Download PDF

Bryce Loidolt is a Senior Research Fellow for Defense Capabilities and Partnerships in the Center for Strategy and Military Power, Institute for National Strategic Studies, at the National Defense University.

A growing chorus of U.S. defense analysts, lawmakers, and military officials has emphasized that the United States lacks the munitions production capacity to meet the demands of the contemporary strategic environment.1 The results of public war games underscore this deficiency, suggesting that in the event of a conflict with China the U.S. military could run out of munitions within weeks.2 Although concerns over the responsiveness of the U.S. defense industrial base to strategic imperatives pre-date Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the extended drawdown of U.S. stocks to support the Ukrainian armed forces have brought these concerns into greater focus.3 As one account describes, “One of the many lessons learned from the ongoing war in Ukraine is the inadequacy of the U.S. defense industrial base to keep pace with high-intensity conflict.”4

Although certainly true, narratives of the U.S. defense industrial base’s inadequate performance during the Ukraine crisis overlook the real—albeit still mixed—progress the United States achieved in boosting some munition production rates from 2022 to 2024.5 During this period, the production rate of certain munitions increased while others stagnated. The reasons behind this variation could imply lessons or models the Department of War (DOW) could employ in future crises to ensure more pronounced munitions surges across the board. For their part, existing studies have tended to focus on either improvements that can be made to improve the industrial base’s baseline performance in a peacetime environment or, alternatively, lessons from World War II for the future mobilization of the U.S. economy to support a protracted conflict.6 The ability of the industrial base to surge— defined as the time-bound increase in production that does not entail the mobilization of the civilian economy—has received less attention.7

This article fills this gap by comparing four munitions that experienced diverging levels of production ramp-ups after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It finds that although the United States was able to quickly and flexibly resource industrial base improvements and put orders on contract after 2022, post-crisis efforts were not responsible for these patterns of increase and stagnation.8 Instead, it was pre-crisis procurement and associated investments that led to this variation. Munitions that the U.S. military Services put on contract prior to the crisis were those that experienced the most pronounced surge during the crisis.

This finding underscores the need for more urgent action on the part of DOW to conceptualize, enhance, and test munitions surge capacity “left of crisis.” It points to the need for greater cross-departmental alignment on and awareness of surge methodologies and triggers, enhancement of U.S. surge instruments, the explicit inclusion of surge into mobilization exercises and war games, and a broader reconsideration of the U.S. portfolio of high-end munitions. DOW must avoid a binary distinction between peacetime “business-as-usual” defense industrial base posture and a comprehensive mobilization of the civilian economy.

This article begins with a brief overview of the U.S. military’s experience with munitions shortages and associated mitigations since World War II. Among the latter is often an effort to accelerate production and deliveries to meet intense demands. It then turns to common barriers the department has encountered in trying to surge, including lack of capacity, obsolescence, long lead time materials and components, and supply chain visibility and bottlenecks. Following this discussion, it evaluates variation across four munitions, tracing this variation back to pre-crisis procurement and investments. It concludes with implications for U.S. defense policy.

Munitions Shortages and Mitigations Since World War II

Munitions shortages are not new for the U.S. military, DOW, or the U.S. defense industrial base. Concerns over the impact of contingencies on U.S. materiel readiness during major crises have indeed been a near constant since the end of World War II. With these concerns has come a push to adopt several mitigations.

At times, the daylight between projected materiel needs and the intensity of combat operations have lowered U.S. readiness levels. U.S. combat operations in Korea strained U.S. supplies of 4.2-inch mortars, hand grenades, and 155mm howitzers.9 Operation Allied Force in Kosovo significantly stressed the U.S. military’s missile inventory, such as conventional air-launched cruise missiles and Tomahawk Land Attack Missiles.10 Operations Enduring Freedom and Inherent Resolve placed a similar strain on U.S. Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) stocks.11

In other cases, the stress to U.S. stocks has not come from direct U.S. participation in combat operations but rather from drawing down U.S. inventories to support an ally or partner. During Operation Nickel Grass in 1973, the U.S. Air Force orchestrated the airlift of 22,305 tons of materiel to help resupply the Israeli armed forces during the Yom Kippur War.12 Much of this materiel, featuring badly-needed F4 fighters, 105mm ammunition, and Maverick missiles, came from U.S. operational inventories.13 Among other impacts on U.S. military readiness, these transfers left one U.S. F4 squadron without aircraft and severely limited the capacity of another.14

No matter the decade or cause, these shortages have frequently been met with a variety of mitigation strategies. The simplest of these strategies has been to simply direct combat units to fire fewer rounds. In 1952, the U.S. Army man- dated, for example, that fielded units in Korea ration ammunition to “bridge the gap between the decreasing stockpile and new production.”15 In other instances, the military has sought to convert or alter existing capabilities to serve as substitutes for dwindling stocks of other munitions. Amid munitions shortages experienced during Operation Allied Force, for example, the then–Department of Defense (DOD) altered nuclear-tipped air-launched cruise missiles to meet the conflict’s munition demands.16 During Operations Inherent Resolve and Enduring Freedom, DOD also managed risk by shifting munitions across combatant commands or Services to meet pressing operational requirements.17

In tandem with or in lieu of these mitigations, DOD/DOW has also often attempted to ramp up production of key munitions to meet increased demand. During Operation Enduring Freedom, for instance, the United States sought to triple the production rate of JDAMs.18 Operation Inherent Resolve similarly led the U.S. Air Force to again temporarily boost production of these munitions as well as small-diameter bombs and air-ground munitions.19

Barriers to Surge

The ability of the U.S. industrial base to rapidly increase the production of munitions has long been constrained by several well-documented obstacles. A readout of Proud Saber 83, a 1982 DOD exercise designed to test existing mobilization procedures, is instructive in this regard. Following two national-level command post exercises of mobilization plans, Proud Saber 83 led DOD to conclude that a “six-month industrial surge would yield only a negligible increase in production. Surge capability is limited by the need for long-lead-time components, shortages of specialized equipment, and sole source production of pacing components by subcontractors.”20

The post–Cold War consolidation of the U.S. defense industry only made matters worse, incentivizing industry to slash excess industrial capacity and ultimately yielding a munitions industrial base that was not fit to surge during a crisis.21 Component obsolescence, supply chain vulnerabilities and visibility, and capacity shortages are indeed reinforced by these structural conditions.

The issue of obsolescence has long imposed a rather stringent upper bound on the speed and scale of U.S. missile production. Obsolescence occurs when the original manufacturer or supplier of an item or raw material ceases production or is no longer in business. It can also occur when those items are so outdated so as to longer be useful.22 Microelectronics are frequently the culprit due in large part to the turn to commercial-off-the-shelf components, which have a much shorter lifespan than the average DOW system life cycle.23 In practice, a key mitigation for U.S. munitions manufacturers has been to pursue expensive lifetime buys of soon-to-be obsolescent items or requalification and redesign efforts to manufacture a new replacement part. The former is expensive and not feasible when those items have a limited shelf life, and the latter is time-consuming and costly, making it an unattractive option when needing to surge in a crisis.

A related challenge is single or sole source suppliers for key items or materials. One study from the 2010s of 35 key munitions found that 98 percent of the critical components in the second and third tiers of these munitions’ supply chain were single or sole source.24 In some instances, these items are defense-specific, and accordingly their production rates are tied directly to volatile demand signals from DOW. The solid rocket motor industry, for instance, has consolidated over decades, leaving few options available to the multitude of the munitions that use them for propulsion.25 When these single- or sole-source suppliers encounter unanticipated production challenges, no longer produce a part, or otherwise choose to restrict supply of key materials, all production lines reliant on it will grind to a halt.

