Colonel Brent French, USAFR, Ph.D., is the

Individual Mobilization Augmentee to the

Director of Training in the Office of the Assistant

Secretary of Defense for Reserve Affairs.

We should expect increased dependency on the Reserve Component (RC) due to post-sequestration, post–Operation Enduring Freedom force reductions within the Active Component (AC), and simultaneous plans to increase regional alignment throughout the RC.1 RC contribution to all echelons of combatant command planning and execution will expand to allow “military department apportionment of larger Reserve Component formations . . . to Combatant Commander OPLANs [operation plans].”2 Joint force presentation, planning, and administration will, by necessity, be a Total Force endeavor. This prompts inquiry into the current state and future sufficiency of joint competencies within the RC.3 After reviewing the constellation of laws, policies, and practices designed to produce joint qualified officers (JQOs), I believe the current system is serving the AC well but has unintentionally limited the joint potential resident in the RC officer corps to the detriment of the Department of Defense (DOD). In this article, I argue that “joint,” as defined by law and implemented within DOD, has become largely an AC competency and that national security would be better served by developing a new vision for joint competencies as component-neutral.

Soldiers from Minnesota National Guard complete ruck march at Forward Operating Base Gerber, Kuwait, January 27, 2012 (U.S. Army/Trisha Betz)

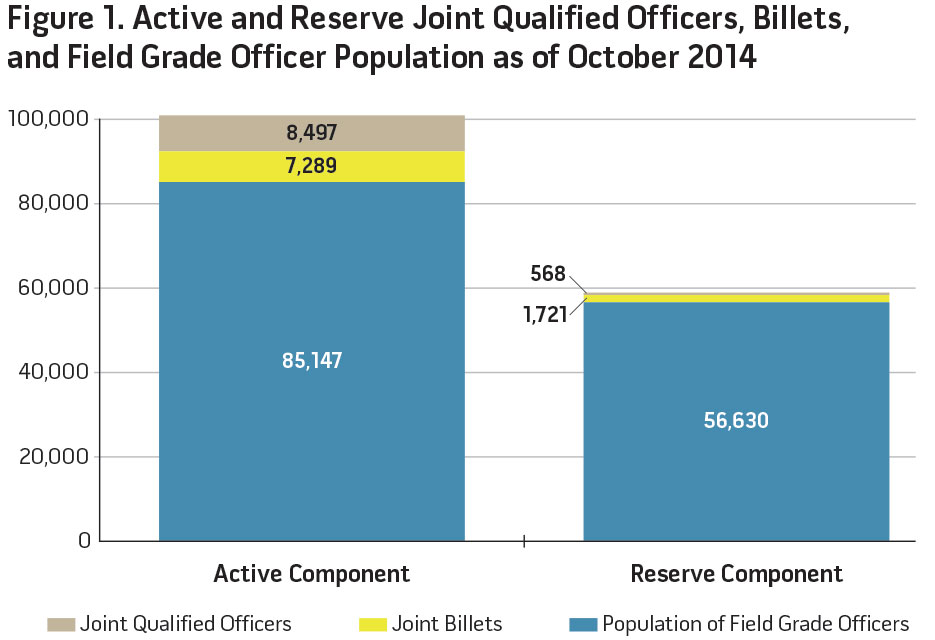

Our goal should be a purple Total Force, but right now the RC is watery lavender at best. There are fewer than 600 joint qualified RC officers out of the 56,630 officers at the O-4, O-5, and O-6 grades actively serving in the Reserve or Guard.4 For every RC joint qualified officer, there are 15 AC joint qualified officers; closing this gap may require modernizing the legacy of the Goldwater-Nichols Department of Defense Reorganization Act of 1986 (GNA) and asking pointed questions about the adequacy of current outcomes. For example, are DOD’s best interests served by practices that segregate by component? Is an 85 percent disapproval rate for National Guard joint experience applications acceptable? Are we doing enough to create an educational and experiential base among the 90 percent of the RC force that serves part time? If we believe DOD is better served by a diffusion of joint competencies throughout the Total Force, then the edges and unintended outcomes of the current joint qualification system merit inquiry with an a priori understanding that both DOD and Congress share responsibility for developing an adaptive force capable of meeting the demands of an uncertain future.

Some argue there is no valid reason for joint expansion within the RC, especially in light of Federal law that requires joint qualification among AC (but not RC) officers prior to promotion to general or admiral.5 The solution to RC jointness, as seen from this perspective, is simple: require joint qualification for RC officers prior to O-7 promotion, and until then there is no real requirement. This logic seems to presuppose that the only reason for becoming a JQO is promotion, and this may be ignoring the intent behind GNA,6 but requiring JQO status for RC general and flag officers may be a reasonable and durable solution to effect change over a multi-decade horizon. It took over two decades to fully implement JQO status as an O-7 prerequisite within the Active Component, spanning the period from GNA in 1986 through the National Defense Authorization Act of 2007, at which time waiving joint qualification for promotion became extremely difficult. Moving toward mandatory joint officer qualification for the RC also needs to account for limited opportunities within the Guard for joint experience due to the way joint matters are currently defined by law and joint positions are arrayed. For example, there are fewer than 150 joint positions for the 21,150 Army and Air National Guard O-4s, O-5s, and O-6s compared with 1,700 joint positions for the 35,480 Reserve field grade officers. The interrelated nature of Joint Officer Management entails complementary combinations of experience and education, and this implies that changing Federal law to make general and flag officer promotion standards the same across components can only be successful if there are structural changes to the joint qualification system.

