Colonel James C. McArthur, USMC, is Chief of the Joint Doctrine Division on the Joint Staff. Ms. Cara Allison Marshall is a Director at the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) for Policy. Mr. Dale Erickson is a Fellow in the Center for Complex Operations, Institute for National Strategic Studies, at the National Defense University. Colonel E. Paul Flowers, USA, is a Director at OSD Personnel and Readiness. Lieutenant Colonel Michael E. Franco, USA, is a Staff Officer at OSD Policy. Lieutenant Colonel George H. Hock, USAF, is a Branch Chief at Air Force Special Operations Command. Colonel George E. Katsos, USAR, is a Strategist on the Joint Staff. Lieutenant Colonel Luther L. King, USAF, is a Division Chief at U.S. Special Operations Command. Commander William E. Kirby, USN, is a Staff Officer at U.S. Pacific Command. Mr. William M. Mantiply is a Branch Chief on the Joint Staff. Lieutenant Colonel Michael E. McWilliams, USMC, is a Deputy Division Chief on the Joint Staff. Mr. A. Christopher Munn is a Unit Chief at OSD Intelligence. Lieutenant Commander Jeffrey K. Padilla, USCG, is a Planner at Coast Guard Headquarters. Mr. Elmer L. Roman is a Director at OSD Acquisitions, Technology, and Logistics. Mr. Raymond E. Vanzwienen is a Planner at U.S. Transportation Command. Commander Jeffrey P. Wissel, USN, is a Staff Officer at U.S. Southern Command.

This article completes a trilogy on interorganizational cooperation—with a focus on the joint force perspective. The first article discussed civilian perspectives from across the U.S. Government and their challenges in working with the military and highlighted the potential benefits of enhancing unity of effort throughout the government.1 The second article presented humanitarian organization perspectives on interfacing with the military and served to illuminate the potential value of increased candor and cooperation as a means to develop mutually beneficial relationships.2 In this final installment, the discussion focuses on how the joint force might assess and mitigate the issues raised by the first two articles through application of the joint doctrine development process.3 This article also explores how joint doctrine can assist in developing and sustaining the relationships that are essential for building effective and cooperative processes in the operational environment. Although the authors accept that cultures and missions vary widely among different types of organizations, we suggest there is a mutual benefit to be achieved from deep understanding of not only one’s own organization but also each other’s perspectives, methods, and structures.

Relief supplies from USAID unloaded off Marine Corps UH-1Y Venom from Joint Task Force 505 in remote area of Nepal during Operation Sahayogi Haat (U.S. Marine Corps/Hernan Vidana)

Background

In the first two articles, we merged the terms for civilian-led departments, agencies, organizations, and groups into one single term: organizations. The sole purpose for consolidating these terms was to provide a simple, consistent expression to capture the entirety of nonmilitary personnel. The trilogy’s title also prompted discussion among the authors regarding the nuances between coordination, collaboration, and cooperation.4 Coordination is a term commonly used within the Department of Defense (DOD) and is often misunderstood as synonymous with both collaboration, which is akin to an interagency approach to command and control, and cooperation. Within the larger government, coordination may imply the presence of a hierarchical relationship where the higher authority directs coordination among organic and external organizations. This prospect often causes concerns for civilian organizations, particularly when the military is involved. Therefore, especially within diplomatic circles, the term collaboration is frequently used instead. Collaboration is more acceptable within the government since it implies the existence of parallel organizational processes working toward a common solution. However, to some humanitarian organizations, when this term is used in the context of working with the U.S. or other military organizations, it creates a risk of blurring perceptions of impartiality, which humanitarian organizations consider essential for their operations. For those organizations, the term most commonly used is cooperation. Since the U.S. military can benefit from communicating and information sharing with any civilian organization, the authors chose to use the term interorganizational cooperation to highlight the importance of developing and maintaining relationships with all civilian organizations.

The term policy also needs clarification in the context of civilian policy or military strategic documents that influence joint doctrine. Unless otherwise stated, use of the term policy here refers to civilian policy. Lastly, we address the difference between the political and military use of the term doctrine. Civilians in the political sphere often use the term doctrine to describe a political policy (for example, the Truman Doctrine, Monroe Doctrine, the responsibility to protect doctrine). This distinction may cause confusion when communicating with the joint force about joint doctrine, which the military uses to describe the documentation and maintenance of best practices used for guiding commanders and their staffs for the employment of military forces. Policy and joint doctrine each play unique roles in providing the objectives and frameworks under which organizations conduct operations. Accordingly, comprehension of the appropriate roles of policy and joint doctrine is essential to understanding how and why different organizations adapt to real world conditions.

Policy and Joint Doctrine

Advancement of interorganizational cooperation is directly impacted by the relationship between joint force development and policy development. Since the joint force is admittedly not a one-size-fits-all solution to U.S. foreign policy issues, the joint force must develop policies and new joint doctrine to shape and evolve today’s warfighters to embrace interorganizational cooperation as a core competency of the future force. As such, the Joint Staff J7 Joint Force Development Directorate performs five functions: joint doctrine, joint education, joint training, joint lessons learned, and joint concept development.5 This article focuses primarily on the role of joint doctrine and its relationship with other joint force functions.

