Download PDF

Dr. F.G. Hoffman is a Distinguished Research Fellow in the Center for Strategic Research, Institute for National Strategic Studies, at the National Defense University.

There is not a single discrete future out there in the time to come. Instead there are almost certainly an unknowable number of possible futures. . . . The past is singular . . . the future, in sharpest contrast, assuredly plural.

—Colin Gray

The formulation of sound strategy is inherently tied to the art of forecasting. Rather than precise predications, any sound strategy has to be founded on embracing uncertainty, assessing risk, and testing hypotheses.1 This may be particularly true for defense strategies. Multidimensional challenges, like crafting a long-term defense strategy, cannot rely on dartboards or algorithms fed by Big Data. As RAND’s Michael Mazarr has perceptively noted, this is not the nature of the big national security challenges. “These are value-based judgment calls or one-off issues,” he has concluded, “where data and patterns will offer very limited guidance.”2 The central question for senior leaders in defense is improving their assessment of risk in ambiguous contexts.

Marine provides tactical navigation assistance to pilots in UH-Y Huey helicopter embarked aboard USS Green Bay, during amphibious raid rehearsal as part of Talisman Saber 17, Coral Sea, July 8, 2017 (U.S. Navy/Sarah Myers)

This article examines the use of scenarios to enhance the development of defense strategy and explores three critical uncertainties that will frame a number of potential futures for U.S. security strategy to demonstrate the utility and application of effective scenario use.

A sound strategy process is not, or at least should not be, an exercise in eliminating uncertainty and making smart choices based on a clear-cut prediction. This is not an advisable approach since our grasp of the future is so tenuous. As Colin Gray once advised the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), any strategy starts with the recognition that its authors will be surprised many times in the future. The key is not to be disabled by the effects of surprise—we should plan with the intent of creating capabilities and consequences that are surprise-tolerant. The goal in prudent defense planning is to avoid optimization for one world, to plan flexibly, adaptively, and inclusively.3 To posture an institution for the breadth of challenges for which adaptation may be necessary, we have to open up the aperture to potential futures via scenarios posited to test how inclusive or responsive our plans are.

History is not irrelevant when exploring the future. The challenge is to remain engaged with the past but to unshackle leaders from the worst kind of confirmation bias, which assumes that since the future is unknowable, it will be based on what we now know.4 Instead of searching for the unknowable Black Swan, smart planners should stop avoiding inconvenient trends that disturb organizational preferences with new challenges and orphan missions, which some call Pink Flamingos.5

Large institutions, including the Armed Forces, tend to think about the future in linear and evolutionary steps and make implicit assumptions about the next war as merely an extension of the last. This results in strategic and operational surprise. Yet most surprises, as Peter Schwartz has long noted, do not spring forth from unexpected consequences but rather from group denial.6 Most international shocks were envisioned by someone, warned about, but resolutely ignored. Instead of grasping new contexts or potential circumstances that alter our understanding, we tend to project trends as linear plots. In retrospect, after a strategic shock, we prefer to construct a script about how signals and vague omens were lost in the noise. In reality, the signals were drowned by leaders who turned up the volume on comfortable preferences.

This is where scenario-based planning comes into play, to break out of rigid mental frames and open up a discourse among senior leaders about trends, assumptions, and potential shocks.7 Scenarios and multiple futures help policymakers foresee possible inflection points and bring uncertainty into account. Scenario-based analysis facilitates the incorporation of critical drivers and trends that might fundamentally change the future environment in significant ways. By identifying key trends and drivers along a plausible alternative path, from the present to different futures, scenarios can “help Pentagon leaders avoid the ‘default’ picture by which tomorrow looks very much like today.”8

Scenarios, properly employed, can help reduce some of the critical influences of uncertainty and friction in strategy formulation. In particular, in the diagnosis and formulation phases of strategy development, scenarios can sharpen the diagnosis as well as shape options for tradeoffs in strategy options and formulation. Without scenarios, strategists may pursue bureaucratically favored solutions masked as operative strategies. With scenarios, the same strategy team may have a better feel for how its biases and preferred solutions create risks in different worlds.

As noted, good strategy is ultimately an art that employs forecasting, risk management, and the testing of hypotheses. Good forecasters, including so-called Super Forecasters, are more scrupulous about their personal biases and tend to become more empirical in their assessments to try to avoid a lack of objectivity.9 This empiricism is a learned skill as is the use of good trend analysis and scenarios. These are the tools that every strategist should embrace.

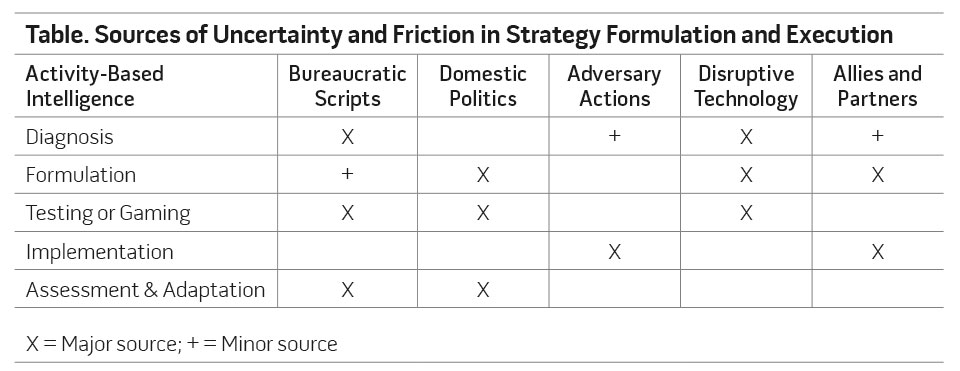

There are many sources of uncertainty in strategy, and they can occur at different times in the strategy formulation process. They do not have to serve solely as illustrations or explain a future environment.10 The table depicts a summary of potential sources of uncertainty and friction in the strategy formulation and execution process.11 The first column details the basic steps in strategy development, to include the need to assess and adapt strategies in action. The first row lays out potential sources of both uncertainty and friction that may impede an objective understanding of the environment, the framing of potential options, and decisionmaking. These include both internal (like bureaucratic resistance or internal scripts) and external (the opponent being the most obvious) sources.12 Good scenario testing can be an effective counter to that, perhaps by a Red Team, to challenge strategy group think. Red Teaming has recently been emphasized as an important tool in helping decisionmakers better understand the vulnerabilities of a given course of action.13 The evaluation of effective strategies, ones that can adequately respond to the world as it is rather than an imaginary or preferred world, is a critical part of the strategy development process. Strategy testing against scenarios helps both the decisionmaker and strategy team by exploring consequences of seemingly favorable strategic plans. There are risks in inaction as well as unintended or unforeseen costs in preferred options. As Michael Mazarr has noted in his study of risk analysis preceding the 2008 financial crisis, “the most profound risk disasters in finance and national security come from insufficient attention to and awareness of the potential risky consequences of intended or favored strategies.”14