In the meantime, DOD—especially the Office of the Secretary of Defense’s Officer and Enlisted Personnel Management (OEPM) area, the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) Manpower and Personnel (J1) directorate, the JCS Joint Force Development (J7) directorate, and the Service chiefs—has executed legislative and executive intent to the maximum (as evidenced by the hundreds of thousands of joint-exposed, -educated, -experienced officers and enlisted members over the last 30 years) and continues to stay attuned to future demands of the Total Force. The statutory requirement for RC joint force development comes directly from Federal law, specifically that joint education and experience “shall, to the extent practicable for the reserve components, be similar to [AC Joint Officer Management].”7 While I suggest there are emerging opportunities to apply this law for the betterment of national security, there is ample evidence of DOD’s pursuit of this mandate.

For instance, tremendous effort has gone into creating and sustaining an RC-feasible joint education pathway (Advanced Joint Professional Military Education, or AJPME), and, on a smaller scale, DOD RC promotion boards began reporting joint qualification statistics to Congress ex post facto in a manner similar to AC reporting.8 DOD has also been successful in promoting a culture that values joint education and experience, evidenced, for example, in the way RC officers are mentored to understand that joint exposure will help their careers, their Services, and the broader enterprise. Selective screening for joint billets reinforces this message.

The degree to which DOD has enculturated jointness within the RC provides a foundation for enhancing the Joint Officer Management system. While some changes to the joint development process require amending current statutes, a number of areas are under DOD control. For example, tenure standards for part-time RC members serving in joint billets are a matter of DOD policy, as are joint experience application and approval processes. Improving jointness across the force continues to be a shared responsibility between Congress and DOD, and to the degree DOD can enhance jointness within the RC under the “extent practicable” clause in current Federal law, the need to depend solely on Congress for reform is obviated, although close coordination and support should be (and have been) the norm.

U.S. Soldier assigned to 237th Support Battalion of Ohio National Guard provides perimeter security during medical evacuation training exercise at Fort

McCoy, Wisconsin, July 21, 2013 (U.S. Army/Darryl L. Montgomery)

A discussion of specific concerns about RC jointness needs a caveat, namely, that we risk preoccupation with the tactical at the expense of the strategic. Strategic inquiry into joint force development must include discourse on the range of competencies the joint development system should inculcate in our future officer, enlisted, and civilian workforce, and this includes reexamining GNA from a 21st-century vantage point. For example, Federal law defines the types of partner organizations DOD can work with to be eligible for joint credit, and the law currently recognizes collaboration with people from other military departments, nonmilitary departments and agencies of the United States, foreign military forces or agencies, and nongovernmental persons or entities.9 It is possible that a more inclusive definition could account for current organizational arrangements unanticipated even a decade ago (the current list of eligible partners became law in 2006), such as Federal DOD support for state governments and their agencies, or future arrangements we are currently unable to predict. For example, the desired behaviors implied by partnership, joint integration, and collaboration include interdependence, cooperation, and spanning beyond organizational boundaries, competencies critical to successful national security strategy. I suspect our future will demand new levels of interconnectedness among Active and Reserve components in ways not envisioned during the GNA era nor fully anticipated by Total Force and Abrams Doctrine proponents in the 1960s.10 The ability to work across component boundaries is the same ability needed to work in joint environments; it is no accident that then–Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS) General Martin E. Dempsey discussed cross-component relationships in the same breath as joint force development, stating that “we will reexamine and revise the relationships among Active, Guard, and Reserve forces of our military. And we will need to be even more joint—pushing interdependence deeper, sooner.”11

This article endeavors to reexamine cross-component relationships within the context of joint interdependencies, specifically addressing RC progress on joint education, joint billets and the standard path to becoming a joint qualified officer, the experience path to joint qualification, and the need to acknowledge cross-component experience.

RC Joint Officer Production

Officers become joint qualified through a combination of education and experience. The educational component of the qualification system emphasizes longitudinal development. Cadets are given joint awareness courses, field grade officers (those in grades O-4, O-5, or O-6) attend joint courses that last from 10 to 40 weeks, and new general and flag officers attend a 55-week joint program. The experience component of the joint qualification system recognizes assignments in predesignated joint billets (thus creating the standard path to accumulating experience) or emergent and unanticipated jobs related to joint matters for which the member must apply for credit after the fact (known as the experience path).12 When a field grade officer completes joint education and gains sufficient joint experience, he or she may request to become a joint qualified officer.

The majority of Active Component JQOs earn their credentials by attending a 10-week residential course and serving 3 years in a pre-identified billet at a combatant command.13 The part-time nature of Reserve Component service precludes one-size-fits-all pathways, and DOD has over time successfully advocated for RC specific provisions such as full- and part-time joint billets for the Reserve and Guard,14 as well as creating a 40-week low-residency joint education program as an alternative to the aforementioned 10-week residential course. Furthermore, policies consistent with the idea articulated in the 2005 CJCS Vision for Joint Officer Development and reinforced by the 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR) to “recogniz[e] joint experience whenever and wherever it occurs in an officer’s career”15 are important to RC members who are five times more likely than their Active peers to become joint qualified through the experience path.16 Moreover (as of 2010), RC members can receive credit for joint work done as civilian government (Federal, state, or local) employees,17 all of which points to the foresight of the Joint Officer Management community.