The fundamental purpose of joint doctrine is to formally capture how the joint force carries out certain functions, which in turn prepare successive generations of warfighters to carry out and improve on best practices employed in different operational environments. Policy acknowledges joint doctrine but also provides an authoritative source for required actions—goals or objectives—or specific prohibitions, which guides the joint force to carry out operational functions in a legal and ethical manner, ultimately driving joint doctrine development. Policy and joint doctrine work together constructively to inform and assist DOD with joint force development and risk management assessments. Despite their separate and unique purposes, policy and joint doctrine offer critical synergies during the development of standardization (for example, terminology, command relationships) and commonality across DOD.

Lack of agreement normally occurs during the development of joint doctrine, as various subject matter experts can often be unfamiliar with the joint doctrine and policy development process and the different role that each contributor plays. As joint doctrine plays a prominent role in influencing joint force development, many incorrectly assume that since civilian policy also influences joint force development, that policy is synonymous with joint doctrine. The fact is they are dissimilar; policy can provide an impetus for new practices, while joint doctrine provides a historically influenced and vetted repository of joint force best practices that serves as a starting point for the conduct of military operations. There is a great potential for disagreement between civilian organizations and DOD during development of crisis response options in situations where the joint force perceives that the desired investment of resources and preferred outcomes on the part of policymakers are at odds with the military courses of action. In these instances, an understanding of the relevant joint doctrine provides policymakers with a common foundation from which to discuss appropriate concepts and levels of risk.

On the other hand, institutionally speaking, DOD planning in the absence of established joint doctrine can be challenging. For example, in 2011, the U.S. military’s involvement in preventing a potential mass atrocity in Libya underscored the lack of joint doctrine specific to the unique challenge. As a result, the joint force defaulted to the closest concepts available even though they were inadequate to the particular situation. Despite prior recognition of the joint doctrine gap, the adaptation of mass atrocity doctrine into joint doctrine was developed subsequent to and as a direct result of actual policy developments.6 While joint doctrine is clearly influenced by policy, it also requires frequent updates to remain relevant. Due to its sheer size, no other U.S. Government organization operates with the same scope or scale as DOD; joint doctrine provides a standing framework for DOD organizations to function and from which to adapt over time. An understanding of the interplay in the roles of policy and joint doctrine is critical to ensuring effective adaptation within the joint force.

New challenges in the future operating environment will require increased interorganizational cooperation to better align joint force capabilities with national policy decisions. The ability to integrate joint doctrine with civilian activities, or to at least have a fundamental understanding of civilian policy and procedure development, will help reduce planning, execution, and acquisition timelines when assessing courses of action and implementing them. Policy can arguably be viewed as easier, faster, and more responsive to short-term requirements, yet policy—just like joint doctrine—is not infallible since it too can be forced to adapt to real-world conditions. As the joint force develops its courses of action from a doctrinal foundation, ad hoc policy creation in support of political course corrections may create unintended consequences in interorganizational cooperation and unity of effort. This fact underscores the need for both political and military establishments to work together to align both policy and joint doctrine for efficient achievement of the desired strategic endstate.

Doctrine-Based and Rules-Based Workforces

Interoperability between doctrine and rules-based workforces offers a means to produce military and civilian leaders who understand interorganizational cooperation and how to coordinate and build synergy. The authors presume for this discussion that most organizations are values-based—that is, they are made up of morals, attributes, or principles that guide mission selection, strategic planning, objective identification, and decisionmaking. These values-based organizations conduct activities guided by their organizational policies as implemented by their strategic documents, mandates, and administrative norms. Strategic documents generally guide both civilian and military organizational objectives, while policy documents determine the operational rules that impact routine business. For civilian organizations, these rules can take the form of administrative instructions, organizational mandates, policies, directives, or other tools as captured in figure 1. These civilian organizations provide certain capabilities for foreign or domestic assistance, and each organization provides its own workforce to contribute to the whole-of-government effort—in this case, through rules-based workforces.

