Download PDF

Michael F. Harsch is an Associate Professor of National Security in the Dwight D. Eisenhower School for National Security and Resource Strategy at the National Defense University. Lieutenant Colonel Shaun Lee, USAF, is Air Force Element Commander in the Joint Intelligence Operations Center at U.S. Indo-Pacific Command.

The end of the Cold War ushered in three decades of rapid globalization and economic growth, with the number of people living in extreme poverty dropping by more than 1 billion globally.1 Supply chains grew increasingly complex, and companies profited from prioritizing efficiency over resilience and security. Yet a series of international crises has forced a global reckoning of the risks of economic entanglement: heightened trade competition between the United States and China, the global COVID-19 pandemic, and the war in Ukraine all exposed critical vulnerabilities in global supply chains.

In response, scholars have proposed the concept of weaponized interdependence to analyze how states exploit growing global interconnectedness to their advantage,2 and the Group of Seven (G-7) countries have agreed on “de-risking” their economic relations with China.3 One of the most publicized policy changes in recent years has been shifting critical supply chains toward like-minded nations, an effort known as friend-shoring.4 From a U.S. perspective, the goal is to increase supply chain security by rerouting the flow of goods and services from geostrategic competitors to friendly countries, which are less likely to engage in economic coercion. Senior members of the second Trump administration have reaffirmed the importance of securing supply chains,5 with Secretary of State Marco Rubio declaring that “relocating our critical supply chains to the Western Hemisphere would . . . safeguard Americans’ own economic security.”6 Skeptics caution that friend-shoring carries its own risks, such as dividing the world into economic blocs and raising production and consumer prices.7 Proponents counter that the approach is needed only to protect a few critical sectors and that the term friend is not limited to liberal democracies but offers the United States the opportunity to include a wider range of countries with shared security and economic interests.8 As former Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen put it, friend-shoring could thereby lead to “free but secure trade . . . with the countries we know we can count on.”9

This raises an important question: Which are the countries that the United States can count on,” and how can it know? Current friend-shoring initiatives typically use an ad hoc, case- by-case approach—rather than a simple, transparent, and universally applicable measure—to gauge the reliability of potential partners. This article introduces a new approach to measuring a country’s or coalition’s reliability, that is, its likelihood of honoring a commitment.

We estimate a state’s reliability based on past and likely future behavior. First, we leverage states’ voting behavior in the United Nations (UN) General Assembly, which reveals countries’ alignment with U.S. positions in the recent past (so- called ideal points).10 This component of our measure accounts for the observed behavior of potential partners.11 Second, as past behavior is not a perfect predictor of future behavior, we combine UN voting data with a widely used indicator of countries’ levels of democracy— Freedom House’s Global Freedom Scores. As states with strong democratic institutions have a better track record of upholding their international commitments,12 this pattern plausibly extends to friend-shoring initiatives. Taken together, past and likely future behavior help us to quantify a state’s reliability with a simple score.

We proceed as follows. The next section outlines the concept of friend- shoring and explains our new measure of reliability. We then illustrate the usefulness of our measure with a historical case study on U.S. vulnerability to oil supply shocks, as exposed by the 1973 embargo by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and the resulting U.S. efforts to import oil from more closely aligned nations. Finally, we use the measure to assess current U.S. friend-shoring initiatives on securing access to critical minerals and microchips. We conclude that by effectively balancing cost and risk, this approach could expand the capacity and capability of the U.S. defense industrial base.

Friend-Shoring: Concept and Measurement

Concept. There is a long history of governments trying to direct trade flows. A historic example is the Hanseatic League, a trade bloc of cities in northern Europe that lasted from the 13th to the 17th century. Today, a dense net of trade agreements exists around the world, such as the United States– Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA). These arrangements typically include a large set of trade rules and limitations, spanning multiple industries.

Yet the concept of friend-shoring is relatively new. Concerns about global supply chain disruptions grew as U.S.- China trade competition escalated in 2018 and 2019.13 But in U.S. public discourse, the idea of redirecting trade to friendly nations emerged only in 2021 and 2022 amid the severe supply chain disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. The idea was popularized in a June 2021 article by the economists Elaine Dezenski and John Austin. They argued that relocating production to other countries purely based on their comparative advantage had become too risky, but returning all production to the United States was too costly. Hence, they proposed expanding trade and coproduction relationships with allied nations, which they called ally-shoring.14

As the idea took off, policymakers broadened the term to friend-shoring,15 and by the end of 2022, Foreign Policy featured the term on a short list of “new geopolitical vocabulary.”16 Friend-shoring refers to the relocation of manufacturing and sourcing to geopolitically aligned countries, with the goal of reducing risks from weaponized economic interdependence. Relying on a wide set of like-minded countries, rather than only treaty allies, has both political and economic advantages: it provides policymakers with greater flexibility when selecting partners and allows for stronger diversification and gains from comparative advantage. While ally-shoring plays it safe, friend-shoring aspires to play it smart.

