ABSTRACT

China has the technology, know-how, and capital to exploit Afghanistan's mineral resources and capitalize on its location, which could make it a transportation hub; concurrently, Beijing sees the risks of dealing with a country with corruption at all levels and with the further problems of primitive infrastructure, low education and expertise levels, potentially hostile neighbors, scarcity of water, and forbidding terrain. Afghan analysts themselves see the need to build economic and social stability as trumping other security and military needs. Meantime, U.S. and NATO forces are spending trillions to prepare Afghanistan for China and other countries to reap the benefits. This outcome, while controversial, may be the easiest way for Kabul to rise above its disorder and poverty.

As the 2014 withdrawal of U.S. and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) troops draws closer, the question on many minds is what will become of Afghanistan. Will the country slip back into its usual pattern of power struggles, be taken over by the Taliban, or continue to develop into a global economic player?

In June 2010, reports estimated that there are more than $1 trillion in mineral deposits within the borders of Afghanistan. While this may seem promising, there are many economic, logistical, cultural, military, and geopolitical issues to resolve before beginning the exploitation of those natural resources to help lift the country out of its current state. Export of strategic minerals could offer Afghanistan an opportunity to become a successful player in the global economy, but success is contingent on the creation and maintenance of a viable, centrally controlled police and military force, and on the central government’s ability to hold sway over its interaction with bilateral partners, as well as domestic tribes, through the years to come. A number of possible outcomes could occur based on the dynamics of the internal makeup, tribes and their influence within the country, and ties outside the country.

As foreign troops, equipment, and donation amounts dwindle over the coming years, Afghanistan will be drawn into the orbit of its immediate neighbors regarding influence and future direction. In both regional and global competition, the Chinese are ahead in the areas of direct investment and long-term outlook in the Afghan natural resources sector. Although this prospect may initially be distasteful to those who have shed blood and treasure over the past decade to create a viable state within Afghanistan, it may be the best way to achieve the endstate those nations strived to establish.

Member of U.S. Geological Survey conducts site survey outside Sukalog, Afghanistan, with Marine security (U.S. Marine Corps/Sarah Furrer)

Amid the Chaos Hides a Pearl

Afghanistan, a country rich in culture and history, lags far behind much of the rest of the world economically, in infrastructure development, and as a socially integrated society. In the 1960s and early 1970s, the Soviets, along with the Afghanistan Geological Survey (AGS), were the first to map the country’s geologic strata in great detail. However, their work was disrupted by the 1979 Soviet invasion, the occupation that followed, and the civil war. During the post-1996 chaos, a small group of Afghan geologists hid the geological reports produced during the 1960s in their homes in an effort to protect them from being destroyed by the Taliban.

The U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in late 2001 ousted the Taliban, and the long process of rebuilding began. Today, as U.S. and NATO forces strive to improve the security situation, the Ministry of Mines (MOM) is trying to kick-start the mining industry by opening up mining opportunities to foreign companies. The goals of the NATO coalition over the period 2001–2012 have generally been:

- destroy al Qaeda and its affiliates residing in Afghanistan and defeat or neutralize those elements posing a threat to the country and its neighbors

- train, equip, and enable a self-sustaining Afghan National Security Force (ANSF) that can protect the country from external and homegrown threats

- help create the conditions for economic recovery and development by supporting those Afghan institutions that lend assistance to this effort.1

For any major investment and development projects to succeed, the NATO-led mission must attain its goals in concord with the central government in Kabul. Despite continuous criticism, it could be reasonably argued that the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) has been achieving those goals thus far. The al Qaeda network within Afghanistan has been effectively eliminated (although a Pakistani-based insurgency remains a menace), ANSF is nowadays a well-trained and well-equipped force that has reached its intended strength levels, and the organs of effective management of governmental programs are in place, albeit in some places still weak and/or embryonic. ANSF with its bureaucratic pitfalls and potential for corruption will be the most important organization to rehabilitate and therefore sustain and will be crucial to natural resource exploitation.

