promoting the participation of women in host government conflict prevention and security policymaking, supporting women’s coalitions and local and national women leaders, and conducting gender-sensitive conflict analyses.

In the future, we must do a better job reframing the narrative and strategic approach of those we identify as leaders and key actors. Women are too often viewed as victims, not as the powerful agents of change that they are. Women are also sometimes combatants and peace spoilers. It is critical that their roles in and perspectives on conflict are recognized and addressed. Most important, failing to fully consider half the population leads to partial and unsustainable peace that does not address the root causes of violence. Successful conflict prevention, management, resolution, and political transformation strategies must not only include women, but also recognize the ways in which conflict affects women and men differently.

The authors would like to extend their gratitude to CSO Gender Team Leads and contributing authors Jennifer Hawkins and Cynthia Parmley, to Ben Beach for editorial assistance, and to CSO Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary and Senior Gender Advisor Ambassador Pat Haslach for her vision and leadership.

Note

- U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), Gender Equality and Female Empowerment Policy (Washington, DC: USAID, March 2012), 12.

4. Security for the 21st Century:

Preventing Conflict by Building Strong Relationships and Stable Communities

By James G. Stavridis and Scott T. Mulvehill

Peace is not just ceasefire in the country. Peace is having all kinds of security and trust. Security is very much related to freedom [including] economic freedom.

—Ela Bhatt, Founder of the Self-Employed Women’s Association of India, from an interview conducted as part of the Profiles in Peace Oral Histories Project of the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security, 2012

Winston Churchill once stated, “The problems of victory are more agreeable than the problems of defeat, but they are no less difficult.” If we could add to Mr. Churchill’s comment, we should state that preventing conflict may be the most challenging—and important—of all our endeavors. The heavy cost of failing to prevent conflict in Europe during the 20th century—millions of lives destroyed and cities ruined—cannot be borne again by any country or alliance. Conflict brings other challenges as well: displaced populations, shortages of basic food items or even starvation, increased instances of sexual and gender-based violence, destruction of infrastructure, and weak rule of law.

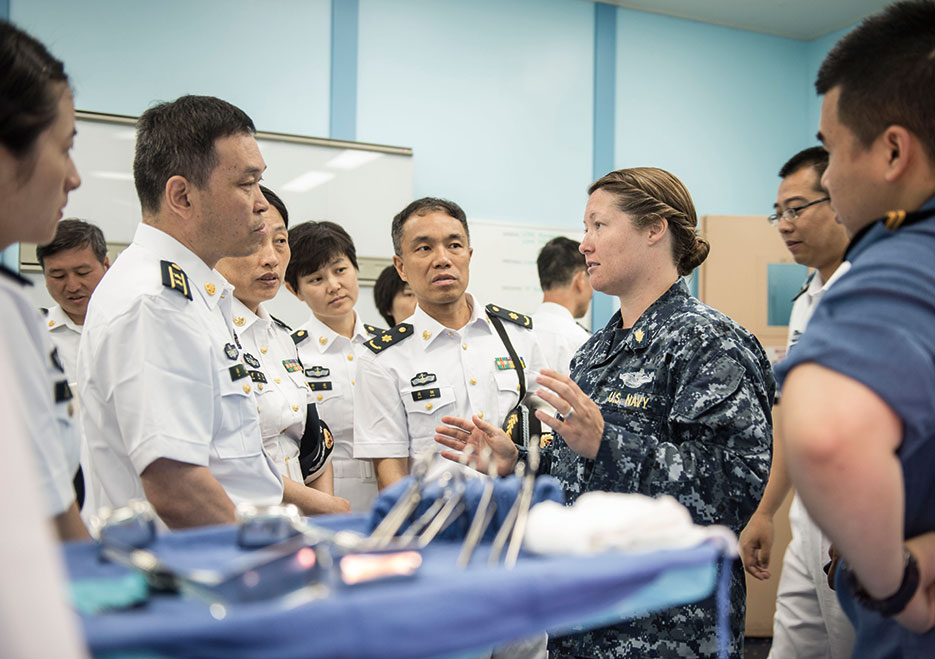

Lieutenant Jessica Naranjo, USN, speaks to People’s Liberation Army Navy medical personnel from hospital ship Peace Ark (T-AH 866) during tour of Military Sealift Command hospital ship USNS Mercy (T-AH 19) (U.S. Navy/Justin W. Galvin)

Today, U.S. European Command (USEUCOM) is working to support enduring stability and peace in Europe and Eurasia by engaging in areas that have been affected by conflict or that live under the threat of its reemergence. Preventing conflict is best accomplished through a “comprehensive approach”1 to social, economic, and security development within communities, and ultimately within nations. By combining the resources and expertise resident within governmental, private, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), we are best able to promote stability. Communities succeed when they have adequate education and healthcare, when employment opportunities are available, and when the government is able to provide security and legal systems. A lasting and sustainable peace starts with these elements. Preventing conflict is as important a mission as prevailing in conflict and, by the way, vastly less expensive.