|

Figure 1. Examples of Policies That Drive Workforce Execution

|

|

Internal to U.S. Government

|

Overarching Policies

National Security Strategy

Presidential Directives

|

|

Civilian Workforce

- Organizational Strategic Plans, Priorities, and Cross-Agency Priority Goals

- Quadrennial Reviews

- Embassy Mission Resource Plans

- Country Development Strategies and Plans

- National Strategy for Homeland Security

- National Response Framework

|

Military Workforce

- Unified Command Plan

- National Defense Strategy

- Quadrennial Defense Review

- Strategic Planning Guidance

- National Military Strategy

- Joint Strategic Capabilities Plan

- Directives, Instructions, and Memorandums

|

|

External

to U.S. Government

|

Overarching Policies

- International Conventions, Protocols, and Statutes

- Charters, Resolutions, and Declarations

- Treaties

- Institutional Policies and Strategic Plans

- Frameworks and Guideline Documents

- Organizational Mandates

- Foreign Government Defense and Diplomatic Strategies and Plans

|

In contrast, while civilian policies can outline workforce approaches to achieve objectives (figure 1), joint doctrine serves a greater role for the military in defining operational forces. Within the U.S. Government, the DOD operational workforce known as a “joint force” deploys under the authority of a combatant commander, whose operational forces are primarily organized as a joint force or can also be a single-Service force to meet specific operational objectives. The remaining DOD organizations exist to support the joint force, either via logistics, management, and support functions or by the “organize, train, and equip” functions of the Services. Depending on mission requirements and the operational environment, a joint force may contain a range of functional capabilities provided by multiple Services. The joint force streamlines decisionmaking by establishing a hierarchical command and control structure within the joint doctrine framework that also allows sufficient flexibility to adapt to new challenges; thus, the joint force exists as a doctrine-based workforce.

Despite the advantages of organization and efficiency, a doctrine-based workforce such as the joint force has drawbacks. Lengthy planning cycles, a bureaucratic vetting and staffing process, and a strong institutional cultural bias toward action may be reasons that civilian leaders employ non-DOD organizations with security-like capabilities but without doctrine-based constraints. However, the joint doctrine development process is consciously designed to be adaptable. It provides the means to develop and promulgate new joint doctrine within 1 year, and in the case of existing joint doctrine, urgent change recommendations can be incorporated and promulgated in a significantly shorter time frame.

Helicopter assigned to USNS Matthew Perry (T-AKE-9) transports personnel to medical exchange during Association of Southeast Asian Nations Humanitarian Assistance/Disaster Relief and Military Medicine Exercise, hosted by Brunei, June 2013 (U.S. Navy/Paul Seeber)

A significant challenge arises when the military seeks to incorporate civilian viewpoints into its joint doctrine development process. Bringing together separate frameworks requires an understanding that, in contrast to military organizations, civilian organizations may not formally publish comparable doctrine that is reinforced by best practices as compared to the joint force; however, civilian organizations are nonetheless governed by their own internal rules even if those rules are not called “doctrine.” These rules, however, are not always intrinsically grounded in proven organizational best practices and could lead to varying interpretations across organizational components. They can be affected by personality-driven planning and cross-organizational conflict within a multi-organization environment. The cultural contrast between a doctrine-based and rules-based workforce is a principal driver of the miscommunication, divergent planning, and political discord that can plague any multi-organization endeavor. From a joint force perspective, understanding the organizational rubrics and cultures that guide civilian organization activities is a critical step toward the establishment of more effective cooperation across organizational boundaries. This remains a primary challenge for the military as it seeks to incorporate civilian perspectives into joint doctrine development.

The basic notion of a workforce implies a level of standardization and commonality that provides an opportunity to establish effective cooperation across organizational boundaries. While acknowledging that doctrine-based and rules-based workforces have different constraints, there is often a core set of standards and values that govern both workforces. For DOD, identifying this common set of core values and standards and integrating a more thorough understanding of the systems, processes, and cultural dynamics of relevant civilian organizations into joint doctrine will assist with understanding and developing a joint force plan to construct an overall government approach to a military operation. Costs, complexity, and the need to support globally integrated operations combine to necessitate the incorporation of civilian perspectives into joint force planning and execution—and, by extension, into joint doctrine. While many, if not most DOD and civilian organizational functions and capabilities may not be interchangeable, they may be interoperable and in some cases interdependent. Incorporating civilian perspectives into joint doctrine offers potential benefits of optimizing resources and minimizing redundancies without compromising efficiency or operational success.

Joint Doctrine Influence

Joint doctrine that recognizes the intrinsic value of civilian perspectives can ultimately drive interorganizational cooperation by striking a balance between military and civilian influences concerning military capabilities (for example, current force structures, equipment, and resources), capability development, and resource investment. Led by the Joint Staff J7, the joint force development process integrates documented military Service capabilities to execute assigned missions. For purposes of this article, the spectrum of joint force development is grouped into past, present, and future phases, which respectively provide historical lessons and experiences, current operating frameworks, and considerations for adaptation (see figure 2). While civilian governmental policies inform military policy and strategy development, operational planning, military operations, and joint doctrine development, they are also informed by military advice provided by the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff that is itself grounded in joint doctrine.

Joint doctrine incorporates principles of joint operations, operational art, and elements of operational design and standardizes terminology, relationships, and responsibilities among the Armed Forces to facilitate solving complex problems.7 In addition, joint doctrine provides information to civilian leaders responsible for strategy development who may be unfamiliar with military core competencies, capabilities, and limitations. Joint doctrine links the National Military Strategy to the National Security Strategy and provides a common framework for military planning. It forms the basis of the ends-ways-means construct to describe what must be accomplished, how it will be accomplished, and with what capabilities.