Recognizing these supply chain vulnerabilities can itself be a challenge given the sheer complexity of munitions production and the reliance on subtier suppliers. Defense policymakers and acquisition professionals frequently have a limited baseline visibility into munition supply chains, portions of which may reside abroad.26 Accordingly, the department relies on deep dive assessments designed in part or in full to map and illuminate interdependencies and capacity challenges in these lower production tiers.27

Shortages in production capacity, exacerbated by an aging workforce and antiquated manufacturing and testing tools, further constrain the munition industrial base. Munitions production is a complex endeavor, often requiring uniquely skilled personnel and, in some cases, requiring such precise modifications that “touch,” hand-on labor is the preferred approach. Employees with these specialized skills are in short supply.28 The specialized tools and testing equipment needed to make sure munitions work properly take a long time to build and are expensive to keep ready when production is dormant.29

A cyclical “boom and bust” munitions procurement pattern by the U.S. military Services reinforces these challenges, rendering industry reluctant to invest in excess or even baseline production capacity without a concrete demand signal.30 Fluctuations in defense contracts thus increase the risk that individual companies will lose production work and be unable to retain their workers on production lines or maintain and upgrade their equipment. The result is a limited ability for the munitions base to ramp up production when a crisis hits and magazine depth plummets.

These challenges imply that surging munitions production during a crisis would be a considerable undertaking. As alluded above, though, some munitions provided to Ukraine witnessed production increases while others did not.

Security Assistance to Ukraine and the Surge Imperative

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, U.S. security assistance to Ukraine has come through two channels. The first channel, the Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative, was authorized in 2015 to provide training, military assistance and other support to the Ukrainian armed forces. This funding stream allows the United States to procure military capabilities from the defense industry to, in turn, provide them to Ukraine. A complementary stream of support has come through Presidential Drawdown Authority (PDA), which authorizes the President to provide materiel support to a U.S. ally or partner from existing U.S. military stock.31 Both initiatives have necessitated production ramp ups, whether to more quickly meet Ukraine’s operational requirements or replenish U.S. military stocks to offset any degradation in U.S. military readiness imposed by PDA transfers—or both.

Early in the crisis, DOD leaders were able to leverage preexisting and new authorities, resource streams, and processes to reduce administrative lead times and ensure ample funding for industrial base improvements. From 2022 to 2024, Congress authorized five tranches of Ukraine supplemental funding, a portion of which was dedicated to DOD procurement accounts to replenish munitions and boost production capacity.32 The 2023 National Defense Authorization Act further authorized flexible acquisition authorities for Ukraine-related contracts, to include the use of other-than-competitive procedures, and DOD made extensive use of undefinitized contracting actions and indefinite delivery/indefinite quantity contracts to expedite acquisition timelines as well.33 Moreover, in October 2022, the White House issued a Presidential Determination, allowing the President to directly fund the acceleration and expansion of defense production capacity to support Ukraine using Defense Production Act Title III funds.34

With these funds and authorities came additional organizational bodies and processes to manage them. In 2022, DOD reestablished what had previously been known as the Munitions War Rooms—now renamed the Munitions Industrial Base Deep Dive effort and eventually institutionalized as the Joint Production Acceleration Cell in March 2023—to assess production constraints and direct funds to mitigate them.35 It also established a Senior Integration Group–Ukraine as a higher forum to quickly align requirements, contracts, and funding.36

The apparent results of efforts to boost production were outlined in a September 2024 DOD press release highlighting the industrial base achievements of the United States, its allies, and partners. Noting that the United States had invested $5.3 billion to “expand domestic production capacity” of several munitions, the release touted production increases across a variety of munitions. These munitions run the gamut of the relatively simple 155mm projectile as well as the more complex Patriot Advanced Capability–3 Missile Segment Enhancement (PAC-3 MSE), the Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System (GMLRS), the AIM-9X “Sidewinder,” and Javelin missiles (see figure 1).37