A fundamental objective of our security policy is to develop a culture of respect for human rights that will facilitate these systems. Such respect, however, has not always existed. Historically, the military commander’s sole concern had been to vanquish the enemy militarily and to impose political will. But in the 19th century, the concerns and legal obligations for military commanders began to change. The Geneva Conventions and the founding of the Red Cross were some of the earliest steps taken by nation states to limit suffering, acknowledge the plight of innocent civilians in conflict, and address what is morally acceptable in warfare.

Henri Dunant, a Swiss businessman and social activist, witnessed the Battle of Solferino (in modern-day Italy) in June of 1859. He saw the death of some 40,000 people amid a near-complete lack of medical care. Dunant was so moved by the sight of such suffering that he wrote and published A Memory of Solferino—at his own cost—recounting what he saw that day. He proposed establishing a relief agency for humanitarian aid in times of war that would remain neutral during the course of any conflict. His efforts were the inspiration for the International Red Cross and Red Crescent. The Geneva Conventions were established to insist upon respect for human life and rights during war. These initiatives began to change how commanders waged war, and they broadened the way society views the causes of and solutions to conflict.

Upon this foundation, we have the ability to address causes of conflict and prevent the outbreak of hostilities. We have numerous inter governmental and non organizations that strive to limit suffering in conflict and protect human rights. The challenge is to effectively coordinate efforts as we work together to address and prevent circumstances that lead to conflict.

Building Basic Human Well-Being

Our work at U.S. European Command is regionally focused on Europe and Eurasia. The inherent geopolitical density of this region makes it a challenge to address the myriad issues that cross borders. The solution we have adopted is an inclusive model for our operations. To inform our perspective on the security needs within the region, USEUCOM actively cooperates with international organizations, NGOs, private companies, think tanks, and the local populace to address the conditions that can lead to conflict. For instance, USEUCOM hosted François Bellon, the Head of Delegation of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), to both the European Union and North Atlantic Treaty Organization. He commented that we are in the same river, but in different boats.2 Our organizations face the same reality, even as we see it from differing perspectives. USEUCOM is designed to address problems from a military aspect, whereas the ICRC addresses problems from a humanitarian one. Thus, creating and maintaining a functional relationship are essential.

USEUCOM recognizes the importance of maintaining and strengthening relationships—not only individually but also military-to-military, between governments, and among affiliated organizations. Our decisionmaking process is informed by that far-reaching network of relationships, touching on the best ideas and experiences of the full range of academia, private industry, and governmental organizations. Much of this is done through the USEUCOM Interagency Partnering Directorate, which facilitates our interactions with the numerous U.S. Government agencies that are focused on providing security and preventing conflict. We consider these relationships so important that we have placed agency liaisons within USEUCOM headquarters. Every day, headquarters staff members work side by side with representatives from the Departments of State, Energy, Treasury, Justice, the Drug Enforcement Administration, Customs and Border Patrol, U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Working with these organizations—and more importantly, working in close contact with their people daily—allows us to forge our friendships and build relationships. As a result, when we face challenges and crises, we are able to execute more effectively as a team that has already trained together. We have found that the diverse perspectives that these organizations bring to USEUCOM’s operations allow us to make decisions and policies that are more inclusive and to consider probable second- and third-order effects.

When conducting military operations, a well-known saying is to “know your limits”—in other words, to know what is achievable and what is not. The Department of Defense is very good at many tasks, but it does have its limits. To increase our ability to manage complex problems, and to broaden the limits of what is achievable while trying to solve problems, we have found it best to partner with organizations that can help us create security and stability in a comprehensive way. To do this, we support organizations that are best suited to provide access to healthcare facilities, schools, critical infrastructure, and economic opportunities to our partner nations. By taking a whole-of-government approach, we seek to solidify regional security.

USEUCOM draws from the experience of those living in the communities in which we operate. We seek out and rely on myriad perspectives in the communities affected by conflict. Women in these areas offer unique and valuable viewpoints. Hearing their stories, their needs, and their ideas has allowed us to focus on issues that are most important to them. Pursuing the underlying issues within the community, which may not be obvious to the newly arrived military member, will allow us to more quickly provide a stabilizing presence while respecting human rights. By expanding our perspectives and striving to create an inclusive planning environment, we find solutions that best fit the challenges facing communities and are able to address them before they become destructive.

If our planning fails to provide opportunities and solutions for inclusive security, communities face a situation that invites criminal and terrorist activities. If the government cannot or will not provide security, these organizations can take root and become extremely difficult to remove. Poverty, ethnic divisions, frustration with the failings of the government to provide critical infrastructure—all are reasons criminal networks can flourish and thus destroy whatever security a community had known.