For example, a need for an overarching policy and more organized strategy for improving the security sectors of partner nations led to the establishment of Presidential Policy Directive 23 (PPD-23), Security Sector Assistance, which requires a collaborative approach both within the U.S. Government and between civilian and other military organizations and is aimed at strengthening the ability of the United States to help allies build their own security capacity. PPD-23 implies unity of effort across the government through participation in interagency strategic planning, assessment, program design, and implementation of security sector assistance. The joint doctrine–specific outcome of the PPD-23 process was the requirement for a Joint Publication (JP) on security cooperation, JP 3-20.8 Lastly, joint doctrine provides interagency, intergovernmental, and treaty-based organizations with an opportunity to better understand the roles, capabilities, and operating procedures used by the Armed Forces.9

The first phase in the spectrum of joint force development is the past phase that captures completed or ongoing military operations observations or lessons learned for incorporation into joint doctrine. The lessons learned component entails observation, analysis, and translation of lessons learned into actions that improve the joint force. For example, in 2012 the Director of Joint Force Development directed a more aggressive path for counterinsurgency joint doctrine development:

to guarantee we capture what we’ve learned about the conduct of counterinsurgency over the last decade and to harmonize joint and service efforts, I’m directing an accelerated development and release of JP 3-24, Counterinsurgency Operations (COIN). This joint publication will address the big ideas of COIN . . . providing overarching and enduring guidance, while capturing the means by which the interagency and others contribute to this critical mission.10

A critical outcome of joint doctrine’s role in synchronizing multiple efforts across multiple domains and organizations to ensure unity of effort was also captured in DOD support to the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID)-led Ebola response efforts in West Africa. In that case, existing processes and policies for dealing with an international health crisis such as a regional infectious disease epidemic were initially not well defined. A fundamental understanding on how multiple civilian organizations function, to include their “rules-based approach” and how to incorporate it into DOD joint doctrinal framework, is crucial to solving complex and dynamic challenges. Integrating civilian perspectives into joint doctrine will provide a more holistic comprehension of how to plan, coordinate, and build synergy with all stakeholders.

The present phase captures training, exercises, and ongoing military operations that reinforce or identify new tasks to be performed. The Chairman’s Exercise Program Division is responsible for increasing civilian organization participation through DOD training and exercise events and an annual integration and exercise workshop. Workshop forums provide excellent opportunities for DOD and civilian organizations to share approaches and discuss training events that enhance readiness, in addition to deepening relationships, partnerships, and overall crisis response preparedness.

In 2014, civilian organizations had over 200 individuals participate in DOD training and exercise events. To help expand the concept of integrating with civilian organizations, the Joint Staff J7 teamed with the United States Institute of Peace to design an interorganizational tabletop exercise (ITX). The first ITX in fiscal year 2014 included participants from 15 U.S. Government organizations and 11 other civilian organizations with the purpose of increasing cooperation and effectiveness among organizations operating in a complex crisis. When planning such exercises, it is important to include civilian organizations early during the “joint event life cycle”11 process to ensure achievable military and civilian training objectives are identified for both entities.

In support of joint training events and exercises, a menu of tasks in a common language known as the Universal Joint Task List (UJTL) serves as the foundation for joint planning for military operations. Joint doctrine is directly aligned with the UJTL as each task is currently mapped to a primary JP at its lowest appropriate level. UJTL language and terminology must be consistent and compliant with existing joint doctrine language and terminology. Specific event training tasks or objectives and UJTLs are both essential elements of standardizing the fundamental tasks that serve to prepare and maintain joint force capabilities at their expected levels of performance.

The future phase explores new operational methods, organizational structures, and systems for employment. The absence or lack of depth of joint doctrine in a specific situation may indicate that the joint force has encountered a situation without previous experience.12 In that case, joint concept development aids adaptation by providing solutions for compelling, real-world challenges for which existing doctrinal approaches and joint capabilities are deemed underdeveloped. Joint concepts are guided by potential future threats and provide the basis for joint experimentation, whereas joint doctrine provides the basis for education, training, and execution of current joint operations.13 Approved joint concepts provide important potential sources of new ideas that can improve and eventually be incorporated into joint doctrine. Likewise, joint concepts inform studies, wargames, experimentation, and doctrine change recommendations.

An example of joint concepts incorporating lessons learned and impacting joint doctrine is the Joint Concept for Health Services, which stemmed from Iraq and Afghanistan combat operations and medical integration in the early 2000s. The medical community’s performance was impressive and contributed to the highest survival rate during wartime in recorded history. Although the military medical community made significant strides, it did not institutionalize the many advances in medical operations achieved through collaboration in the war zone. This debate is contributing to the revision of JP 4-02, Health Services.14 Another example showing the impact on the joint doctrine hierarchy is the Joint Operational Access Concept (JOAC):

the JOAC focuses on the ability to overcome anti-access and area-denial challenges and project military force into an operational area with sufficient freedom of action to accomplish the mission. Implementing the JOAC currently is a comprehensive, multiyear effort managed by the Joint Staff Joint Force Development Directorate (J7) in conjunction with other Joint Staff directorates, combatant commands, military Services, and defense agencies. The joint doctrine contribution to the effort involves potential changes between now and 2020 to at least 35 JPs that span all joint functions.15