Out of the Ashes

Afghans have been mining gemstones such as lapis lazuli and emeralds for centuries. These small operations are archaic at best. Gemstones are mined the old way with pick, shovel, and dynamite. The miners are Afghan migrants who leave their families for half of the year to live in windowless huts in a place called Mine Town and earn up to $10 per day.2 In the snowcapped Panjsher mountains, almost 10,000 feet above sea level, hundreds of untrained miners search for some of the highest quality emeralds in the world.3 These operations have continued uninterrupted even during the fight against the Soviet Union in the 1980s and their profits helped to fund the mujahideen.4 Meanwhile, larger extraction operations arose in cooperation with Moscow. In 1959 the Soviet Union developed a number of oil and natural gas fields and later three uranium mines and some copper mines, but large-scale mineral extraction remained underdeveloped. Afghanistan’s mining industry began its renewal during the new millennium at about the time the AGS began undergoing its post-Taliban renovation. It was then that the hidden geological reports began to reemerge, some even punctured with bullet holes from past battles.

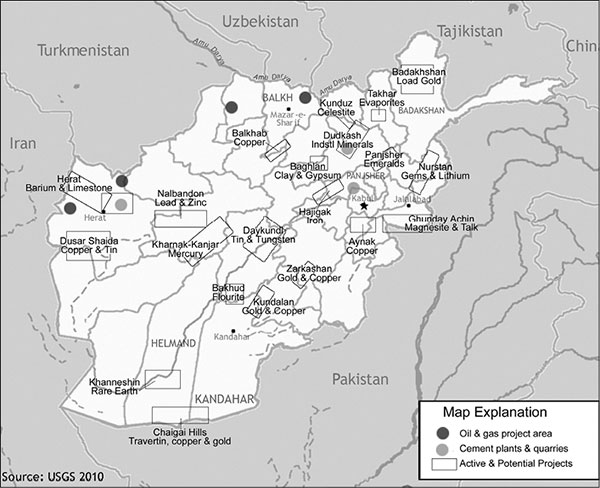

Between 2004 and 2007, scientists from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) joined forces with the AGS to track down existing information about mineral deposits within the country. They gathered information from Afghan, German, Soviet, Polish, Czech, and other sources and combined it to create the Preliminary Assessment of Non-Fuel Mineral Resources of Afghanistan. According to the assessment, the country has an abundance of non-fuel mineral resources such as copper, iron, sulfur, bauxite, lithium, and rare earth elements. The USGS determined that 24 high-priority areas required further analysis, believing that within these areas are world-class deposits of strategic minerals. In June 2006 the revitalized AGS reoccupied the newly renovated AGS building, equipped to access and study old and new data.5

In 2009 the USGS began working with the Department of Defense Task Force for Business and Stability Operations (TFBSO) using both airborne and satellite geophysics and remote sensing to gather new information to validate older information. The data gathered during phase one and subsequent work with TFBSO were used to create high-quality thematic maps and images that were put into a Geographic Information System framework.

The Race for Strategic Minerals

In early December 2011, Afghanistan began a licensing program to allow foreign companies to bid on various exploration and development programs throughout the country.6 According to Jack Medlin, a geologist with USGS international programs, “If someone would go in and rehabilitate and restart the existing oil and gas fields, and if someone would go in and do exploratory drilling, in five to seven years there would likely be enough energy in Afghanistan, especially if you add in the coal, to meet the energy needs of the country. However, it simply has been slow to develop (the extractive industry) or restart.”7

To date, offering huge incentives, Chinese companies have been the top natural resource investors in Afghanistan. Beijing has bought the rights to two major projects: the oil and natural gas blocks in Amu Darya and the Aynak copper deposit. In 2011 the state-owned China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) reached an agreement with Kabul on the final terms of a deal to develop the Kashari, Bazarkhami, and Zamarudsay oil fields in the Amu Darya basin. According to Jalil Jumriany, an Afghan MOM official, for the first 2 years CNPC investment will be $200–300 million. As part of the deal, CNPC agreed to pay a 15 percent royalty on oil and a corporate tax rate of 30 percent to work in the country.8 In addition, CNPC will give up to 70 percent of its profit to the government with the project expected to bring almost $5 billion to Afghanistan within 10 years. Jumriany added that the oil field development project will be run by a 75/25 joint venture between CNPC and local investors and could create up to 7,000 jobs for locals. CNPC also plans to build an oil refinery within 3 years, which would be the country’s first.