Bureaucracies, including planning cells in institutions like the Department of Defense, tend to make their outlook of the future match up well with their preferred solutions. Scenarios provide a less threatening way to lay out alternative futures in which the bias, preferences, and assumptions underpinning today’s strategy may no longer be true. This can help avoid groupthink.15 Decisionmakers should temper that possibility with astute use of scenarios founded upon the critical assumptions or uncertainties that will impact their enterprise the most.16

Some analysts believe that uncertainty gets too much credit and contributes to negative influences in the development of U.S. defense strategy. One analyst goes so far as to claim that defense planners over-privilege uncertainty, which retards difficult choices that can and must be made. Based on an assessment of the quality of the analysis supporting the Defense Department’s Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR) in 2010, Mark Fitzsimmons concluded that “Creative, unbounded speculation must resolve to choice or else there will be no strategy. Recent history suggests that unchecked skepticism regarding the validity of prediction can marginalize analysis, trade significant cost for ambiguous benefit, empower parochial interests in decision-making, and undermine flexibility.”17 This reflects an erroneous belief that prediction is necessary to make decisions and tradeoffs. In reality, this is more of a gamble than a strategic method. It surely undermines flexibility for responding to what cannot be known with any reliable detail.

While the 2010 QDR may have been perceived as embracing uncertainty (and was overly optimistic about resources), a better case study is the Defense Strategy Guidance of 2012. Every assumption made by the Barack Obama administration and accepted by Secretary of Defense Robert Gates and the Pentagon at that time (Russia, benign; China, not assertive; Sunnis, contented) all proved completely wrong. Crimea, Ukraine, the South China Sea, and the so-called Islamic State’s nova certainly ended the notion that narrow prediction was a good bet. It turns out that the creative speculation was blind faith in prediction, unbounded by any appreciation for what might happen. In this case, employing scenarios might have produced a more informed choice, one that expands rather than marginalizes analysis. Forecasting intelligently, as well as understanding the probabilities and potential implications, are more important for long-range strategies than a prediction.

Scenarios help resolve an inherent tension in formulating strategy. Professor Hal Brands of the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies observes that strategy is beset with tensions including “between the need for foresight and the fact of uncertainty; between the steadiness and purpose that are necessary to plan ahead, and the agility that is required to adapt on the fly.”18 That tension, between foresight and inherent uncertainty, is the Holy Grail of sound strategy.

But while scenarios provide a good way of evaluating strategies, the scenarios themselves do not generate the strategy. As Richard Danzig has noted, “the propagation of scenarios, however sophisticated, broad ranging or insightful, does not obviate the need for strategies for coping with uncertainty.”19 The scenarios are a mechanism for that since they are plausible contexts a strategy may have to face, and for which responsible policymakers may have to prepare for or hedge against.

Critical Uncertainties

In this article, three critical uncertainties are selected that the author contends will significantly shape the context for the execution of U.S. policy and defense strategy over the next one to two decades.20 There are many relevant megatrends that will impact our future.21 Several of these can be bundled together into uncertainties for which there is a plausible path and for which assumptions are perilous. If these three uncertainties are taken out in time to their natural conclusion or a plausible alternative future, existing U.S. national security strategies would have to be adapted, possibly in “ways and means” that we are currently unprepared to recognize or accept.

These uncertainties are geopolitical competition from major rivals, U.S. economic performance, and alliance cohesion and capacity.

Geopolitical Competition from Major Rivals. This driver poses a polarity between a highly collaborative world order largely within the extant rules-based international system that exists today. It may be adapted to better reflect post–Cold War adjustments in national power. At the other end of the uncertainty factor is the existence of a conflict-ridden environment of great power competition.22 Such a world would be based on the collapse of many norms and values, a possible rejection of international mechanisms to mitigate direct confrontation in the economic or security domains, and the rising potential for direct military conflict inside the established spheres of influence of the major powers. This is a future of substantially higher risk of confrontation in which current force development plans would leave the joint force outmatched in key dimensions of future war.

Trend lines in this driver are ominous. Russia’s announced defense spending is slated to rise 44 percent over the next 3 years, the largest increase of any state.23 China’s significant economic development and rapid military modernization could conceivably produce circumstances in which great power competition erupts into a war.24 Already, Chinese military modernization shows great progress in offsetting U.S. power projection capabilities.25 Scholars of rising powers and transition periods show that periods marked “by hegemonic decline and the simultaneous emergence of new great powers have been unstable and prone to war.”26 As Harvard’s Graham Allison has noted, the emergence of rising powers has resulted in war with existing powers in 12 of 16 cases.27

At the upper range of this driver, we could foresee a world in which the world order was in complete disarray, and in which China and Russia would be aligned against the democratic and open liberal order.28