USEUCOM helps build stability within the region by combining efforts to develop education, healthcare, and security systems for conflict-affected communities—all of which are particularly important to girls and women.

Universal Education and Economic Growth

Ensuring access to education is an important part of building regional stability and, ultimately, security. In Azerbaijan, for example, USEUCOM is partnering with the Taghiyev Initiative Young Women’s Entrepreneurship Center to establish a school to teach job skills for several hundred girls, thereby offering education and economic opportunities for the community’s women.

Hillary Rodham Clinton has stated, “Whether it’s ending conflict, managing a transition, or rebuilding a country, the world cannot afford to continue ignoring half the population.” Her comments point out our need to use the intellect and energy of women to improve societies. As we educate and empower these women, who until now had not been able to enter the workforce, the community’s pool of talented, productive individuals will effectively double and allow for marked economic growth. The investments we make in education and employment opportunities will pay off with stability in communities—and then regions—as economic growth and development take hold.

Similarly, our investments in the region’s children will have a lasting legacy. In Macedonia, for instance, in collaboration with that government and USAID, we are supporting a 4-year, $300,000 project to incorporate teaching about ethnic tolerance and respect for others into classroom instruction. Schools are recommended for renovation projects based on their performance with the curriculum. This interagency approach to advancing human rights and tolerance to children should bolster the region’s security for years to come.

Hawa Mamoh (left), a Sierra Leonean officer with African Union–United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur, with Zara Adam, one of the displaced at Zam Zam internally displaced persons camp near El Fasher, North Darfur, Sudan (United Nations/Albert González Farran)

Healthy and Stable Communities

Our integrated strategy in the pursuit of regional stability is based on a shared goal: to develop our partners’ abilities to independently prepare for, prevent, and, when needed, respond to challenges. That includes helping offer access to healthcare providers and facilities throughout the region. USEUCOM strives to provide the expertise, capacity, and relationships to meet this challenge through our comprehensive approach. By coordinating our efforts with our partner nations, other U.S. Government agencies, and NGOs, we train and empower communities to meet their healthcare needs.

Another initiative that has produced tangible results for more than 20 years is USEUCOM’s State Partnership Program. Today, 22 European nations are linked with U.S. military units. The varied expertise and resources provided by the individual units are an effective “force multiplier” for USEUCOM. This robust array of capabilities provides more engagement options as we manage our partnerships. Its efforts go beyond what most people ordinarily think of as military endeavors. For example, the state of North Carolina and the Republic of Moldova have enjoyed an ongoing partnership under this program since 1995. Recently, a team of dentists from the North Carolina National Guard and University of North Carolina traveled to Moldova to provide free dental care to more than 300 children. Access to this vital care serves to increase the health of the communities and provides a source of stability.

As part of a recent USEUCOM healthcare engagement event, U.S. Navy corpsmen and medical experts trained host nation medical providers as they performed preventive health screenings and medical examinations to Romanian women. Providing prenatal care and reducing maternal mortality increases the life expectancy of a community and ensures family vitality. In addition to checking vital signs and conducting breast exams, pelvic exams, and Pap smears, these medical professionals discussed basic wellness measures to educate and prevent further medical issues within the community. By training the local care providers, USEUCOM has helped establish a lasting knowledge base that will benefit future patients—and the community.

Preparing for Disasters and Offering Humanitarian Support

Another way USEUCOM helps stabilize the region’s communities is through the command’s humanitarian assistance and disaster relief programs. These programs not only provide security but are also designed to build partnerships while increasing the capacity of partners to handle disasters. The USEUCOM role is most often that of facilitator between the host nation and the participating agencies and organizations, which helps empower partner nations, so they can better handle emergencies and enhance their civil response force and critical infrastructure. In this supporting role, we provide onsite experts, training, transportation, rehabilitation and construction, and donations of excess equipment to communities in most need. By assisting in the development of critical infrastructure, emergency plans, and preparations, we are helping communities and local governments to more rapidly and effectively respond to disaster. These efforts ensure local crises are contained and do not affect regional security. USEUCOM’s humanitarian efforts are funded through overseas humanitarian disaster assistance, civic appropriations, and our own operation and maintenance funds.

As the United States enters a time of fiscal constraint, it is important to realize the high impact that such relatively small investments have in our region. Our humanitarian assistance and disaster relief projects provide some excellent examples. USEUCOM funded 77 projects in 19 countries in 2011, which totaled $14 million. These projects varied from providing flood relief in Serbia, Albania, Moldova, and other Eastern European nations to renovating 44 schools and 28 hospitals and clinics throughout Eurasia. Working with our intergovernmental organizations, NGOs, and agency partners, we performed equipment upgrades to 33 emergency services locations (including, but not limited to, fire stations, ambulances, hospitals, and clinics) and to water infrastructure. By ensuring that areas have essential services that work both during peacetime and during crises, we will be better able to mitigate disaster impact and assist in efforts to help affected areas return to normalcy.

