DOWNLOAD PDF

The United States faces an unprecedented threat from terrorism today: two

transregional networks actively plot attacks, recruit foreign fighters, and seek

to inspire “lone wolf” terrorists. But this threat is manageable. Rather than

trying to defeat terrorist adversaries, U.S. strategy should emphasize reducing

the risk of significant attacks in the homeland, Western Europe, Canada, and

Australia. In addition to homeland security measures, such a strategy would

be characterized by a shift, and likely an increase, in the placement of U.S.

special operations forces and intelligence assets overseas. Managing this threat

would also require greater coordination with, and persistence from, other

instruments of national power, including diplomacy and law enforcement. The

key counterterrorism challenge for a new administration, therefore, is how to

develop and sustain a strategy that manages this threat persistently, without

being on a constant war footing.

This chapter addresses the counterterrorism challenges facing U.S.

policymakers today. To do so, it focuses on foreign terrorist groups

and how they threaten the United States and its allies in Western Europe,

Canada, and Australia. Of course, most of these terrorist groups

also pose a threat to regional stability, as addressed in other chapters.

But this chapter prioritizes the safety of the U.S. homeland, citizens, and

residents. It argues that not only the primary threat to the United States

comes from two transregional terrorist networks but also that the Nation

faces an unprecedented threat from foreign fighters and individuals inspired

by those transregional networks. This combination can be difficult

to disrupt persistently, whether overseas or inside the United States.1

So the key counterterrorism challenge for policymakers today is how the

U.S. Government can manage this threat without being on a constant

war footing.

Threats Posed by Terrorist Networks

This section provides an overview of the foreign terrorist and insurgent

groups that pose a threat to the United States, as well as the nature and

extent of that threat. Note that significant research exists on how and

why terrorism arises, why individuals become involved in terrorism,

how terrorist groups generate and maintain support, and why terrorism

declines.2 This section does not delve into that research. Instead it posits

that groups with transregional objectives and reach present the greatest

threat to the U.S. homeland and its allies in Western Europe, Canada,

and Australia. Subsequent sections address the threats posed by foreign

fighters and lone wolves in greater depth.

The Islamic State and Its Provinces

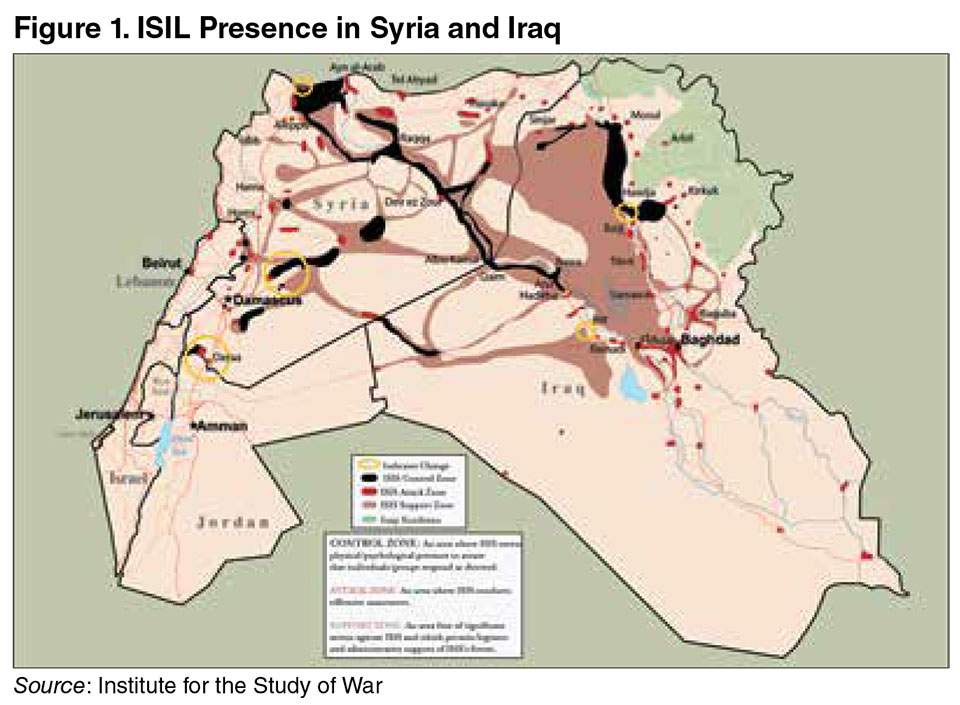

The primary threat to the U.S. homeland today emanates from the Islamic

State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL).3 Led by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi,

ISIL maintains its headquarters in Raqqah, Syria, and Mosul, Iraq.