Despite the dilapidated state of the infrastructure and a relatively minuscule industrial base, Afghanistan’s domestic requirement for petroleum—for transportation, housing needs, and electric power generation—is estimated at 20,000 to 40,000 barrels per day. Due to the absence of domestic production, the country must import all of its petroleum products. Projects such as the Amu Darya oil field and CNPC refinery will alleviate domestic demand and consumption needs.

In 2007 Afghanistan and the Metallurgical Corporation of China (MCC) signed the largest extraction contract between the host country and a foreign competitor. The $3.5 billion project is a 30-year lease to develop the Aynak copper mine, located 15 miles south of Kabul in Logar Province.9 The mine has an estimated 11 million tons of copper, according to surveys in the 1960s.10 Minister of Mines Mohammad Ibrahim Adel expects the mine to bring the government $400 million annually in fees and taxes in addition to an $800 million down payment from the developer. Moreover, China committed to build a railway line, one or two power plants that will drive the mining equipment and supplement the regional power grid, and a village for workers complete with schools, clinics, and roads. The project is expected to create some 5,000 jobs.11

There are numerous other resources as well. Eighty miles west of Kabul in remote mountainous terrain lies the massive Hajigak iron ore deposit, and three mines have already been awarded to the Steel Authority of India, Ltd., a consortium of Indian companies. According to the Afghan MOM, the deposit is worth an estimated $420 billion and could bring in $400 million in government revenue each year while employing 30,000.12 In addition, it is located close to the proposed MCC railroad north of Aynak. To be financially feasible, the deposit will need access to a rail system due to the weight of iron ore and the cost-to-benefit ratio comparison between using trucks versus rail cars. Afghanistan is also home to a massive world-class rare earth deposit. Rare earth elements are critical to hundreds of high-tech applications including key military technologies such as precision-guided weapons and night vision goggles. They are used in lasers, fluorescents, magnets, fiber optic communications, hydrogen energy storage, and superconducting materials.13 China currently produces over 95 percent of the world’s rare earth elements, and some experts believe the country will soon become a net importer of rare earths.14

There are an estimated 1 million metric tons of rare earth elements within the Khanneshin carbonatite in Helmand Province and an estimated 1.5 million metric tons in all of southern Afghanistan. The deposits are said to be of similar grade to those found in Mountain Pass, California, and Bayan Obo in China’s Inner Mongolia, two of the world’s top light rare earth deposits.15 The main rare earth deposit in Helmand is located atop rocky volcanic terrain, which currently can only be safely accessed by helicopter. While the lack of infrastructure and difficult terrain pose a huge challenge to mining and processing these rare earth deposits, a bigger issue is the ongoing security threat. Helmand is notorious for growing poppy and is a hotbed of Taliban activity.16 According to Mulla Muhammad Daoud Muzzamel, deputy governor of Helmand Province, while “foreign occupiers” have established bases in the province, “an absolute majority of these bases have been under complete sieges for the past few years.”17

Helmand Governor Golab Mangal, however, and other sources are touting an overall improvement in the province. For example, according to Andre Hollis, a former senior advisor to the counternarcotics minister in Afghanistan, the tide is turning in the cultivation of opium poppy. Between 2007 and 2011, production decreased 38 percent. Hollis attributes the drop to a British-run program called the Food Zone. In this program, Afghan farmers are provided fertilizer, seeds, and a scheme to store various crops and transport them to markets outside of Helmand. According to Hollis, Mangal has been a driving force in reducing the opium poppy trade in Helmand. He is credited with taking steps to eradicate the crop, such as ordering the arrests of some family heads of households involved in the trade. The opium trade is a major source of funding for the Taliban; therefore, as Senator Dianne Feinstein pointed out, replanting opium fields with legitimate crops “can ultimately help to cut off financing to the Taliban . . . [and] will help to achieve the dual goal of strengthening Afghanistan’s economy while weakening the Taliban.”18