The benefits of such support can extend beyond normal operations as well. Latvia was able to send firefighters and equipment to fight forest fires in Russia and assist Poland and Moldova during severe flooding. This new capability resulted from a USEUCOM project that assisted Latvia in modernizing eight fire and rescue stations. Enhancing their essential service capabilities allowed Latvia to become a provider of help when it was needed—thereby lessening the burden on neighboring countries. USEUCOM efforts support diplomacy and development, thus helping create security.

Clearly, none of these is our main effort. We remain focused on our principal and traditional role in ensuring U.S. military security forward. But we do help support the American effort to wield smart power.

Criminal Threats

When a nation has a healthy and functioning infrastructure, a variety of NGOs can rapidly cross borders to lend aid. But so can criminal networks, which are similarly able to work across many jurisdictions. As our world becomes more connected, we face a greater variety of threats. That is why, in addition to facing traditional military challenges, USEUCOM helps the region address complex threats from both state and nonstate actors. In parts of the region that are especially troubled by narcotics and human trafficking, USEUCOM’s interagency and international partnering has helped boost security.

Human trafficking destroys communities, harming women and children disproportionately. When an area lacks economic and educational opportunities, trafficking is more likely to flourish, feeding the world’s insatiable demand for cheap labor and the continuing market for sexual exploitation. Intercepting traffickers and their victims is made more difficult as borders are easily transited and as corrupt officials at checkpoints can render useless the laws that exist. These crimes produce substantial profits for the offenders, who can then dispense some of those profits, thus wielding undue influence and undermining those who wish to enforce legislation. Such illicit funds—from both narcotics and trafficking—can support terrorism and can undermine fragile democracies and governments, creating insecurity and threats.

Many organizations and laws exist to fight trafficking, including the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime; Office of the Special Representative for Combating the Traffic of Human Beings; Convention against Transnational Organized Crime; Protocol to Prevent, Suppress, and Punish Trafficking in Persons; and Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea, and Air. Coordinating efforts among the units, organizations, and countries fighting this crime is doctrinally and logistically challenging, and linking their efforts and expertise has not been easy. In an effort to help overcome these obstacles, and to more effectively counter this transnational threat, USEUCOM created the Joint Interagency Counter Trafficking Center in 2011 by leveraging existing counternarcotics authorities and personnel. The center coordinates across the organizations involved in preventing and prosecuting this crime while building partner nation capacity to detect, monitor, and disrupt trafficking events. Combating drug and weapons trafficking allows us to combat human trafficking because so many of the same people and routes are involved.

Our prevention efforts help keep the number of trafficking victims to a minimum. But USEUCOM also helps those who were victims of trafficking by supporting and advocating for their rights to help stabilize the affected communities and normalize victims’ lives. For instance, in 2011, USEUCOM partnered with the Missing Persons’ Families Support Center in Vilnius, Lithuania. This center is an NGO that provides assistance for victi ms of human-trafficking and forced prostitution, as well as for relatives of missing persons. USEUCOM donated excess property from bases that were closing and performed renovation projects for the center. Similarly, the command is renovating the Centers for Victims of Domestic Violence in Bulgaria and Kosovo. Because of these projects, trafficking victims and victims of domestic violence have support as they come back to their communities and their lives.

Furthering the Rule of Law

To be fully effective in our pursuit of security, we must support transparency in public institutions, especially judicial systems, and we must find and prosecute human rights abusers. USEUCOM does this through our Legal Engagement Program, in partnership with the U.S. Defense Institute of International Legal Studies, George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies, a joint effort between the United States and Germany, and each nation’s own programs. USEUCOM, its legal staff, and partner force providers are working with European Ministry of Defense policy and legal experts to promote the rule of law in Europe and to support the International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan and United Nations Peacekeeping Operations during deployments. Our interaction during the USEUCOM International Legal Conference and other regional events has significantly sharpened our partners’ ability to work with other European nations. This has raised the level of awareness and expertise on human rights concerns, rules on the use of force, detainee affairs, operations law, and the importance of civilian control of the armed forces. Additionally, USEUCOM is closely partnered with the Department of Justice and USAID on their judicial/prosecutorial training, counter-corruption programs, and rule of law initiatives to maximize our impact on our partners’ governments. These engagements ensure that the U.S. Government speaks with a consistent voice to civilian and military authorities on these critical priorities as we help provide stability in our region.