Figure 1. Munitions Production Increases, 2022–2024

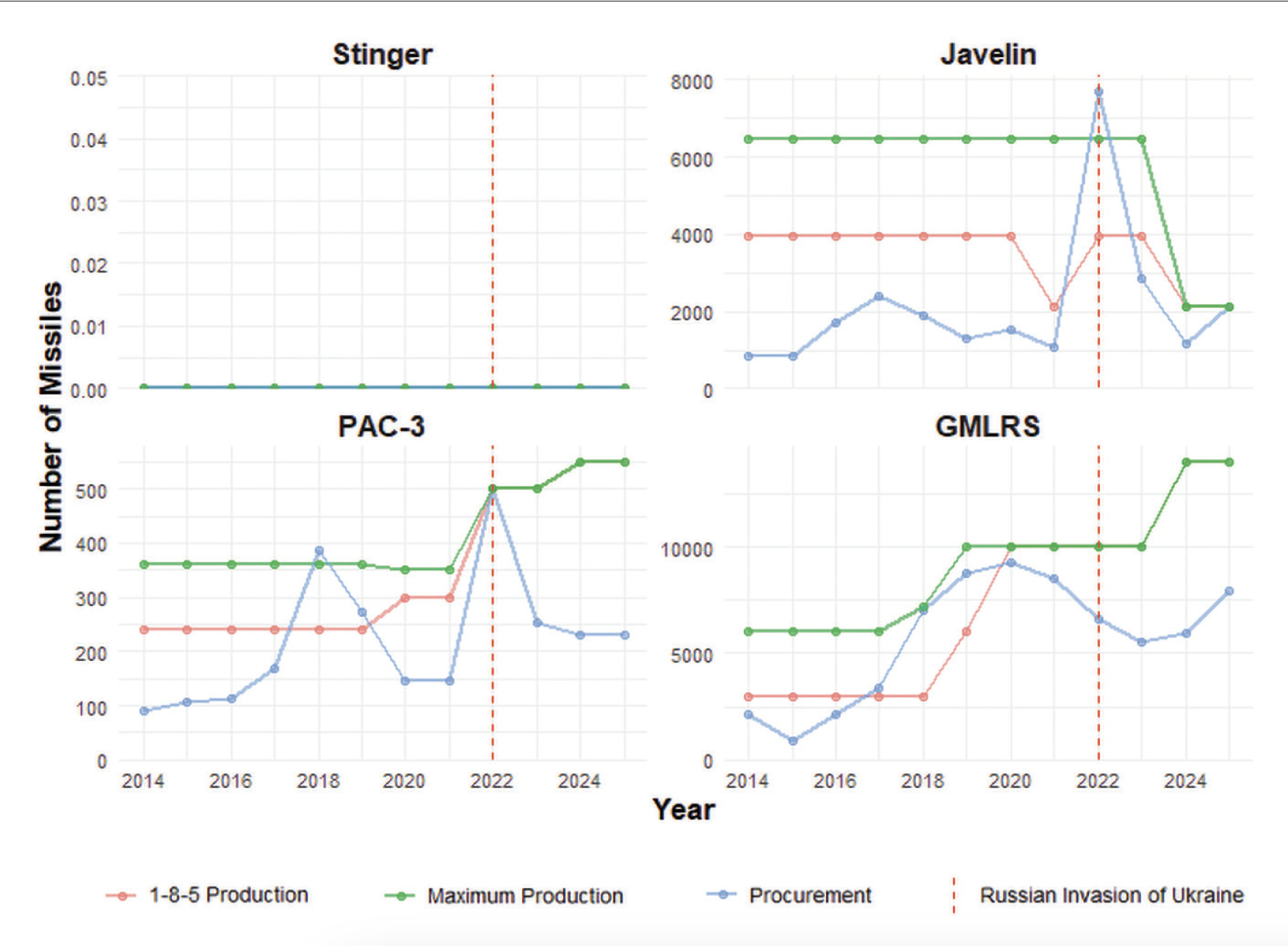

Figure 2. Procurement Quantity and Production Rates

By emphasizing them as “significant achievements” and juxtaposing them with crisis-era investments, the press release strongly implies that these investments and activities contributed to these impressive increases in production. Yet even if this were the case, the patterns reflected in figure 1 are neither intuitive nor complete. For one, the rate increases do not readily correlate with munition complexity. The robust boost in the production of the unguided World War II–era 155mm projectile may be an unsurprising if challenging milestone. What is surprising, though, is the doubling of the much more modern (and chip-laden) (PAC-3 MSE) air defense munition production rate. And the production of Javelin missiles, which are less advanced than the PAC-3, witnessed far more modest increases.

Just as important is the need to consider munitions where DOW may have attempted to surge but where production stagnated. Such cases, of course, would naturally be absent from a public-facing press release. But including these cases in a broader analysis is necessary to make credible claims about the sources of surge success and failure during the crisis, and, in turn, to help DOW improve surge capacity during future contingencies.

Case Study Analysis

This study seeks to uncover why some U.S. munitions witnessed more dra- matic production increases than others during the Ukraine crisis. Its central thesis is that pre-crisis procurement decisions were largely responsible for post-crisis surges. The decision to procure munitions can come with investments in production capacity. So, too, procurement can help keep supply chains flowing and, with effective program management, help illuminate and circumvent bottlenecks and anticipate obsolescence.

To evaluate this explanation, the case study examines procurement patterns and production rates of a cross-section of munitions provided to Ukraine since Russia’s full-scale invasion. These munitions include Stinger, Javelin, GMLRS, and PAC-3 MSE. Each is a guided munition provided to Ukraine prior to 2024. For each munition, U.S. policymakers or defense manufacturers also referenced a desire to accelerate production. These munitions are also managed by the U.S. Army, holding that potential confounding variable constant. Still, the munitions examined in this study are not a random sample and are not perfectly comparable.

Drawing on U.S. Army budgetary and procurement data, figure 2 provides additional clarity and context to claims of post-crisis production increases. It depicts 2002–2024 fluctuations in procurement and production for each munition examined in this study. With respect to the latter, the figure illustrates the maximum production rate, which is the highest production rate possible with current facilities and capacity, and the 1-8-5 Production rate, which is the number of missiles the manufacturer could produce with current capacity working one 8-hour shift, 5 days a week.38 These data imply support for the claim that pre-crisis production patterns were an important determinant of post-crisis surge. Yet additional confidence in this claim requires a more fulsome discussion of each munition, which the subsequent sections provide.

Stinger. First fielded in 1981, the Stinger missile is a man-portable air defense system suitable for targeting low-flying manned and unmanned aircraft. Since announcing the first shipment in early 2022, the United States has provided over 3,000 of these missiles to the Ukrainian armed forces. These missiles allow Ukrainian forces to shoot down low-flying Russian planes, helicopters, and other airborne threats.39

Buoyed by the flexible acquisition authorities referenced above, U.S. contracting personnel moved remarkably fast to procure replacement Stinger missiles to replenish U.S. Army stocks.40 After receiving supplemental funding on May 1, 2022, the department issued an undefinitized contract order to replenish U.S. stocks within 20 days.41 Accordingly, by the end of May 2022, the department had awarded the manufacturer a $624 million contract.42

At the onset of Russia’s invasion, though, the United States had not purchased a Stinger missile in 18 years.43 U.S. stocks were full and maintained through a service life extension program, and the Army was pursuing a modernized replacement.44 The program itself had been started (and stopped) seven times prior to the Ukraine replenishment to fulfill foreign military sales orders.45 Many of the rare and dated components required for this limited production were provided by the foreign customer itself rather than the manufacturer and its subtier suppliers.

The “cold” production line had consequences when trying to ramp production to replenish U.S. stocks in a timely fashion in 2022. A lack of procurement created a situation where a number of missile components in the seeker head were “no longer commercially available” and, accordingly, had to be redesigned before production could resume.46 These obsolescence challenges were compounded by the fact that the workforce with the requisite skills to assemble the missile, which is done by hand, had largely retired.47 Beyond the seeker components, Stinger production was also hampered by limitations in solid rocket motor production.48 As a result, DOD and the manufacturer alike estimated that missiles ordered in May 2022 will not be delivered until at least mid-2026, despite an original estimation that production could resume in 2023.49

Javelin. A man-portable fire and forget antiarmor missile fielded in 1996, Javelin was provided to the Ukrainian armed forces prior to and after Russia’s 2022 invasion. Dubbed “Saint Javelin” by some of its operators, the Javelin was credited at one point in the conflict as boasting a 93-percent kill rate against Russian tanks.50 Claims of effectiveness aside, since 2022 the United States has provided over 10,000 Javelin missiles to Ukraine through PDA transfers.51 Much like Stinger, pre-crisis production inactivity rendered any rapid increase in production particularly difficult. From 2022 to 2024, Javelin production increased by only 14 percent.

The provision of Javelin missiles from U.S. stocks necessitated boosting production to replenish them. Indeed, early in the crisis, the United States was estimated as having donated around one-third of its stock of Javelin missiles to Ukraine, which under the current production rate would take roughly 5 years to replenish.52 In early 2022, the manufacturer thus laid out its objective of doubling Javelin production, noting “it will take a number of months, maybe even a couple years to get there.”53

Much like Stinger, DOD was able to move quickly to obligate funds to meet this objective. Throughout May, the U.S. Army procured over 2,000 Javelin missiles, utilizing both Army and Ukraine supple- mental funds.54 Additional procurement of replenishment Javelins followed, consisting of $311 million for 1,800 Javelins in September 2022 and a 2023 3-year procurement of up to $7 billion worth of Javelin missiles.55 From 2022 to 2024 the United States also invested $78 million of supplemental funding for industrial base improvements to increase production.56

Prior to the Ukraine crisis, Javelin production lines were only minimally active. As the program executive office described in 2022, “Javelin relies on the combined United States Army, other services, and FMS procurements to reach Minimum Sustaining Rate.”57 Javelin’s propulsion system, specifically solid rocket motors, posed a major dif- ficulty. Unlike many other munitions’ components, solid rocket motors lack a broader commercial customer base and are uniquely tied to the demands of defense programs, missiles in particular. The supply chains for solid rocket motors are complex—by one estimate spanning 1,000 lower-tier suppliers for the motors’ raw materials and subcomponents.58 When the maker for Javelin’s propulsion system faced supply chain challenges, it struggled to deliver propulsion systems to meet the accelerated production timeline.59 Javelin further encountered labor shortages and required additional investments in tooling and test equipment, further inhibiting a more meaningful production increase.60 U.S. Army data reflect these challenges. The maximum production rate of Javelin dropped after Russia’s invasion in 2022.

