Download PDF

Brigadier General Bertram C. Providence, USA, is the Commanding General of Regional Health Command–Pacific. Lieutenant Colonel Derek Licina, USA, is the Chief of Global Health Engagements at Regional Health Command–Pacific. Colonel Andrew Leiendecker, USA, is the Assistant Chief of Staff for Operations at Regional Health Command–Pacific.

If you don’t know where you’re going, any road will take you there.

— Paraphrase from Lewis Carroll,

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

Why the Department of Defense (DOD) and international military sector writ large engage in global health is well documented.1 How DOD conducts global health engagement (GHE) in a systematic way is not. While pundits representing the Office of the Secretary of Defense, Joint Staff, combatant commands, Service components, and other organizations codify DOD policy for GHE, individuals and units implementing this broad guidance from 2013 to today continue to do so in a patchwork manner.2 Using the Indo-Asia Pacific region as a case study, this article presents the background regarding the current state of GHE in the region, develops a standardized GHE approach for engagement, and informs a partner-nation 5-year strategy.

Soldier assigned to USNS Mercy hands out basic hygiene kits to local Timorese children at Dona Ana Lemos Escuela elementary school in Gleno during Pacific Partnership 2016 health outreach event, June 15, 2016 (U.S. Navy/William Cousins)

Background

GHE operations, activities, and actions (OAA) are used to implement the Secretary of Defense Policy Guidance for DOD GHE and the U.S. Army Medicine 2017 Campaign Plan in direct support of the U.S. Pacific Command (USPACOM) theater campaign plan (TCP) and U.S. Army Pacific (USARPAC) theater campaign support plan.3 Analysis conducted by the Uniformed Services University Center for Global Health Engagement found that of 2,518 Army engagements entered into the Overseas Humanitarian Assistance Shared Information System from fiscal years 2002–2012, 21.4 percent (approximately 540) were executed by USARPAC at a cost of $96.4 million. Out of the 540 engagements across 24 countries in the region, 28 percent (approximately 153) were considered health related.

Despite significant investment, the lack of standardization in how GHE OAAs are executed results in fragmented programs that may not develop the health capability or increase the capacity of our partner nations (PNs) within the region. For example, the basic first responder (BFR) course has been conducted using various programs of instruction by different Services throughout the Indo-Asia Pacific region. The Air Force and Army National Guard also conducted BFR courses through the State Partnership Program using different programs of instruction. As a result, the lack of standardization in delivering the same course leaves partner nations in the region confused. Both military and civilian partners are left to assemble the training pieces that vary by doctrine and application, which may generate reputational risk for DOD. Additionally, variation of the same course among our own Services makes it difficult to build interoperability with our partner nations. There may be a need for some variation in course content to account for conditions that may differ between regions. However, a standard from which each of the Services, to include the State Partnership Program, can adapt and deliver predictable training to a partner nation is essential.

Lacking a common approach also makes it difficult for DOD and partner nations to track progress toward achieving learning objectives over time. As such, DOD and partner nations become co-dependent to teach BFR year after year. Furthermore, thinking through the next building blocks of partner-nation medical capacity is often overlooked. This myopic approach of conducting BFR annually using various programs of instruction consumes resources that could be spent on developing the next higher level of capability such as Advanced Trauma Life Support in support of a United Nations–level one or two deployable hospital.

To mitigate the problem, USPACOM established a standardized BFR program of instruction. The resulting curriculum and associated training packages are now used by validated trainers from all Services to include Active, Reserve, and Guard forces. This is an important step in recognizing the variability in funding through the Security Cooperation Program (SCP) where the Army may secure funding to conduct an initial BFR course this year only to be followed by the Air Force to validate partner-nation trainers the next. Leveraging a standardized program also increases overall DOD efficiency. The lean approach of reducing waste where each Service developed independent BFR programs also incorporates elements of Six Sigma, where variation in training products was eliminated. Using a standard approach allows individuals and units conducting the BFR course to objectively measure performance and effectiveness over time.