Despite elements of the joint qualification system that support recognition of RC jointness, these investments seem to have fallen short of producing significant numbers of RC JQOs, and the Active Component to have an unintentional monopoly on joint officers to the detriment of the quality and quantity of alternatives available to combatant commands and the CJSC. Low RC JQO production has created a situation wherein the AC has 94 percent of DOD JQOs despite having 81 percent of all joint billets. Another way of looking at this imbalance comes from contrasting the number of JQOs with the pool of eligible officers: 10 percent of all AC field grade officers are joint qualified versus 1 percent of all RC field grade officers (see figure 1).

One might anticipate proportionately higher AC qualification rates because there are four times more joint positions in the AC than the RC (thus creating more opportunities to earn qualifying experience), but current ratios indicate we may be overproducing JQOs within the Active Component or underproducing JQOs in the Reserve Component. This is potentially problematic given that DOD intent is to diffuse jointness per the 2005 CJCS Joint Officer Development Vision. With the understanding that joint billets grant experience leading to JQO designation (as distinct from critical joint billets that require JQO status as a prerequisite), we can compare JQO production rates to billets by component to better understand production rates. As one element of this comparison, the AC has 1.17 JQOs for each joint position as opposed to the RC’s 0.33 JQOs for each position. By applying the AC ratio to RC positions, we find a shortfall of 1,438 RC JQOs or, conversely, a surplus of 4,833 AC JQOs. These figures are not meant to be taken literally because component differences (for example, assignment rotations) justify some disparities, but the gap indicates a system working well for one component but underserving another, and this gap continues to widen. During fiscal year (FY) 2014, the RC produced 133 JQOs while the AC credentialed nine times as many (1,195); although this gap is in accordance with current law and policy, it should prompt us to ask if DOD’s future is best served by design parameters that contribute to these qualification rates.

JQO production can be further segmented to reveal gaps within the Reserve Component itself. Full-time RC members are becoming joint qualified at higher rates than their part-time counterparts. Nearly 40 percent (51) of the 133 RC JQOs credentialed in FY14 were full-time RC members, noteworthy because full-time members are only 10 percent of the overall RC.18 This hints at the possibility that the part-time segment of the RC may be on the margins of the joint qualification system as currently encoded in law and policy.

Three conclusions can be drawn from the preceding discussion. First, AC JQO production is robust and outpaces RC JQO production nearly 10 times over. Second, portions of the RC—full-time members—are well served by today’s joint qualification system and are gaining sufficient joint experience, education, and credentials. Third, the system that is working relatively well for the AC and full-time RC does not appear to be working as well for the part-time RC, and this creates opportunities to improve the system for greater effect by considering the way experiences are credited, the way education is earned, and the way joint is defined.

The Experience Path Is Critical for the RC

The practicum component of becoming a JQO can be satisfied through the standard path (filling a full-time joint billet for 3 years) or an experience path through which people self-nominate relevant experiences for credit. The experience path offers a flexible counterpoint to the occasionally cumbersome and bureaucratic joint billet approval and validation process. RC members who serve full time in a joint billet for 3 years do not need to go through a boarding process for credit, nor do part-time RC members who serve in a joint billet for 6 years for 66 days a year (an additional 30 days per year in addition to normal drill). The “Six and 66” rule changed in 2014 (discussed in the next section), and part-time RC members are allowed to satisfy experience requirements through 3 years of normal drill (36 days per year, or 12 weekends plus a 2-week annual tour) plus an additional 10 experience points. This effectively means the experience path is the only pathway available to RC members who serve part time, and it heightens the importance of this program—conclusions supported through FY14 production data.

The table shows pathways for the 1,195 AC and 133 RC officers who became JQOs in FY14; 84 percent (1,104 out of 1,328) earned their credentials through the standard path, and 16 percent (218 out of 1,328) became qualified through experience. While the experience path is not especially important for AC officers—only 11 percent (137 out of 1,195) earned joint qualification through this method—the opposite is true for the Reserve Component. The majority (61 percent, or 81 out of 133) of the RC officers who became joint qualified in FY14 got there through the experience path. The experience path is even more critical for part-time RC members; 77 percent (63 out of 82) became JQOs through this self-nomination process.

The importance of the experience path to part-time RC officers implies that investments made in simplifying the application process, enhancing technology used to apply and manage experience points, and streamlining applications and supporting documentation directly benefit tens of thousands of RC members as well as the net beneficiary of Joint Officer Management: DOD. It is possible that joint experience opportunities may shrink in a post–Operation Enduring Freedom security environment, and this may lead to a concurrent withdrawal of investment in enhancing the experience path application and approval process. In this case, we should do so only cautiously and with full awareness of the implications for RC officers and the future of RC jointness.