In addition to programs such as the Food Zone, it is conceivable that the successful mining of the Khanneshin carbonatite rare earths could also contribute to improving Afghanistan’s economy, cutting off financing to the Taliban through job creation and the building of local infrastructure. Of course, the security environment has to improve dramatically first. While Afghan security forces are taking a more active role in leading stability operations in Helmand, their performance is inconsistent, being mainly determined by the caliber of individual leaders. The attainment of a stable environment in the province is still tenuous at best. Once the security situation does improve, it could take over 10 years to put in place all the infrastructure and logistics necessary to make such an extraction venture work. Even then, local expertise is virtually nonexistent and Afghanistan would still have to rely on foreign expertise and backing.

While mining rare earth elements might be simple enough, processing them is another story. They cannot be treated like emeralds or lapis lazuli; they must be separated through complex, multistep processes involving a variety of often-hazardous chemicals and acids. Then the ore has to be transported to another country that is willing to pay the high cost of shipping and processing. China’s proximity and ties to the country and its expertise would make it an ideal candidate to direct the development of Afghanistan’s rare earth elements industry.

China: Influence, Soft Power, and the Competitive Edge

Afghanistan has signed various long-term strategic/cooperation agreements with at least seven countries besides China: Australia, France, Germany, India, Italy, the United Kingdom, and the United States. However, the most effective strategic partnership in the long term would likely be with China.19Beijing seeks both mid- and long-term economic benefits from its growing investment in Afghanistan and hopes to decrease the potential for Islamic extremism born out of Afghan poverty. Since September 2001, China has taken various steps to strengthen its relationship with Afghanistan. In 2004 it relieved the Afghan government of all matured debts, and in 2006, during a visit by the president of Afghanistan, both countries signed the Treaty of China-Afghanistan Friendship, Cooperation, and Good Neighborly Relations. In March 2010 the president of Afghanistan paid another visit during which both parties signed a number of agreements on trade and economic development. China also applied a zero-tariff status to some products originating from Afghanistan.20

China’s approach is different from that of the United States. According to Chinese author Wang Jian, Washington attempts to defeat the Taliban through large-scale attacks. As the fighting spreads, “Taliban counterattacks are bound to intensify,” and “it will be impossible for Afghanistan’s future security situation to break free from arduous difficulties. The present situation has exacerbated the investment environment in Afghanistan, lowered the investment rate, and increased operational risks; security problems are becoming the biggest risk in mining investment.”21 Clearly, Wang’s opinion ignores the billions spent by the United States on investments to alleviate poverty and rebuild infrastructure, not to mention its efforts against Taliban extremism, one of the pillars of China’s professed fight against the “three-isms”—terrorism, extremism, and separatism.

The most marked ideological difference between Chinese and U.S. relations with other nations is best outlined in a 2008 report by the Congressional Research Service, which states that China is known to offer other nations opportunities in foreign investment and aid projects in a “win-win” situation. While these countries provide China with natural resources or a trade market in which to operate, China provides its aid under a policy of “noninterference” in other nations’ political and economic realms without concern for corruption or any such unethical business practices as might exist.22 That is, China turns its head away from ethics and directs its attention toward self-gain. On the other hand, the “the U.S. emphasis on shared democratic values, considered to be a pillar of American soft power, can be perceived in other countries as an obstacle to arriving at solutions to international problems.”23 Ethics and political correctness matter in the United States whether it is a realistic line of attack or not and whether the host country accepts the principle or not. The bottom line is that China and the United States do not adhere to the same moral and legal practices.

The Spread of Corruption

For any legitimate enterprise to flourish and for the creation of a civic and commercial system to operate normally, transparent and trustworthy institutions must be in place. As the withdrawal of U.S. and NATO troops draws nearer, corruption is becoming a major issue in Afghanistan. According to social activist Shafiq Hamdam, corruption “feeds the unrest” and “feeds the insurgency.”24 Transparency International’s “Corruption Perceptions Index 2011” ranks Afghanistan as the fourth most corrupt country in the world after Somalia, North Korea, and Myanmar.25 According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Afghan citizens now pay twice the amount for bribes they paid 2 years ago. Transparency International estimates that the current level of $158 per bribe is equivalent to 37 percent of the average Afghan’s annual income. Polls show that Afghans rank corruption as their top concern, over the Taliban, terrorism, or the economy.26