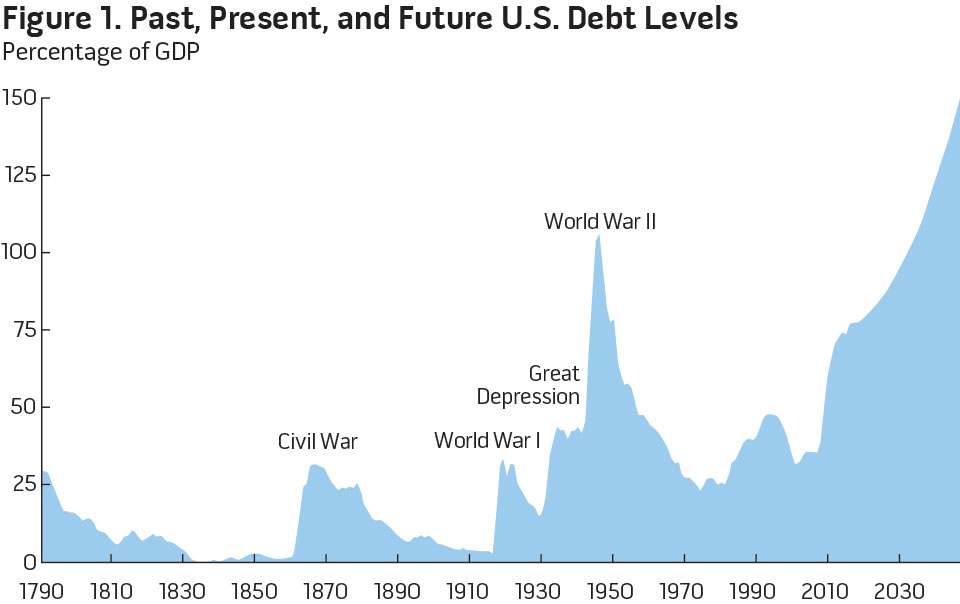

U.S. Economic Performance. This driver captures the potential range of U.S. domestic economic performance ranging from high growth rates in excess of 3 percent at one end and flat or slightly declining economic performance at the other. The negative end of this trend would be predicated on continued political polarization in the country, as well as continued gridlock on Federal budget reforms to tame spiraling income security and healthcare costs. Under this scenario, entitlement costs and interest payments by 2030 consume 85 percent of the Federal budget and the Federal debt climbs to 150 percent of gross domestic product (GDP).

The U.S. economy grew by an average of 3.8 percent from 1946 to 1973, while real median household income surged 74 percent (or 2.1 percent a year). But real GDP (accounting for inflation) grew by only an average of 1.7 percent from 2000 to the first half of 2014, a rate around half the historical average. Median income for middle-class Americans was flat for the past 20 years, although a distinct uptick of 5.2 percent growth recently occurred.29

Projections for U.S. economic growth are slightly higher in the next few years (1.9 to 2.2 percent). These projections will be influenced by numerous variables including U.S. tax policies, infrastructure investments, potential health policy changes, reform of government entitlement programs, and how well the U.S. economy adapts to numerous technological breakthroughs. However, the biggest challenge facing the future U.S. economy is reflected in its growing debt and interest payments required to pay for this financing of the U.S. Government.

The growth and resulting increase in mandatory interest payments is equally significant and may impinge on national economic growth and negatively impact resources for required Federal activity, including national defense. The U.S. public debt was $909 billion in 1980, an amount equal to 33 percent of America’s GDP. That number had more than tripled to $3.2 trillion—or 56 percent of GDP—by 1990. Total Federal debt (including debt held by the public and foreign countries and the Federal Reserve Bank) now exceeds $18 trillion and approaches 100 percent of GDP. It will climb over $20 trillion in the next 5 years and is projected to be greater than $24 trillion by fiscal year 2029 under current law. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that our interest payments will exceed $700 billion a year in 2027, up from $202 billion in 2009. This would represent a tipping point, as interest costs would exceed funding for the Department of Defense.

Figure 1 shows the historical track of publicly held Federal debt as a percentage of our gross economic capacity. The figure also shows how major conflicts have resulted in prior debt surges and reflects CBO projections for sharply higher debt levels, largely as a result of the retirement of the Baby Boomer generation.

A scenario of potentially significant risk would be one in which U.S. debt-carrying costs were to increase significantly, which would increase required interest payments. This is why Admiral Mike Mullen, former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, once claimed that the greatest threat to U.S. security was Federal debt levels.30 If interest costs simply returned to their norms—higher than 4 percent—our debt-servicing costs could rise by $4.4 trillion over the next decade.31 This would be a future in which our current strategy and forward posture would be unsustainable.

Alliance Cohesion and Capacity. This driver examines the assumptions and trends related to our current alliance system. That system uses national advantage as a source of access and influence in key regions of the world. The U.S. alliance system is a source of capability that augments the joint force and is a collective mechanism for maintaining international norms and values. The bases in Asia, Europe, and elsewhere that are made available by this network of partners hold immense value to U.S. global power projection and for conventional deterrence.

At one end of this factor we might assume a highly cohesive suite of capable allies and an extended network of partners that are politically and militarily strong enough to export hard military power beyond their borders. They would have robust conventional capability, enough to contribute to NATO’s immediate borders, as an example.

In this world, regional forces would be supported by over 2 percent of their collective GDP and have sufficient modernization funding to stay interoperable with U.S. forces. At the other end of the driver, our allies would be politically weak, demographically challenged by aging populations, and economically frozen by poor productivity levels and tepid trade. At the end of the decade, these countries would be investing 1.25 percent of their GDP to defense spending but have little expeditionary capability at all. These allies might cling to NATO but not contribute anything to its hard power.