The End of the Six and 66 Rule

In 2007, DOD published the “Six and 66 Rule” for part-time RC members, which stipulated that joint experience credit could be satisfied by serving in a joint position for 6 years and performing an extra 30 days per year in addition to the 1 weekend a month, 2 weeks per year obligation (for a total of 66 workdays, hence the name for the rule). DOD justified this policy by asserting that “RC officers who perform part-time duty generally do not gain sufficient joint knowledge and experience within [normal] . . . tour length requirements.”19 While this may be true, it may not be, and the lack of joint competency assessments makes this impossible to gauge. While Six and 66 may have enhanced the jointness of the Servicemember, the costs were ultimately unsupportable. The Services lost an individual for 6 years, fully encumbered funding for an additional 30 days for each of the 1,700 part-time joint billets had the potential to surpass $10,000,000 a year,20 and RC joint qualified officers serving as of October 2013 became JQOs through the Six and 66 path.21

In 2014, DOD changed the Six and 66 Rule to grant full experience credit for 3 years of service in a joint billet at 36 days per year plus 10 additional experience points (“Three and 10”). The principal benefits of the change include freeing up assignment rotations, which potentially gets more people into joint billets and grants the Services more opportunity to develop Service competencies, and removing the requirement for the extra 30 days of service per year avoids a large funding obligation. I am less certain about a Servicemember’s opportunity to earn 10 experience points. A 3-and-a-half-month tour in a combat zone working on joint matters may be the shortest way, and the noncombat pathway might involve a mix of joint exercise planning, taking courses such as the Reserve Components National Security Course, and finding a way to do 5 months of full-time work in a joint billet. On the positive side, there are a variety of ways to earn 10 points; however, this flexibility may also obscure the path for Servicemembers and their mentors. While we can anticipate an increase in RC JQO production as a result of the new policy, the rate of increase is difficult to anticipate, and simplifying the process should be a matter for future inquiry. The change from Six and 66 to Three and 10 is a net gain for DOD, and it should be supported by new attention and investment in the process that grants experience credit.

Variance by Component in Approval Rates for Experience Credit

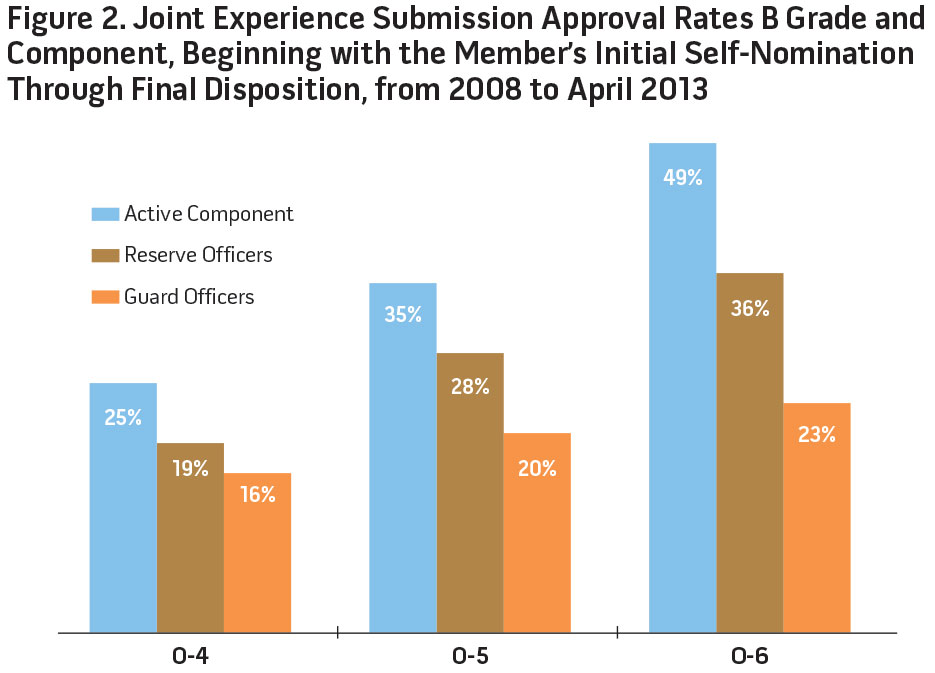

In 2013, over 80 percent of new RC JQOs earned their credentials through the experience path rather than the standard path, while the opposite was true for new AC JQOs; 88 percent earned credentials through the standard path. As important as the experience path is to RC members, analysis of 5 years’ worth of applications for joint credit shows the RC lags behind AC approval rates. Understanding why this occurs has not been fully explored and should be shouldered in the future. There are a number of possibilities, including differences in process mentoring, experience in writing applications, qualitative differences in experiences, and subjective factors, so my purpose is descriptive, not diagnostic.

The National Guard is the least successful when applying for experience credit. Figure 2 shows the results of 30,363 self-nominations that were started by Servicemembers beginning in 2008 through April 2013. The overall approval rate on National Guard applications was 15 percent (422 approved out of 2,836 applications) versus 23 percent and 21 percent for the Active Component and Reservists, respectively. One plausible explanation is the lack of opportunity to work joint matters at the state level (which is extremely difficult the way joint matters are currently defined in the U.S. Code), but I suspect Guard officers are applying for experiences gained during contingency operations outside of the United States, although this is speculative and the situation merits further investigation. Our collective goal should be a joint experience crediting system that works well irrespective of component.