GMLRS. First fired in 2005, GMLRS are indirect precision fires munitions provided to Ukraine in the summer of 2022.61 With their approximately 70km range, GMLRS allowed Ukrainian forces to strike beyond the front lines, accu- rately engaging Russian materiel storage sites and missile launch locations from standoff ranges.62 Unlike Stingers and Javelin, from 2022 to 2024, GMLRS production witnessed a marked—if still constrained—increase, reaching 14,000/ month by 2024, a 40-percent increase from pre-conflict levels.

Specific numbers of GMLRS provided to Ukraine are not publicly available, but similar to both Javelin and Stinger, the United States moved quickly to award contracts to replenish military stocks after announcing the transfers. Congress approved several tranches of Ukraine supplemental funds dedicated to replacing donated GMLRS rockets and expediting production by purchasing long-lead parts.63 The U.S. Army subsequently awarded contract options to replenish U.S. inventories in October and November 2022, and a subsequent 2024 multiyear procurement award gave way to the more ambitious goal of eventually doubling GMLRS production.64

A 40-percent increase in GMLRS production did materialize by 2024. But that boost draws its sources back to pre-conflict procurement. Although demonstrative of the boom-and-bust procurement patterns that often preclude more robust industrial base investments, the U.S. Army and foreign partners had made significant purchases of GMLRS—over 26,000 rockets in total—from 2017 to 2021.65

This pre-crisis procurement likely paved the way for the 2024 production ramp up by allowing program managers and the manufacturer to identify and, where possible, mitigate production and supply chain challenges before they emerged during the crisis. Such mitigations entailed lifetime buys for application-specific integrated circuit chips, which were critical for GMLRS guidance sets, as well as the manufacture of a new modular pod for its propulsion system.66 By 2021, the manufacturer had established and begun building the capacity of a second source solid rocket motor supplier, and the Army acknowledged “known issues that must be resolved [including] obsolescence of certain components within the safe arm fuze, proximity sensor, guidance set, and motor material.”67

Collectively, these initiatives, which stemmed not from crisis-era investments or activities but rather pre-crisis procurement, facilitated the production ramp up in 2024. Even so, achieving the production boost and associated deliveries still encountered unanticipated challenges.

Key among these challenges were shortages in solid rocket motors, described earlier, which kicked off what the manufacturer described as a “broad” and “campaign-like” effort to add another solid rocket motor supplier.68 Indeed, at the end of 2023, the U.S. Army also needed to resume launch pod container production and to refresh the guidance set due to obsolescence.69 And limits on tooling and testing equipment, labor, and shared suppliers persist and will continue to complicate achieving more ambitious production goals in the future.70

PAC-3 MSE. U.S. Army in 2015, the PAC-3 MSE interceptor is the most advanced variant of the Patriot air defense munitions that Ukraine uses to counter Russian aircraft, cruise missiles, and ballistic missile attacks.71 Although the timing and volume of PAC-3 MSE transfers to Ukraine are not publicly available, DOD first announced the transfer of a Patriot battery and “munitions” in December 2022 through PDA and later acknowledged “resequencing hundreds of Patriot and AMRAAM [advanced medium-range air- to-air missile] air defense interceptors” to prioritize transfers to Ukraine.72 Since then and in the context of support to Ukraine, DOD touted an over 100-percent production increase in PAC-3 MSE missiles from 2022 to 2024, implying that at least a portion of Patriot interceptors provided to Ukraine were the MSE variant.73

As was the case with the other munitions examined in this study, DOD was able to quickly obligate funding and exercise contract options. From June to November 2022, the U.S. Army received supplemental funding and exercised production contract options to procure a total of nearly 300 PAC-3 MSE missiles and associated tooling.74 In total, DOD acknowledged spending a total of $755 million in Ukraine supplemental and replenishment funding for PAC-3 MSE– related investments.75

Prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the U.S. military had been actively procuring PAC-3 interceptors. The Army purchased over 1,000 of the MSE variant in particular from 2015 to 2021.76 Ample procurement aside, the program office also adopted a comparatively proactive approach to managing obsolescence, establishing a “product road map” to control the timing of missile redesigns and insert obsolescence risks as a consideration when choosing parts and components.77 Procurement also came with a greater investment in production capacity, such as a 2019 production facility expansion that was completed in late 2022.78

These investments facilitated the impressive production surge after 2022. The manufacturer had planned to increase the annual production rate to 500 missiles a year prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022.79 And after 2022, the PAC-3 production rate continued to climb, reaching 550 missiles earlier than originally projected.80 This milestone was still hard-earned, requiring synchronization across the supply chain, to include rapidly expanding seeker production to meet surging demand and working through rocket motor production issues.81

Implications: Setting the Conditions for Surge Success

The variation in munition production from 2022 to 2024 draws its roots not back to crisis-era policy instruments, resources, or authorities but rather to patterns of procurement and program management that preceded the crisis. This finding is not to say that crisis-era investments will not yield results in the future but that the U.S. munitions industrial base’s performance during the crisis underscores the inability to quickly and uniformly boost production. It also does not suggest that procurement will in and of itself be sufficient for surge success. Nevertheless, the analysis implies four sets of actions and initiatives that DOW should pursue to better prepare the munitions industrial base to surge.

First, DOW needs to develop a common lexicon and methodology—a playbook—to align its munitions surge efforts. An important if seemingly mundane initial step would be establishing an agreed-on definition of what exactly constitutes a production surge. From this definition, DOW should then develop a common understanding of surge instruments and levers that it can use directly, or indirectly encourage industry to use, to boost production.82 DOW and the broader U.S. Government must then come to an agreement on the conditions that should trigger these instruments’ use. This effort should consist of identifying specific indicators and warnings, tripwires, and triggers to make requisite “left of crisis” preparations to facilitate a subsequent production surge.

Second, DOW must work to enhance the collection of authorities, contracting actions, resources, and organizations at its disposal to boost production of key munitions during times of crisis. The reestablishment of a munitions war room, the codification of the Joint Production Acceleration Cell’s roles and responsibilities, advocacy for Congress to renew and fund the Defense Production Act, and Secretary of War Pete Hegseth’s prioritization of revitalizing the defense industrial base are important steps in this regard.83 So, too, are efforts to solidify DOW’s munitions demand signal to industry, including authorization for multiyear munitions procurement and investments in new manufacturing technologies to increase production efficiency and continued scrutiny to ensure the Services do not forego munitions purchases. In conjunction with these efforts, the Secretary of War should direct the inclusion of surge clauses in procurement contracts for select munitions that will be critical to deterring and, if necessary, prevailing in a Taiwan contingency.84 DOW should also seek more flexible authorities for advance procurement of long lead items early to need and in the absence of the related end item.

Third, developing the tools to execute a production surge will be insufficient; DOW must also practice employing these instruments through tabletop exercises and war games that include (and pay for) industry representatives.85 DOW and U.S. Government–wide planning and exercises must pay direct attention to exercising surge capacity both as a stand-alone response to an acute crisis and as a bridge to a full-scale mobilization of the civilian economy. Put simply, tabletop exercises must avoid a binary distinction between peacetime defense industrial behavior and full-scale mobilization of the civilian economy and instead view the two as occurring on opposite ends of a continuum.