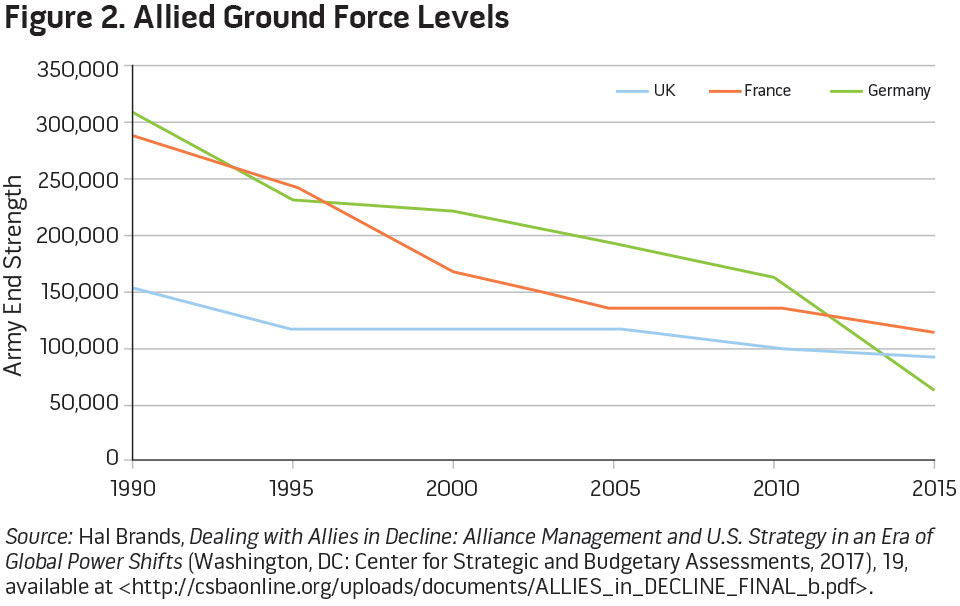

Trends are not favorable at present. Europe faces a future that observers believe could fragment its integration via a “perfect storm.”32 Given low economic productivity, aging demographics, and internal security needs, many NATO members have sharply reduced defense spending and could become more domestically oriented against internal security challenges.33 Prospects for increasing defense spending or collective defense appear to be diminishing.34 As seen in figure 2, the ground forces of our major partners in Europe have been in decline for some time.

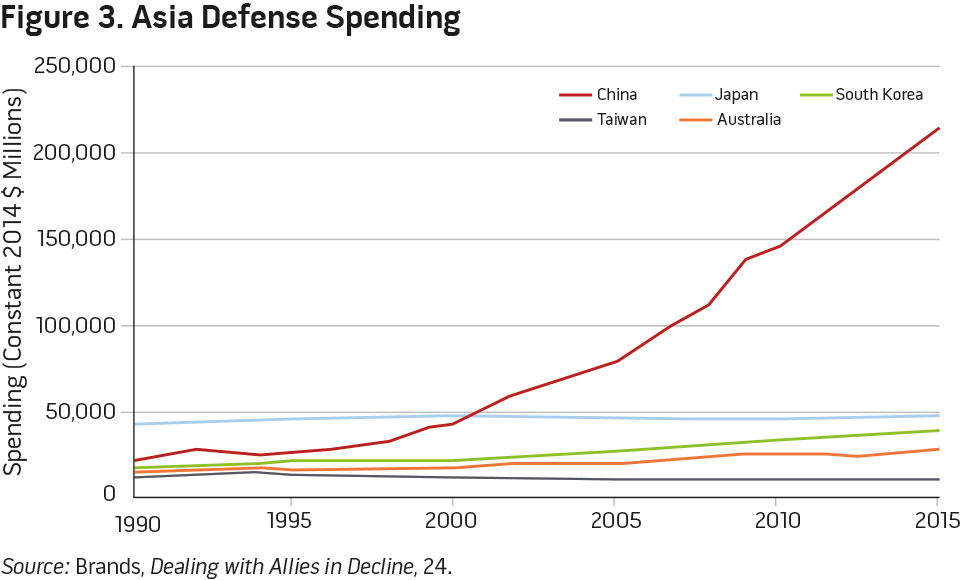

In Asia, some of the same challenges exist. Japan is aging rapidly and its defense spending represents only 5 percent of its national budget, or 1 percent of GDP.35 Japan’s debt is already at 245 percent of its annual GDP. Overall defense spending by current U.S. allies is stable but increasingly irrelevant given the large increases allocated to China’s People’s Liberation Army. If current trends continue, as regional defense spending suggests in figure 3, Asian security will be overshadowed by China.36

Multiple Futures

These significant uncertainties are not the only drivers of the future, but they arguably are the most stressing to the positon the United States would prefer to operate from. Over two decades ago, the U.S. economy was generating a surplus and growing at 3.5 percent annually, our debt was 33 percent of GDP, and NATO stood as history’s greatest alliance. We found ourselves in a unique positon, a unipolar moment that turned out to be just a moment in time.37 The challenge today is to secure the Nation’s core interests and obligations in the world as it is, not as we wish it to be.

Of course, there are other trends in the security environment, including global economic integration, technological diffusion, and both global and domestic income equality. All of these are certainly influential, but for the purpose of this intellectual exercise, not as critical to future U.S. defense choices as those we have discussed thus far.