However, friend-shoring involves difficult trade-offs.17 Picking friends violates the economic bedrock principle of comparative advantage: the selection of production sites and sources based on cost considerations alone. Friend-shoring is thus less efficient than unconstrained offshoring. High estimates indicate economies could suffer output losses of up to 4.7 percent of gross domestic product, depending on how widely friend-shoring is being used.18 In reality, costs would likely be far lower because the United States and other states seek to limit friend-shoring to a small number of critical sectors, such as critical minerals and microchips. Crucially, higher production costs due to friend-shoring are justifiable if they increase supply chain security and mitigate supply shocks.19

The success of friend-shoring ultimately hinges on getting the selection of partner nations right. In contrast to the term ally, friend is not a well-established concept in international relations.20 There is little agreement on how to gauge the risks involved in friend-shoring initiatives, and existing measures, such as the World Bank’s “Ease of Doing Business” ranking, typically rely on information provided by the country in question. As a result, these metrics are vulnerable to political pressure: in 2021, the World Bank decided to discontinue the influential Doing Business ranking after some of its senior officials were accused of manipulating data to boost China’s score.21 To determine the reliability of potential partners, we pro- pose a transparent measure that focuses on political risks and does not rely on data from the affected countries.

Measure. Our proposed Measure of Country Reliability (MCR) aims to estimate the reliability of potential partner nations from a U.S. perspective. The MCR combines two indicators that capture past and likely future behavior of potential partner nations. The table summarizes the measure.

To develop the MCR, we extend important work on alliances between states and among firms.22 Scholarship for both international relations and organizational science is salient for friend-shoring, as these initiatives involve both government and corporate actors and connect foreign policy with defense industrial strategy.23 A host of studies confirms an intuitive finding: as alliances tend to have high stakes and their failure could threaten the survival of a given state or firm, one of the most important criteria for selecting new partners is their reputation for being reliable.24

Most research on reliability in inter- national relations harnesses observable past behavior to estimate reliability. For example, studies use data on instances in which states reneged on their alliance commitments.25 When it comes to friend- shoring, however, there are few historical cases that states (and scholars) could use to gauge reliability.

A clear, easily observable alternative is states’ voting records in the UN General Assembly, in which states are forced to take sides and reveal their preferences. Researchers have long relied on UN vot- ing behavior to determine geopolitical alignment and, more recently, to analyze friend-shoring.26 For instance, one study uses UN voting data to divide the world into potential trade blocs and then conduct a series of simulations on the costs of friend-shoring.27 We therefore leverage UN voting behavior in our measure, too.

We use existing data on national “ideal points” for each UN member state that reveal the level of states’ support for the U.S.-led liberal, or rules-based, international order. Ideal points are a widely used statistical method to estimate the position of legislators on the left/right or other political dimensions by observing the votes they cast. In the case of the United Nations, the legislature is the UN General Assembly, where all member states regularly vote on resolutions.

According to an influential study, the most relevant dimension, or dividing line, in the UN General Assembly is “the position of states vis-à-vis a U.S.-led liberal order.” As the authors explain, “During the Cold War, this was the East-West conflict between communist and capitalist states. Since the end of the Cold War, the non-Western pole has been occupied by a motley crew of states that have little ideological cohesion other than their op- position to the Western liberal order.”28

As UN voting behavior reveals support for a U.S.-led rules-based order, we assume that it is a good indicator of geo- political and economic reliability from a U.S. perspective. A dataset maintained by the political scientist Erik Voeten provides ideal points for all UN member states: the higher the ideal point value, the more supportive a country is of the U.S.-led liberal order. The United States has the highest ideal point of all country-years from 1946 to 2023—as one would expect given its inherent interest in promoting a U.S.-led world order—and the Soviet Union the lowest.29 Values range from -2.986 to 3.188 over time, but these numbers are hard to interpret. We therefore normalize these ideal points to a 0-to-100 scale for each year. A value of 100 means that among all UN member states, this state’s votes were most aligned with the U.S.-led order; by contrast, 0 signifies the least alignment of all states. We use the average of the past 3 years.30

However, as the voting data captures past behavior, it is not necessarily predictive of future behavior, which should be given equal consideration. Partnerships need not only to be secure but also to endure. For instance, research shows that, especially, leadership changes in nondemocratic countries tend to affect UN General Assembly voting.31 Thus, we should consider not only countries’ voting behavior but also their political systems.

To predict future behavior, we focus on regime type, specifically on a given state’s level of democracy. It may seem intuitive that democracies are inherently better candidates for supply chain security, as they are more likely to share fundamental views on governance, market economics, and human rights.32 Perhaps surprisingly, democracies have also proved more consistent in foreign policy than their autocratic counterparts. In his influential book Reliable Partners, Charles Lipson argues that democracies are more reliable allies because their transparent political systems make bluffing and deception difficult. As a result, making deals with democracies is generally less risky than making deals with autocracies.33 This argument is supported by mounting empirical evidence.34 One influential study found that autocracies are three times more likely to reverse course on international agreements than democracies; furthermore, democratic transfers of power are eight times less likely to result in the abrogation of foreign policy agreements than if an autocratic ruler is deposed.35

To determine countries’ level of democracy, we use the Global Freedom Scores provided by Freedom House, a U.S.-based nonprofit organization founded in 1941. The annual scores combine ratings on civil liberties (0 to 60 points) and political rights (0 to 40 points) to assess a nation’s overall freedom level. The maximum score is thus 100.36 In 2023, the spectrum ranged from Finland, Norway, and Sweden, which received perfect scores of 100, to South Sudan and Syria, whose rating was just 1.37

Figure 1 shows the MCR scores for the G-20 economies in 2023. The figure further depicts both components of the MCR, illustrating that each is important. For example, Russia votes slightly more reliably with the United States than India does; however, the two countries differ significantly in their Freedom House scores. Conversely, Mexico and Indonesia have similar Freedom House scores but differ significantly in their UN voting behavior, with Mexico being more aligned with the United States. Figure 2 shows a map of MCR scores across the globe. In both figures, we omit the U.S. score because the MCR is designed to estimate reliability from a U.S. perspective.