Finally, similar to joint doctrine, joint education provides the foundation for all phases within the spectrum of joint force development. Joint education is linked to joint doctrine in that all U.S. military education curricula must be doctrine-based and should reflect the deliberate, iterative, and continuous nature of joint force development.16 Joint curricula should include approved joint concepts and the most recent observed lessons from across the joint force.17 The importance for military officers to understand their leadership and cooperation roles beyond warfighting is best captured by the 50th Commandant of the U.S. Army War College, Major General William R. Rapp:

developing military leaders who are competent in the political environment of national-security strategy decisionmaking is vitally important. It requires a broad revision of talent management among the armed Services. Developing strategic mindedness goes beyond operational warfighting assignments and simply “broadening” the officers by sending them to fellowships or for civilian graduate degrees, though both are valuable. Assignments that increase the leaders’ understanding of the interagency decisionmaking process and of alliance and coalition relations are critical.18

Thus, the synergistic value of joint doctrine and joint education lies in their ability to serve as a connective link or common thread through all joint force development functions and to provide a common framework for large, complex organizations—such as the joint force—from which to operate and adapt to new conditions in the operational environment. Given the continued importance of whole-of-government approaches during all phases of joint operations, there may be substantial value in joint force sponsorship of an implementation plan on interorganizational cooperation across the U.S. Government to identify gaps and highlight the potential benefits of sustained unity of effort across the spectrum of operations.

Haiti’s Minister of Health looks at rash on young Haitian girl during U.S. Army Medical Readiness Training Exercise in Coteaux, Haiti, April 2010 (U.S. Army/Kaye Richey)

Civilian Perspectives and Joint Doctrine Solutions

During a JP revision or creation, the joint doctrine community conducts an intensive review of potential tasks and assembles those tasks into best practice. Each JP within the joint doctrine hierarchy serves as a framework that provides authoritative, but not directive, guidance. The joint doctrine framework plays a vital role for the joint force by integrating capabilities integral to military operations. As a result, different organizational approaches to integration present distinct challenges to incorporate civilian perspectives into joint doctrine development. Despite this challenge, the best interests of the joint force are served by deliberate efforts to overcome these challenges and integrate civilian participation into joint doctrine development.

In similar fashion to the military sources for joint doctrine, interorganizational cooperation can inform development of joint and Service-specific capabilities. In October 2011, the Chairman issued a task to ensure the Joint Staff captured the experience gained from over the last decade of war (DOW).19 In response, the Joint Staff J7 reviewed over 400 findings and best practices from 2003 to date and sorted them into strategic themes. The studies included information from a wide variety of military operations such as major combat operations in Iraq, to counterinsurgency in Afghanistan and the Philippines, to humanitarian assistance in the United States, Pakistan, and Haiti, to studying emerging regional and global threats. The prevailing strategic themes asserted the value of a deliberate effort by the military to identify and consider civilian perspectives during the planning, execution, and transition of operations.

Four of the DOW themes are particularly relevant to reinforce the importance of incorporating civilian concerns into military objectives: interagency coordination, understanding the environment, transitions, and adaption. From these lessons we learned that:

- interagency coordination emphasized the difficulty with synchronizing and integrating civilian and military efforts at the national level, in particular during the interagency planning cycle

- understanding the environment implied assessment of the enemy threat as well as aspects of both the civilian population and friendly forces

- transitions spoke to the importance of looking beyond near-term military goals to account for the factors that will contribute to enduring success of overarching political objectives

- adaption recognized the fact that regardless of the operational foundation provided by joint doctrine, the realities and conditions on the ground combined with a “thinking enemy” will require adaption.

As the Chairman originally stated, we must “make sure we [the military] actually learn the lessons of the last decade of war.”20 Therefore, these themes must continually be assessed for integration into joint force development and serve as an enabler to build a more responsive, versatile, and affordable force.21 Underpinning the themes are challenges to interorganizational cooperation as viewed by civilian organizations working with the military in three categories—that is, people, purpose, and process. For the most part, the issues raised by civilian organizations were not new, but continue to be raised with seemingly no resolution.

The people category speaks to communication as the cornerstone for subsequent successful mission completion. Communication challenges exist (for example, understanding doctrine-based and rules-based workforce terminology as well as civilian collaborative and military command relationships22); however, more frequent or routine contact that includes positive personal interaction could accelerate the process of building interpersonal relationships and trust.23 Two ongoing efforts illustrate tangible approaches through which joint doctrine seeks to provide solutions for building trust relationships among diverse groups of people. First, the idea for “interorganizational coordination days” originated with the collaboration conducted between military and civilian organizations during the 2013 revision of JP 3-24.24 Interorganizational coordination, as a collaborative process led by the Joint Staff J5, J7, and the Center for Complex Operations at the National Defense University reinforced the establishment of a formal interorganizational coordination mechanism for joint doctrine revision. Second, the Joint Staff recognizes the value of more routine socialization of joint doctrine with civilian organizations, which are integral parts of a complex global environment. It is imperative for the joint force to consider all aspects of specific operational environments. While threats to the joint force will obviously be paramount in any military commander’s mind, consideration of the contributions of nonmilitary organizations that routinely operate parallel to the military’s effort will serve all organizations in the achievement of their objectives. Proactive outreach efforts such as these seek to broaden the military’s perspective on interorganizational cooperation through an exchange of experiences across multiple interagency organizations and professional education libraries.