Some claim that this corruption probably has already filtered down into the minerals industry. For example, MCC was accused of winning its contract for the Aynak copper mine through a $30 million bribe paid to Mohammad Ibrahim Adel. Without “reliable evidence” and documents, however, Afghanistan’s High Office of Oversight and Anti-Corruption refuses to investigate the allegations. Some observers have dubbed the mineral wealth in the country the “blood diamond of Afghanistan.” Without adequate transparency and with the government’s rampant corruption, Afghanistan’s natural resources could easily be used to fuel further insurgencies or their revenues could end up in illegal coffers. Indeed, whoever controls the minerals has the opportunity to control the war.

One article described corruption in Afghanistan as daunting with 30 to 50 percent of the economy consisting of the illicit opium trade, which in turn fuels criminal and insurgent elements. The report further stated that “recent presidential and parliamentary elections were characterized by a high incidence of electoral pay-offs and fraud. There was also the scandal at the Bank of Kabul, replete with phony loans to the Afghan elite . . . and billions in U.S. aid funds, which have been misappropriated, worsening corruption despite belated attempts by U.S. officials to track expenditures more carefully.”27 The spread of corruption can be problematic in that it weakens the rule of law, debilitates the judicial and political systems, and causes citizens to lose faith in their government officials.

In October 2010, in an effort to fight corruption, the Afghan government passed a law that would allow the establishment of special tribunals to investigate suspected senior officials.28 While measures are being taken to fix the problem, the troop withdrawal is quickly approaching and only time will tell whether corruption will be more contained after U.S. and NATO forces leave. Thus the question may not be whether corruption will remain prevalent in Afghanistan, but rather who is best apt to handle the ubiquitous corruption when the finger-waggers and nay-sayers are gone.

Other Hurdles to Overcome

While Afghanistan is plagued with security and moral issues that could delay or obstruct its success in the minerals industry, there are a host of other hurdles. Because Afghanistan is landlocked, it depends on neighboring countries to export its mineral goods to world markets. Therefore, it is critical to the mining industry to maintain good relations with its neighbors to diversify its outlets and remain flexible to market requirements. In that regard, roads and railway networks are crucial to any future export-based economic growth. Afghanistan’s rugged terrain, remote locations, and extreme weather conditions make building any kind of transportation infrastructure more costly and challenging. Security concerns such as ongoing insurgency activity, which is more prevalent in the south, can also increase costs for shippers with added security and insurance premiums. Afghanistan runs the risk of having its infrastructure destroyed by insurgent groups.

Building a railway system is the simplest and most economical option for shipping minerals, but there is the problem of choosing a track gauge (distance between the inside edges of the rails that make up the track). According to Piers Connor, an independent consultant on global railway operations, the countries surrounding Afghanistan all have different gauges—a legacy from the days of colonial expansion.29 Before any track is laid, Afghanistan has to decide which gauges to use, or backers must be prepared to take costly steps to overcome the differences.

In June 2012 engineers from the China Railway Company began researching the technical aspects of building the railway that would connect the Aynak copper mine to Uzbekistan as part of China’s deal to extract copper. The cost is estimated at $4 billion.30 The MOM in mid-2011 publicly proposed a viable alternative rail route running west to Iran, then along the Zaranj-Delaram Highway to the Iranian port of Chabahar. In late 2011, India appeared to be planning to construct this railway, allowing for additional export routes rather than relying on MCC’s eastern rail route to Torkham. This is, above all, an effort by India to develop further alternative routes out of Afghanistan that do not cross Pakistan.

Access to water is another hurdle. Water is used throughout the mining process, from extracting the mineral to milling, washing, and flotation (bringing the target minerals to the surface after crushing and milling them). Huge amounts of water are also used for secondary oil recovery (water is injected into an existing oil reservoir to build up pressure, which allows more oil to be recovered). With water in short supply and the population depending on agriculture, farmers have been digging deeper wells, using pumps to reach scarce water to irrigate their lands. The search for obtainable water could create competition between the mining industry and other industries for supplies. Added to that, some observers fear the mining process could damage the environment. Afghanistan has little history of environmental protection, which has some observers wondering if the country is capable of engaging in mining and development activities responsibly.31 Projects that prove damaging to the environment could easily prompt citizen protests and unrest, which would be detrimental to the country’s leadership.