One important limitation of the measure is that voting data exists only for UN member states. Hence, there is no data on Taiwan, which dominates the global production of advanced microchips. Yet it is still possible to estimate a score for Taiwan. Freedom House rates the level of democracy in Taiwan (94 on a scale of 100 in 2023). We further assume that the lack of UN membership signals high risks associated with Taiwan’s contested status. This assessment is supported by the fact that the United States is investing billions in domestic microchip manufacturing to lessen its reliance on production in Taiwan.38 We therefore rate Taiwan 0 on this dimension, which suggests an MCR of 94 in 2023, or moderate risk.39

Applying the Measure to a Historical Case: The 1973 Oil Embargo

By the early 1970s, the United States imported nearly one-third of the oil it consumed, overwhelmingly from OPEC member states.40 Applying the MCR confirms the intuition that this dependence on OPEC posed significant risks for the U.S. economy. Based on UN voting behavior and Freedom House ratings prior to the crisis, OPEC’s 12 members—Algeria, Ecuador, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Nigeria, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Venezuela—had an average reliability score of just 67 out of 200 in 1973 (see figure 3).41

On October 6, 1973, during the Jewish holiday of Yom Kippur, Syria and Egypt launched a surprise attack against Israel. Although neither Syria nor Egypt was a member of OPEC, most members of the organization imposed a 5-month embargo on oil exports to the United States to discourage Washington from supporting Israel. The psychological impact of the embargo was profound and increased OPEC’s perceived influence over oil markets to an “almost mythical status.”42 By January 1974, the price of crude oil skyrocketed fourfold from $3.06 a barrel to $11.65 a barrel, sending the Figure 1 shows the MCR scores for the G-20 economies in 2023. The figure further depicts both components of the MCR, illustrating that each is important. For example, Russia votes slightly more reliably with the United States than India does; however, the two countries differ significantly in their Freedom House scores. Conversely, Mexico and Indonesia have similar Freedom House scores but differ significantly in their UN voting behavior, with Mexico being more aligned with the United States. Figure 2 shows a map of MCR scores across the globe. In both figures, we omit the U.S. score because the MCR is designed to estimate reliability from a U.S. perspective. One important limitation of the measure is that voting data exists only for UN member states. Hence, there is no data on Taiwan, which dominates the global production of advanced microchips. Yet it is still possible to estimate a score for Taiwan. Freedom House rates the level of democracy in Taiwan (94 on a scale of 100 in 2023). We further assume that the lack of UN membership signals high risks associated with Taiwan’s contested status. This assessment is supported by the fact that the United States is investing billions United States into an economic crisis.43

The events had a lasting impact on the American economy and energy policy. According to inflation-adjusted data provided by the Department of Energy, gas pump prices progressively declined from the mid-1950s until 1972 but jumped on average by 25 percent from 1973 to 1974. Iran’s 1979 revolution then sparked a second oil crisis within one decade, with U.S. gas prices in 1980 surging to a level more than 80 percent higher than those in 1973.44 Fiscal and monetary policies aimed at curbing inflation led to low economic growth in the United States during much of the 1970s and early 1980s. However, growing concerns about OPEC’s influence over global oil markets also drove the United States to diversify its energy portfolio.

The oil embargo illustrates the usefulness of our measure. An average score of 67 for OPEC members in 1973 indicates high risks for the U.S. oil supply at the time. In addition, it is striking that the two highest-ranked OPEC members that year—Venezuela (141) and Ecuador (86), as shown in figure 3—did not participate in the embargo.45 Thus, both turned out to be more reliable partners for the United States, as predicted by their higher MCR.

Five decades later, the shale revolution has dramatically increased domestic production of oil and natural gas in the United States, alongside a burgeoning renewable energy sector. In 2020, the United States became a net exporter of petroleum.46 While the United States still imports some oil, it originates from starkly different partners than in the 1970s. In November 2023, 63 percent of American oil imports came from Canada, followed by Mexico (10.5 percent) and Colombia (3.5 percent).47 Taken together, these three countries from the Americas provided more than three-quarters of U.S. oil imports. By contrast, OPEC, as an export bloc, accounted for a paltry 12 percent, down from 75 percent during the 1973 crisis. According to our measure, this shift has significantly reduced America’s exposure to risk. Canada, by far the largest foreign source of oil for the United States, has an MCR of 171, indicating a low level of risk. While Mexico (103) and Colombia (114) both fall into the moderate risk category, their reliability scores are significantly higher than OPEC’s 1973 average (67).

