Download PDF

Captain Michael S. Silver, USN, is an MH-60 pilot and the prospective Executive Officer of the USS Theodore Roosevelt. Colonel Kellen D. Sick, USAF, is an F-15 Pilot serving on the Joint Staff J7 as a Joint Force Development Strategist. Major Matthew A. Snyder, USA, is a Special Forces Officer serving at Special Operations Command South as Deputy J3. Major Justin E. Farnell, USMC, is a Marine Corps MV-22 Osprey Pilot currently serving on the Joint Staff in the J6 Joint Assessment Division.

In 2002, the Oakland Athletics faced formidable challenges. With a payroll less than a third of the New York Yankees’ $125.9 million and the departure of key players, the Oakland A’s were projected to struggle. Yet they won the American League West division, besting their star-studded 2001 run. Immortalized in the film inspired by Michael Lewis’s book Moneyball, the team’s 2002 season is a case study in leveraging data-driven decisionmaking to challenge and overturn a failing status quo. By prioritizing undervalued metrics, the Oakland A’s constructed a team that tied the Yankees for the most wins in the league for a fraction of the cost. In 2004, the Boston Red Sox adopted this approach to break their 86-year championship drought, demonstrating the competitive edge that data-centric analysis provides in decisionmaking. Just as the 2002 Oakland A’s leveraged data to challenge conventional approaches, modern warfare requires a shift from intuitionbased decisionmaking to artificial intelligence/machine learning (AI/ ML)–enabled decisionmaking. The joint force, like baseball two decades ago, faces an urgent challenge: integrate AI/ML or risk being outmaneuvered by more agile adversaries.

The military and economic dominance of the United States in the post-Soviet era compelled adversaries to shift their strategies away from largescale conventional warfare. Instead, they have increasingly focused on contesting American decisionmaking through cognitive warfare, leveraging psychological, informational, and technological domains to erode strategic advantage. Unlike traditional warfare, cognitive warfare shapes how individuals and organizations perceive reality, evaluate choices, and act on information.1 Russia’s interference in the 2016 U.S. Presidential election and the United Kingdom’s Brexit vote, as well as China’s 2024 use of TikTok to influence Taiwan’s presidential election, demonstrate the profound impact cognitive warfare has had on recent history.2 Moreover, China is aggressively pursuing a future battlefield dominated by autonomy, outpacing adversaries with AI/ ML tools that compress decisionmaking from seconds to milliseconds.3

The proliferation of tools such as China-based DeepSeek AI and U.S.-based ChatGPT has revolutionized private and commercial sectors by accelerating decision cycles.4 These tools can analyze vast and complex data sets in seconds, producing insights that once required entire teams of analysts working over extended periods. For example, JPMorgan Chase uses AI tools to detect fraud and assess credit risk across millions of accounts in near-real time, while the U.S. National Weather Service employs ML models to rapidly process satellite imagery and atmospheric data, generating earlier and more accurate storm forecasts.5 These systems reduce the human cognitive load and enable faster, higher-quality decisions at scale. In the national security domain, where the stakes far exceed those of finance or public safety, a competitive edge in the speed and accuracy of decisionmaking is more critical than ever. In this type of contest, those who can shape narratives, manipulate information, and make superior decisions faster than their competitors achieve victory.6

Despite widespread investment and experimentation in AI/ML, most organizations struggle to increase performance with this technology. Only one-quarter of companies experimenting with AI have generated real value, and less than 5 percent have built AI capabilities at scale.7 Even large companies like Microsoft believe they are transforming, but they are merely using AI to speed up processes rather than fundamentally reshaping operations to optimize performance.8 As evidenced by initiatives detailed on ai.mil, the Department of Defense—now the Department of War (DOW)—has invested billions of dollars into AI/ML capabilities. Still, mere access to this technology has proved insufficient for widescale integration. The struggle is not only technological; it is behavioral. True AI integration requires more than technology; it requires adoption. Understanding why these AI challenges persist is critical to identifying viable solutions and preventing the erosion of strategic advantage. With three-quarters of all organizations yet to see tangible AI benefits, the challenge to adoption lies in amending structures, processes, and people to unlock the full potential of AI/ML.9 DOW must take note and move beyond the status quo, accelerating AI/ML adoption to enhance decisionmaking. At a February 2025 AI Action Summit in Paris, North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) Supreme Allied Commander Transformation, Admiral Pierre Vandier, clearly articulated this imperative: “Artificial intelligence is massively accelerating military decisionmaking, and armed forces that do not keep up risk being outmatched.”10 Using the conflict in Ukraine as an example, he highlighted that the stakes of maintaining the status quo are stark: “If you do not adapt at speed and at scale, you die.”11 Admiral Vandier’s mandate for AI training among officers in Allied Command Transformation underscores the critical insight that adoption, not capability, is the limiting factor for integration.