Despite this single example of success, no standardized program, process, or training packages exist for the other GHE OAAs conducted by DOD. These OAAs include the medical functional areas such as evacuation, logistics, and force health protection, among others, that make up a majority of the engagements. DOD policy now prescribes the requirement to “foster accurate and transparent reporting to key stakeholders on the outcomes and sustainability of security cooperation and track, understand, and improve returns on DOD security cooperation investments.” As SCP resources become more constrained, the ability to measure the impact of GHE using a standardized approach in support of partner-nation capacity-building is essential.

Developing a Standard Approach for GHE

In an effort to standardize health engagement execution and quantify measures of performance and effectiveness, the U.S. Army Regional Health Command–Pacific (RHC-P) built on the USPACOM Health Engagement Appendix of the TCP. The appendix uses three health lines of effort (HLOEs) to guide Service component GHE activities. The HLOEs are health system support, operational medicine, and public health/force health protection. Activities associated with the HLOEs include medical support to peacekeeping operations, basic first responder, humanitarian mine action, unique health needs of the female Servicemember, maternal/child health, and emerging infectious diseases, among others. The idea of binning health activities into HLOEs is constructive, and RHC-P refined these based on existing medical functional area doctrine.

A review of Army medical doctrine led to the development of 3 Army HLOEs based on 10 doctrinal medical functional areas (FA):4

- health system support

- health service support

- force health protection.

The 10 FAs are:

- combat and operational stress control

- combined information data

- casualty care

- dental services

- laboratory services

- medical evacuation

- medical intelligence

- medical logistics

- mission command

- preventive medicine and veterinary services.

Army Medicine is organized, trained, and equipped along these FAs. Employing an engagement strategy using doctrinal FAs increases efficiencies in capitalizing on existing military capabilities and standardizes the manner in which health engagements are conducted, assessed, monitored, and evaluated. Each of these HLOEs and their associated FAs are outlined below.

First, the Army health system support HLOE includes programs intended to build capability and increase capacity of PN military health systems to provide support across the range of military operations and types of mission support. Military operations include theater opening, early entry, expeditionary, detainee, humanitarian assistance/disaster relief, and peacekeeping operations. Mission support includes traditional assistance to a deployed force, operations predominantly characterized by stability tasks, and defense support of civil authorities. This HLOE includes the following FAs: mission command, medical intelligence, and combined information data. In addition, two USPACOM J07 (Command Surgeon) health engagement activities fall into this category: medical support to peacekeeping operations and medical support to humanitarian assistance/disaster relief.

Second, the health service support HLOE includes programs intended to increase capacity and capability of military and civilian health systems, as well as direct support to those systems. This HLOE assists the partner nations in maintaining a level of health care conducive to supporting the health of the population, bolstering confidence in governance, and lowering the susceptibility to destabilizing influences. Any engagement with PN civilian health systems is coordinated with the ministries of health and U.S. Government agencies involved in health programs. These agencies include the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Global Affairs, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The health service support HLOE includes military-military and military-civilian engagement across the following FAs: casualty care (medical treatment, hospitalization, dental services, behavioral health, clinical laboratory services), medical evacuation, and medical logistics. In addition, seven USPACOM J07 health engagement activities are binned into this category: basic first responder, trauma combat casualty care, mental health, medical logistics, humanitarian mine action, unique health needs of the female Servicemember, and maternal/child health.

Third, the force health protection HLOE supports the health of U.S. military personnel, PN militaries, and general public by mitigating disease risks. This HLOE includes the following FAs: preventive medicine, veterinary services, combat and operational stress control, dental services, and laboratory services (area medical laboratory support). In addition, the USPACOM J07 health engagement activities of emerging infectious diseases and tropical medicine fall into this category for planning purposes.

Building 5-Year Health Engagement Strategies

Using doctrinal medical FAs to inform how the Army in the Pacific executes health engagements, RHC-P designed FA playbooks to socialize the concept with personnel instrumental in the SCP. The FA playbooks include the following six elements: doctrinal definition of the capability; list of units potentially available to support health engagements in the FA; international military education and training courses available for PN attendance through Department of State appropriations; a doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership, personnel, and facilities scorecard to assess capability and track progress over time; an idealized engagement strategy to build the FA capability and increase capacity over a 5-year period; and an example concepts of operation to stimulate thought and discussion in designing an appropriate health engagement strategy. The FA playbooks were constructed to socialize with Service component and combatant command security cooperation country/regional desk officers; Embassy personnel such as the Office of Defense Cooperation, USAID, HHS (CDC Liaisons); and PN representatives from various ministries such as defense and health, among others.