The combination of stronger domestic production and a shift to more reliable oil suppliers has paid off during two recent crises, presenting a stark contrast to the oil crises of the 1970s. First, in February 2022, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine disrupted global oil markets, and gas pump prices increased by 42 percent at their peak.48 However, unlike in the post-1973 period, the spike was short-lived, and there was no rationing. Prices returned to prewar levels after approximately 6 months (see figure 4). Then, on October 7, 2023, Hamas’s surprise attack on Israel—50 years after the Yom Kippur War—ignited regional turmoil. Remarkably, U.S. gas pump prices fell in the following months, and by February 2025, after one-and-a-half years of seismic shifts in the Middle East’s balance of power, prices remained below pre–October 7 levels. Although many factors influence global crude oil and gas pump prices, decades of friend-shoring have arguably contributed to a largely shock-proof U.S. oil supply.

Applying MCR to Current Friend-Shoring Initiatives

Current U.S. friend-shoring initiatives seek to build resilient supply chains in a small number of critical sectors. In 2021, the U.S. Government identified four key industrial products with significant supply chain vulnerabilities: critical minerals and materials, semiconductors, large-capacity batteries, and pharmaceuticals.49 To date, the United States has initiated notable friend-shoring programs in the first two of those four areas—the Minerals Security Partnership (MSP) for critical minerals, and the Chip 4 Alliance and other regional initiatives for semiconductors. These initiatives are still nascent, with the long-term goal of strengthening critical supply chains through deliberate partnerships with like-minded nations. Although it is too early to assess their effectiveness, our new measure can offer insights into how to evaluate supply chain risks inside and outside these partnerships.

Critical Minerals: The Minerals Security Partnership. The U.S. Government has defined any minerals and materials as critical if they “are needed to supply the military, industrial, and essential civilian needs of the United States during a national emergency, and not found or produced in the United image Figure 5. MCR for Minerals Security Partnership Members image States in sufficient quantities to meet such need.”50 More than 250 materials meet these criteria. For 46 of these materials, the United States imports more than half its consumption.51 China controls half of global mining capacity and 85 percent of refining capacity for strategic and critical materials.52 This has raised concerns across the political spectrum, with then Senator Rubio warning of China’s influence over “the price and volume of all critical mineral goods in the global market.”53

Applying the MCR highlights the supply chain risks for many critical min- erals. For example, vanadium is a rarely occurring mineral used for hardened steel alloys like those found in space vehicles, nuclear reactors, and ships.54 China and Russia (both high risk, with MCRs of 39 and 58) control over 80 percent of the world’s vanadium market share.55 In the case of gallium—a soft metal used in many semiconductors—China supplied a staggering 98 percent of global output in 2022.56 Finally, China supplies 84 percent of the world’s rare earths, a dominance that China has been willing to use for economic coercion.57 For example, in 2010, in response to a territorial dispute with Japan, China abruptly limited rare earth exports, causing global prices to spike 300 to 500 percent, underscoring the extreme vulnerability associated with China’s near monopoly.58

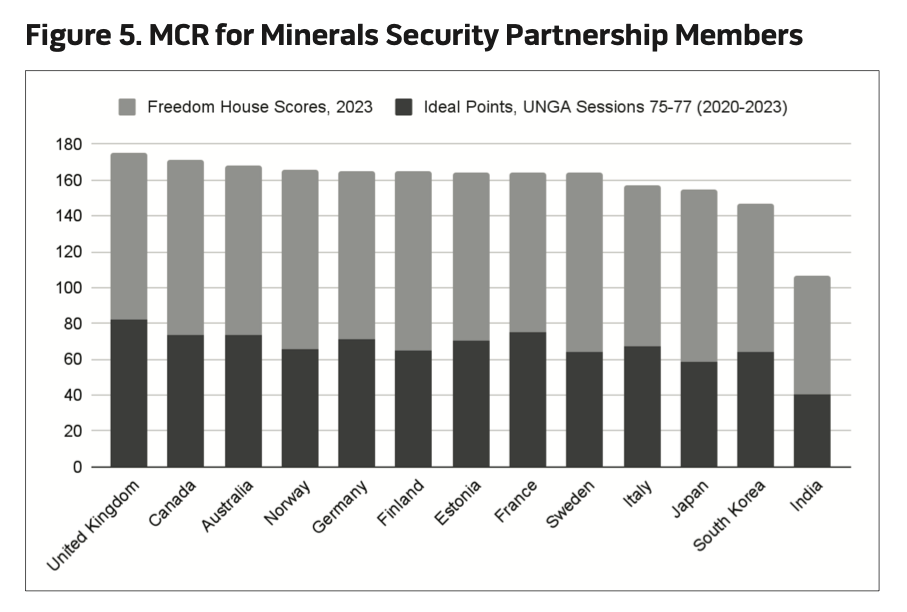

To mitigate the risks posed by China’s critical minerals monopoly, the United States in June 2022 launched the MSP, which has evolved into a pact with 13 other countries and the European Union (see figure 5 for MCR scores).59 According to the State Department, the partnership is a deliberate effort to work with partner nations to build diverse, sustainable supply chains for critical minerals.60 In practice, the initiative offers mineral-endowed nations an alternative to Chinese-dominated supply chains. Currently, the MSP sponsors 23 projects, the majority of which involve mining, mineral extraction, and mineral processing.61

Our measure suggests that the current MSP members are highly reliable partners. Except for India, all fall into the low-risk category (scores above 140, see figure 5). One important challenge is that critical materials have complex supply chains with various extraction, refining, and processing locations. The simplest solution would be to work across the supply chain with countries such as Canada and Australia, which are both highly reliable and have large mining sectors. Where this is not possible, the MCR could be used to assess risk across supply chains. Going forward, the United States could leverage reliability ratings when assessing prospective projects and candidate countries for the MSP.