In this article, we seek to analyze organizational design factors affecting the widescale adoption of AI/ML tools into DOW decisionmaking. We do not address offensive and defensive applications of cognitive warfare; ethical considerations for using AI/ML tools; trust and transparency requirements; or vulnerabilities that using AI/ML tools might present to adversarial actors. These areas represent future research opportunities.

Approach to Analyzing Organizational Design

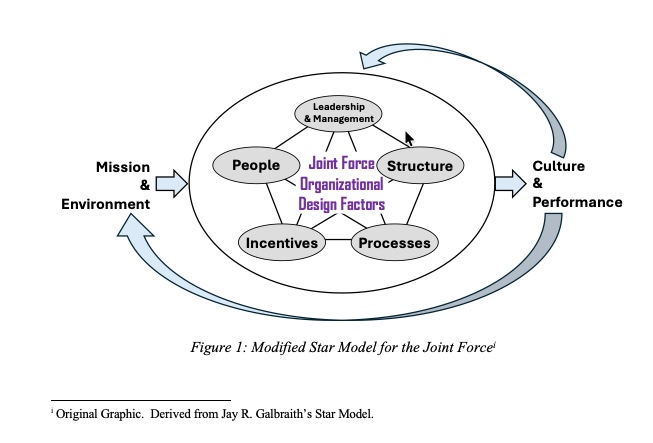

When an organization reaches an inflection point and assesses that the status quo will ultimately lead to its stagnation or decline, it must adapt its organizational design. Jay Galbraith’s Star Model, first introduced in 1977 as a strategic approach to organizational design, provides a useful framework for such adaptation.12 In this article, we modify Galbraith’s Star Model to analyze organizational design factors affecting the widescale adoption of AI/ML tools into DOW decisionmaking. These factors can be applied across tactical, operational, and strategic organizations for warfighting, resourcing, and administrative purposes. The modified Star Model, illustrated in figure 1, includes five organizational design factors: people, structure, processes, incentives, and leadership and management.

The term people refers to the mindset, skill sets, and talents required of the individual workforce to achieve an organization’s goals.13 Structure refers to the location of decisionmaking power. It defines the shape of an organization, reflecting the hierarchy of authority and distribution of power through the lens of what and where decisions are made.14 The term processes refers to the information flows that feed into decisionmaking.15 Incentives are the motivational tools that drive people to exercise processes within a specified structure to achieve organizational objectives.16 Incentives reflect a combination of extrinsic and intrinsic motivators. Leadership and management reflect the role that joint leaders play in establishing strategic direction and priorities for their organizations. They wield considerable influence over the other organizational design factors.17

These five factors operate as interdependent nodes of organizational design, reinforcing or weakening the overall strength of the organization. How these factors interact drives the organization’s performance and cultural outputs. When mission or environmental changes influence one node in the modified Star Model to change, organizations should evolve and adapt to reoptimize the design factors.18 Failure to do so risks organizational impotence or, worse, obsolescence.

Figure 1. Modified Star Model for the Joint Force.

Analyzing Organizational Design Factors

People. The physiology of the human brain as well as the mindset and skill set of people in an organization are critical factors affecting AI/ML adoption. Decisionmaking relies on interconnected cognitive processes shaped by experience and repetition. Over time, familiar workflows become deeply ingrained, leading individuals to rely on default patterns even when new tools become available.19 This is evident in the joint force, where decades of Internet use have conditioned personnel to develop a “search-engine mindset.”20 This habituated approach relies on generating results through indexed, static, keyword-driven interaction. In contrast, AI/ML tools generate dynamic, context-sensitive responses that improve with iteration.

Effective AI/ML adoption necessitates a fundamental shift in human cognitive habits. Just as military planners use multiple iterations to refine initial concepts prior to execution, AI-generated outputs require a similar process to achieve optimal results. However, many users unknowingly limit the effectiveness of AI/ML by treating it as a static query system rather than an interactive tool. Reliance on traditional search-engine workflows has reinforced behaviors that are at odds with AI/ML’s adaptive nature. Users approaching AI/ML with a conventional search-and-response model struggle when the technology requires a different form of interaction. Frustration grows when responses appear incomplete or contain “hallucination” errors that often prompt users to disengage from the technology.21 As Conor Grennan, chief AI architect at New York University’s Stern School of Business, notes, “It’s not that our brain doesn’t know how to use it—it’s more nefarious than that. It’s that our brain thinks it knows how to use it, but it’s wrong.”22 The challenge is not simply learning a new tool; it is retraining deeply ingrained cognitive habits.