The purpose category is centered on where to settle higher level policy disparities to align objectives, the importance of liaisons and advisors in civilian and military organizations, and on where military personnel can best contribute. Understanding roles, responsibilities, and the operating environment is essential in order for the military to effectively establish and work within a humanitarian coordination framework. In humanitarian and disaster relief situations abroad, USAID is the lead Federal entity for U.S. Government efforts. However, they routinely require military resources to achieve the immediate needs, especially in complex, time-sensitive responses. Following their assessment of a situation, USAID often looks to military organizations to assist with capabilities they do not possess, typically in areas such as airlift and logistics. Over the past 10 years, this has been the case during Operations Unified Assistance in Myanmar, Unified Response in Haiti, Tomodachi in Japan, and most recently Sahayogi Haat in Nepal. In each instance, the military responded with specialized capabilities and significant logistical support to the lead organization. As a bridge to DOD, USAID recently published its new policy on cooperation with the Defense Department.25 From a joint doctrine perspective, JP 3-29, Foreign Humanitarian Assistance, was designed to assist a joint force commander and his staff during such operations.26 Building domestic relationships and trust with local communities, the Federal Emergency Management Agency leads U.S. Government relief efforts including defense support,27 while DOD’s Innovative Readiness Training policy provides hands-on training opportunities for military Servicemembers that simultaneously addresses medical and construction needs of local communities.28

The process category involves developing an awareness of organizational cultures so that problems associated with duplicative efforts and faulty assumptions can be minimized through interagency cooperation. Memoranda of agreement (MOA) and understanding (MOU) as well as a “terms of reference” are good foundations for shared processes; however, an institutional-level understanding of civilian organizational cultures provides the best cornerstone for successful interaction. DOD’s Promote Cooperation program is one effective means of achieving interagency cooperation through planning.29 Also, the attempt by DOD with the Department of State and USAID in 3D Planning Group and Guide development efforts highlighted the need to bridge cooperation at the highest levels of those organizations.30 The future challenge for successful interorganizational cooperation is to expand participation mechanisms beyond planning frameworks into areas such as joint force or civilian workforce development.

The combination of joint doctrine, education, and training plays a critical role in communication to military leaders that civil-military relationships must be more cooperative than competitive. Ultimately, there is more to gain from cooperation than by stovepiping each organization’s efforts. The establishment of interorganizational offices within combatant commands, such as joint interagency coordination groups and joint interagency task forces within a theater of operations can benefit all organizations. These organizations provide a focal point for cooperation and information-sharing and enhance planning and execution of actions across the range of military operations. The synergy generated through the combination of military capabilities and resources with civilian organizations is an effective whole-of-government approach that helps break down false barriers and achieve objectives. Although the tasks associated with harnessing the capabilities of various entities can be challenging, the end results help achieve both political and military objectives.

There are joint doctrine solutions that help fill gaps in routine planning, training, and coordinating for cooperation with civilian organizations. Current revision of several Joint Publications (JP 3-0, Joint Operations; JP 3-07, Stability Operations; JP 3-08, Interorganizational Coordination; and JP 5-0, Joint Planning31) highlights the need for improving the degree of institutional-level understanding between the military and civilian organizations. For example, JP 5-0 plays a key role in passing on the lessons of an iterative dialogue to planners at all levels of the military. Systems such as the Adaptive Planning and Execution system facilitate that dialogue and its associated cooperative planning efforts.32 The development of a dedicated Web site to educate military personnel on civilian organizations via the Joint Electronic Library Web site allows searches of strategic plans, certain policies and frameworks, and provides a repository of interorganizational MOA/MOU to build the joint force’s awareness of existing relationships with civilian organizations. In conjunction with these processes, the Joint Staff developed a new format for JP 3-08 organizational appendices to focus on what a joint force commander should know about civilian organizations to enhance interorganizational cooperation.

One final example of joint doctrine solutions involves the proactive solicitation of nonmilitary feedback. For example, the Joint Staff J7 Joint Doctrine Division conducted an intensive effort to obtain feedback from DOD and civilian organizations regarding the importance each placed on individual JPs within the joint doctrine hierarchy. Efforts such as these seek to identify and build more formal coordination efforts with civilian organizations during joint doctrine development and to provide a means for reciprocal joint doctrine reviews of interorganizational documents.