Microchips: The Chip 4 Alliance and Regional Initiatives. Semiconductors are essential for virtually all modern industrial products, from computers and smartphones to cars and refrigerators. Furthermore, they are critical enablers of technologies likely to shape the future, such as artificial intelligence, autonomous systems, and quantum computing.62 While American companies—such as AMD, Nvidia, and Qualcomm—are global leaders in designing advanced chips, they often rely on foreign-owned foundries outside the United States to manufacture their designs. In 2020, U.S.-headquartered companies owned 22 percent of global chip manufacturing capacity, but only 10 percent of chips were produced in the United States. As a result, the United States lagged other major chip-producing nations, namely China (22 percent of global chip production), Taiwan (18 percent), Japan (17 percent), and South Korea (16 percent).63

The microchip supply chain is characterized by unique risks to resilience and security. Producing chips is highly complex and requires huge investments in specialized facilities, machinery, and highly trained staff. TSMC and other Taiwanese companies make over 90 percent of cutting-edge logic chips, rendering this vital technology vulnerable to supply chain disruptions.64 Leading U.S. microchip companies have also significantly invested in supply chain infrastructure in China and are therefore concerned about the financial ramifications of disentanglement.65 In response, in August 2022, the U.S. Congress passed the CHIPS and Science Act, which aims to bolster chip production in the United States and provides $52.7 billion for semiconductor research, manufacturing, and workforce development.66

In addition to creating stronger incentives for domestic production, the United States initiated a semiconductor friend-shoring partnership: the Chip 4 Alliance. First proposed in March 2022, this partnership brings together four of the world’s largest semiconductor producers—Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and the United States. The alliance’s inaugural high-level meeting occurred in February 2023. Unlike the MSP, Chip 4 Alliance member states control large parts of the global semiconductor supply chain. Their leading microelectronics companies are one another’s top competitors. The Chip 4 Alliance aims to protect intellectual property, smartly coordinate trade guidelines, and promote supply chain resilience among members.67

The MCR framework is useful for assessing the current alliance and prospective partners. Japan (155) and South Korea (147) have high scores and therefore pose low risks. As noted earlier, Taiwan is not a UN member, and we conservatively estimate its MCR to be 94—a moderate risk level that reflects the island’s contested status. This suggests that excluding China from U.S. microchip supply chains would significantly reduce risks, specifically an MCR score increase from 39 (China) to 94 (Taiwan). This implies a decrease in supply chain risks from high to moderate levels if it is possible to circumvent China. Given the cascading costs of de-risking supply chains, however, China’s exclusion would likely have to be limited to high-end chips.

To further diversify supply chains and benefit more from global competition, the United States could capitalize on recent European investments in the microchip industry. The European Union (EU)’s 2023 Chips Act designates $47 billion to double its semiconductor market share by 2030. Microchip supply chains are also an increasingly important topic at the U.S.-EU Trade and Technology Council, a far-reaching economic forum established in 2021.68 The MCR could help to evaluate candidates for enhanced partnerships in Europe. For example, the United Kingdom (175), the Netherlands (166), and Germany (165) would be safe bets, and U.S. companies are exploring major investments in some of these countries.69

Efforts are also underway to expand microchip supply chains to Central and South America, funded by the CHIPS Act’s International Technology Security and Innovation (ITSI) Fund. Recent ITSI partnerships with Costa Rica (132), Panama (126), and Mexico (103) seek to expand assembly, testing, and packaging supply chains.70 These countries are not only nearer to home but also have fairly high MCR scores. In the Indo-Pacific region, ITSI partnerships have been established with the Philippines (94), Indonesia (82), and even Vietnam (46).71 As the United States seeks to diversify supply chains in the region, India (106) and Malaysia (82) could be promising candidates, too. In particular, Malaysia has already created an impressive micro-electronics manufacturing ecosystem.72 Thus, the MCR can guide the United States in de-risking critical aspects of the chip supply chain from China.

Conclusion

Growing geopolitical risks to global trade require new forms of international cooperation. Selecting economic partners strictly based on the logic of comparative advantage no longer seems sufficient for shock-proofing critical supply chains. Conversely, attempting to return all critical supply chains back to the United States would be either extremely costly or simply infeasible due to limited domestic resources, expertise, and infrastructure. Friend-shoring, then, is a policy alternative to mitigate supply chain risks, especially in the most critical sectors. However, it requires aligning policies and regulations with other countries and, in many cases, will still result in higher costs. Hence, getting the selection of partners right is crucial for the success of any friend-shoring initiative.