Like any weapon system, AI/ML is a purpose-built tool that complements, rather than replaces, existing capabilities. To unlock its full potential, personnel must shift away from treating AI/ML like a search engine to actively shaping AI/ML-generated outputs. For example, a Google query for “develop an operations plan for a joint force mission” yields static templates and archived operations orders (OPORDs). While useful, these resources require hours of manual adjustment to meet dynamic mission requirements. In contrast, a user iterating with a generative AI/ML model can rapidly create a fully customized OPORD tailored to mission-specific inputs. When provided with these inputs, AI/ML can analyze real-time intelligence to identify enemy force positions, vulnerabilities, and likely courses of action (COAs). It can incorporate weather forecasts to assess operational impacts and recommend troop movements, logistics, and contingencies. This iterative process has the potential to significantly accelerate the planning process, reducing planning timelines from days to hours and enabling faster, more informed decisions.

Developing new cognitive habits is only part of the challenge. Effective AI/ ML adoption requires structured training to develop the requisite skills.23 A recent study found that untrained users underperformed when applying AI beyond its intended capabilities, often because they treated it like a search engine. In contrast, trained AI users demonstrated significant gains in both productivity and quality. For individuals normally below the average performance threshold, performance increased 43 percent with effective AI augmentation. Individuals already performing above the average performance threshold still experienced a 17-percent improvement with effective AI augmentation. Additionally, trained AI users completed 12 percent more tasks and worked 25 percent faster than those without AI augmentation.24 These findings highlight the necessity of deliberate AI/ML training to maximize operational effectiveness.

AI/ML training extends beyond technical proficiency in key skill sets such as prompt engineering, iteration and chaining, role-based interaction, and conversational engagement. It must also account for cognitive and behavioral mechanisms that drive adaptation. Training should reinforce positive feedback loops, where improved performance encourages continued use, ultimately leading to the formation of new habits. Achieving this shift requires deliberate implementation efforts to correct the lack of structured reinforcement strategies found in legacy methods. Behavioral change demands a combination of hands-on training, iterative learning, and leadership-driven adoption initiatives. While training programs are essential, adoption also depends on aligning AI/ ML tools with organizational structure.

Structure. Organizational structure determines what decisions are made and where they occur, directly shaping AI/ ML adoption. While mission and environment drive structural design, different structures affect the speed, efficiency, and effectiveness of using AI/ML tools for decisionmaking. Understanding the types of decisions an organization makes reveals how to use AI/ML tools. Identifying where decisions occur reveals where to apply them.

Decisions vary significantly in nature and complexity.25 Administrative tasks like summarizing and disseminating meeting transcripts differ substantially from dynamic battlefield assessments based on emerging targeting information and force posture. Different types of decisions require different AI/ML integration models. Tasks with high variability and unpredictability require a more collaborative approach. In contrast, structured, repeatable decisions allow for greater automation. Common models include full delegation, interaction, and aggregation.26 In full delegation, AI/ ML tools make decisions without human intervention. In interaction, human and AI/ML tools sequentially make decisions such that the output of one decisionmaker provides the input to the other. Project Maven’s augmentation of the targeting cycle is an example of this interaction model. The model can be further subdivided into the “Centaur” and “Cyborg” approaches. The Centaur approach drives human and AI task division based on relative strengths. The Cyborg approach fuses human-AI decisionmaking in real time, leveraging AI for continuous analysis and adaptation while maintaining human oversight for context-driven judgments.27 In aggregation, human- and AI-based decisions are made independently, delegated based on strengths, and then aggregated into a collective decision. In this model, the AI/ML tool becomes a voting member in the decisionmaking process, often weighted based on various criteria. Each model reflects a different balance between human and AI/ML capabilities, tailored to the specific decision type.28

In addition to the type of decision being made, the distribution of decisionmaking power—where decisions occur—determines the optimal placement of AI/ML tools. Mission and environment typically drive this distribution across several structural types. Organizations emphasizing standardization tend toward professional or machine bureaucracies with centralized decisionmaking. Those requiring standardized output across semiautonomous units develop “divisionalized” structures. When project-based adaptive output is essential, organizations benefit from adhocracies—fluid structures with flatter decentralized authority.29 In all cases, AI/ ML tools should be integrated where decisionmaking occurs. Where mission and environment allow structural flexibility, decentralized decisionmaking can enhance AI’s impact by enabling faster and more adaptive responses at lower levels. For example, Ukraine recently embedded Palantir engineers with AI/ML tools into its frontline units to enable rapid decisionmaking on the battlefield.30

AI/ML tools perform best when accessing broad interconnected data sources. Consequently, AI/ML integration is particularly effective in rapidly composable and decomposable crossfunctional teams that synthesize diverse inputs across disciplines. For example, in the convergence between electronic warfare and cyberspace, AI-enhanced threat detection becomes most effective when cybersecurity, signals intelligence, and operations personnel collaborate closely rather than operating in isolated silos.