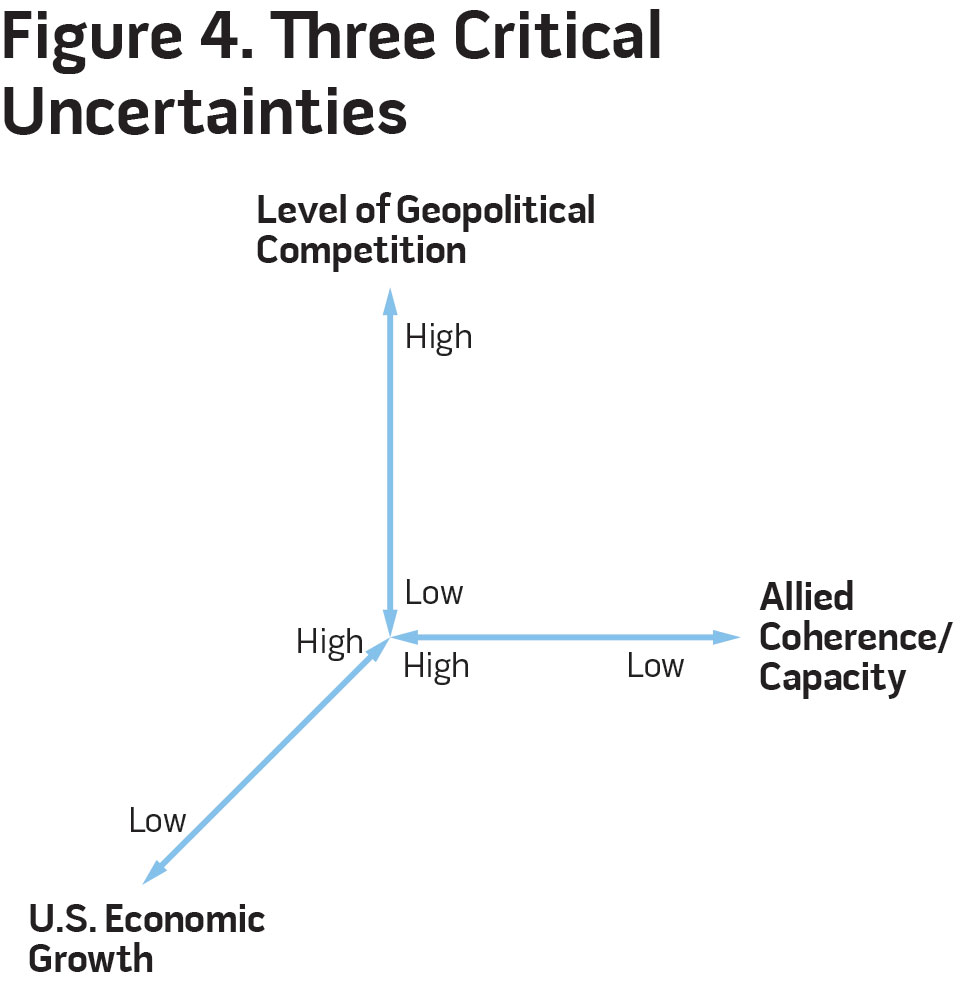

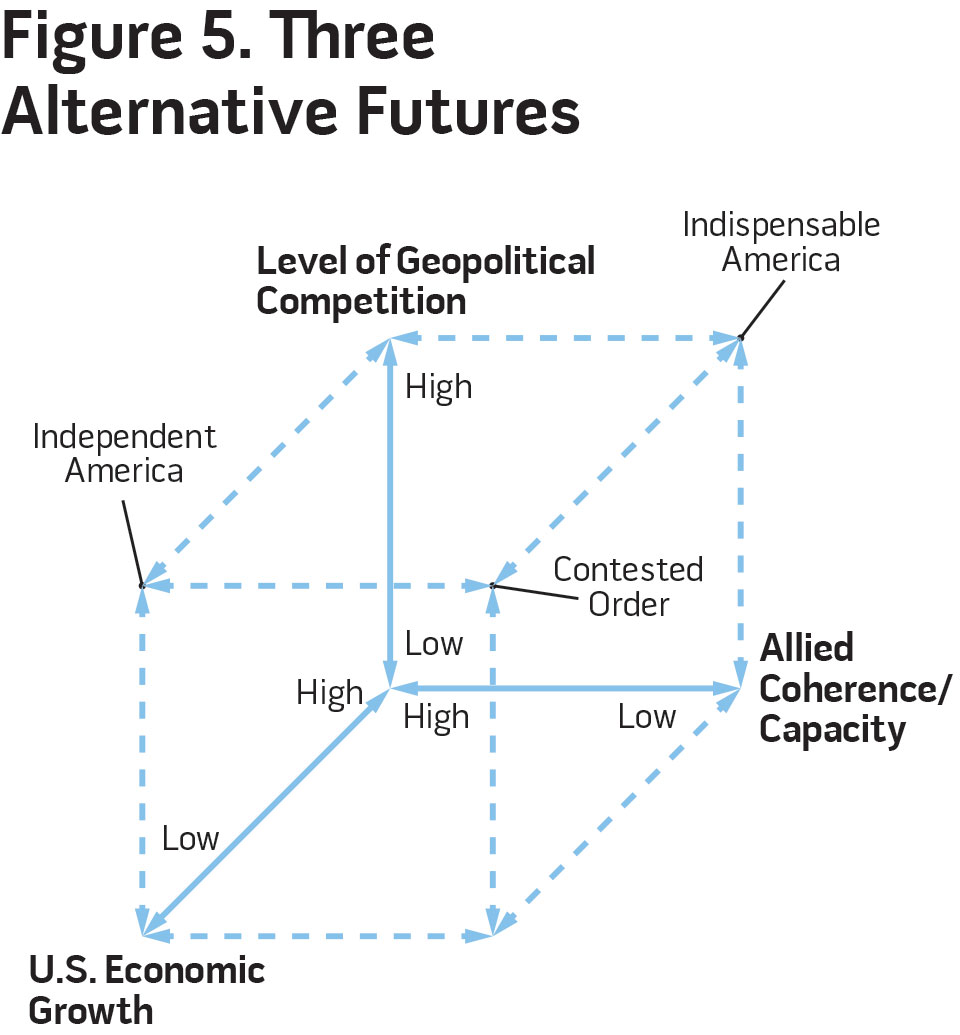

If we were to plot the identified drivers along three axes, it produces a future options space as depicted in figure 4. Each driver has potential signposts or stages that signal evidence of how each bundle of trends is emerging. The intersecting points, the antinodes, of these drivers produce options of potential future worlds we may live in, as depicted in figure 5. The corners that have been selected represent plausible alternative worlds if trends played out negatively for U.S. interests.

The Base Scenario world is where the three drivers intersect in a best-case world—one in which China and Russia were not competitive with the West, U.S. economic growth was 3 percent, and our allies and partners were highly capable and committed to the current international order. This may be the desired outcome of a potential grand strategy. Less desirably, combinations of the three critical uncertainties produce darker alternatives that are depicted and described below. The development of any robust national security strategy or a U.S. defense strategy should be tested against these worlds.