Beyond these two cities, ISIL either controls movement (or at the very

least retains freedom of movement) across territory in both countries (see

figure 1).4 So it is often referred to as a terrorist group, an insurgency, and

a proto-state. ISIL has an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 local fighters, as

well as foreign fighters, also known as “volunteers,” who have traveled to

Iraq and Syria to assist with the struggle against Syrian President Bashar

al-Asad and join ISIL’s newly established caliphate.5 Experts assess that ISIL had an annual revenue of between $265 million and $615 million as

of late 2015, stemming from local taxation, oil, kidnapping for ransom,

smuggling, and other forms of crime, although their revenue decreased

in 2016.6 ISIL leaders utilize this revenue, and personal relationships

built over the years, to reinforce their authority over “provinces” that

have been established outside the borders of Syria and Iraq, including

Afghanistan, Algeria, Bangladesh, Egypt, Indonesia, Libya, Nigeria, Pakistan,

Russia (Chechnya), Saudi Arabia, Somalia, and Yemen.7

In June 2014, ISIL spokesman Abu Muhammad al-Adnani announced

the creation of an Islamic caliphate in the territory under ISIL’s control in

Iraq and Syria, changing his organization’s name from the Islamic State

of Iraq and the Levant to simply “Islamic State.”8 The primary message

from al-Adnani at the time was that the Islamic State had established

governing structures and religious law in its territories, and thus all Muslims

had a religious obligation to transfer their allegiance to ISIL and

relocate to this newly established caliphate.9 Al-Adnani’s announcement

was accompanied by additional military victories, territorial gains, and a

concerted social media campaign to terrorize local and international opponents

in 2014 and 2015.10 Militant groups in the outlying provinces of

ISIL’s so-called caliphate also have followed its lead, adopting ISIL tactics

and using social media to advertise their campaigns.

While most of this violence has been directed inward or toward the

local residents of territories under dispute, ISIL and its affiliates also have

attacked international targets. Examples of international terrorist attacks

by ISIL and loyal groups include:

- August 2014: ISIL fighters decapitated American journalist James

Foley. The beheading was videotaped and posted online.11

- June 2015: A gunman attacked a beach vacation resort in Tunisia,

killing 38 individuals.12

- November 2015: Paris came under attack by ISIL fighters; 129 people

died.13

- March 2016: Twin suicide attacks on the airport and subway system

in Brussels killed 32 individuals; responsibility for the attacks was

claimed by ISIL.

Notably, prior to the Paris and San Bernardino attacks, terrorism experts

debated whether ISIL or al Qaeda presented the greatest threat to

the United States, especially the U.S. homeland.14 This debate centered on two key assumptions. First, some experts assumed that ISIL leaders

were focused exclusively on the battle for control over territory in Syria

and Iraq and, therefore, would not attempt to reach beyond those countries.

As a corollary, because ISIL leaders prioritized the near enemy (for

example, so-called apostate Muslim regimes) over the far enemy (for example,

the United States), it would not sponsor external attacks.15

Second, other experts assumed that ISIL would experience a backlash

among Muslim communities for its brutality on the battlefields of Syria

and Iraq. Examples of ISIL brutality included the widely disseminated

beheadings of Western journalists.16 ISIL also captured and then burned

alive a Jordanian pilot in February 2015. This assumption drew on past

experience with ISIL’s predecessor, al Qaeda in Iraq (AQI), which faced

significant backlash after its members conducted its own decapitation

campaign against Iraqi officials and foreign journalists throughout 2004

and then subsequently attacked a wedding party in Jordan in November

2005.17

Yet events eventually called both of these assumptions into question.