Stronger Together

U.S. European Command cannot achieve regional stability and security on its own, or even with the assistance of the Department of Defense and Department of State. Only through our combined efforts and in close coordination with our allies, international partners, private entities, and governmental and nongovernmental organizations can we meet the 21st century’s complex challenges. USEUCOM has taken a comprehensive approach to the social, economic, and security development within this region’s communities, which is the key post–World War II trend in the 51 nations of the European region. Our combined initiatives support the U.S. interagency approach. They help provide education and healthcare, make employment opportunities available, and ensure security and legal systems function fairly in this region. These efforts are aiding in the prevention of conflict in an area that has known many wars. Continued engagement with at-risk communities is essential to securing a peaceful future. As our command motto sums it up, we are truly stronger together.

Notes

- Comprehensive approach is a term used by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) to indicate that all elements of an organization’s influence are brought together. These include diplomatic, information, military, and economic power. Government agencies work alongside private, business, and nongovernmental organizations to combine resources as they work on the most challenging issues. See NATO, “A ‘Comprehensive Approach’ to Crisis Management,” available at <www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/topics_51633.htm>.

- See Mike Anderson, “Words and Swords,” April 23, 2012, available at <www.eucom.mil/blog-post/23295/words-and-swords>.

5. NATO’s Commitment to Women, Peace, and Security

By Mari Skåre

United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 is a powerful appeal to protect those who are most vulnerable in conflicts and their aftermath, and to enhance the participation of women in building peace and security. I very much value the strong commitment by the U.S. Government to implementing this landmark resolution.

—Anders Fogh Rasmussen, 12th NATO Secretary General

It has been more than 12 years since the adoption of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 (UNSCR 1325), and we are still far from reaching its objectives of full inclusion of women in conflict prevention, management, and resolution. We need to continue to educate and raise awareness on how conflict often affects women and men in different ways. Women continue to be vulnerable in conflict, and we are still witnessing sexual violence used as means of war.

Assistant Secretary General for Public Diplomacy Ambassador Kolinda Grabar-Kitarovi, the first woman ever appointed Assistant Secretary General of NATO, speaks at Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies of The Johns Hopkins University, Washington DC (NATO)

Ensuring implementation of UNSCR 1325 and related resolutions requires continued leadership. First and foremost, nations need to step forward; the responsibility for implementing these resolutions rests with national governments. At the same time, international organizations need to make a strong and sustained effort. The United Nations is in the lead when it comes to setting norms and principles, developing overall policies, assisting nations, and keeping them accountable. But as a security organization strongly anchored in common values—freedom, democracy, human rights, and the rule of law—the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) also has a critical role. NATO’s 28 member nations have expressed their strong commitment to protecting and promoting women’s rights, roles, and participation in preventing and ending conflict. While states and intergovernmental organizations must show leadership in advancing this agenda, civil society plays an important role in leading opinion, contributing information, and holding us accountable.

The Alliance recognizes the important role women play in enhancing security and preventing and ending conflicts. We will do our part promoting the inclusion of women as well as integrating a gender perspective in policies and activities. My mandate, as the NATO Secretary General’s first Special Representative for Women, Peace, and Security, includes coordinating and raising awareness of our policies and activities in these areas within NATO and with partners and other stakeholders.

Developing Policy

NATO’s wider policy objective is to build and maintain sustainable peace and security, and our approach to UNSCR 1325 and related resolutions has been developed with that in mind. We want to prevent armed conflicts, but where a conflict does occur, we need to have a complete understanding of the conflict and of its gender dimensions. We need to ensure that a conflict does not have disproportionate impacts on women and children; therefore, we need to facilitate women’s participation.

When developing its overall approach on the agenda, the Alliance has looked at the role of women in peace and security in a comprehensive way, asking what we can do on our own, what we can do to help others, and what others can do to help us. NATO’s engagement in implementing UNSCR 1325 and related resolutions has emerged from our consultations with partners in the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council (EAPC) where our overarching policy on UNSCR 1325 and related resolutions has been developed. This policy was adopted in 2007 and has since been revised biannually.1 The policy’s key points are 1) conflicts affect men and women differently, and 2) we need to involve women more in conflict prevention, management, and resolution. By actively supporting more participation from women at the highest levels, both within and outside the Alliance, we can give them a greater role in building security, resolving current crises, and preventing future instability. We are also keen to see more women participate in NATO operations and missions at all levels of command in our armed forces.

At subsequent NATO summit meetings, we approved a number of NATO statements and communiqués that aim to further define Alliance policy and outline responsibilities. For example, at our NATO Summit in Lisbon in November 2010, we agreed on the first NATO Action Plan aimed at mainstreaming the provisions of UNSCR 1325 and related resolutions into NATO-led operations and missions, Alliance training and doctrine, and all relevant aspects of NATO’s tasks.2 Since 2010, the action plan has been updated, and a strategic progress report on implementation was delivered at our NATO Summit in Chicago in May 2012. On the same occasion, heads of states and governments took a strong stance on the need to ensure continued implementation and integration of gender perspectives into Alliance activities.3 These official, unanimously agreed texts4 represent an important body of NATO policy on the role of women in peace and security.5

We continue working together with our 22 partner countries in the EAPC as well as with many other partner nations that contribute to our missions and operations. At the same time, we also engage with other international organizations, including the United Nations, Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), and European Union (EU), as well as with civil society and the community of nongovernmental organizations, to see how we can complement and reinforce each other’s efforts.