Indispensable America. This alternative future reflects the potential combination of rising revisionist powers (an entente between China and Russia) and a weakened international order with a much-weakened Western alliance structure that offers little combat capability and fewer bases for U.S. forward-deployed forces.38 Weaker allies will pose considerable challenges for U.S. security strategy over the next few decades. As Professor Brands has noted:

Regional military balances are shifting adversely as allies decline relative to their regional competitors, making America’s traditional responsibility as guarantor of stability and security in Europe and East Asia more difficult to uphold. In the event conflict occurs, the United States will face even greater challenges in defending its increasingly overmatched allies in these regions.39

In such a world, a greater burden to sustain a rules-based, liberal order would have to depend on the United States, making it literally “indispensable.”40

Independent America. This plausible extension of trends depicts a world in which U.S. economic performance has weakened and a greater share of the economic output of the country is spent on domestic needs, especially health care and income security, despite the rising global reach and power of contending peer competitors. With flat defense spending over the ensuing decade, U.S. security investments would be focused on securing the homeland first, with smaller numbers of much more sophisticated global strike systems to provide some conventional deterrence. The emphasis for U.S. national security strategy would be to preserve the Nation’s borders and domestic security. American leaders in this scenario would be tired of carrying NATO and its unwillingness to pay for its security and seek a more independent America free of burdensome and entangling coalitions.41

Contested Disorder. This future represents an extension of all three uncertainties to some degree. It posits an alternative future of poor U.S. economic performance under 1.5 percent growth, continued political division, and a constant erosion of U.S. security investments. Economic order is distressed due to the eruption of protectionist actions between the world’s two largest economies.42 At the same time, reduced alliance cohesion in Europe and in Asia diminishes U.S. interest and involvement with existing allies and partners. A majority of Americans in middle America do not agree that the cost of U.S. leadership is worth it.43 NATO may still exist in such a future, but its relevance and capacity are entirely rhetorical. Complicating this world is the continued encroachment of Russia along the periphery of Europe and deep penetration of the Old World’s governments and information institutions. Russia manages to continue its modernization.44 In Asia, China’s reach has expanded both in economic terms as every country’s major source of trade, economic growth, and investment. China’s economy has displaced America’s as the growth engine of the future.45

Marine fires AT-4 missile launcher during Exercise Platinum Eagle 17.2, at Babadag Training Area, Romania, May 3, 2017 (U.S. Marine Corps/Sarah N. Petrock)

Implications

The implications drawn from these different futures is not comforting—bigger enemies, fewer friends with diminished contributions, and a weakened government that has both less influence and a smaller iron fist behind its diplomacy. This is a more multipolar and chaotic world. With few shared values or institutions, it will be harder to manage and will require multiple compromises and sharp tradeoffs.46

The implications for the joint warfighting community are significant as well. A detailed analysis is beyond the scope of this article, but overall:

- A large-scale increase in U.S. military force size, as proposed by several key congressional leaders and think tanks, would be unsustainable in Independent America or Contested Disorder.47 The funding in a large buildup would be compounded by the resulting early outs/buy outs and ship decommissionings.

- A joint force that assumes access to foreign bases and counts on exportable combat power by an aging NATO or Cold War partnership may become a bad bet in Indispensable America. Since allies and partners constitute a major source of advantage, as the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs has publically emphasized, this strategic advantage may have to be discounted in assessing the future operating environment and military strategy.48 Certainly, over the last 15 years, despite concerns about burdensharing, the U.S. alliance system has proved to be material to U.S. global reach and power projection. The question for the future is how well the United States manages its alliance architecture and how political, social, and economic forces shape the contributory value of that system. This potential risk could be offset by working to build up partner capacity with existing or even new partners.49 Should this trend go completely negative, with Great Britain leaving both the European Union and NATO, for example, the United States might have to substantially alter its defense posture and pick up a heavier burden.

A smaller and less forward-deployed force would be extremely strained and at greater operational risk if tasked to sustain an open order overshadowed by China’s global power in Contested Disorder or even worse by a collective effort by the two major revisionist states. Designated spheres of influence would be accorded immediately to both of the revisionists who would continue to press against former U.S. allies, and eventually extract commercial advantages inimical to U.S. economic interests, employment, and prosperity. A world in which revisionist powers were collaborating and in which the extant international order was eroded and undefended would necessitate a significant shift in U.S. grand strategy and a higher order of defense spending and force buildup. Some argue that the major powers should reach an accommodation, an agreement on a new order. But the conditions for such a concert are rare and more difficult to obtain from revisionist and rising powers.50

These scenarios may not come to fruition, but signposts for the variables involved can be identified and tracked. More important, U.S. grand strategy should be tested against these potential worlds and incorporate some actions to increase the chances of our obtaining the base case. Our defense strategy can also be stressed by testing it against these three futures as well, to assess how resilient it is against potential environments that may evolve. A joint force design for a future U.S. military has to consider not only today’s canonical war plans but also the breadth of these potential futures in some way.51

Strategy is formed around a hypothesis, since all strategy is purposeful and must rely on a causal relationship that expects that discrete decisions and actions will generate desired effects.52 The use of scenarios can test that hypothesis to help “future proof” the strategy that is selected.53

Obviously, U.S. actions offer a powerful input as to how these scenarios might play out. They are not preordained, and U.S. actions or lack of action will contribute to which future evolves. These scenarios are not predictive, as they are designed principally to illuminate potential futures and to serve as a starting point for strategic discourse by responsible national leaders. They can help clarify the implications of trends, underscore major assumptions, and frame potential options about a world that we might have to adapt to.

Alternative futures help decisionmakers understand potential future contexts and their implications in order to draw out potential issues, enhance hypotheses, and lay out signposts to track which path is emerging. The discourse a leadership team has over multiple futures enhances its decisions, clarifies strategic options (investments, divestments, and hedging), and better prepares for future adaptation. Multiple futures are also helpful in testing the robustness and adaptability of a strategy. Using scenarios, we can test how well the strategy can adapt—and how much risk is assumed—if the assumptions change. If the risk is too high, then the strategy should be modified or contingency plans developed to mitigate the risks and make the strategy more robust.54

At the end of the day, strategy and planning are based on well-informed hypotheses, not prediction. Scenarios are a potent tool, properly designed and employed, but they are not strategy per se. They are a means to that end, a tool for Pentagon civilian leaders to ensure that tomorrow’s military is not entirely built on yesterday’s mental models. These models or internal scripts should be acknowledged if not entirely avoided.55

Airman with 6th Force Support Squadron at MacDill Air Force Base participates in 2017 OpenWERX Hackathon, sponsored by U.S. Special Operations Command (U.S. Air Force/Brandon Shapiro)

Conclusion

The making of strategy has always required an unsparing examination of the future with the paring away of institutional biases and the reduction of systemic blinders, and no small amount of intellectual digging to develop and test reasonable hypotheses.56 It also requires long-term thinking and imagination. In his opus Strategy: A History, Sir Lawrence Freedman observed, “Having a strategy suggests an ability to look up from the short term and the trivial to view the long term and the essential, to address causes rather than symptoms, to see woods rather than trees.”57 This technique forces decisionmakers to see the whole forest and to imagine its growth over time.