In the early summer of 2014, for example, rumors circulated that ISIL

had begun to reach out to militant groups that were associated with al

Qaeda but were disgruntled with its leadership and direction. These

rumors were substantiated several months later as terrorist groups in

Afghanistan, Algeria, Chechnya, Egypt, Libya, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Somalia,

and Yemen declared their allegiance to, and were formally accepted

by, ISIL.18

Additionally, an unprecedented number of foreign fighters—30,000 in

Iraq and Syria and 5,000 in Libya by November 2015—continued to travel

overseas to join ISIL.19 This constant flow of foreign fighters, even after

the highly publicized beheadings, suggested that the anticipated backlash

was unlikely to occur. It was coupled with an escalating number of plots

both directed and inspired by ISIL leadership.20 Indeed, investigations

into the Paris and Brussels attacks subsequently revealed that al-Adnani

had been given responsibility over external operations as early as January

2014.21 It therefore became increasingly obvious that ISIL posed the greater

threat to North America, Western Europe, and Australia.

Al Qaeda and Its Affiliates

If ISIL represents the primary terrorist threat to the United States in

2016, al Qaeda and its associates should not be ignored entirely. Currently

led by Ayman al-Zawahiri, al Qaeda was responsible for the attacks

on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon in September 2001.22 It has

been a prominent actor in the wider Salafi jihadi movement since the

mid-1980s, initially under the auspices of Maktab al-Khidamat.23 Much of al Qaeda’s worldview and ideology parallels ISIL. But al Qaeda leaders

prioritize attacks against the far enemy over the near enemy.24 Al Qaeda

leaders also have cautioned their adherents to avoid Muslim casualties

whenever possible.25 These divergences are not insignificant. They have

caused a rift not only between jihadists on the battlefields of Syria and

Iraq but also worldwide. Al-Zawahiri apparently anticipated this rift; in

May 2013 he designated an emissary to the conflicts in Syria and Iraq,

Abu Khalid al-Suri, in an attempt to resolve these differences. But al-Suri

was killed by ISIL fighters in February 2014.26

Al Qaeda, in contrast to a more hierarchical ISIL, has retained its networked

structure over the years. Often described as a franchise, al Qaeda

senior leaders reportedly remain based in Pakistan, but they provide

guidance to affiliated militant groups around the world. These affiliates

include al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), al Qaeda in the Islamic

Maghreb (AQIM), al Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent, and the

al-Nusra Front in Syria.27 Additionally, the Khorasan Group, also based

in Syria, is comprised of experienced al Qaeda fighters from Afghanistan

and Pakistan who traveled to Syria to fight the Asad regime.28 In

total, al Qaeda and its affiliates have an estimated 8,700 fighters globally,

although it is worth noting that the majority of these fighters exist

with affiliated groups, not core al Qaeda.29 Al Qaeda leaders also have

established ties to the Taliban, Haqqani network, Tehrik-e-Taliban, and

Lashkar-e-Tayyba in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

The rise of ISIL, its 2014 declaration of a caliphate, and subsequent

defections clearly put pressure on al Qaeda leaders to demonstrate their

relevance to the wider Salafi jihadi movement, of which both ISIL and al

Qaeda are part. They have responded to this pressure by positioning al

Qaeda as the most viable alternative to ISIL for those Muslims who do

not feel comfortable with ISIL’s tactics on the battlefield. Al Qaeda leaders

also have rebuked ISIL for causing disunity within the Salafi jihadi

movement. The following joint statement by AQAP and AQIM illustrates

this approach: “On top of this the [ISIL] spokesman declared war on all

groups and factions everywhere and threatening to fight and shed their

blood. This indicated the extent of their deviation and misguidance. Instead

of directing their fight towards the enemies of the ummah, and to

direct their arrows towards the Jews and Christians, they chose to direct

their arrows towards the chests of Muslims.”30

Al Qaeda affiliates also have tried to revive their own efforts against

the United States and its allies. This has manifested itself in the emergence

of new al Qaeda training camps in Afghanistan and attacks by

al Qaeda affiliates against Western targets overseas.31 These include an

attack by AQAP on the office of the Charlie Hebdo satirical magazine in Paris in January 2015 and an attack by AQIM on the Radisson Blu hotel

in Mali in December 2015. That said, neither of these attacks reached

the level of death, injury, or damage as those conducted by ISIL fighters.