Conversely, highly centralized structures may limit AI/ML tools to merely advisory roles instead of active components in real-time operations. Formalized hierarchies may also impede the development of the organizational competencies needed for effective adoption.31 Even so, command-structured hierarchies like DOW can still benefit from increasing the vertical or horizontal decentralization of their decisionmaking wherever possible. Organizations face a fundamental tension between maintaining internal coherence for efficiency and adapting to environmental changes. Bureaucracies often struggle with rapid adaptation despite their efficiency at standardization.32 These organizational structures are slow to evolve, often failing to keep pace with changing environments that demand adaptation. Organizations must balance structural adaptation with internal consistency, implementing AI/ML tools according to the type of decision and aligning AI/ML tools to where they most effectively enhance speed, insight, and decision superiority.33

Processes. Adopting AI/ML tools into decisionmaking depends not only on what and where decisions occur, but also on how they are made. Processes are the interconnected activities that shape information flow up, down, and across an organization.34 They facilitate collaboration, coordination, and organizational decisionmaking and affect how AI/ML tools enhance these information flows. Processes apply to both hierarchical and decentralized structures when any level of collaboration between internal boundaries is required to accomplish the mission.35 For the joint force, informal and formal processes must operate seamlessly under conditions of uncertainty, time constraints, and adversary countermeasures.

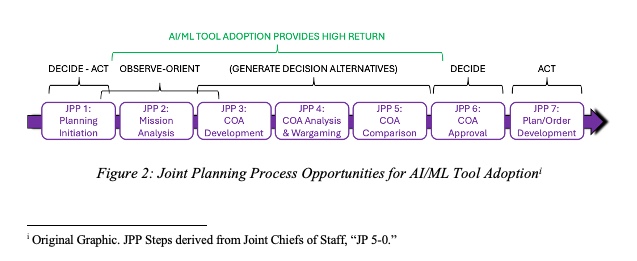

Figure 2. Joint Planning Process Opportunities for AI/ML Tool Adoption

Decisionmaking, while complex, is a cycle of linked information flows.36 John Boyd’s OODA loop—observe, orient, decide, and act—provides a helpful simplification. Born out of the needs of aerial combat, the OODA loop asserts cycling faster than an opponent through this loop would produce advantages in combat. Conceptually, Boyd’s ideas hold weight for using AI/ML tools in cognitive warfare. In the observe and orient steps, actors gather and perceive information and build mental models of the environment, threats, opportunities, and risks. An implied step is generating decision alternatives and comparing those alternatives before selecting one (the decide step) and then executing it (the act step).37 Given this simplified framework, AI/ML tools are well suited for adoption in observe-orient processes and in generating and comparing decision alternatives. Using the Joint Planning Process (JPP) as a representative military decisionmaking process highlights these opportunities (see figure 2).

In its most distilled form, the JPP is a series of information flows executed across several functions to produce products and staff actions leading to commander decisions. Doctrinally, the JPP facilitates planning interactions among the commander, planning staff, and lower echelons.38 This framework is a recursive, assessment-informed process in which issues that planners discover in later steps drive adjustments to earlier steps, and commanders have the flexibility to truncate, modify, or concurrently execute its seven steps depending on the situation or available time.39

To initiate planning, the commander must have a means by which to recognize, monitor, and react to changing trends in the environment. If the commander centralizes this function, he or she risks missing salient trends. However, disaggregating this function increases the requirement for processes. Previously, the larger the organization and the more disaggregated the processes, the more manpower was required to make decisions, resulting in slower decision cycles. AI/ML tools can accelerate decisionmaking processes by providing faster pattern recognition and sensing insights from a wider data set, enabling proactive rather than reactive planning.40 For example, AI/ML tools can rapidly analyze raw intelligence data and highlight changes that exceed human-defined thresholds, reducing the need for manual data analysis and allowing humans to focus on critical and creative thinking.41

Once planning is initiated, AI/ML accelerates data-intensive mission analysis by fusing intelligence sources and force readiness reporting into a unified operational picture. This is critical for framing the problem and guiding COA development. Previously, these inputs were processed and visualized separately and with direct staff intervention, making it difficult for commanders to develop a comprehensive picture of the operating environment and the military problems they must solve. Instead, planners can use AI/ML tools to process terabytes of data, rapidly displaying information according to human-defined parameters. They can also use AI/ML tools to provide multiple visualization options for decisionmakers to consider.42

After this step, planners must develop decision alternatives for commander approval. In the JPP, this involves COA development, COA analysis and wargaming, and COA comparison. At this stage, planning shifts from critical to creative thinking. Still, planners currently generate solutions using manual methods of iteration, limited by the expertise and experience of their teams, and present the results using antiquated visualization tools like PowerPoint. AI/ML tools allow aggregation of large amounts of data across disparate functions and sources to generate multiple COAs faster and from a wider range of perspectives, reducing reliance on individual expertise and manual iteration.