Fourth and last, DOW must consider scalable and modular alternatives to supplement, temporarily supplant, and perhaps even replace more exquisite U.S. munitions. Such munitions may certainly have a quality of their own.86 Yet they can also serve as a convenient stopgap for high-end munitions as production ramps up.

The Ukraine crisis has demonstrated that absent pre-crisis preparation, a swift post-crisis surge in U.S. munitions production cannot be guaranteed. The impressive production increases achieved for some munitions were indeed a function of procurement and investment decisions made prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Mobilization planning will not be sufficient. Senior defense and military leaders must begin preparing for the next crisis now by setting the conditions for pronounced production surges in the future. JFQ

Notes

1 James W. Kilby, “Statement for the Record: On the Readiness of the United States Navy,” Subcommittee on Readiness and Management Support, U.S. Senate, March 12, 2015, https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/statement_of_admiral_james_wkilby1.pdf; Reforming Defense Acquisition to Deliver Capability at the Speed of Relevance: Hearing Before the House Armed Services Comm., 119th Cong. (July 23, 2025), https://www.congress.gov/event/119th-congress/house-event/118465; Seth G. Jones, Empty Bins in a Wartime Environment: The Challenge to the U.S. Defense Industrial Base (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2023), https://www.csis.org/analysis/empty-bins-wartime-environment-challenge-us-defense-industrial-base; Becca Wasser and Philip Sheers, From Production Lines to Front Lines: Revitalizing the U.S. Defense Industrial Base for Future Great Power Conflict (Washington, DC: Center for a New American Security, 2025), https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/from-production-lines-to-front-lines; and Robert Greenway et al., “A Strategy to Revitalize the Defense Industrial Base for the 21st Century,” Heritage Foundation, 2025, https://www.heritage.org/defense/report/strategy-revitalize-the-defense-industrial-base-the-21st-century.

2 Jane Harman et al., Commission on the National Defense Strategy (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2024), https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/nds_commission_ final_report.pdf; Mark F. Cancian et al., The First Battle of the Next War: Wargaming a Chinese Invasion of Taiwan (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2023), https://www.csis.org/analysis/first-battle-next-war-wargaming-chinese-invasion-taiwan; and Stacie Pettyjohn et al., Dangerous Straits: Wargaming a Future Conflict Over Taiwan (Washington, DC: Center for a New American Security, 2022), https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/dangerous-straits-wargaming-a-future-conflict-over-taiwans.

3 For pre-2022 assessments, see Jacques S. Gansler, “Can the Defense Industry Respond to the Reagan Initiatives?” International Security 6, no. 4 (1982), 101–21, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2538680; Jacques S. Gansler, Democracy’s Arsenal: Creating a Twenty-First Century Defense Industry (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011); Julie C. Kelly et al., “Strengthening Industrial Base Decision-Making for Precision-Guided Munitions,” War on the Rocks, August 11, 2020, https://warontherocks.com/2020/08/strengthening-industrial-base-decision-making-for-precision-guided-munitions/; and Vital Signs 2021: The Health and Readiness of the Defense Industrial Base (Washington, DC: National Defense Industrial Association, 2021), https://www.ndia.org/-/media/sites/ndia/policy/vital-signs/2021/vital-signs_2021_digital.pdf.

4 Jim Fein, “How to Rebuild the Defense Industrial Base,” Heritage Foundation, May 2, 2025, https://www.heritage.org/defense/commentary/how-rebuild-the-defense-industrial-base.

5 For an exception to this argument, see Jennifer Kavanagh, “Why the United States Doesn’t Need an ‘Arsenal for Democracy’— And What To Do Instead,” Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, May 22, 2023, https://gjia.georgetown.edu/2023/05/22/why-the-united-states-doesnt-need-an-arsenal-for-democracy-and-what-to-do-instead/.

6 Wasser and Sheers, From Production Lines to Front Lines; Michael E. O’Hanlon and Alejandra Rocha, “Strengthening America’s Defense Industrial Base,” Brookings, June 20, 2024, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/strengthening-americas-defense-industrial-base/; Greenway et al., A Strategy to Revitalize the Defense Industrial Base for the 21st Century; Arthur Herman, Freedom’s Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II (New York: Random House, 2012); Tyler Hacker, Arsenal of Democracy: Myth or Model? Lessons for 21st-Century Industrial Mobilization Planning (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 2025), https://csbaonline.org/research/publications/arsenal-of-democracy-myth-or-model-lessons-for-21st-century-industrial-mobilization-planning; Roderick L. Vawter, Industrial Mobilization: The Relevant History (Washington, DC: National Defense University, 1983), https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA135528; Mark Harrison, “The Economics of World War II: An Overview,” in The Economics of World War II: Six Great Powers in International Comparison, ed. Mark Harrison (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1998); Stephen Broadberry and Mark Harrison, eds., The Economics of World War I (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

7 For important exceptions, see Mark F. Cancian, Industrial Mobilization: Assessing Surge Capabilities, Wartime Risk, and System Brittleness (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies 2021), https://www.csis.org/analysis/industrial-mobilization-assessing-surge-capabilities-wartime-risk-and-system-brittleness; Martin C. Libicki, Industrial Strength Defense: A Disquisition on Manufacturing, Surge, and War (Washington, DC: National Defense University, 1990), https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/html/tr/ADA228966/; Cynthia R. Cook, Reviving the Arsenal of Democracy: Steps for Surging Defense Industrial Capacity (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, March 14, 2023), https://www.csis.org/analysis/reviving-arsenal-democracy-steps-surging-defense-industrial-capacity; Mike Gallagher, “Hedging Our Bets: Reviving Defense Industrial Surge Capacity,” War on the Rocks, December 1, 2017, https://warontherocks.com/2017/12/hedging-bets-reviving-defense-industrial-surge-capacity/; Army Science Board, Surge Capacity in the Defense Munitions Industrial Base (Washington, DC: Headquarters Department of the Army, 2023), https://asb.army.mil/portals/105/reports/2020s/asb%20fy%2023%20dmib%20report%20(e).pdf.

8 Critically, producing and delivering a munition are distinct activities. This article focuses on the former while acknowledging that the latter can serve as a bottleneck as well.

9 U.S. Senate Preparedness Subcommittee, Investigation of the Ammunition Shortages in the Armed Services, U.S. Senate Committee on Armed Services, August 12, 1954, https://library.cqpress.com/cqalmanac/document.php?id=cqal53-1364082.

10 Ronald O’Rourke, Cruise Missile Inventories and NATO Attacks on Yugoslavia: Background Information, RS30162 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, April 20, 1999), https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA478026.

11 Frank Wolfe, “DOD Proposes Tripling JDAM Production to Replenish Stocks,” Defense Daily International, January 11, 2002; Benjamin S. Lambeth, NATO’s Air War for Kosovo: A Strategic and Operational Assessment (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2001), https://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1365.html.

12 Chris Krisinger, “Operation Nickel Grass: Airlift in Support of National Policy,” Airpower Journal 3, no. 1 (1989), 16–28, https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/ASPJ/journals/Volume-03_Issue-1-4/1989_Vol3_No1.pdf.

13 Walter J. Boyne, The Two O’Clock War: The 1973 Yom Kippur Conflict and the Airlift That Saved Israel (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2002), 163.

14 Joseph S. Doyle, “The Yom Kippur War and the Shaping of the United States Air Force” (MA thesis, Air University, June 2016),

https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/AD1030385; Vasabjit Banerjee and Benjamin Tkach, “Munitions Return to a Place of Prominence in National Security,” War on the Rocks, March 16, 2023, https://warontherocks.com/2023/03/munitions-return-to-a-place-of-prominence-in-national-security/.