Separate but Equal Education

Officers are required to complete joint education before they are credentialed as JQOs, and half of Active Component officers satisfy this through a 10-week residential course run by the Joint Forces Staff College called the Joint and Combined Warfighting School (JCWS), while the other half participate in National Defense University or senior Service school residential programs. JCWS expanded in 2012 by allowing the course to be delivered to four 20-person classes per year adjacent to the two combatant commands at MacDill Air Force Base on a trial basis.22 The intent behind this program was to expand joint professional military education (JPME) Phase II throughput, empower combatant commands to choose attendees, and reduce student time away from family.23 Furthermore, expanding this program promotes better combatant command outcomes and the diffusion of joint knowledge, and the logical investment evolution seems to be from centralized and residential (pretrial) to decentralized and residential (the trial itself) to decentralized with blended-residential (distance education, which exists today as Advanced JPME).

Advanced JPME (AJPME) is a 40-week blended program (combining distance education with 3 weeks of residency) and is attended exclusively by RC officers.24 AC officers do not attend AJPME because it does not give them joint education credit despite a curriculum virtually identical to JCWS. AJPME is unable to award the type of credit (JPME Phase II) AC officers need to become joint qualified officers. One of the main barriers preventing AJPME from becoming a JPME Phase II granting program is a 2004 law that requires Phase II programs to include 10 weeks of residential sessions. While it is possible that this law will change in the next several years, this outcome is uncertain; thus, it is worth understanding the arguments for running an integrated program.25

The first justification for integration comes from the logic of the Total Force. We fight as a team, so we should train and educate as a team, and the Commission on the National Guard and Reserve articulated this perspective in its 2008 final report with comments about AJPME:

No active component officers attend the program. Such segregation is obviously counter to efforts to integrate the total force: indeed, the long-standing cultural differences between the active and reserve components heighten the importance of incorporating officers into the same programs, which can provide common experiences [emphasis added].26

The Total Force justification has been argued by a number of authors and echoed in QDR commitments for RC and AC equity. Then–Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Admiral James A. Winnefeld, Jr., commented that “the Department must continue to emphasize cross-component education and interaction.”27 The Total Force argument has been countered with references to current law (mentioned above), and the status quo has also been supported by quality concerns about degrading joint educational and enculturation outcomes.

The quality argument may have been valid at one time, but is difficult to sustain in light of ongoing AJPME program improvements. The Joint Forces Staff College shares faculty and content across the 10-week residential JCWS and AJMPE. The AJPME program drew significant praise during its recent accreditation, and AJPME program managers have reduced student rollback to 10 percent or less per class despite a demanding 40-week commitment. These all evidence AJPME’s merit. From a faculty and administrative viewpoint, program administrators see no major challenges if AC officers were allowed to attend AJPME, and they report anecdotal evidence of AC members interested in attending AJPME due to the flexible nature of the blended curriculum. If AC officers were allowed to attend AJPME, there is a risk that Services could allocate all of their AJPME quotas to AC officers, thus crowding out the RC and undermining the original intent behind AJPME. How this gets resolved is a topic for future inquiry.

If Active Component officers attended AJPME and received full joint education credit, we might expect cost savings (if the low-residency AJPME was used in lieu of a 10-week residential course for selected AC members) and better acculturative outcomes through cross-component interaction. In addition, AC force development managers would have a third and more flexible option to satisfy joint education requirements. One might expect ongoing and accelerated improvement of AJPME quality because of the inclusion of a new community and the possibility of growth commensurate with demand, and this integrated path could create new opportunities for RC officers to attend in-residence seats vacated by AC or to participate in expanded AJPME programs. The Services (responsible for allocating seats across their components) will gain a new option for routing AC officers through JPME Phase II and can, if they choose, send more high-potential RC officers to JPME Phase II in residence, thus affording greater latitude in Total Force development. While there are structural inhibitors to sending RC members in residence en masse (thus necessitating AJPME), there may be greater RC member willingness to attend school in residence due to a number of factors, including stronger laws to protect civilian jobs and increased competition for promotion due to force reduction. As a matter of future inquiry, each Service can independently verify the RC appetite for school in-residence while staying within the bounds of expanding jointness to the extent practicable for the RC.

In summary, integrating AJPME will be a multiyear endeavor and will require congressional support, persistence within DOD, and Service cooperation, but the payoff will be better joint outcomes across all components.

Redefining Joint and Rewarding Cross-Component Collaboration

The strategic issue that transcends discussion about joint education policy, the joint experience credit process, and other Joint Officer Management implementation issues is this: we assume cross-component compatibility at our own peril and are subject to the fallacious beliefs that necessitated GNA in the first place, especially during fiscally lean periods and in the absence of extended contingency operations. The boundary-spanning practiced when Active, Reserve, and Guard members stand shoulder-to-shoulder and focus on common objectives increases the likelihood of spanning and cross-domain success in other arenas. Boundary-spanning is a capacity unto itself; it is one answer to General Dempsey’s 2014 challenge “to reassess what capabilities we need most, rethink how we develop and aggregate the Joint Force, and reconsider how we fight together.”28 Redefining “joint” to include cross-component work acknowledges existing forms of collaboration as well as allowing room for emergent relationships (for example, Reserve and Guard partnerships during Hurricane Sandy relief operations). To this end, it is worth considering policies to promote this strategic vision and provide incentives for cross-component work as a long-term force development issue.