We may have to learn to live with strategic surprise, for the complexity of the world we live in is inescapable and the potential for disruption and nonlinear change appears to be rising. But complexity, disruption, and uncertainty are not novel circumstances, nor are they insurmountable challenges to sound strategy. Risk management is a complex strategic task and it is best to confront the systemic biases that can influence critical decisions.58

The current Army Chief of Staff has noted, “War tends to slaughter the sacred cows of tradition, of consensus, of group think, and myopia. The next war will be no different.”59 That may be true, but it is a costly way to approach strategy in a dangerous era. To preclude tradition-bound groupthink and consensus-based complacency, we need to better exploit scenario testing against those sacred cows. With proper use of multiple futures, they can be grilled slowly until well done. JFQ

Notes

1 Nigel Gould-Davies, “Seeing the Future: Power, Prediction and Organisation in an Age of Uncertainty,” International Affairs 93, no. 2 (March 2017), 445–454.

2 Michael J. Mazarr, “Fixes for Risk Assessment in Defense,” War on the Rocks, April 22, 2017, available at <https://warontherocks.com/2015/04/fixes-for-risk-assessment-in-defense/>.

3 Colin S. Gray, “Defence Planning, Surprise and Prediction,” presentation to the Multiple Future Conference, NATO Allied Command Transformation, Brussels, May 8, 2009.

4 Paul Cornish and Kingsley Donaldson, 2020: World of War (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 2017), 6.

5 Nassim Nicholas Taleb made the Black Swan a well-known metaphor (an unpredictable event of great impact) in his Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable (New York: Random House, 2010). See also Frank Hoffman, “Black Swans and Pink Flamingos: Five Principles for Force Design,” War on the Rocks, August 19, 2015, available at <https://warontherocks.com/2015/08/black-swans-and-pink-flamingos-five-principles-for-force-design/>.

6 Peter Schwartz, Inevitable Surprises: Thinking Ahead in a Time of Turbulence (New York: Avery, 2004), 6.

7 Peter Schwartz, The Art of the Long View: Planning for the Future in an Uncertain World (New York: Currency Doubleday, 1996).

8 Andrew F. Krepinevich, 7 Deadly Scenarios: A Military Futurist Explores War in the 21st Century (New York: Bantam, 2009), 14.

9 Philip E. Tetlock and Dan Gardner, Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction (New York: Random House, 2015).

10 For a recent example of how the National Intelligence Council (NIC) employs scenarios to help U.S. senior leaders, see Global Trends: Paradox of Progress (Washington, DC: NIC, January 2017), 39–49, available at <www.dni.gov/files/documents/nic/GT-Full-Report.pdf>.

11 I am indebted to Stephen Fruhling who inspired this table. See Stephan Fruhling, “Uncertainty, Forecasting and the Difficulty of Strategy,” Comparative Strategy 25, no. 1 (July 2006), 24–25.

12 I use the term script as a substitute for national or Service culture, more narrowly than Lawrence Freedman in Strategy: A History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 607–629.

13 For a practical understanding of Red Teaming in both military and commercial enterprises, see Micah Zenko, Red Team: How to Succeed by Thinking Like the Enemy (New York: Basic Books, 2014).

14 Michael J. Mazarr, Rethinking Risk in National Security: Lessons of the Financial Crisis for Risk Management (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 146.

15 Charles Roxburgh, “The Use and Abuse of Scenarios,” McKinsey Strategy and Corporate Finance, November 2009, available at <www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/the-use-and-abuse-of-scenarios>.

16 For an example of how scenarios can be used to assess an institutional force design, see Frank G. Hoffman and G.P. Garrett, Envisioning Strategic Options: Comparing Alternative Marine Corps Structures (Washington, DC: Center for a New American Security, 2014).

17 Michael Fitzsimmons, “The Problem of Uncertainty in Strategic Planning,” Survival 48, no. 4 (Winter 2006–2007), 144. Emphasis added.

18 Hal Brands, What Good Is Grand Strategy? Power and Purpose in American Statecraft from Harry S. Truman to George W. Bush (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2015), 193.

19 Richard Danzig, Driving in the Dark: Ten Propositions about Prediction and National Security (Washington, DC: Center for a New American Security, October 2011), 7. On how to address different layers of uncertainty, see Ionut C. Popescu, “Strategic Uncertainty, the Third Offset, and U.S. Grand Strategy,” Parameters 46, no. 4 (Winter 2016–2017), 69–79.

20 On scenario-building in general and critical uncertainties, see Schwartz, The Art of the Long View, 100–117.

21 Mathew J. Burrows, The Future Declassified: Megatrends That Will Undo the World Unless We Take Action (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2014).

22 Walter Russell Mead, “The Return of Geopolitics: The Revenge of the Revisionist Powers,” Foreign Affairs, May/June 2014.

23 Russian Military Power: Building a Military to Support Great Power Aspirations (Washington, DC: Defense Intelligence Agency, 2017).

24 On Chinese naval modernization, see Phillip C. Saunders et al., The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles (Washington, DC: NDU Press, 2011).

25 Eric Heginbotham et al., The U.S.-China Military Scorecard: Forces, Geography, and the Evolving Balance of Power, 1996–2017 (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2015); Roger Cliff, China’s Military Power: Assessing Current and Future Capabilities (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

26 Christopher Layne, “Sleepwalking with Beijing,” The National Interest, May/June 2015, 45.

27 Graham Allison, Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’ Trap? (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017).

28 Richard N. Haass, A World in Disarray: American Foreign Policy and the Crisis of the Old Order (New York: Penguin, 2017); Hal Brands and Eric Edelman, “The Upheaval,” The National Interest, July/August 2017, 30–40.

29 Binyamian Appelbaum, “U.S. Household Income Grew 5.2 Percent in 2015, Breaking Pattern of Stagnation,” New York Times, September 13, 2017, available at <www.nytimes.com/2016/09/14/business/economy/us-census-household-income-poverty-wealth-2015.html?_r=0>.