Colonel Shafiqa Quarashi, Afghan National Army, greeted by Brigadier General Anne F. Macdonald, assistant commanding general, Afghan National Police Development, Combined Security Transition Command–Afghanistan, upon Quarashi’s return from the United States where she received a 2010 International Woman of Courage award from Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton (U.S. Navy/David Quillen)

Training and Education

Experience has shown that training and education are strategic tools to help security forces better integrate a gender perspective as well as to reform national defense and security sectors. We cooperate with partner countries and other international organizations to refine and enhance training. Allied Command Transformation (ACT), NATO’s strategic command in Norfolk, Virginia, helps NATO develop and implement training and education tools. ACT works to ensure that a gender perspective is integrated throughout the curricula of NATO Training Centres and Centres of Excellence, and throughout the trainings offered to all personnel, men and women, before they deploy on NATO-led operations and missions.6 To enhance gender training, the Nordic Centre for Gender in Military Operations, based in Stockholm, Sweden, has been designated Department Head for gender education and training for NATO-led curricula.7 It provides recommendations to member nations on how to integrate a gender perspective into education, training, and exercises.

Although the Alliance has no direct authority over measures agreed at national levels, we do require that personnel deployed on NATO-led operations and missions and serving within our structures are appropriately trained and meet certain standards of behavior, as stated in a directive issued by the Supreme Allied Commander Europe and Supreme Allied Commander Transformation on August 8, 2012.8 The directive ensures that UNSCR 1325 and related resolutions are implemented in all operations. It calls on NATO forces to have proper training before deploying and to ensure that proper expertise on gender is deployed in the field. According to the directive, NATO forces must uphold and adhere to high moral and human standards; therefore, any form of abuse, exploitation, or harassment should never be accepted. Several allied nations have initiated gender-related training for subject matter experts and for their armed forces to raise general awareness of UNSCR 1325 and related resolutions ahead of national force deployments.

Engagement in Afghanistan

NATO’s engagements in Afghanistan in particular, as well as in Kosovo, have been transformative experiences for the Alliance in many ways, including in our understanding of the role that women can play in conflict resolution and peace-building. Alongside the rest of the international community, NATO has attached the highest importance to protecting and empowering the Afghan population, including women and girls. The Alliance has emphasized the need for Afghanistan to fulfill its own commitments in protecting human rights and particularly women’s rights.9 In helping Afghanistan stand on its own feet and making sure that it will never again be a safe haven for terrorists threatening our nations and populations, we have steadily kept respect for women’s rights an integrated part of our activities.

For several years, gender advisers have been deployed with the NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF). To quote former ISAF Commander General John Allen, “Advancing women’s rights in Afghanistan is key to preventing the Taliban from reimposing a radical form of Islam once most foreign troops leave by the end of 2014.”10 In 2012, General Allen established a gender adviser position with the rank of general, showing the increased commitment and recognition for this role. Drawn from the military forces of several ISAF countries, these gender advisers are key in helping commanders at all levels take gender perspectives into account when formulating their operational strategies.

A large number of the Provincial Reconstruction Teams across Afghanistan employ gender field advisers as well. These dedicated people provide additional ways for communicating with local communities. They help build trust and confidence in ISAF and advise commanders to the specific needs and role of women and girls in local communities, such as ensured access to basic services, healthcare, and education. Integrating a gender perspective in operations is a matter of leadership and competencies.

A number of countries taking part in the ISAF mission have made a point of deploying female soldiers and officers. Experience has shown that all-female teams, or female soldiers who are part of mixed teams, are well suited for certain security roles, such as house inspections and searches of women. They are also better able to engage Afghan women in discussing security and other concerns.

In the spring of 2013, NATO and its ISAF partners gradually handed over the lead responsibility for security to the Afghan people. Afghans will assume full responsibility for the security of their entire country by the end of 2014. At that point, the ISAF mission will end, but NATO’s commitment to Afghanistan will continue. Together with several of our partners, we are planning a follow-on mission to train, advise, and assist Afghan security forces beyond 2014. As part of this work, we will continue to deploy female soldiers, gender advisers, and gender focal points in operations and promote the importance of including gender perspectives and human rights as we assist in training Afghan security institutions. We are also supporting the recruitment, training, and retention of women to the Afghan National Security Force. These women are role models and deserve our deepest respect and recognition.