Finally, lack of technical expertise in all areas related to the mining and developing of its own resources makes the country heavily dependent on foreign assistance. Technical expertise is needed to achieve each step, from building up infrastructure, to mining and processing minerals, to distributing them. China, through its vast resources, is ideally suited to provide the technical expertise needed for success and has much to offer through its ever-growing global experience in the mining industry.

Conclusions

Afghanistan’s economic issue is complex. While its vast mineral wealth would seem to offer an ideal solution to its hardships by creating jobs and trade, its infrastructure, regional vulnerability to neighbors and outside actors, education and expertise levels, environmental fears, rugged terrain, and lack of water are formidable barriers. Even smaller issues, such as differences in track gauges, can throw a monkey wrench into the equation. Yet these obstacles may not be impossible to overcome.

The consensus among Afghanistan’s own analysts is that, more important than focusing on security and building up the country’s military forces, Kabul needs to implement steps to build stability in the economic and social structures. Rohullah Ahmadzai, head of the media section of the Investment Support Administration in Afghanistan, stated that security can now be more effectively strengthened if more efforts go toward social and economic investment.32 He pointed out that since mid-2011, when discussions about the possible departure of the International Security Assistance Force began to surface, there have been increased anxieties regarding the economy, especially in the private sector. Not only are Afghan investors wondering whether private investment opportunities will continue to exist; foreign investors are too.33 It is a vicious cycle. Political and security stability is essential to investment in the mining industry. Equally, however, social and infrastructure investment must promote stability in the region. Without one the other cannot exist.

The Sino-Afghan relationship seems to be a win-win situation. China has the technology, expertise, money, and political will to make a difference. The Chinese are taking a major risk putting so much into a country that ranks so poorly in the corruption index. However, while the risks are high in Afghanistan, there are many potential benefits to China. For one thing, Beijing is in desperate need of natural resources to help develop its economy; moreover, Afghanistan is ideally located to serve as a central transportation hub. Some observers might question the soundness of U.S. and NATO forces spending trillions just to pull out and have countries such as China come in and reap the profits gained through U.S. and NATO blood and money. Unfortunately, Chinese access to Afghanistan minerals is probably the most likely outcome and could prove to be the easiest solution.

China understands the regional stakes involved with Afghanistan’s stability. It has its own Islamic insurgency in the western part of the country. Continued instability in Afghanistan can only exacerbate those risks. Accordingly, China is keeping a watchful eye on Afghan National Security Force development. Beijing’s security-related bilateral engagement with Kabul, although modest, is probably aimed at increasing its influence and bolstering security for its investments. China hosts a small number of ANSF officers—around 60 per year—for training and has supplied small quantities of assistance for security and law enforcement agencies. It has also provided the ANSF with counterterrorism and mine-clearing training and is suspected of agreeing to fund the training and equipping of ANSF personnel responsible for guarding Chinese mining and infrastructure projects.

It is impossible to project in what direction Afghanistan will head and how its mineral wealth might or might not pull the country out of its current poverty and chaos. For now, however, the odds seem stacked against the country, and if there is economic success in Afghanistan’s future, it will take years or decades to achieve even with China’s aid. JFQ

Notes

- Gleaned from official North Atlantic Treaty Organization and ISAF documents. Each year, commander and election cycles seem to bring incremental changes to the official “Why are we in Afghanistan?” question. Thus this is a summary of numerous versions of official documents.

- Soraya Sarhaddi Nelson, “Tapping into Afghanistan’s Wealth of Gems,” National Public Radio, September 7, 2007.

- “Afghanistan’s Emerald Miners,” The Guardian, May 4, 2009, available at <www.youtube.com/watch?v=LaK0A082G1I&feature=related>.