Joint Doctrine Development Process

Joint doctrine provides the critical framework by which the military can incorporate civilian perspectives on interorganizational cooperation into its operations. Inclusion of civilian perspectives during the joint doctrine development process provides civilian organizations with an opportunity to create awareness regarding their perceived roles, capabilities, and organizational culture of their expectations, to build relationships, and to educate and inform the entire joint force—from inside the institutional level. The joint doctrine development process is managed by the Joint Staff J7 and includes the joint doctrine development community, which is primarily composed of DOD organizations and has informally expanded to provide access to civilian organizations inside and outside the U.S. Government.33

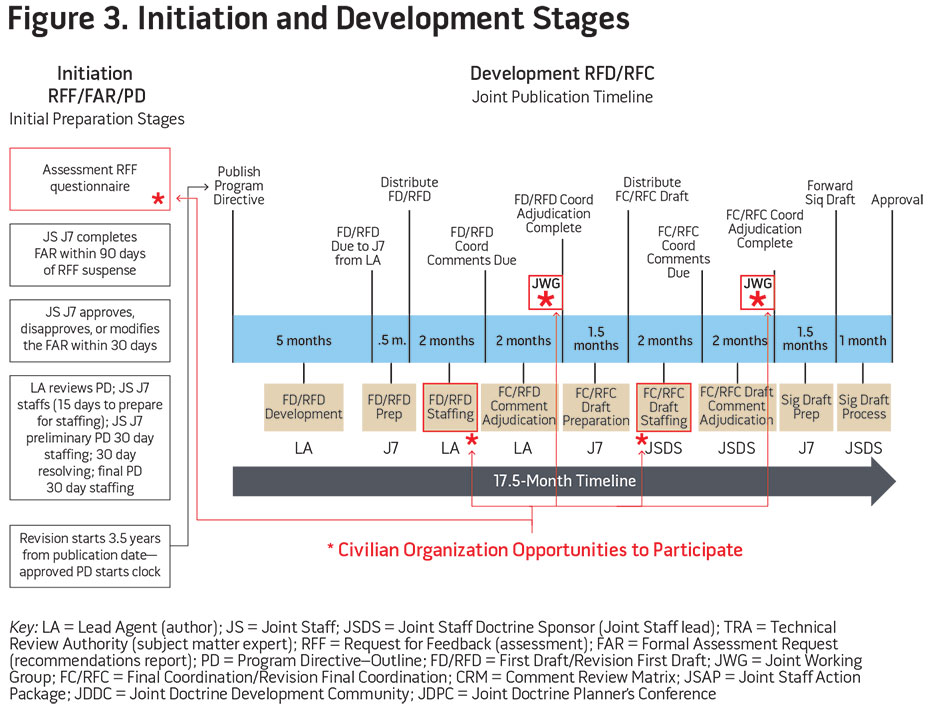

Joint doctrine is coordinated externally during two of the four stages of the joint doctrine development process. The average life cycle of a JP is 5 years with the most influence from civilian organizations developed during the initiation and development stages.34

Within the initiation and development stages, there are multiple points of entry where civilian organizations could influence actual joint doctrine text development (see figure 3). Providing feedback during the initiation stage via the request for feedback (RFF) questionnaire ensures that civilian perspectives will be vetted and socialized early in the joint doctrine development process. The output from the RFF questionnaire is a formal assessment report, which acts as a guide to structuring the JP that provides recommended themes and courses of action for the lead author and Joint Staff doctrine sponsor to use during the writing process. Once the initiation stage is complete and the process that develops the JP outline—known as the program directive (PD)—is solidified, civilian organizations have four other recommended opportunities within the 17.5-month development stage to provide perspectives: first draft comments, first draft working group, final draft comments, and final draft working group.

Once the development stage is complete, the JP is staffed for approval and then is published.

Conclusion

The Chairman is the senior military advisor to the President and Secretary of Defense and is legally obligated to provide “independent” military advice.35 Joint doctrine provides the foundation for all military advice and recommendations provided by the Chairman. The joint doctrine development process provides civilian organizations with an invaluable opportunity to influence military decisionmakers at an institutional level. Military operations require both a clear process for decisionmaking and a framework for immediate employment capabilities toward mission objectives. Interorganizational differences and best practices emerge daily, and it is critical to include their perspectives into the joint doctrine revision process. Joint doctrine is not static; it is intended to be revised and adapted in accordance with vetted operational experiences. Civilian employees and military personnel benefit equally from an enhanced understanding of each other’s respective roles and missions. Participation and contribution to the development of each other’s doctrine or rules can assist in establishing mutual understanding, trust, and rapport.

The vast amount of interorganizational operational experiences during the last 15 years, across multiple global geographies, has clearly established and reinforced the necessity of effective interorganizational cooperation. In light of ever-increasing fiscal pressures and evolving strategic priorities, creative means must be explored that could help both civilian and military organizations maintain, enhance, and routinize cooperation in ways that can best support both sides’ goals, objectives, and priorities. JFQ

Notes

1 James C. McArthur et al., “Interorganizational Cooperation I of III: The Interagency Perspective,” Joint Force Quarterly 79 (4th Quarter 2015), 106–112.

2 James C. McArthur et al., “Interorganizational Cooperation II of III: The Humanitarian Perspective,” Joint Force Quarterly 80 (1st Quarter 2016), 145–152.

3 The joint force is unique in that all other Department of Defense elements support it. Throughout this article the term joint force is used to describe U.S. military forces.