Female members serving with Ghanaian battalion of the United Nations Mission in Liberia on patrol in port city of Buchanan (United Nations/Christopher Herwig)

NATO’s Way Ahead

Many organizations have a stake in the women, peace, and security agenda and bring important assets and expertise. We all have an interest in avoiding unnecessary duplication, enhancing best practices, and identifying synergies, thereby achieving results. To that end, NATO has been working in close concert with the United Nations, partner countries, and other international organizations to learn, share experiences and best practices, and raise awareness of the importance of integrating a gender perspective in daily activities. NATO attaches particular importance to deepening its partnership with the United Nations in implementing UNSCR 1325 and related resolutions, as the UN is the custodian of the resolutions on women, peace, and security. Respect for women’s rights and the inclusion of women will require a broad set of reforms that actors other than NATO are better suited to support.

Greater openness and transparency will be essential. Thus, we are conducting a mapping exercise on gender-related education and training activities in NATO, EU, OSCE, UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations, and UN Women, which is the UN entity for gender equality and the empowerment of women. The results of this exercise, and our continuing commitment to share other relevant information, are important for the success of our common endeavors.

The Alliance has partners on five continents, and we are keen to continue to deepen and broaden the agenda on women, peace, and security with this vast network. As we continue to engage partners, we encourage the inclusion of women, peace, and security–related goals in our cooperation programs.

Through its operations and missions, NATO has already learned that fully engaging women and paying attention to both men’s and women’s social roles can improve our understanding and awareness of any conflict or its aftermath, thereby increasing our operations’ effectiveness.

NATO Secretary General Anders Fogh Rasmussen addresses conference on Women, Peace, and Security organized by Security and Defence Agency at the European Union, Brussels, January 2010 (NATO)

Together with our operational partner nations, we attach great importance to incorporating a gender perspective at every stage of operation and mission planning, exercise, and conduct. To this end, a gender perspective is now included in a growing number of NATO planning directives and related documents, including handbooks, codes of conduct, standard operating procedures, exercise scenarios, and tactical manuals. For example, we are beginning to integrate a gender perspective in exercises for understanding how a conflict can manifest itself differently for men and women due to their social roles, and what this means for planning and executing a crisis management operation. The next Crisis Management Exercise includes—for the first time—considering a gender perspective as one of its objectives. We will continue to strengthen this approach.

To assess what has been done to date, we have undertaken a review of the practical implications of mainstreaming UNSCR 1325 and related resolutions into NATO-led operations and missions, led by the Nordic Centre for Gender in Military Operations, with contributions from several operational partners. Focused on our engagement in Kosovo and Afghanistan, this review, when complete, should help us refine future policies, action plans, and military guidelines. It should also assist in developing a more accurate, NATO-wide process of reporting, monitoring, and evaluating the effects of operations and missions.

As individual nations are best placed to put UNSCR 1325 into action, national planning instruments (action plans or strategies) have become key tools in the women, peace, and security agenda.11 Such plans help nations set targets and ensure a systematic approach in reaching those targets. I encourage Allies and partner nations to continue to share information on their national action plans and other national initiatives, as well as to share best practices. This kind of transparency should allow us to learn from each other and complement and reinforce each others’ efforts.

To meet the complex global security challenges of the 21st century, we need to take advantage of the competencies, experiences, and abilities of women and men. Today, the number of women employed in NATO member nations’ armed forces varies greatly. In some NATO forces, the percentage is close to 20 percent, while in others it is much less. By facilitating the exchange of information and best practices among Allies on recruiting and retaining women, NATO will continue to help advance the implementation of UNSCR 1325 and related resolutions.

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization has already made significant progress in implementing the goals articulated in UNSCR 1325 and related resolutions. The Alliance continues to advance the women, peace, and security agenda at every level, including through policies and activities, by making greater use of the potential that women offer in political and military ranks, and by improving cooperation with partner countries and other international organizations.

Notes

- North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), “NATO/EAPC policy for implementing UNSCR 1325 on Women, Peace and Security, and related Resolutions,” June 27, 2011, available at <www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/official_texts_76395.htm>.

- NATO, “Lisbon Summit Declaration,” November 20, 2010, para. 7, available at <www.nato.int/cps/en/SID-22FE2F85-F97249F1/natolive/official_texts_68828.htm>.

- NATO, “Chicago Summit Declaration,” May 20, 2012, para. 16, available at <www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/official_texts_87593.htm>.

- All texts available at <www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/official_texts.htm?keywordquery=Women&search=true>.

- NATO, “Chicago Summit Declaration on Afghanistan,” May 21, 2012, in particular para. 6, available at <www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/official_texts_87595.htm>.

- See NATO, “Bi-Strategic Command Directive (BI-SCD) 40-1: Integrating UNSCR 1325 and Gender Perspective into the NATO Command Structure,” August 8, 2012, particularly sections 2-7 and 2-9, available at <www.nato.int/nato_static/assets/pdf/pdf_2009_09/20090924_bi-sc_directive_40-1.pdf>.