Will al Qaeda fully reemerge in 2017? Will al Qaeda join with ISIL

to form a united transregional network? Will this united network pose

an even greater threat? These are the questions being asked by terrorism

analysts today. The answers will likely depend on the extent to which

the United States and its partners can maintain pressure on ISIL and al

Qaeda’s transregional networks simultaneously. Over the past decade, al

Qaeda senior and mid-level leaders have been targeted by U.S. and other

counterterrorism forces (see figure 2). It is arguable that these and other

intensive efforts have diminished al Qaeda’s ability to attack North America,

Western Europe, or Australia or even to mount significant attacks

on Western targets overseas. But this type of counterterrorism campaign

requires concerted resources, including intelligence collection and analysis,

law enforcement and diplomatic pressure, and, in many cases, the

use of U.S. military instruments, primarily U.S. special operations forces

(SOF) and airpower. These resources are finite, and tradeoffs exist. It

still remains an open question as to whether the U.S. Government can

effectively combat two transregional terrorist networks, as well as maintain

its readiness against more conventional state adversaries. The new

administration, Democratic or Republican, will have to reconcile these

national security priorities.

|

Figure 2. Select Al Qaeda Leaders Killed by Counterterrorism Forces

|

|

Naseer al-Wuhayishi (2015), AQAP leader and deputy to Ayman al-Zawahiri

|

|

Sanafi al-Nasr and Muhsin al-Fadhli (2015), leaders of the Khorasan Group

|

|

Abu Yahya al-Libi (2012), al Qaeda spokesman and commander in Afghanistan

|

|

Saaed al-Sherhri (2012), AQAP founder and former Guantanamo prisoner

|

|

Anwar al-Awlaki (2011), American-born cleric and recruiter for AQAP

|

|

Atiyah ‘Abd al-Rahman (2011), deputy leader for al Qaeda in Pakistan

|

|

Osama Bin Laden (2011), the founder and visionary behind al Qaeda

|

Lebanese Hizballah and Lashkar-e-Tayyba

In addition to ISIL, al Qaeda, and their affiliates, two additional transregional

terrorist networks are worthy of note for U.S. national security

policymakers. Neither of these networks poses a threat to the United

States today, but they should be monitored for shifts in intent and behavior.

The first, Lebanese Hizballah, has not threatened the United States

directly since the early 1980s. But despite this absence, it often emerges

in discussions of transregional terrorist networks that might pose a threat

in the future. This is due in part to its relationships with Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), Shia militias in Iraq, the Palestinian

Islamic Jihad, and Huthi rebels in Yemen.32

Led by Hassan Nasrallah, Hizballah has maintained strong ties to Iran

since the 1980s.33 Originally an actor in the Lebanese civil war, Hizballah

shifted its attention to Israel and its forces in southern Lebanon after a

power-sharing arrangement was reached for the governance of Lebanon

as part of the 1989 Ta’if Agreement.34 Today, Hizballah reportedly has

5,000 fighters under its command in Lebanon with up to 2,000 more

deployed to assist President Asad’s forces in Syria.35 Its close ties with

the IRGC also provide Hizballah with access to weapons and financing,

and, in some instances, the two have been accused of collaborating on

terrorist attacks.36 Hizballah’s transregional network also has reach into

the United States, albeit in a limited way. In March 2014, for example,

Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agents arrested a Lebanese-born

American for attempting to travel to Syria to fight with Hizballah; he

reportedly received between $500 and $1,000 for his trip.37

Lashkar-e-Tayyba (LeT) also deserves some mention as another

transregional terrorist network that might pose a threat (albeit much

less so than the other networks discussed in this chapter) to the United

States and its allies in the future. Based in Pakistan, LeT is led by Hafiz

Muhammed Saeed and has a fighting force of between 750 to several

thousand.38 LeT has ties to al Qaeda and the Haqqani network, but it

also operates its own independent network, stretching from Pakistan

to Saudi Arabia to the United States.39 In November 2008, gunmen associated

with LeT attacked the Taj Hotel in Mumbai as well as 11 other

sites, killing 164 people. U.S. citizen David Headley pleaded guilty in

March 2010 to scouting targets for this attack.