DOD has evolved beyond the original inter-Service cooperative mandate of GNA, and Congress has expanded the boundaries of joint beyond sister-Service work. For example, the 2006 QDR strongly advocates for interagency competencies because:

much as the Goldwater-Nichols requirement that senior officers complete a joint duty assignment has contributed to integrating the different cultures of the Military Departments into a more effective joint force, the QDR recommends creating incentives for senior Department and non-Department personnel to develop skills suited to the integrated interagency environment [emphasis added].29

This line of reasoning has helped shape new meanings of force integration, with the implication that officers could earn joint credit by working on joint matters with people from other military departments, nonmilitary U.S. departments and agencies, foreign military forces or agencies, or nongovernmental entities. We have institutionalized an Army (circa 2000) concept known as Joint, Interagency, Intergovernmental, and Multinational (JIIM), and by 2008 JIIM had become operational doctrine as well as a key tenet of military leadership development. The ability to work across organizational boundaries and build networks outside of normal hierarchies30 has become a key component of the Chairman’s Capstone Concept for Joint Operations, wherein the Chairman urges DOD to:

Oregon National Guardsman assigned to 1186th Military Police Company provides security during mission at National Training Center at Fort Irwin,

California, August 23, 2015 (U.S. Army/W. Chris Clyne)

become pervasively interoperable both internally and externally. Interoperability is the critical attribute that will allow commanders to achieve the synergy from integrated operations this concept imagines. Interoperability refers not only to materiel but also to doctrine, organization, training, and leader development. Within Joint Forces, interoperability should be widespread and should exist at all echelons. It should exist among Services and extend across domains and to partners.31

Although use of the term IIM—interagency, intergovernmental, and multinational—has been subsumed under the term interorganizational as of 2011 with the publication of Joint Publication 3-08, Interorganizational Cooperation During Joint Operations, the concept remains vital to the way the Nation projects national and military power.

The way we define integrated forces is only half of the joint matters equation, and the content, type, and level of the work performed are given equal weight within the joint qualification system. While joint education is premised on the longitudinal layering of new knowledge (constructivism), our ability to collaborate with others is assumed. For example, imagine two Army officers (with no previous joint experience points) working on a North Atlantic Treaty Organization staff, one with previous tactical experience as part of an Alliance-heavy Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force during Operation Enduring Freedom and the other without. Which officer is primed to make an immediate impact, to apply conditioned knowledge, to have a richer developmental experience? Our current approach seems unable to formally account for experiences at the tactical and operational level, yet these experiences serve as critical building blocks for success at the strategic level. We do not need to scale a cliff when all we need is a ramp.

Although we promote, recognize, and reward our officers for boundary-spanning, we mostly fail to recognize and promote boundary-spanning across components, although this varies by Service. For example, the Marine Corps Inspector-Instructor program puts AC and RC Marines into frequent contact, and the Marine Corps has been able to support (rather than hinder) cross-component flow through the prudent use of promotion policy and cultural transformation. The other Services have their own robust versions of Total Force integration, but none are accounting for, promoting, or privileging work across component boundaries in the same way they account for joint Service collaboration. This is partially due to Federal law that defines “joint” as working with more than one military department, and one might argue DOD is required by law to operate jointly, but we are not required by law to operate as an integrated Total Force in the same way jointness is legislated. DOD and national security may be better served by an alternative arrangement, one that encourages officers and enlisted members to develop boundary-spanning capacity in a joint, interagency, intergovernmental, international, nongovernmental, or Total Force context. The proposed paradigmatic shift is from “JIIM” to “JITIM,” where the “T” stands for Total Force. Conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan put components into constant contact with each other, and despite intentions to increase peacetime use of the RC, we risk regressing into pre-9/11 enclaves unless deliberate efforts are made to value Total Force integration as much as we value multi-Service and interorganizational work.

Conclusion

Developing joint competencies within our Reserve Component officer corps must be embraced as a strategic human resources investment and an essential Total Force enabler because diffusion of joint experience and education gives joint consumers more flexibility and creates cultural preconditions for adaptive success. This matter takes on new urgency in a post-sequestration, post–Operation Enduring Freedom environment, and evidence points to untapped potential within the part-time force that can be harvested through modest financial investment, cooperation with Congress, and a willingness to think critically about the types of capabilities our future force will need.

Soldiers participate in Sapper Stakes, a combined competition hosted by 416th Theater Engineer Command and 412th TEC to determine best combat engineer team in Army Reserve (U.S. Army/Michel Sauret)

If we agree that boundary-spanning is a cornerstone adaptive capability, then there are a number of realities to be examined and alternatives we can generate, including the following: GNA reform, which helps us reconsider what we value; changes to the joint experience crediting system that improve how we account for the things we value in a way that improves outcomes for all components; and possible new ways to improve our joint education system to promote greater inclusiveness and cross-component interaction. There are limits to the amount of enhancements that can be done within the Department of Defense, and congressional will and cooperation will be needed to improve outcomes for the Guard, Reserve, and Active components alike. JFQ