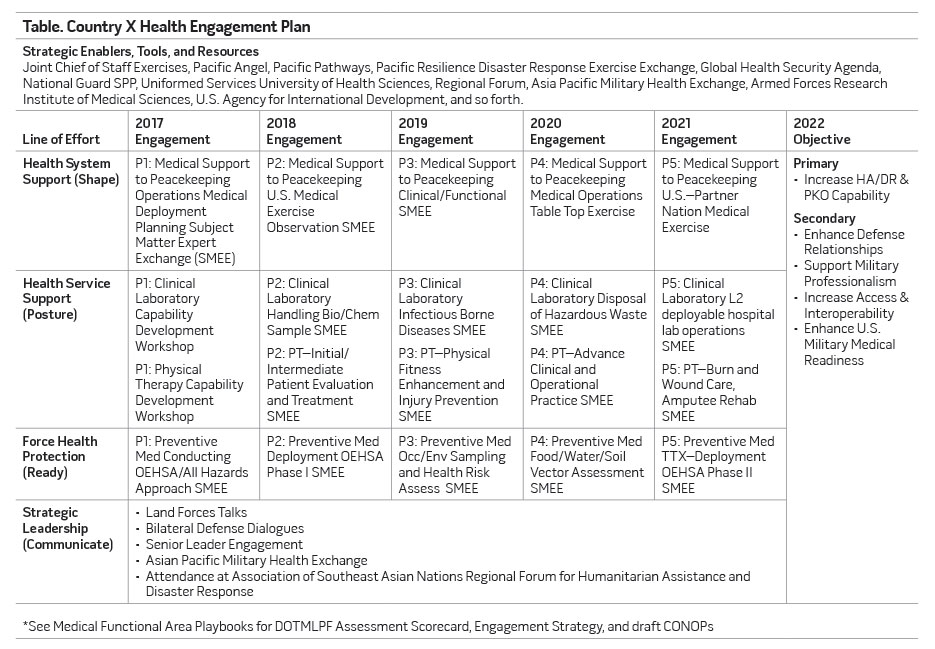

During the annual combatant command security cooperation planning cycle, these FA playbooks would inform discussions with the aforementioned organizations and lead to the design of health engagement project proposals. This approach informs a 5-year health engagement strategy within the countries of interest that supports combatant command country security cooperation plans and Ambassadors’ integrated country strategy. The strategy is then translated into a single slide depicting engagements along the three HLOEs, by FA, to achieve a strategic Service component and/or combatant command objective (see table). These strategies are used to inform senior leader discussions such as bilateral defense dialogues conducted by the combatant command and Service components. Focusing senior leader talking points and discussions on these strategies leads to bilaterally agreed to actions that sustain GHE programming to support TCP objectives.

The FA playbooks and associated 5-year strategies were socialized with great success during the 2016 USPACOM Security Cooperation Capability Development Working Group (CDWG) held in Honolulu. The CDWG is the single most important event in the Indo-Asia Pacific security cooperation planning process where engagement OAAs are reviewed and coordinated in advance of project nomination submissions. The playbooks and 5-year strategy tools were received with enthusiasm by myriad SCP officers. In numerous CDWG country synchronization sessions, these officers requested a single point of accountability by branch (for example, health) to synchronize the often redundant project nominations. The health community is positioned to support this request for two reasons:

- The USPACOM Theater Campaign Order assigns a single Service component coordination responsibility for health engagements in designated countries.

- The FA playbooks and associated 5-year strategies allow for all Services (to include Guard and Reserve) to focus their nominations on building capacity in support of a common TCP objective.