30 Ed O’Keefe, “Mullen, Despite Deal, Debt Still Poses a Risk to National Security,” Washington Post, August 2, 2011, A1.

31 Phil Gramm and Thomas Saving, “The Economic Headwinds Obama Set in Motion,” Wall Street Journal, May 2017.

32 Richard N. Haass, “Managing Europe’s Perfect Storm,” Project Syndicate, October 2, 2015, available at <www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/mitigating-refugee-impact-europe-by-richard-n—haass-2015-10?barrier=accessreg>.

33 Griff Witte, “Europe Reluctant to Boost Military Spending,” Washington Post, March 28, 2014, A9; Olivier de France, Defence Budgets in Europe: Downturn or U Turn? Issue Brief 12 (Paris: European Union Institute for Security Studies, May 15, 2015), available at <www.iss.europa.eu/sites/default/files/EUISSFiles/Brief_12_Defence_spending _in_Europe.pdf>.

34 A recent Pew poll suggests that public support for NATO is low. When it came to committing to upholding Article 5, 49 percent of respondents thought their country should not defend an Ally. See Judith Dempsey, “NATO’s Allies Won’t Fight for Article 5,” Strategic Europe blog, Carnegie Foundation, June 15, 2015, available at <http://carnegieeurope.eu/strategiceurope/?fa=60389>.

35 Yoichi Funabashi, “Japan’s Silver Pacifism,” The National Interest, January/February 2016, 25–31.

36 Hal Brands, Dealing with Allies in Decline: Alliance Management and U.S. Strategy in an Era of Global Power Shifts (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 2017), 21, available at <http://csbaonline.org/uploads /documents/ALLIES_in_DECLINE_FINAL_b.pdf>.

37 Charles Krauthammer, “The Unipolar Moment Revisited,” The National Interest, Winter 2002/2003, available at <http://nationalinterest.org/article/the-unipolar-moment-revisited-391>; see also Hal Brands, Making the Unipolar Moment: U.S. Foreign Policy and the Rise of the Post–Cold War Order (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2016).

38 Julian Barnes, Anton Troianovski, and Robert Wall, “Europe Reckons with Its Depleted Armies,” Wall Street Journal, June 3, 2017, A1.

39 Brands, Dealing with Allies in Decline, i.

40 Ian Bremer, Superpower: Three Choices for America’s Role in the World (New York: Portfolio, 2015), 127–163.

41 Ian Bremmer and Cliff Kupchan, Top Risks 2017: The Geopolitical Recession, Eurasia Group, January 3, 2017, available at <www.eurasiagroup.net/issues/top-risks-2017>.

42 Mathew J. Burrows, David K. Bohl, and Jonathan D. Moyer, Our World Transformed: Geopolitical Shocks and Risks (Washington, DC: The Atlantic Council, April 2017).

43 Robert Kagan, “The Price of Power: The Benefits of U.S. Defense Spending Far Outweighs the Costs,” Weekly Standard, January 24, 2011.

44 Kier Giles, “Assessing Russia’s Reorganized and Rearmed Military,” Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, May 3, 2017, available at <http://carnegieendowment.org/2017/05/03/assessing-russia-s-reorganized-and-rearmed-military-pub-69853>.

45 Graham Allison, “America Second? Yes, and China’s Lead Is Only Growing,” Boston Globe, May 21, 2017, available at <www.bostonglobe.com/opinion/2017/05/21/america-second-yes-and-china-lead-only-growing/7G6szOUkTobxmuhgDtLD7M/story.html>.

46 See Michael J. Mazarr, “The Once and Future Order: What Comes After Hegemony?” Foreign Affairs, January/February 2017, 25–32.

47 Dakota Wood, 2016 Index of U.S. Military Strength: Assessing America’s Ability to Provide for the Common Defense (Washington, DC: Heritage Foundation, 2016).

48 Jim Garamone, “Dunford Details Implications of Today’s Threats on Tomorrow’s Strategy,” available at <www.jcs.mil/Media/News/News-Display/Article/926536/dunford-details-implications-of-todays-threats-on-tomorrows-strategy/>. In this article, General Dunford is quoted, “From a U.S. perspective, I would tell you I believe our center of gravity as a nation, through a security lens, is the network of alliances. Russia is trying to erode that.”

49 Andrew F. Krepinevich, Preserving the Balance: A U.S. Eurasia Defense Strategy (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 2017).

50 Michael J. Mazarr and Hal Brands, “Navigating Great Power Rivalry in the 21st Century,” War on the Rocks, April 5, 2017. See also Kyle Lascurettes, The Concert of Europe and Great-Power Governance Today: What Can the Order of 19th-Century Europe Teach Policymakers about International Order in the 21st Century? (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, February 2017).

51 On U.S. military force design see F.G. Hoffman, “Defense Policy and Strategy,” in Charting a Course: Strategic Considerations for a New Administration, ed. R.D. Hooker, Jr. (Washington, DC: NDU Press, 2016); Mark Gunzinger et al., Developing the Future Force: Priorities for the Next Force Planning Construct (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, August 2017).

52 Fruhling, 21.

53 Cornish and Donaldson, 277, 284.

54 I am indebted to Dan Flynn from the NIC for this point and for numerous insights on scenarios and their use in government.

55 I use the term script as a substitute for national or Service culture, more narrowly than Lawrence Freedman, Strategy: A History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 607–629.

56 Williamson Murray, MacGregor Knox, and Alvin Bernstein, eds., The Making of Strategy: Rulers, States and War (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 675.

57 Freedman, Strategy, ix.

58 Robert Meyer and Howard Kunreuther, The Ostrich Paradox: Why We Underprepare for Disasters (Philadelphia: Wharton Digital Press, 2017), 12.

59 General Mark Milley, USA, quoted in Sydney Freedberg, “Miserable, Disobedient, and Victorious: General Milley’s Future Soldier,” Breaking Defense, October 5, 2016, available at <http://breakingdefense.com/2016/10/miserable-disobedient-victorious-gen-milleys-future-us-soldier/>.