Notes

1 Scott F. Donahue, Randy Buett, and Katherine Numerick, “Implementing Regional Alignment: The U.S. Army Reserve Approach,” U.S. Army Reserve Command White Paper, February 2013; Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (VCJCS) and Assistant Secretary of Defense for Reserve Affairs (ASD/RA), Comprehensive Review of the Future Role of the Reserve Component: Volume I, Executive Summary and Main Report (Washington, DC: Department of Defense [DOD], April 5, 2011). In a March 2013 speech to the House Armed Services Committee Reserve Caucus, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Reserve Affairs (Readiness, Training, and Mobilization) Paul D. Patrick argues our thinking is inflected by “the end of major force commitments to Afghanistan; focus on full spectrum operations in the pivot to the Asia-Pacific region; severely constrained DOD budget for the foreseeable future; inevitable (though not yet fully recognized or admitted) active force structure reductions.” The inevitability of full-time force reductions is due to “the steadily increasing fully-burdened and life-cycle costs of active duty military manpower and the ‘all-in’ support costs of the volunteer force [which] will either drive further reductions in active component structure or result in unwise trade-off[s] among personnel, training and modernization.” See Arnold L. Punaro’s May 6, 2013, memorandum to the Secretary of Defense titled “Strategic Choices and the Reserve Components,” available at <http://rfpb.defense.gov/ Portals/67/Documents/ RFPB_memo_SecDef_re_SCMR_and_QDR_FINAL.pdf>.

2 Patrick.

3 Derived from the Title 10 U.S.C. 38 § 668 (available at <www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/USCODE-2011-title10/html/USCODE-2011-title10-subtitleA-partII-chap38-sec668.htm>) definition of joint matters, joint competencies as used in this article are the knowledge, skills, and abilities required to achieve unified action by integrated military forces, and jointness is a measure of degree. In this article I am using joint competencies, jointness, and joint capacity interchangeably, although there are alternative interpretations. Joint competencies were defined in the CJCS Vision for Joint Officer Development (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, November 2005) as having a strategic mindset, critical thinking ability, and joint warfighting skills, and then-Chairman General Peter Pace sought to “inculcate jointness in all colonels and captains,” 8. Jointness was defined in Margaret C. Harrell et al., A Strategic Approach to Joint Officer Management (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2009), as a set of billet attributes related to joint matters.

4 Margaret W. Burcham, “Memorandum for the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Military Personnel Policy: Joint Staff Input for the Fiscal Year 2014 Annual Report to Congress,” December 2014.

5 Priscilla Offenhauer, General and Flag Officer Authorizations for the Active and Reserve Components: A Comparative and Historical Analysis (Washington, DC: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress, 2007), available at <www.loc.gov/rr/frd/pdf-files/CNGR_General-Flag-Officer-Authorizations.pdf>; Kenneth Olivo, “Reserve Joint Officer Qualification System—Getting it Right,” Strategy Research Project paper, U.S. Army War College, March 2008, available at <www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?AD=ADA478984>. Furthermore, Title 10 U.S.C. 36 § 619a requires joint qualification for Active Component (AC) general officer/flag officer promotion. See <www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/USCODE-2011-title10/html/USCODE-2011-title10-subtitleA-partII-chap36-subchapII-sec619a.htm>.

6 There are at least three perspectives on why DOD seeks to create joint qualified officers (JQOs). One is promotion to general or flag officer. As it applies to the Reserve Component (RC), people argue that since being a JQO is not required for promotion, we should not worry about RC JQO. The second theory suggests JQOs exist to fill critical Joint Duty Assignment List positions; some argue that since there are only 5 critical billets in the RC (compared to 448 in the AC), RC JQO is moot. The third theory suggests all O-6s and higher need to be “inculcated [with] jointness” (CJCS Vision for Joint Officer Development, 8) and JQO is a measure of those fully qualified. Yet another theory seems to use JQO status partially as a thermostat for DOD’s joint temperature, and I am writing from this stance.

7 See Title 10 U.S.C. 38 § 666.

8 See DOD Instruction 1300.19, “DOD Joint Officer Management Program,” available at <www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/corres/pdf/130019p.pdf>; CJCS Instruction 1330.05, “Joint Officer Management Program Procedures,” June 2013, available at <www.dtic.mil/cjcs_directives/cdata/unlimit/1330_05.pdf>.

9 See Title 10 U.S.C. 38 § 668.

10 The Abrams Doctrine soothed fears about moving to an all-volunteer force by suggesting that the proper balancing of Active and Reserve capabilities would ensure future wars could not be fought without the RC, and RC mobilization would bring “the will of the people” into the fight.

11 Martin E. Dempsey, “Moving Forward Together,” Joint Force Quarterly 64 (1st Quarter 2012), 4.

12 A Joint Qualification System primer is available at <http://prhome.defense.gov/ rfm/mppPortals/52/Documents/ RFM/MPP/OEPM/dDocs/JOM%20Fact%20Sheet%20-%2030%20Mar%202010.pdf>.

13 Half of AC members receive joint professional military education (JPME) II through the Joint and Combined Warfighting School per year, 88 percent earn Level III via the standard experience path, and over 60 percent of Joint Duty Assignment List positions are in the combatant commands.