This article introduced a simple, transparent, globally applicable measure to score the reliability of countries—the MCR—and applied it to a historical example: the successful U.S. efforts to re- duce reliance on oil imports from OPEC states after the traumatic experience of the 1973 oil embargo. Next, it applied the MCR to friend-shoring initiatives on critical minerals and microchips, illustrating that working with partner nations in these areas could result in more resilient and secure supply chains.

The MCR offers scholars and practitioners of economic and national security policy a systematic starting point for an in-depth analysis of new markets for investments and could thus promote stronger economic alliances. Current and future friend-shoring efforts could use the MCR to gauge political risks across the entirety of their supply chains and evaluate potential partners. The measure might be- come even more important as the United States expands friend-shoring to other critical sectors, including biotechnology. Future friend-shoring initiatives would benefit from incorporating the MCR framework into their risk assessments and thereby prevent attempts to weaponize economic interdependence. JFQ

Notes

1 From 1990 to 2015, the number of people living in extreme poverty (below $1.90 per person per day) fell from 1.9 billion to 729 million. See Homi Kharas and Meagan Dooley, The Evolution of Global Poverty, 1990–2030, Brookings Global Working Paper #166 (Washington, DC: Center for Sustainable Development at Brookings, February 2022), 6, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Evolution-of-global-poverty.pdf.

2 Daniel W. Drezner et al., eds., The Uses and Abuses of Weaponized Interdependence (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, March 2021).

3 “G7 Hiroshima Leaders’ Communiqué,” Council of the European Union, May 20, 2023, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2023/05/20/g7-hiroshima-leaders-communique/.

4 “What Is ‘Friendshoring’?” The Economist, August 30, 2023, https://www.economist. com/the-economist-explains/2023/08/30/what-is-friendshoring.

5 Prepared Statement of Treasury Secretary Designee Scott Bessent, U.S. Senate Committee on Finance, January 16, 2025, https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/1162025_bessent.pdf.

6 “Marco Rubio: An Americas First Foreign Policy,” U.S. Embassy Bogota, January 31, 2025, https://co.usembassy.gov/marco-rubio-an-americas-first-foreign-policy.

7 Raghuram G. Rajan, “Just Say No to Friend-Shoring,” Project Syndicate, June 3, 2022, https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/friend-shoring-higher-costs-and-more-conflict-without-resilience-by-raghuram-rajan-2022-06.

8 David Leonhardt, “A Subtle Change for Biden,” New York Times, September 20, 2023.

9 “Remarks by Secretary of the Treasury Janet L. Yellen on Way Forward for the Global Economy,” Department of the Treasury, April 13, 2022, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0714.

10 Michael A. Bailey et al., “Estimating Dynamic State Preferences From United Nations Voting Data,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 61,mno. 2 (February 2017), 430–56, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002715595700.

11 Mark J.C. Crescenzi et al., “Reliability, Reputation, and Alliance Formation,” International Studies Quarterly 56, no. 2 (June 2012), 259–74, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1450539.

12 Brett Ashley Leeds and Michaela Mattes, JFQ 117, 2nd Quarter 2025 Domestic Interests, Democracy, and Foreign Policy Change (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2022).

13 Eugenio Cerutti et al., “The Impact of U.S.-China Trade Tensions,” IMF Blog, May 23, 2019, https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2019/05/23/blog-the-impact-of-us-china-trade-tensions.

14 Elaine Dezenski and John C. Austin, “Rebuilding America’s Economy and Foreign Policy With ‘Ally-Shoring,’” Brookings, June 8, 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/rebuilding-americas-economy-and-foreign-policy-with-ally-shoring/.

15 “Transcript of Fireside Chat of U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet L. Yellen and Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance Chrystia Freeland Hosted by Canada 2020,” Department of the Treasury, June 20, 2022, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0830.

16 Emily Tamkin, “The New Geopolitical Vocabulary,” Foreign Policy, December 30, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/12/30/new-geopolitics-vocabulary-popular-buzzwords-2022/.

17 Emily Benson and Ethan B. Kapstein, “The Limits of ‘Friend-Shoring,’” Center for Strategic and International Studies, February 2023, https://www.csis.org/analysis/limits-friend-shoring.

18 Beata S. Javorcik et al., Economic Costs of Friend-Shoring, CESifo Working Paper No. 10869 (Munich: Munich Society for the Promotion of Economic Research, December 2023), 5, https://www.cesifo.org/en/publications/2023/working-paper/economic-costs-friend-shoring.

19 On the negative economic effects of supply chain disruptions, see Xiwen Bai et al., The Causal Effects of Global Supply Chain Disruptions on Macroeconomic Outcomes: Evidence and Theory (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, February 2024), https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w32098/w32098.pdf.

20 Patrick Porter and Joshua Shifrinson, “Why We Can’t Be Friends With Our Allies,” Politico Magazine, October 22, 2020, https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2020/10/22/why-we-cant-be-friends-with-our-allies-431015.

21 André Broome, “Doing Business: How Countries Gamed the World Bank’s Business Rankings,” LSE British Politics and Policy, January 6, 2022, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/world-bank-business-rankings/.