15 Walter G. Hermes, Truce Tent and Fighting Front (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1992), 224–30, 230, https://history.army.mil/Publications/Publications-Catalog/Truce-Tent-and-Fighting-Front/.

16 Joslyn Fleming et al., Naval Logistics in Contested Environments (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2024), https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1921-1.html.

17 Paul D. Shinkman, “ISIS War Drains U.S. Bomb Supply,” U.S. News and World Report, February 17, 2017, https://www.usnews.com/news/world/articles/2017-02-17/us-raiding-foreign-weapons-stockpiles-to-support-war-against-the-islamic-state-group.

18 Wolfe, “DOD Proposes Tripling JDAM Production to Replenish Stocks.”

19 John A. Tirpak, “USAF Rebuilds Precision Munition Stockpiles,” Air and Space Forces Magazine, April 1, 2020, https://www.airandspaceforces.com/article/usaf-rebuilds-precision-munition-stockpiles/; and Shinkman, “ISIS War Drains U.S. Bomb Supply.”

20 Joint Chiefs of Staff, “Exercise Proud Saber 83 Detailed Analysis Report,” April 28, 1983, declassified July 31, 2014, https://www.esd.whs.mil/portals/54/documents/foid/reading%20room/mdr_releases/fy12/12-m-14890001.pdf.

21 Sandra R. Thomas, “Defense Industrial Base Sector Won’t Surge Without Policy Changes,” National Defense Magazine, April 2025, https://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/articles/2025/4/7/defense-industrial-base-sector-wont-surge-without-policy-changes.

22 For a discussion, see Mohamed Mellal, “Obsolescence—A Review of the Literature,” Technology in Society 63 (November 2020), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101347.

23 Fiscal Year 2021 Industrial Capability Report to Congress (Washington, DC: Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Industrial Base Policy, March 2023), 37–42, https://www.businessdefense.gov/docs/resources/FY2021-Industrial-Capabilities-Report-to-Congress.pdf.

24 Fiscal Year 2016 Annual Industrial Capabilities: Report to Congress (Washington, DC: Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics, March 2017), 87, https://www.businessdefense.gov/docs/resources/2016_AIC_RTC_06-27-17-Public_Release.pdf.

25 Government Accountability Office (GAO), Solid Rocket Motors: DOD and Industry Are Addressing Challenges to Minimize Supply Concerns, GAO-18-45 (Washington, DC: GAO, October 26, 2017), https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-18-45.

26 Supply Chain Illumination in the Department of Defense: Leveraging Private-Sector Best Practices to Enhance DOD Supply Chain Visibility and Decision Making (Washington, DC: Defense Business Board, 2025), https://dbb.defense.gov/portals/35/documents/reports/2025/final%20stamped%20-%20dbb%20supply%20chain%20illumination%20-%201-15-25%20-%20report.pdf.

27 See Sally Sleeper et al., “Identifying and Mitigating Industrial Base Risks for the DOD: Results of a Pilot Study,” Proceedings of the 11th Annual Acquisition Research Symposium, vol. 2, Thursday Sessions, April 30, 2014, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA624555; Christine Michienzi, “Finding Adversaries Hiding in the Defense Department’s Supply Chains,” War on the Rocks, March 12, 2025, https://warontherocks.com/2025/03/finding-adversaries-hiding-in-the-defense-departments-supply-chains/; Deborah G. Rosenblum, “Progress Report: Securing Defense-Critical Supply Chains,” Defense Acquisition Magazine, January–February 2023, https://www.dau.edu/library/damag/january-february2023/securingdefensecriticalsupplychains.

28 Cook, Reviving the Arsenal of Democracy.

29 Cynthia Cook, “Pressing Challenges to U.S. Army Acquisition: A Conversation With Hon. Douglas R. Bush,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, March 3, 2023, https://www.csis.org/analysis/pressing-challenges-us-army-acquisition-conversation-hon-douglas-r-bush.

30 “Resilient Defense Industrial Base Critical for Deterring Conflict,” Department of Defense (DOD), October 25, 2023, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3569067/resilient-defense-industrial-base-critical-for-deterring-conflict/.

31 “Ukraine Contracting Actions,” DOD, January 13, 2023, https://media.defense.gov/2023/jan/13/2003144570/-1/-1/0/contracting-fact-sheet-13jan.pdf.

32 GAO, Ukraine: Status and Use of Supplemental U.S. Funding, as of First Quarter, Fiscal Year 2024, GAO-24-107232 (Washington, DC: GAO, May 30, 2024), https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-24-107232.

33 James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023, Pub. L. No. 117–263 (2022); Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment, “Class Deviation—Temporary Authorizations for Covered Contracts Related to Ukraine,” DARS Tracking Number 2023-O0003, December 23, 2022, https://www.acq.osd.mil/dpap/policy/policyvault/USA002482-22-DPC.pdf; and “Ukraine Contracting Actions.”

34 “Memorandum on the Presidential Waiver of Statutory Requirements Pursuant to Section 303 of the Defense Production Act of 1950, as Amended,” The White House, October 3, 2022, https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2022/10/03/memorandum-on-the-presidential-waiver-of-statutory-requirements-pursuant-to-section-303-of-the-defense-production-act-of-1950-as-amended/.

35 State of American Cybersecurity: Hearing Before the House Armed Services Comm. Subcomm. on Cyber, Information Technologies, and Innovation, 118th Cong., 1st sess. (March 23, 2023) (statement of William A. LaPlante, Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment), https://armedservices.house.gov/sites/evo-subsites/republicans-armedservices.house.gov/files/laplante%20testimony.pdf and https://armedservices.house.gov/calendar/eventsingle.aspx?EventID=3612.

36 Matthew Sablan and Matthew Howard, “DOD Renews PEO Summit to Improve Acquisition Collaboration,” DOD, July 18, 2023, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3462460/dod-renews-peo-summit-to-improve-acquisition-collaboration/.

37 “Fact Sheet on Efforts of Ukraine Defense Contact Group—National Armaments Directors,” DOD, September 6, 2024, https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3897721/fact-sheet-on-efforts-of-ukraine-defense-contact-group-national-armaments-direc/.

38 The maximum rate can be achieved through additional shifts. See DOD 7000.14-R, Department of Defense Financial Management Regulation (Washington, DC: DOD, February 2025), https://comptroller.defense.gov/fmr/fmrAlert.aspx.

39 “Ukraine Contracting Actions.”

40 Darrell Ames, “Army Awards Contracts to Accelerate Javelin and Stinger Production,” DOD, May 31, 2022, https://www.dvidshub.net/news/421879/army-awards-contracts-accelerate-javelin-and-stinger-production.

41 Hearing on the Fiscal Year 2023 Army Modernization Programs Budget Request: Hearing Before the House Armed Services Subcomm. on Tactical Air and Land Forces, 117th Cong., 2nd sess. (May 17, 2022) (verbal testimony of Douglas R. Bush, Assistant Secretary of the Army for Acquisitions, Logistics, and Technology), https://democrats-armedservices.house.gov/2022/5/subcommittee-on-tactical-air-and-land-forces-hearing-fiscal-year-2023-army-modernization-programs; and Ames, “Army Awards Contracts to Accelerate Javelin and Stinger Production.”