4 Joint Publication (JP) 3-08, Interorganizational Coordination, revision first draft (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, December 10, 2014), 13. The following terms are a range of interactions that occur among stakeholders. There is no common interorganizational agreement on these terms, and other stakeholders may use them interchangeably or with varying definitions. Dictionary definitions are provided as a baseline for common understanding. Collaboration is a process where organizations work together to attain common goals by sharing knowledge, learning, and building consensus. Be aware that some attribute a negative meaning to the term collaboration as if referring to those who betray others by willingly assisting an enemy of one’s country, especially an occupying force. Cooperation is the process of acting together for a common purpose or mutual benefit. It involves working in harmony, side by side, and implies an association between or among organizations. It is the alternative to working separately in competition. Cooperation with other departments and agencies does not mean giving up authority, autonomy, or becoming subordinated to the direction of others. Coordination is the process of organizing a complex enterprise in which numerous organizations are involved and bring their contributions together to form a coherent or efficient whole. It implies formal structures, relationships, and processes.

5 JP 1, Doctrine for the Armed Forces of the United States (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, March 25, 2013), VI-3.

6 JP 3-07.3, Peace Operations (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, August 1, 2012).

7 Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Instruction (CJCSI) 5120.02C, Joint Doctrine Development System (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, January 13, 2012), A-2.

8 JP 3-20, Security Cooperation, revision first draft (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, February 11, 2014).

9 CJCSI 5120.02D, Joint Doctrine Development System (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, January 5, 2015), A-4.

10 George J. Flynn, memorandum, “Way Forward for the Revision of JP 3-24, Counterinsurgency Operations,” June 22, 2012.

11 Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Manual (CJCSM) 3500.03E, Joint Training Manual for the Armed Forces of the United States (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, April 20, 2015), E-3.

12 JP 1, VI-9.

13 CJCSI 5120.01C, A-7.

14 JP 4-02, Health Services Support, program directive and revision first draft (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, 2016).

15 Rick Rowlett et al., Joint Force Quarterly 77 (2nd Quarter 2015), 143–144.

16 CJCSI 5120.01C, A-6.

17 JP 1, VI-5.

18 William E. Rapp, “Civil-Military Relations: The Role of Military Leaders in Strategy Making,” Parameters 45, no. 3 (Autumn 2015), 25.

19 Decade of War, Volume 1: Enduring Lessons from the Past Decade of Operations (Suffolk, VA: Joint and Coalition Operational Analysis Division [JCOA], Joint Staff J7, 2012).

20 Ibid., v.

21 Ibid., 2.

22 3D Planning Guide Diplomacy, Development, Defense: Pre-decisional Working Draft (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, July 31, 2012), 47–55; George Katsos, “Command Relationships,” Joint Force Quarterly 63 (4th Quarter 2011), 153–155; “Multinational Command Relationships,” Joint Force Quarterly 65 (2nd Quarter 2011), 102–104; and “The United Nations and Intergovernmental Organization Command Relationships,” Joint Force Quarterly 66 (3rd Quarter 2012), 97–99.

23 David Grambo, Barrett Smith, and Richard W. Kokko, “Insights to Effective Interorganizational Coordination,” InterAgency Journal 5, no. 3 (Fall 2014), 4–5; Bradley A. Becker, “Interorganizational Coordination,” Insights and Best Practices Focus Paper, 4th ed. (Suffolk, VA: JCOA, Joint Staff J7, July 2013), 1; Alfonso E. Lenhardt, USAID Policy on Cooperation with the Department of Defense (Washington, DC: U.S. Agency for International Development, June 2015).

24 JP 3-24, Counterinsurgency Operations (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, November 22, 2013).

25 Lenhardt.

26 JP 3-29, Foreign Humanitarian Assistance (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, January 3, 2014).

27 JP 3-28, Defense Support of Civil Authorities (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, July 31, 2013).

28 Innovative Readiness Training Web site, available at <http://irt.defense.gov/>; Department of Defense Directive 1100.20, Support and Services for Eligible Organizations and Activities Outside the Department of Defense (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, April 12, 2004).

29 CJCSI 3141.01E, Management and Review of Joint Strategic Capabilities Plan (JSCP)—Tasked Plans (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, September 8, 2014), D-2.

30 3D Planning Guide Diplomacy, Development, Defense.

31 JP 3-0, Joint Operations, revision first draft (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, October 8, 2014); JP 3-07, Stability Operations, revision first draft (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, December 9, 2014); JP 3-08; JP 5-0, Joint Planning, revision first draft (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, August 11, 2011).

32 Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Guide 3130, Adaptive Planning and Execution (APEX) Overview and Policy Framework (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, May 29, 2015).

33 CJCSI 5120.02D; CJCSM 5120.01, Joint Doctrine Development Process (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, December 29, 2014), B-1.

34 Ibid., B-6–B-23.

35 Janine Davidson, “The Contemporary Presidency, Civil-Military Friction and Presidential Decision Making: Explaining the Broken Dialogue,” Presidential Studies Quarterly 43, no. 1 (March 2013), 134–137.