Planners can use AI/ML tools to assume a unique persona when assessing potential adversary, neutral, and friendly reactions. With proper inputs, AI/ML tools can also role-play the “red team,” speeding up the iterative play of war games. These tools facilitate the background analysis needed to identify a COA’s strengths, weaknesses, and risks. Planners can also use AI/ML tools to assess multiple COAs based on the commander’s priorities, constraints, and restraints.43 These opportunities for AI/ ML tool integration allow planners to compare, refine, and evaluate COAs, deepening the analysis supporting their COA recommendations to the commander. While AI-generated COAs are powerful, planners must resist overreliance on them and ensure that machine-generated options are filtered through human judgment, operational context, and commander’s intent. As previously noted, AI/ ML tools should augment, not replace, the iterative cognitive processes that underpin military decisionmaking.

Once the commander selects a COA, planners can use AI/ML tools to draft and disseminate the plan and orders on behalf of the commander. AI/ML tools can craft outputs from a wide range of inputs based on specified formats. Currently, the process of generating plans and orders involves the manually intensive task of transcribing the analysis and decisions made during planning to generate products like OPORDs.

Integrating AI/ML tools into the JPP illustrates just one of many opportunities where AI/ML-enabled processes enhance the effectiveness of information flow at machine speeds. AI/ML tools enhance a decisionmaker’s ability to observe and orient and then develop a wide range of decision alternatives for refinement, comparison, and evaluation before selecting the optimal choice. For other processes, the adoption challenge lies in recognizing which information flows AI/ML tools are primed to support and then optimizing their use. Predictable and repeatable processes such as intelligence synthesis and aggregation, as well as force readiness assessment, lend themselves to more automated decisions using AI/ML tools. Ambiguous, iterative, or creative processes like mission analysis, adversary modeling, and COA development lend themselves to interaction models like the Centaur or Cyborg approaches discussed earlier. Processes related to the evaluation of decision alternatives, such as COA comparison, lend themselves to the aggregated use of AI/ML tools.

Incentives. Incentives drive behavioral change, aligning individual and organizational goals to ensure mission effectiveness. If DOW is to pursue the broadscale adoption of AI/ML tools into decisionmaking, its leaders must carefully evaluate the impact of incentives and disincentives on organizational performance, particularly regarding the acceptance of change. The status quo acts as an adversary to change, manifesting in deeply rooted organizational habits that create resistance to the changes needed for progress.44

Resistance can be individual or organizational. Individual resistance is either malicious or nonmalicious. Malicious resistors actively create obstacles to preserve self-value, often driven by fears of emerging technology displacing their position in the organization. Nonmalicious resistors, by contrast, may simply lack understanding of the change, making them reluctant to venture beyond familiar practices.45

Organizational resistance may manifest in several ways. First, social and cultural resistance may stem from generational preferences for traditional methods. This could be due to a lack of AI/ML tool literacy or misunderstandings about the technology’s potential application. This resistance is more pronounced in hierarchical structures like DOW, where time-in-service promotion systems concentrate decisionmaking authority within a single generation. Second, ethical and moral criticism creates organizational resistance that centers on concerns about trustworthiness, authenticity, and potential plagiarism of using AI-generated content. “AI shaming”—the criticism of using AI/ML tools based on ethical concerns, perceptions of laziness, or trust issues—can manifest both horizontally and vertically within an organization.46 Third, perceptions of the impact that AI/ ML tools have on individual skill requirements, job security, and authority may contribute to this resistance.47

Within each category of resistance, there is likely a champion of the status quo whose behavior joint leaders must influence by providing appropriate incentives for change. For example, this could be the senior warrant officer preferring traditional tools, a noncommissioned officer concerned about security implications, a staff officer fearing job obsolescence, or a general officer who does not trust AI-produced products, demanding intensive staff labor no matter the impact on efficiency.

Overcoming this resistance requires a balanced approach to incentives. While structural and process changes can address tangible obstacles, overcoming entrenched habits requires careful attention to incentives. Incentives can be extrinsic (for example, compensation, promotions, and recognition) or intrinsic (job satisfaction, challenging work, and personal fulfillment).48 While extrinsic incentives may help jump-start the early adoption of AI/ML tools, intrinsic incentives ultimately shape the organizational culture needed for longterm transformation.