42 “Contracts for May 27, 2022,” DOD, https://www.defense.gov/News/Contracts/Contract/Article/3046664/.

43 Valerie Insinna, “Facing Obsolete Parts, Raytheon Struggling to Replace Stingers Sent to Ukraine,” Breaking Defense, April 26, 2022, https://breakingdefense.com/2022/04/facing-obsolete-parts-raytheon-struggling-to-replace-stingers-sent-to-ukraine.

44 Kevin Jackson, “Stinger Maintenance Work to Increase Service Life, Reliability,” U.S. Army, May 25, 2017, https://www.army.mil/article/188420/stinger_maintenance_work_ to_increase_service_life_reliability.

45 Hearing to Receive Testimony on the Health of the Defense Industrial Base: Hearing Before the U.S. Senate Comm. on Armed Services, 117th Cong., 2nd sess. (April 26, 2022), https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/hearings/to-receive-testimony-on-the-health-of-the-defense-industrial-base.

46 Insinna, “Facing Obsolete Parts, Raytheon Struggling to Replace Stingers Sent to Ukraine.”

47 Marcus Weisgerber, “Raytheon Calls in Retirees to Help Restart Stinger Missile Production,” Defense One, June 28, 2023, https://www.defenseone.com/business/2023/06/raytheon-calls-retirees-help-restart-stinger-missile-production/388067/; Hearing to Receive Testimony on the Health of the Defense Industrial Base.

48 Marcus Weisgerber, “Aerojet Rocketdyne Struggling to Deliver Rocket Motors, Raytheon CEO Says,” Defense One, December 7, 2022, https://www.defenseone.com/business/2022/12/aerojet-rocketdyne-struggling-deliver-rocket-motors-raytheon-ceo-says/380562/.

49 Chris Laudati, “The Precarious State of U.S. Defense Stockpiles,” National Defense Magazine, November 18, 2022, https://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/articles/2022/11/18/the-precarious-state-of-us-defense-stockpiles.

50 David Hambling, “Reassessing ‘Saint Javelin’: Crunching Anti-Tank Missile Numbers,” Forbes, November 8, 2024, https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidhambling/2024/11/08/re-assessing-saint-javelin-crunching-anti-tank-missile-numbers/; and Maya Carlin, “How the Javelin Missile Became Russia’s Worst Nightmare,” National Interest, February 21, 2025, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/how-the-javelin-missile-became-russias-worst-nightmare.

51 “Fact Sheet on U.S. Security Assistance to Ukraine,” DOD, January 8, 2025, https://media.defense.gov/2025/jan/09/2003626080/-1/-1/1/ukraine-fact-sheet-jan-9-2025.pdf.

52 Mark F. Cancian, “Is the United States Running Out of Weapons to Send to Ukraine?” Center for Strategic and International Studies, September 16, 2022, https://www.csis.org/analysis/united-states-running-out-weapons-send-ukraine; Hearing to Receive Testimony on the Health of the Defense Industrial Base.

53 Joe Gould, “Lockheed, Aiming to Double Javelin Production, Seeks Supply Chain ‘Crank Up,’” Defense News, May 9, 2022, https://www.defensenews.com/industry/2022/05/09/lockheed-aiming-to-double-javelin-production-seeks-supply-chain-crank-up/.

54 Ames, “Army Awards Contracts to Accelerate Javelin and Stinger Production.”

55 “Javelin Replacement Contract Awarded,” DOD, September 15, 2022, https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3159196/javelin-replacement-contract-awarded/; “Army Announces Contract Award for Javelin Missile System,” U.S. Army, April 21, 2023, https://www.army.mil/article/266368/army_announces_contract_award_for_javelin_missile_system.

56 GAO, Ukraine: Status and Challenges of DOD Weapon Replacement Efforts, GAO-24-106649 (Washington, DC: GAO, April 30, 2024), https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-24-106649.

57 Justification Book of Missile Procurement, Army: DOD Fiscal Year 2023 Budget Estimates (Washington, DC: Headquarters Department of the Army, April 2022), https://www.asafm.army.mil/Portals/72/Documents/BudgetMaterial/2023/Base%20Budget/Procurement/MSLS_ARMY.pdf.

58 GAO, Solid Rocket Motors.

59 Audrey Decker, “L3Harris Points to Suppliers for Slowdown in Rocket-Motor Production,” Defense One, October 27, 2023, https://www.defenseone.com/business/2023/10/l3harris-points-suppliers-slowdown-rocket-motor-production/391587/; and Weisgerber, “Aerojet Rocketdyne Struggling to Deliver Rocket Motors, Raytheon CEO Says.”

60 Doug Cameron, “Biden Visits Lockheed Plant as U.S. Boosts Javelin Production for Ukraine,” Wall Street Journal, May 3, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/politics/national-security/lockheed-hunts-for-workers-as-u-s-ramps-up-javelin-production-for-ukraine-11651587400; “U.S. Army Awards Javelin Production Contract,” Lockheed Martin, May 4, 2023, https://news.lockheedmartin.com/2023-05-04-us-army-awards-javelin-production-contract; “Orange County Expansion Helps Aerojet Rocketdyne Boost Solid Rocket Motor Production,” L3Harris, May 30, 2024,

https://www.l3harris.com/newsroom/editorial/2024/05/orange-county-expansion-helps-aerojet-rocketdyne-boost-solid-rocket; Audrey Decker, “Aerojet Digging ‘Out of this Hole’ As It Clears Rocket Backlog, President Says,” Defense One, September 27, 2024, https://www.defenseone.com/business/2024/09/aerojet-digging-out-hole-it-clears-rocket-backlog-president-says/399905/; and Cameron, “Biden Visits Lockheed Plant.”

61 “USD (Policy) Dr. [Colin] Kahl Press Conference,” DOD, August 8, 2022, https://www.defense.gov/News/Transcripts/Transcript/Article/3120707/usd-policy-dr-kahl-press-conference/; C. Todd Lopez, “Advanced Rocket Launcher System Heads to Ukraine,” DOD, June 1, 2022,

https://www.war.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3050010/advanced-rocket-launcher-system-heads-to-ukraine/; Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System/Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System Alternative Warhead: Modernized Selected Acquisition Report (Washington, DC: DOD, December 31, 2023), https://www.esd.whs.mil/portals/54/documents/foid/reading%20room/selected_acquisition_reports/fy_2023_sars/gmlrs_gmlrs_aw_msar_dec_2023.pdf.

62 Morgan Douro, “MLRS and the Totality of the Battlefield,” Royal United Services Institute, February 21, 2023, https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/mlrs-and-totality-battlefield; Kris Osborn, “Who Needs Air Superiority? U.S. GMLRS Are Pounding Russia in Ukraine,” National Interest, August 11, 2023, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/who-needs-air-superiority-us-gmlrs-are-pounding-russia-ukraine-204141; and C. Todd Lopez, “$1 Billion Support Package for Ukraine, Largest Yet,” DOD, August 8, 2022, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3120645/1-billion-support-package-for-ukraine-largest-yet/.

63 “Reprogramming Action—Internal Reprogramming: Ukraine Replacement Transfer Fund Tranche #6,” DOD Comptroller, August 2, 2022,

https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/execution/reprogramming/fy2022/ir1415s/FY22-38_IR_Ukraine_Replacement_6_signed_20220802.pdf.