22 On military alliances, see Iain D. Henry, “What Allies Want: Reconsidering Loyalty, Reliability, and Alliance Interdependence,” International Security 44, no. 4 (2020), 45–83, https://direct.mit.edu/isec/article/44/4/45/12250/What-Allies-Want-Reconsidering-Loyalty-Reliability. On corporate alliances, see Oliver Schilke and Karen S. Cook, “Sources of Alliance Partner Trustworthiness: Integrating Calculative and Relational Perspectives,” Strategic Management Journal 36, no. 2 (2015), 276–97, https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2208.

23 On the synergies between international relations theory and organizational science, see Rafael Biermann and Michael Harsch, “Resource Dependence Theory,” in Palgrave Handbook of Inter-Organizational Relations in World Politics, ed. Rafael Biermann and Joachim A. Koops (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 135–55.

24 Alex Weisiger and Keren Yarhi-Milo, “Revisiting Reputation: How Past Actions Matter in International Politics,” International Organization 69, no. 2 (Spring 2015), 473–95, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818314000393.

25 Brett Ashley Leeds, “Alliance Reliability in Times of War: Explaining State Decisions to Violate Treaties,” International Organization 57, no. 4 (Autumn 2003), 801–27, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818303574057; Neil Narang and Brad L. LeVeck, “International Reputation and Alliance Portfolios: How Unreliability Affects the Structure and Composition of Alliance Treaties,” Journal of Peace Research 56, no. 3 (2019), 379–94, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343318808844.

26 James Raymond Vreeland and Axel Dreher, The Political Economy of the United Nations Security Council: Money and Influence (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

27 Javorcik, Economic Costs of Friend-Shoring.

28 Bailey et al., “Estimating Dynamic State Preferences From United Nations Voting Data,” 431.

29 G. John Ikenberry, After Victory: Institutions, Strategic Restraint, and the Rebuilding of Order After Major Wars (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001).

30 We use an average value to account for annual variation in the agenda of the UN General Assembly. However, we limit this average to the most recent 3 years because bilateral relations are dynamic, and the salience of past behavior typically decreases swiftly. See Crescenzi et al., “Reliability, Reputation, and Alliance Formation,” 264. If we use the 5- or 10-year average, the results are similar, though decreasingly reflective of countries’ current relationship with the United States.

31 Michaela Mattes et al., “Leadership Turnover and Foreign Policy Change: Societal Interests, Domestic Institutions, and Voting in the United Nations,” International Studies Quarterly 59, no. 2 (2015), 280–90, https://doi.org/10.1111/isqu.12175.

32 Matthew Kroenig, The Return of Great Power Rivalry: Democracy Versus Autocracy From the Ancient World to the U.S. and China (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020); G. John Ikenberry, “The Next Liberal Order,” Foreign Affairs 99 (July/August 2020), 133–42, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-06-09/next-liberal-order.

33 Charles Lipson, Reliable Partners: How Democracies Have Made a Separate Peace (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003).

34 Leeds and Mattes, Domestic Interests, Democracy, and Foreign Policy Change.

35 Brett Ashley Leeds et al., “Interests, Institutions, and the Reliability of International Commitments,” American Journal of Political Science 53, no. 2 (April 2009), 461–76, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00381.x.

36 We convert older scores of 1 to 7 (1–2.5= “free,” 3–5 = “partly free,” and 5.5–7 = “not free”) to a 100-point scale.

37 For details, see “Countries and Territories,” Freedom House, n.d., https://freedomhouse.org/countries/freedom-world/scores.

38 Chris Miller, Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology (New York: Scribner, 2022).

39 One alternative is to assume that Taiwan’s voting behavior would resemble that of a UN member state in the same region with similar gross domestic product per capita and close ties to the United States, such as South Korea. However, this optimistic assumption would result in a very high MCR for Taiwan, which does not seem to reflect the involved risks accurately. Thus, we err here on the side of caution by using a score at the low end.

40 Mohammed E. Ahrari, OPEC: The Failing Giant (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1986), 92.

41 Both the surprise nature of the attack and the fact that the indicators used for the MCR predate the October 1973 crisis reduce concerns about reverse causality. Specifically, Freedom House’s 1973 scores cover the year 1972 and were published in the January/February 1973 issue of the journal Freedom at Issue. United Nations voting ideal points are based on the General Assembly’s regular sessions, which begin each year in the third week of September. The voting data used in figure 3 hence covers the period from September 1970 to September 1973.

42 Jeff D. Colgan, “The Emperor Has No Clothes: The Limits of OPEC in the Global Oil Market,” International Organization 68, no. 3 (Summer 2014), 614, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818313000489.

43 Ahrari, OPEC, 74.

44 The inflation-adjusted gas pump price (constant 2015 dollars per gallon) increased from $1.62 in 1973 to $2.03 in 1974, and from $2.31 in 1979 to $2.95 in 1980. See “Fact #915: March 7, 2016, Average Historical Annual Gasoline Pump Price, 1929–2015,” Department of Energy, https://www.energy.gov/eere/vehicles/fact-915-march-7-2016-average-historical-annual-gasoline-pump-price-1929-2015.