14 The RC has 19 percent of DOD’s 8,999 joint positions. Of the 1,726 RC positions, 361 are full-time billets, of which a third (113) belong to the Guard. Half of the 1,365 part-time positions are Individual Mobilization Augmentees, with the remainder unit-based (Traditional Reservists or Troop Program Units). The Guard does not have any part-time joint duty assignment list positions, according to the Defense Manpower Data Center Data Request DRS64275. See also DOD Instruction 5105.83, “National Guard Joint Force Headquarters—State,” 2011, available at <www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/corres/pdf/510583p.pdf>; Scott D. Legwold and David W. May, “Disjointed: Give Reservists and Guardsmen a True Path to Joint Qualification,” Armed Forces Journal (November 2011), available at <http://armedforcesjournal.com/2011/11/7886381/>; Harry J. Thie et al., Framing a Strategic Approach for Reserve Component Joint Officer Management (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2006), available at <www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/monographs/2006/RAND_MG517.pdf>.

15 Quadrennial Defense Review Report (Washington, DC: DOD, 2010), 54, available at <www.defense.gov/qdr/images/QDR_as_of_12Feb10_1000.pdf>.

16 Burcham.

17 DOD Instruction 1300.19. RC members have submitted over 10,510 applications for joint experience since 2008. The civilian government job (Federal, state, or local) provision has yielded an estimated 10 to 12 applications for credit since 2010, several of which have been approved.

18 Assistant Secretary of Defense for Reserve Affairs, “Reserve Affairs Overview,” 2013, available at <http://ra.defense.gov/about/>.

19 DOD Instruction 1300.19, as of March 2014, 42.

20 Thirty extra military personnel appropriation (MPA) days for each of the nearly 1,400 part-time positions with a $200 per MPA day payroll (an average of O-4, O-5, and O-6 pay) plus retirement accruals.

21 Personal communication with the Joint Staff J1.

22 Vincent C. Bowhers, “Manage or Educate: Fulfilling the Purpose of Joint Professional Military Education,” Joint Force Quarterly 67 (4th Quarter 2012), 26, available at <www.dtic.mil/doctrine/jfq/jfq-67.pdf>; Scott A. Carpenter, “The Joint Officer: A Professional Specialist,” Joint Force Quarterly 63 (4th Quarter 2011), 125, available at <www.dtic.mil/doctrine/jfq/jfq-63.pdf>; Bob Feidler, “Professional Military Education: Is its Evolution in Step with Changing Conditions?” The Officer (July–August 2012), 44, available at <http://d27vj430nutdmd.cloudfront.net/22271/117437/117437.1.pdf>; Robert P. Kozloski, “Building the Purple Ford: An Affordable Approach to Jointness,” Naval War College Review (Autumn 2012), 41, available at <www.usnwc.edu/getattachment/05f44720-70ce-4e7d-be2b-6cc189fc719f/Building-the-Purple-Ford—An-Affordable-Approach-t.aspx>.

23 Personal communication with Jerome M. Lynes, the Joint Staff J7 Deputy Director for Joint Education and Doctrine, and John J. Roesner, Joint Education Advisor.

24 Advanced JPME can be traced to a 1997 initiative by ASD/RA Deborah R. Lee that resulted in a pilot program in 2001, and it predates improvements in distance learning, the post-9/11 era of AC/RC integration, and the future implications of an operational Reserve. See Dayton S. Pickett, David A. Smith, and Elizabeth B. Dial, “Joint Professional Military Education for Reserve Component Officers: A Review of the Need for JPME for RC Officers Assigned to Joint Organizations,” Logistics Management Institute (November 1998), available at <www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?Location=U2&doc=GetTRDoc.pdf&AD=ADA357506>.

25 Title 10 U.S.C. 107 §§ 2154 and 2156.

26 Commission on the National Guard and Reserves: Transforming the National Guard and Reserves into a 21st-Century Operational Force, Final Report to Congress and the Secretary of Defense (Washington, DC: DOD, January 31, 2008), 142, available at <http://cgsc.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/ref/collection/p4013coll11/id/1655>.

27 Olivo; Bob Feidler and Scott A. Sauter, “JPME Overhaul: Reserve Component Members Should Have Equal Access to Reach Level III Status,” The Officer (March–April 2012), 38, available at <http://d27vj430nutdmd.cloudfront.net/22271/104530/104530.1.pdf>; Scott A. Sauter, “JPME Integration Acknowledges Value of Guard and Reserve,” The Officer (March–April 2012), 42, available at <http://d27vj430nutdmd.cloudfront.net/22271/104530/104530.1.pdf>. Reserve Forces Policy Board Annual Reports from 2003 to 2007 are available at <http://ra.defense.gov/rfpb/reports/>; Quadrennial Defense Review Report; VCJCS and ASD/RA, Comprehensive Review, 24.

28 Martin E. Dempsey, “Mount Up and Move Out,” Joint Force Quarterly 72 (1st Quarter 2014), 4.

29 Quadrennial Defense Review Report (Washington, DC: DOD, 2006), available at <www.defense.gov/qdr/report/Report20060203.pdf>.

30 This is known as “boundary-spanning” in leadership development arenas; see Richard L. Daft, Organizational Theory and Design, 3rd ed. (New York: West Publishing Co., 1989), and the Center for Creative Leadership’s White Paper, available at <www.ccl.org/leadership/pdf/research/BoundarySpanningLeadership.pdf>. See also the Army’s Teams of Leaders approach used in U.S. European Command, available at <http://usacac.army.mil/cac2/AOKM/ToL.asp>.

31 Capstone Concept for Joint Operations: Joint Force 2020 (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, September 2012), available at <www.jcs.mil//content/ files/2012-09/092812122654_CCJO_JF2020_ FINAL.pdf>.