64 “Army Awards Contracts for Guided Multiple Launch Rocket Systems,” U.S. Army, November 14, 2022, https://www.army.mil/article/261980/army_awards_contracts_for_guided_multiple_launch_rocket_systems.

65 Justification Book of Missile Procurement, Army: DOD Fiscal Year (FY) 2022 Budget Estimates (Washington, DC: Headquarters Department of the Army, May 2021), https://www.asafm.army.mil/Portals/72/Documents/BudgetMaterial/2022/Base%20Budget/Procurement/MSLS_FY_2022_PB_ Missile_Procurement_Army.pdf.

66 “Lockheed Martin to Develop Modular Pods for Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System,” Lockheed Martin, May 15, 2019, https://news.lockheedmartin.com/2019-05-15-Lockheed-Martin-to-Develop-Modular-Pods-for-Guided-Multiple-Launch-Rocket-System; and Justification Book of Missile Procurement, Army, 2022.

67 Justification Book of Missile Procurement, Army: DOD Fiscal Year (FY) 2021 Budget Estimates (Washington, DC: Headquarters Department of the Army, February 2020), https://www.asafm.army.mil/Portals/72/Documents/BudgetMaterial/2021/Base%20Budget/Procurement/MSLS_FY_2021_PB_ Missile_Procurement_Army.pdf.

68 Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System/ Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System Alternative Warhead; and Michael Marrow, “Lockheed on ‘Campaign-Like’ Hunt for New Solid Rocket Motor Supplier—or Suppliers,” Breaking Defense, October 17, 2023, https://breakingdefense.com/2023/10/lockheed-on-campaign-like-hunt-for-new-solid-rocket-motor-supplier-or-suppliers/.

69 Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System/Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System Alternative Warhead.

70 Sam Skove, “Why It’s Hard to Double GMLRS Production,” Defense One, March 30, 2023, https://www.defenseone.com/business/2023/03/why-its-hard-double-gmlrs-production/384646/.

71 Ryan Brobst et al., “Can the U.S. Arm Itself and Ukraine?” Foundation for Defense of Democracies, July 15, 2025, https://www.fdd.org/analysis/2025/07/15/can-the-u-s-arm-itself-and-ukraine/; and “Signed, Sealed, Delivered: Lockheed Martin Delivers First Upgraded PAC-3 Missile Interceptors,” Lockheed Martin, October 6, 2015, https://news.lockheedmartin.com/2015-10-06-Signed-Sealed-Delivered-Lockheed-Martin-Delivers-First-Upgraded-PAC-3-Missile-Interceptors.

72 “Senior Defense Official and Senior Military Official Hold a Background Briefing,” DOD, December 21, 2022, https://www.defense.gov/News/Transcripts/Transcript/Article/3253239/senior-defense-official-and-senior-military-official-hold-a-background- briefing/; “Senior Defense and Senior Military Official Hold a DOD Background Briefing on Ukraine,” DOD, December 17, 2024, https://www.defense.gov/News/Transcripts/Transcript/Article/4009301/senior-defense-and-senior-military-official-hold-a-dod-background-briefing-on-u/; and “Reprogramming Action—Internal Reprogramming: June Ukraine Tranche Return,” DOD Comptroller, July 27, 2023, https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/execution/reprogramming/ fy2023/ir1415s/23-55_IR_Ukraine_Replacement_Transfer_Fund_Return.pdf.

73 DOD, “Ukraine Security Assistance,” January 8, 2025, https://media.defense.gov/2025/jan/08/2003626039/-1/-1/0/ukraine-infographic-19dec2024.pdf; DOD, “Fact Sheet on Efforts of Ukraine Defense Contact Group—National Armaments Directors”; and Brobst et al., “Can the U.S. Arm Itself and Ukraine?”

74 Patriot Advanced Capability-3 Missile Segment Enhancement: Modernized Selected Acquisition Report (Washington, DC: DOD, December 31 2023), https://www.esd.whs.mil/portals/54/documents/foid/reading%20room/selected_acquisition_reports/fy_2023_sars/pac-3_mse_msar_dec_2023.pdf. See also “Reprogramming Action—Internal Reprogramming: Critical Munitions Defense Funding,” DOD Comptroller, June 9, 2022, https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/execution/reprogramming/fy2022/ir1415s/22-26_IR_Critical_Munitions_Defense_Funding_Request.pdf.

75 DOD, “Ukraine Security Assistance”; and Brobst et al., “Can the U.S. Arm Itself and Ukraine?”

76 Justification Book of Missile Procurement, Army, 2022.

77 Megan M. Evans, “Why Does This Have to be So Complicated?” United States Army Acquisition Support Center, September 9, 2021, https://asc.army.mil/web/news-why-does-this-have-to-be-so-complicated/.

78 “Lockheed Martin Opens Facility to Increase PAC-3 Production,” Lockheed Martin, October 4, 2022, https://news.lockheedmartin.com/2022-10-04-new-lockheed-martin-facility-to-support-increased-pac-3-production.

79 Jason Sherman, “Lockheed Martin Doubling PAC-3 MSE Production Capacity in 2022 to Meet Demand,” Inside Defense, November 11, 2021, https://insidedefense.com/share/213222?0; and Jen Judson, “How Companies Plan to Ramp Up Production of Patriot Missiles,” Defense News, April 9, 2024, https://www.defensenews.com/land/2024/04/09/how-companies-plan-to-ramp-up-production-of-patriot-missiles/.

80 “Production Plan on Patriot Missiles for 2025 Announced, It Will Need Every Contractor to Quicken Up,” Defense Express, March 27, 2025, https://en.defence-ua.com/industries/production_plan_on_patriot_missiles_for_2025_announced_it_will_need_every_contractor_to_quicken_up-13981.html.

81 “Boeing Says It’s Ramping Up Seeker Production as Patriot Demand Surges,” Reuters, August 7, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/boeing-says-its-ramping-up-seeker-production-patriot-demand-surges-2024-08-07/; and “Production Plan on Patriot Missiles for 2025 Announced.”

82 Cook, Reviving the Arsenal of Democracy.

83 “Remarks by Secretary Pete Hegseth at the Army War College (As Delivered),” DOD, April 23, 2025, https://www.defense.gov/News/Speeches/Speech/Article/4164715/remarks-by-secretary-of-defense-pete-hegseth-at-the-army-war-college-as-deliver/; “Remarks by Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth at the 2025 Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore (As Delivered),” DOD, May 31, 2025, https://www.defense.gov/News/Speeches/Speech/article/4202494/remarks-by-secretary-of-defense-pete-hegseth-at-the-2025-shangri-la-dialogue-in/; and DOD Instruction 4245.16, Joint Production Accelerator Cell (Washington, DC: DOD, January 17, 2025), https://www.esd.whs.mil/portals/54/documents/dd/issuances/dodi/424516p.pdf.

84 See Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement, “252.217-7001, Surge Option,” DOD, January 17, 2025, https://www.acquisition.gov/dfars/252.217-7001-surge-option.

85 Sandra R. Thomas, “Putting the Defense Industry Through Wargames,” War on the Rocks, June 23, 2025, https://warontherocks.com/2025/06/putting-the-defense-industry-through-wargames/.

86 Michael Horowitz and Joshua Schwartz, “Stealth and Scale: Quality, Quantity, and Modern Military Power,” War on the Rocks, December 18, 2024, https://warontherocks.com/2024/12/stealth-and-scale-quality-quantity-and-modern-military-power/.