The USARPAC Assistant Chief of Staff for Medicine is using the responsibility assigned through the Theater Campaign Order, FA playbooks, and 5-year strategies with great success in synchronizing health engagement proposals among all Services, Guard, and Reserve. Furthermore, the playbooks and strategy tools were presented during the 2016 Association of Military Surgeons United States Annual Meeting and as part of the DOD Global Health Engagement Capabilities Based Assessment conducted from 2016–2017. Key leaders representing multiple Services, combatant commands, and Service components expressed interest in scaling up the use of these standardized tools immediately.

Although the playbooks and strategies are based on Army doctrine, all Services can incorporate their comparative advantage into the three HLOEs to ensure DOD does not duplicate efforts and gains efficiency and effectiveness in executing GHE. Each combatant command can select the most appropriate FA and engagement strategy to meet its TCP objectives. Partners in the U.S. Central Command area of responsibility may seek casualty care support while those in the U.S. Southern Command and U.S. Pacific Command areas of responsibility seek laboratory and preventive medicine support. The laboratory and preventive medicine FA playbooks and strategies could help DOD and U.S. interagency partners in supporting partner nations through the Global Health Security agenda. The opportunities are great.

Hospital Corpsman performs cataract surgery on Fijian patient aboard hospital ship USNS Mercy, June 13, 2015, during Pacific Partnership 2015 (U.S. Air Force/Peter Reft)

However, the FA playbooks are not perfect. The U.S. Army Medical Command recently tasked the U.S. Army Medical Department Center and School to develop training packages in line with each FA playbook. The Uniformed Services University Center for Global Health Engagement also expressed interest in potentially developing joint training packages based on the FA playbooks to further standardize how all DOD executes health engagement. Both initiatives will fill a gap and support quality improvement of health engagement executed by individuals and units, assessment of their impact, and lead to an increase in PN capability and capacity.

Through global health engagements based on standardized HLOEs and doctrinal FAs, the Department of Defense reassures allies and key regional partners of American commitment, prepares regional partners to assume multinational leadership roles, opens lines of communication with new partners, and sustains access to countries with limited capacity to contribute toward regional and international security. Furthermore, health engagements implement the Secretary of Defense Policy Guidance for DOD GHE, Army Medicine 2017 Campaign Plan, USARPAC Theater Campaign Support Plan, and USPACOM TCP.5

Using this standardized approach to DOD GHE in a time of fiscal constraints is not only a wise investment of the limited resources available, but also increases the credibility of the DOD military healthcare system to leadership, elected officials, taxpayers, and the partners with whom we serve. JFQ

Notes

1 Josh Michaud, Kellie Moss, and Jen Kates, The U.S. Department of Defense and Global Health (Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation, September 2012), available at <https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/8358.pdf>; Derek Licina, “The Military Sector’s Role in Global Health: Historical Context and Future Direction,” Global Health Governance 6, no. 1 (Fall 2012), 1–30, available at <http://blogs.shu.edu/ghg/files/2012/12/VOLUME-VI-ISSUE-1-FALL-2012-The-Military-Sector’s-Role-in-Global-Health-Historical-Context-and-Future-Direction.pdf>.

2 Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, “Department of Defense Instruction TBD Global Health Engagement, 2016” (draft); Department of Defense (DOD) Instruction 5132.14, “Assessment, Monitoring, and Evaluation Policy for the Security Cooperation Enterprise,” January 31, 2017, available at <http://open.defense.gov/portals/23/Documents/foreignasst/DoDI_513214_on _AM&E.pdf>; Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations/Low Intensity Conflict (ASD-SO/LIC), “Policy Guidance for Department of Defense Global Health Engagement,” 2013.

3 ASD-SO/LIC; Army Medicine 2017 Campaign Plan (Washington, DC: Headquarters Department of the Army, 2017), available at <http://armymedicine.mil/Documents/Army_Medicine_2017_ Campaign_Plan.pdf>; U.S. Pacific Command (USPACOM), “Theater Campaign Plan 5000-20, Base Plan,” 2013; U.S. Army Pacific Command (USARPAC), “Theater Campaign Support Plan,” 2016 (draft).

4 Field Manual 4-02, Army Health System (Washington, DC: Headquarters Department of the Army, 2013).

5 ASD-SO/LIC; Army Medicine 2017 Campaign Plan; USPACOM; USARPAC.