New Dynamics

The United States also faces two additional counterterrorism challenges:

increased numbers of foreign fighters and lone wolves. This section addresses

these two threats as they exist now and how they might evolve

in the future.

Foreign Fighters

As of November 2015, 30,000 foreign volunteers had traveled to Syria

and Iraq either to fight against the Assad regime or otherwise support

the ongoing battles; an additional 5,000 were believed to be in Libya.40

While foreign fighters are not a new phenomenon, these numbers are

unprecedented (see table 1). For example, an estimated 20,000 foreign

volunteers fought against Soviet forces in Afghanistan between 1980 and 1992; that is an average of 1,650 foreign fighters entering the conflict

per year.41 Similar numbers existed for Operation Iraqi Freedom. Approximately

5,000 foreign fighters traveled to Iraq between 2004 and 2009 to

fight against U.S. forces for an average of 1,000 per year.42 These averages

are hardly comparable to the current conflicts: 7,500 volunteers per year

for Syria and Iraq and 2,500 per year for Libya.

|

Table. Basic Comparison of Foreign Fighters

|

|

Country (Years of Conflict)

|

Volunteers

|

Average Volunteers per Year

|

|

Syria (2012–2015)

|

30,000

|

7,500

|

|

Iraq (2004–2009)

|

5,000

|

1,000

|

|

Afghanistan (1980–1992)

|

20,000

|

1,650

|

Some debate exists, however, as to the nature and extent of the threat

posed by foreign fighters to the U.S. homeland, Western Europe, Canada,

or Australia. Most agree that foreign fighters can provide unique skills to

terrorist groups, such as medical skills or how best to use social media.

But questions remain about how many will return home and whether

those who do will conduct attacks there. The latter represents a key concern

for Western Europe today. If 30,000 foreign volunteers are in Syria

and Iraq, for example, some can be expected to be killed on battlefields.

Estimates vary. A report by the Soufan Group suggests that approximately

7 percent have been killed on battlefields.43 A separate report released

by the Brookings Institution cites an estimate by European intelligence

officials of 20 percent.44 By comparison, a report by Al-Manar, the television

news source associated with Hizballah, estimates 37 percent.45 It

is difficult to take numbers from Hizballah—ISIL’s archenemy—too seriously.

Nonetheless, if we use the high-range number of 37 percent killed

on battlefields, this still leaves 18,800 foreign fighters remaining in Iraq

and Syria with an additional 3,150 remaining in Libya. Roughly 15 percent

of these are estimated to be from North America, Western Europe,

or Australia, equating to 3,293 Western foreign fighters.46

From a counterterrorism perspective, over 3,000 Western fighters still

represents a fairly significant number, given the ease with which they

can travel throughout Western countries and the historical difficulties

that intelligence and law enforcement have experienced in monitoring

them. Clearly not all will return home to conduct attacks or will commit

terrorist acts if they do return. But some will. Estimates vary on potential

recidivism rates from 9 percent to as high as 60 percent (see figure 3).47

This variance suggests that more needs to be done to understand how

foreign fighters travel to conflicts, when and how they return home, and

how they will behave upon their return. Abdel Hamid Abaaoud, one of

the leaders of the November 2015 attacks in Paris, for example, recruited at least two dozen additional team members to conduct this attack. Seven