Intrinsic incentives offer several opportunities for individual and organizational growth and development. For instance, AI/ML tools may enhance individual and group research efficiency across various disciplines, subsequently streamlining product-generation timelines. Additionally, human-machine collaboration allows organizations to leverage the creative and computational strengths of both, facilitating rapid data analysis and creative problem-solving. Finally, mitigating self-biases through education and training develops a growth-minded culture within the organization. This type of culture unlocks additional innovation, normalizes change, and increases intrinsic incentives that drive individuals and organizations toward aligned goals.

The combination of extrinsic and intrinsic incentives should be tailored to the type of resistance the organization experiences. However, organizations may be constrained by what incentive levers they can affect to motivate desirable behaviors. This leaves joint leaders with the challenge of identifying the right influence tools to promote the growth and transformation within their organizations to achieve widescale adoption of AI/ML tools.

Leadership and Management. An organization’s leadership and management greatly influence organizational design factors affecting the adoption of AI/ML tools into decisionmaking. However, joint leaders must first address their own AI/ML literacy before they can effectively adapt the other organizational design factors for AI/ML tool adoption. Without understanding AI/ML capabilities and limitations, leaders risk either over-relying on these tools or under-utilizing them because of skepticism.49 For example, using AI/ML-enabled decision aids can enhance battlefield effectiveness, but only if commanders know how to interpret their suggestions and trust their outputs.

Beyond developing personal AI/ML literacy, joint leaders must articulate a compelling vision for change and a clear path to pursue it.50 This communication is particularly important for addressing nonmalicious resistance, which often stems from a lack of understanding rather than active opposition. Leaders must recognize that resistance to AI/ML adoption will manifest differently across their organizations and tailor incentives to overcome the specific type of resistance they encounter. Leaders who create a growth-minded organizational culture create a powerful complement to more direct incentives. Such cultures become self-reinforcing as improved results demonstrate the value of AI/ML tools, normalizing their adoption.51

Joint leaders must systematically assess how organizational design factors affect AI/ML adoption in their units. For people, this means driving the training initiatives to shift mindsets from “search-engine thinking” to understanding the interactive use of AI/ML tools. It also means driving the training initiatives to develop new skill sets like prompt engineering and iteration techniques to optimize human-AI collaboration. Where mission and environment allow flexibility, joint leaders should consider structural choices that better enable AI/ML adoption to accomplish their mission through faster and wider-informed decisionmaking. This generally involves pushing decisionmaking down and to the edges of an organization, flattening the structure to facilitate cross-functional collaboration, iteration, and parallel use of AI/ ML tools. To do this, joint leaders must assess what decisions are made in an organization and where decisions are made, restructuring to optimize the use of AI/ML tools. When necessary, command relationships drive hierarchical structure, and joint leaders should still identify vertical and horizontal decentralization opportunities to maximize AI/ML tool effectiveness. In processes, joint leaders must guide the adoption of AI/ML tools into the information flows that feed their decision cycles, identifying which flows benefit from fully automated or hybrid approaches. Ultimately, joint leaders must recognize that the adoption of AI/ML tools requires synchronized adaptation across all organizational design factors.

Leadership and management play an outsized role in shaping organizational design factors. The combination of these factors drives an organization’s performance and culture. Joint leaders who fail to proactively adapt their organizations for AI/ML adoption risk leaving the joint force anchored to legacy decisionmaking models that compromise strategic advantage.

Conclusion

In modern warfare, decision dominance is highly correlated with victory. AI/ML tools are reshaping the battlespace by enhancing the speed and precision of decisions. For DOW, failure to meaningfully adopt these tools carries severe consequences, including slower operational tempo, increased cognitive overload, a higher probability of intelligence blind spots, and reduced force readiness.52

This analysis reveals that widescale integration of AI/ML tools hinges not only on technological capability and access but also on organizational design factors affecting the adoption of AI/ML tools. To break from a status quo deeply rooted in outdated habits of human cognition, institutional resistance, and legacy decisionmaking processes, DOW must adapt its people, structure, processes, incentives, and leadership and management.

The imperative is clear. DOW must accelerate the adoption of AI/ML tools into its decisionmaking. Failure to do so risks the joint force being outpaced by adversaries who weaponize AI/ ML tools to operate more effectively. As these tools move further left in the decision continuum, they will increasingly shape how problems are framed, options generated, and actions selected. Human judgment still plays a role, and must evolve in parallel, but it must not become a brake on progress. In short, failure to adopt AI/ML at speed invites obsolescence, an untenable option for U.S. national security.53 JFQ

Notes

1 Marie Morelle et al., “Towards a Definition of Cognitive Warfare,” HAL Open Science, December 7, 2023, Conference on Artificial Intelligence for Defense, DGA Maîtrise de l’Information, November 2023, Rennes, France, https://hal.science/hal04328461v1/document.