- Lester Grau, telephone interview by author, July 24, 2012. Dr. Grau is a Senior Research Analyst at the U.S. Army’s Foreign Military Studies Office who has long specialized in Afghanistan.

- Kathryn Hansen, “Afghanistan’s Mineral Resources Laid Bare,” Earth Magazine, December 2011, available at <www.earthmagazine.org/article/afghanistans-mineral-resources-laid-bare>.

- Robert Cutler, “Kabul Starts Race for Tenders on Afghan Resources,” Asia Times Online, December 14, 2011.

- Jack Medlin, telephone interview by author, January 20, 2012.

- Daily ISAF Open Source Digest, December 28, 2011.

- Slobodan Lekic, “Afghanistan, China Sign First Oil Contract,” Associated Press, December 28, 2011, available at <http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/money/industries/energy/story/2011-12-28/china-afghanistan-oil-contract/52251500/1>.

- Sardar Ahmad, “Afghanistan Sitting on a Gold Mine,” Agence France-Presse, February 21, 2008.

- Ibid.

- Sarah Simpson, “Afghanistan’s Buried Riches,” Inside Afghanistan, September 22, 2011, available at <www.insideafghanistan.org/>.

- Cindy Hurst, “China’s Ace in the Hole: Rare Earth Elements,” Joint Force Quarterly 59 (4th Quarter 2010); and Li Zhonghua, Zhang Weiping, and Liu Jiaxiang, “Application and Development Trends of Rare Earth Materials in Modern Military Technology,” Hunan Rare-Earth Materials Research Academy, China, April 16, 2006.

- David Stanway, “China Reshapes Role in Rare Earths, Could Be Importer by 2014,” Reuters, July 10, 2012.

- “USGS Releases Resource Estimate for Afghanistan Rare Earth Prospect,” United States Geological Survey Newsroom, September 9, 2011, available at <www.usgs.gov/newsroom/article.asp?ID=2936>.

- “Security to Remain Daunting Challenge for Afghan Government in 2012,” Xinhua News Agency, January 2, 2012.

- “Interview with Deputy Governor Mulla Muhammad Daoud Muzzamel,” Taliban Voice of Jihad Online (Pashtu), March 22, 2012, available at <www.alemara1.net>.

- Rowan Scarborough, “Doubts of Victory Surface in War on Afghan Poppy Crops,” Washington Times, April 22, 2012.

- “Radio Faryad Talk Show Discusses Strategic Pacts with the United States and China,” Radio Faryad (Dari), May 30, 2012.

- Wang Jian, “Brief Analysis on the Environment of Investment in the Mining Industry in Afghanistan,” Natural Resource Economics of China Journal(Chinese), November 2011, 43–44.

- Ibid.

- Thomas Lum et al., Comparing Global Influence: China’s and U.S. Diplomacy, Foreign Aid, Trade, and Investment in the Developing World, RL34620 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, August 15, 2008).

- Ibid.

- Allen Pizzey, “Corruption Is Afghanistan’s Biggest Problem as Foreign Forces Prepare to Leave,” CBS Evening News, May 18, 2012.

- Transparency International, “Corruption Perceptions Index 2011,” available at <http://cpi.transparency.org/cpi2011/results/>.

- Maria Gili, “Corruption in Afghanistan: the Status Quo Is Not an Option,” May 22, 2011, available at <http://blog.transparency.org/2011/05/11/corruption-in-afghanistan-the-status-quo-is-not-an-option/>.

- Ben W. Heineman, Jr., “Afghanistan’s Corruptions Imperils Its Future—and American Interests,” The Atlantic, July 23, 2012.

- Wang.

- Russian gauge is measured at 1,520 mm (or 59.843") and 1,524 mm (or 60"), while China and Iran use a standard gauge (1,435 mm), and Pakistan uses the Indian gauge (1,676 mm).

- “Chinese Engineers Arrive in Afghanistan to Plan Railway,” Tolonews.com, June 7, 2012.

- James Risen, “U.S. Identifies Vast Mineral Riches in Afghanistan,” The New York Times, June 13, 2010.

- “Discussion on Economic Concerns After Foreign Troops Withdraw,” Tolonews.com, May 27, 2012.

- Ibid.