45 Tamara Nemeth and Stephen J. Randall, “The 1970s Arab-OPEC Oil Embargo and Latin America,” H-Energy, 2013.

46 “Oil and Petroleum Products Explained,” Energy Information Administration, January 19, 2024, https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/oil-and-petroleum-products/imports-and-exports.php.

47 “Petroleum and Other Liquids: Data,”Energy Information Administration, January 31, 2025, https://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/pet_move_impcus_a2_nus_epc0_im0_mbbl_m.htm.

48 Chris Isidore, “One Year Into Ukraine War, U.S. Gas Prices Are Lower. Here’s What to Expect Ahead,” CNN, February 25, 2023, https://www.cnn.com/2023/02/25/energy/us-gas-prices-one-year-after-invasion/index.html.

49 Building Resilient Supply Chains, Revitalizing American Manufacturing, and Fostering Broad-Based Growth, 100-Day Reviews Under Executive Order 14017 (Washington, DC: The White House, June 2021), 4, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GOVPUB-PR-PURL-gpo156599/pdf/GOVPUB-PR-PURL-gpo156599.pdf.

50 Building Resilient Supply Chains, Revitalizing American Manufacturing, and Fostering Broad-Based Growth, 154.

51 Building Resilient Supply Chains, Revitalizing American Manufacturing, and Fostering Broad-Based Growth, 159.

52 “Ambassador Katherine Tai’s Remarks at the National Press Club on Supply Chain Resilience,” Office of the United States Trade Representative, June 15, 2023, https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/speeches-and-remarks/2023/june/ambassador-katherine-tais-remarks-national-press-club-supply-chain-resilience.

53 Marco Rubio, “Congress Must Act on a Bipartisan Solution to our Critical Minerals Crisis,” The Hill, August 9, 2024, https://thehill.com/opinion/4817683-critical-minerals-crisis-china.

54 “What Is Vanadium?” AustralianVanadium Limited, n.d., https://www.australianvanadium.com.au/what-is-vanadium/.

55 George J. Simandl and Suzanne Paradis, “Vanadium as a Critical Material: Economic Geology With Emphasis on Market and the Main Deposit Types,” Applied Earth Science 131, no. 4 (2022), 218–36, https://doi.org/10.1080/25726838.2022.2102883.

56 “China Controls the Supply of Crucial War Minerals,” The Economist, July 13, 2023, https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2023/07/13/china-controls-the-supply-of-crucial-war-minerals.

57 Building Resilient Supply Chains, Revitalizing American Manufacturing, and Fostering Broad-Based Growth, 176.

58 Ming Hwa Ting and John Seaman, “Rare Earths: Future Elements of Conflict in Asia?” Asian Studies Review 37, no. 2 (2013), 240.

59 Vlado Vivoda, “Friend-Shoring and Critical Minerals: Exploring the Role of the Minerals Security Partnership,” Energy Research & Social Science 100 (June 2023), 5, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2023.103085.

60 “Minerals Security Partnership,” Department of State, n.d., https://www.state.gov/minerals-security-partnership/.

61 “Joint Statement of the Minerals Security Partnership,” Department of State, March 4, 2024, https://2021-2025.state.gov/joint-statement-of-the-minerals-security-partnership/.

62 Alice B. Grossman et al., Semiconductors and the Semiconductor Industry, R47508 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, April 19, 2023), 1, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/r/r47508.

63 Grossman et al., Semiconductors and the Semiconductor Industry, 9.

64 Building Resilient Supply Chains, Revitalizing American Manufacturing, and Fostering Broad-Based Growth, 12.

65 Christian Davis et al., “U.S. Struggles to Mobilise Its East Asian ‘Chip 4’ Alliance,” Financial Times, September 12, 2022.

66 “CHIPS and Science Act Will Lower Costs, Create Jobs, Strengthen Supply Chains, and Counter China,” The White House, August 9, 2022, https://web.archive.org/web/20250117232249/https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/08/09/fact-sheet-chips-and-science-act-will-lower-costs-create-jobs-strengthen-supply-chains-and-counter-china/.

67 Emily Benson et al., “Securing Semiconductor Supply Chains in the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, May 2023, 5, https://www.csis.org/analysis/securing-semiconductor-supply-chains-indo-pacific-economic-framework-prosperity.

68 Emily Benson et al., “Transatlantic Cooperation on Semiconductors and AI in 2024,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, January 17, 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/transatlantic-cooperation-semiconductors-and-ai-2024.

69 Sujai Shivakumar et al., “A World of Chips Acts: The Future of U.S.-EU Semiconductor Collaboration,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, August 20, 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/world-chips-acts-future-us-eu-semiconductor-collaboration.

70 The State Department announced the partnerships with Costa Rica and Panama in July 2023 and the one with Mexico in March 2024. See “The U.S. Department of State International Technology Security and Innovation Fund,” n.d., https://www.state.gov/the-u-s-department-of-state-international-technology-security-and-innovation-fund/.

71 The State Department announced the partnership with Vietnam in September 2023 and partnerships with the Philippines and Indonesia in November 2024. See “The U.S. Department of State International Technology Security and Innovation Fund.”

72 Patricia Cohen, “Malaysia Rises as Crucial Link in Chip Supply Chain,” New York Times, March 13, 2024.