2 Patrick Tucker, “How China Used TikTok, AI, and Big Data to Target Taiwan’s Elections,” Defense One, April 8, 2024,

https://www.defenseone.com/technology/2024/04/how-china-usedtiktok-ai-and-big-data-target-taiwanselections/395569/.

3 Kevin Pollpeter and Amanda Kerrigan, The PLA and Intelligent Warfare: A Preliminary Analysis, with Andrew Ilachinski (Arlington, VA: CNA, October 2021), https://www.cna.org/reports/2021/10/The-PLA-and-Intelligent-Warfare-A-Preliminary-Analysis.pdf.

4 Sam Ransbotham et al., “Achieving Individual—and Organizational—Value With AI,” MIT Sloan Management Review, October 31, 2022,

https://sloanreview.mit.edu/projects/achieving-individual-and-organizational-value-with-ai/.

5 “Payments Unbound,” n.d., accessed August 5, 2025, https://www.jpmorgan.com/payments/payments-unbound/volume-3/smart-money; Theo Stein, “NOAA Research Develops an AI-Powered Sibling to Its Flagship Weather Model,” NOAA Research, July 22, 2025,

https://research.noaa.gov/noaa-research-develops-an-ai-powered-sibling-to-its-flagship-weather-model/.

6 Kathy Cao et al., “Countering Cognitive Warfare: Awareness and Resilience,” NATO Review, May 20, 2021,

https://web.archive.org/web/20250402203501/https://www.nato.int/docu/review/articles/2021/05/20/countering-cognitive-warfare-awareness-and-resilience/index.html.

7 Nicolas de Bellefonds et al., Where’s the Value in AI? (Boston: Boston Consulting Group, October 2024),

https://www.bcg.com/publications/2024/wheres-value-in-ai.

8 Connor Grennan, “Connon Grennan on Moving Beyond the ‘Search Engine Mindset,’” interview by Molly Wood, Microsoft WorkLab, January 7, 2025, podcast audio, 26:50, https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/worklab/podcast/conor-grennan-on-moving-beyondthe-search-engine-mindset.

9 Bellefonds et al., Where’s the Value in AI?

10 Rudy Ruitenberg, “Survival of the Quickest: Military Leaders Aim to Unleash, Control AI,” Defense News, February 13, 2025,

https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2025/02/13/survival-of-the-quickestmilitary-leaders-aim-to-unleash-control-ai/.

11 Ruitenberg, “Survival of the Quickest.”

12 Jay R. Galbraith, “Organization Design Challenges Resulting from Big Data,” Journal of Organization Design 3, no. 1 (2014), 2–13,

http://dx.doi.org/10.7146/jod.8856.

13 Jay R. Galbraith, Designing Organizations: Strategy, Structure, and Process at the Business Unit and Enterprise Levels, 3rd ed. (Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass, 2014), 52–3.

14 Galbraith, Designing Organizations, 22–3.

15 Galbraith, Designing Organizations, 37–8.

16 Galbraith, Designing Organizations, 44.

17 Galbraith, Designing Organizations, 22–3.

18 Jay R. Galbraith, “The Star Model,” n.d., 4–5, https://jaygalbraith.com/services/star-model/.

19 Casey Henley, Foundations of Neuroscience (East Lansing: Michigan State University Libraries, 2021), 349–53,

https://openbooks.lib.msu.edu/neuroscience/.

20 Conor Grennan uses the term searchengine mindset in his course. See “Generative AI for Professionals: A Strategic Framework to Give You an Edge,” AI Mindset, https://www.ai-mindset.ai/gen-ai-for-professionals. See also Connor Grennan, “Connon Grennan on Moving Beyond the ‘Search Engine Mindset,’” interview by Molly Wood.

21 Fabrizio Dell’Acqua et al., “Navigating the Jagged Technological Frontier: Field Experimental Evidence of the Effects of AI on Knowledge Worker Productivity and Quality,” SSRN Scholarly Paper no. 4573321 (Social Science Research Network, September 15, 2023),

https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4573321.

22 “Generative AI for Professionals.”

23 “AI Rapid Capabilities Cell,” DOD Chief Digital and Artificial Intelligence Office, accessed February 20, 2025,

https://www.ai.mil/Initiatives/AI-Rapid-Capabilities-Cell/.