- Swedish Armed Forces, “NCGM established as NATO Department Head,” February 28, 2013, available at <www.forsvarsmakten.se/en/News/Newsarchive/Swedint/26127/NCGM-established-as-NATO-Department-Head>.

- See NATO, “Bi-Strategic Command Directive (BI-SCD) 40-1,” B-2.

- See NATO, “Chicago Summit Declaration on Afghanistan,” particularly para. 6.

- Amie Ferris-Rotman, “Exiting U.S. General Says Afghan Women’s Rights Are Key,” Reuters, February 9, 2013, available at <www.reuters.com/article/2013/02/09/us-afghanistan-allen-idUSBRE9180AE20130209>.

- See “List of National Action Plans,” PeaceWomen.org, available at <www.peacewomen.org/naps/list-of-naps>.

6. Women, Terrorism, and Counterterrorism: Crafting Effective Security Policies

By Jane Mosbacher Morris

The turn of the 21st century was marked by a heartbreaking and unexpected tragedy: the attacks of September 11, 2001. The barbaric acts of the perpetrators not only changed the lives of thousands, but also solidified terrorism as the preeminent threat to the United States. Many around the world, including American government officials, previously thought the Nation enjoyed the strongest defense in the world. How could a ragtag group have succeeded in planning and executing this plot? The 9/11 Commission, formed to help answer this question, concluded that a contributing factor was that “institutions charged with protecting our borders, civil aviation, and national security did not understand how grave this threat could be, and did not adjust their policies, plans, and practices to deter it.”1 In other words, our national security policies and programs had not sufficiently evolved.

It is within this continual refining of U.S. national security policies that this book arises. No contributor to this work, including myself, advocates for women, peace, and security purely for the sake of empowering women. Instead, we do so to maximize the number of lives saved and improved. This chapter aims to highlight the tangible advantages of considering both women’s roles within terrorist organizations and women’s potential in countering terrorism in the hopes of contributing to more comprehensive security policies and programs.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection agricultural specialists inspect millions of Valentine’s Day flowers annually for pests at Port of Miami’s cargo terminal (U.S. Customs and Border Patrol/James Tourtellotte)

Women and Terrorism

Too often, we presume that women lack the agency to use their brains and brawn to advance malevolent causes. While the number of women and men involved in terrorist organizations pales in comparison to the vast majority of those who strive to maintain peace, ignoring these bad actors, regardless of gender, has dangerous consequences.

Female terrorists, for example, have taken hostages, hijacked airplanes, planted bombs, conducted high-level assassinations, driven explosive-laden vehicles, and committed suicide attacks. A statistical snapshot reveals that women perpetrated an estimated 15 percent of all suicide attacks between 1980 and 2003. In certain organizations, such as the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (Partiya Karkerên Kurdistan) and the Chechen separatists, women were responsible for the majority of suicide attacks.2 Behind the scenes, women have contributed to terrorist organizations by marrying members, cooking and cleaning for them, gathering intelligence, and providing moral support.

Still, some in the security sector assume that because certain violent extremists advocate for restrictive roles for women in society, these organizations would ban women from carrying out terrorist activities. Violent extremists exploit this assumption, however, and instead use women to tactical advantage. Security officers may perceive women as less suspicious and allow them to evade male-dominated checkpoints, for example, particularly in conservative environments. When wearing abayas, the loose caftan-like garments that cover women’s entire bodies, women may be able to hide bulky explosives, presenting a unique security threat for even the most observant officers. Terrorist organizations also strategically leverage women to appeal to the male egos, arguing that if a woman is willing to sacrifice her life or time for the cause, so too should a man.

Some organizations even make special efforts to recruit female participants. Al Qaeda, for instance, produced a glossy magazine, Al-Shamikha, specifically designed for women; the wife of al Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri appealed to mothers “to raise [their] children in the cult of jihad and martyrdom and to instill in them a love for religion and death.”3 Furthermore, mothers pressure their husbands and sons to take up arms for the honor of their families, nations, or religion—and do so more commonly than many outsiders believe.

In other words, it is unrealistic to operate under the premise that all women are inherently more peaceful than all men and therefore unwilling to choose violence for political ends. The relative peacefulness of women versus men is not an unfounded argument, but should not evolve into the mistaken belief that no women are involved in violent extremism. Some women actively lobby against terrorism, some remain silent on the issue, and others actively propagate its use.

Recognizing the unique threats that female violent extremists pose can save lives. Fully acknowledging the various roles that women play within terrorism is just as essential as considering how women can help prevent and resolve conflict.4

South Texas Customs and Border Patrol officer inspects inbound vehicles and checks identification at Juarez Lincoln Bridge port of entry in Laredo, Texas (U.S. Customs and Border Patrol/Donna Burton)

Women and Counterterrorism