24 Non-AI users relied solely on conventional, human-driven workflows, resulting in lower productivity. AI with nontrained users achieved productivity improvements but were prone to increased errors due to reliance on AI for unsuitable tasks. AI with trained users leveraged iterative prompting to refine outputs, optimizing task performance by balancing AI capabilities and human intuition. See Dell’Acqua et al., “Navigating the Jagged Technological Frontier.”

25 Decision complexity varies based on the breadth of information considered, output interpretation requirements, option generation, time constraints, and repeatability needs. See Yash Raj Shrestha et al., “Organizational Decision-Making Structures in the Age of Artificial Intelligence,” California Management Review 61, no. 4 (2019), 1, https://doi.org/10.1177/0008125619862257.

26 Shrestha et al., “Organizational DecisionMaking Structures in the Age of Artificial Intelligence,” 5, 9–10.

27 Dell’Acqua et al., “Navigating the Jagged Technological Frontier.”

28 Shrestha et al., “Organizational DecisionMaking Structures in the Age of Artificial Intelligence,” 12.

29 Henry Mintzberg, “Organization Design: Fashion or Fit?” Harvard Business Review, January 1, 1981,

https://hbr.org/1981/01/organization-design-fashion-or-fit.

30 Richard Farnell and Kira Coffey, “AI’s New Frontier in War Planning: How AI Agents Can Revolutionize Military Decision-Making,” Harvard Kennedy School Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, October 11, 2024,

https://www.belfercenter.org/research-analysis/ais-new-frontier-war-planning-how-ai-agents-can-revolutionize-military-decision.

31 Mathieu Bérubé et al., “Barriers to the Implementation of AI in Organizations: Findings from a Delphi Study,” paper presented at Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 2021, https://doi.org/10.24251/HICSS.2021.805.

32 Mintzberg, “Organization Design.”

33 Mintzberg, “Organization Design.”

34 Amy Kates and Jay R. Galbraith, Designing Your Organization: Using the STAR Model to Solve 5 Critical Design Challenges (Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass, 2007), 17, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/nationaldefense-ebooks/detail.action?docID=315230.

35 Kates and Galbraith, Designing Your Organization, 37.

36 Kates and Galbraith, Designing Your Organization, 4.

37 “John Boyd and the OODA Loop,” Psych Safety, n.d., accessed February 20, 2025, https://psychsafety.com/john-boyd-and-the-ooda-loop/.

38 Joint Publication 5-0, Joint Planning (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, July 1, 2024), III–10.

39 The seven steps of the JPP are planning initiation; mission analysis; course of action (COA) development; COA analysis and wargaming; COA comparison; COA approval; and plan or order development.

40 Thomas W. Spahr, “Raven Sentry: Employing AI for Indications and Warnings in Afghanistan,” Parameters 54, no. 2 (2024),

https://press.armywarcollege.edu/parameters/vol54/iss2/9/.

41 Justin Doubleday, “Pentagon Shifting Project Maven, Marquee Artificial Intelligence Initiative, to NGA,” April 26, 2022,

https://federalnewsnetwork.com/intelligence-community/2022/04/pentagon-shifting-project-maven-marquee-artificial-intelligence-initiative-to-nga/.

42 International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights, Artificial Intelligence and Related Technologies In Military Decision-Making on the Use of Force in Armed Conflicts (Geneva: ICRC, March 2024),

https://www.icrc.org/en/publication/expert-consultation-report-artificial-intelligence-and-related-technologies-military.

43 Farnell and Coffey, “AI’s New Frontier in War Planning.”

44 Tom Galvin, Leading Change in Military Organizations: Primer for Senior Leaders (Carlisle, PA: U.S. Army War College, 2018), 97,

https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/AD1124769.

45 Galvin, Leading Change in Military Organizations, 97.

46 Louie Giray, “AI Shaming: The Silent Stigma among Academic Writers and Researchers,” Annals of Biomedical Engineering 52, no. 9 (2024), 2319, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-024-03582-1.

47 Giray, “AI Shaming,” 2320–21.

48 Galbraith, Designing Organizations, 44.

49 Bérubé et al., “Barriers to the Implementation of AI in Organizations.”

50 Galvin, Leading Change in Military Organizations, 98.

51 Edgar H. Schein, Organizational Culture and Leadership, 4th ed. (Hoboken, NJ: JosseyBass, 2010).

52 David Vergun, “AI to Give U.S. Battlefield Advantages, General Says,” U.S. Department of Defense, September 24, 2019,

https://www.defense.gov/News/NewsStories/Article/Article/1969575/ai-to-giveus-battlefield-advantages-general-says/.

53 During the preparation of this work, the research team used ChatGPT 4.0, Claude, and Perplexity to assist with outlining, structure, and proofreading. Subsequently, the research team thoroughly reviewed and edited the content as necessary.