of the nine attackers were foreign fighter returnees from Syria. Two were

Iraqis. But most of the other team members—13 in total—had not traveled

to Syria or Iraq to fight, suggesting that returnees represent more of a

threat than their initial numbers might suggest because they could recruit

others to their cause.48

|

Figure 3. Western Foreign Fighters after Battlefield Losses

|

|

15 percent of 18,900 in Syria and 3,150 in Libya = 3,293 total

|

|

Recidivism

Estimate: 9 percent

296 return home to conduct attacks

|

|

Estimate: 15 percent

494 return home to conduct attacks

|

|

Estimate: 60 percent

1,976 return home to conduct attacks

|

Notably, the FBI thus far has managed the risk to the U.S. homeland

posed by foreign fighter returnees successfully, while security services

in France and Belgium have not done as well. The question for a new

administration is whether the FBI can sustain this level of effort within

the United States in the mid-term or increase its investigations as more

foreign fighter returnees reenter the United States.

Lone Wolves

Experts use the term lone wolves to denote residents of the United States

who plan or participate in terrorist attacks without direct support or

operational guidance from terrorist leaders. Some lone wolves are inspired

by conflicts overseas. Others are part of local paramilitary groups,

white supremacists, or even environmental activists. Members of the

U.S.-based Sovereign Citizen Movement, for example, have targeted

local police officers in Arkansas, Connecticut, Florida, Nebraska, New

Hampshire, and Wisconsin.49 This section focuses only on lone wolves

inspired by transregional terrorist networks, namely ISIL and al Qaeda.

According to Director James Comey, the FBI had open investigations

on suspects associated with or inspired by ISIL in all 50 states as of February

2015.50 Recent examples of lone wolf attacks include an attack by

two men against an event in Garland, Texas, in May 2015 and the death

of 14 people in San Bernardino, California, in December 2015. While

some experts dispute the danger to the U.S. homeland posed by foreign

fighters, most agree that lone wolves represent a real threat.

Significant research has been devoted to understanding why the current

conflicts have inspired so many lone wolves and attracted so many

foreign fighters. Most studies, one way or another, point to the relatively sophisticated social media campaign waged by ISIL.51 In characterizing

this sophistication, experts generally make two key observations. First,

while the production of ISIL messages tends to be centralized, the dissemination

is diffuse. This means that it is difficult to “shut down” ISIL

messaging.52 Second, ISIL messages appear to be targeted toward specific

audiences, including foreign recruits, as illustrated by its English-language

magazine, Dabiq.53 Comey has taken this assessment one step further,

arguing that ISIL uses social media platforms to target messages

directly to recruits via smartphones.54 While less appears to be known

about which messages resonate with specific audiences, it seems clear

that ISIL’s use of social media has contributed to the increase in plots by

lone wolves within the United States.

Policy Implications

In summary, the primary terrorist threat to the U.S. homeland, Western

Europe, Canada, and Australia today emanates from ISIL; al Qaeda represents

a secondary threat; and Hizballah and Lashkar-e-Tayyba represent

potential future threats. Given the nature and extent of these threats,

the U.S. Government faces three main counterterrorism challenges: how

to counter two transregional networks simultaneously, how to anticipate

and halt the emergence of new transregional networks, and how to mitigate

the danger posed by lone wolves and foreign fighters. These tasks

are not easy. But while it is impossible to provide a thorough counterterrorism

policy in this chapter, the following steps represent a viable way

forward for a new administration.

First, a new administration should take the opportunity to revisit the

access and placement overseas necessary for the U.S. Government to

sustain activities against the ISIL and al Qaeda transregional networks,

as well as anticipate emerging threats. “Access and placement,” in this instance,

refers to the allocation of not only U.S. SOF but also intelligence

assets, FBI legal attachés, and other law enforcement personnel, such as

Customs and Border Protection and Drug Enforcement Administration

officers.55 The Barack Obama administration has already taken several

steps in this direction by increasing the number of SOF deployed to Syria

and Iraq and delaying their withdrawal from Afghanistan.56 But given

the counterterrorism challenges outlined in this chapter, a new administration

is unlikely to be able to rely solely on SOF and airpower. It will

also need to leverage even more nonmilitary assets, such as diplomacy,

intelligence, and law enforcement.

Second, a new administration should take the opportunity to revisit

the authorities and structure within the executive branch needed to counter ISIL, al Qaeda, or other transregional networks effectively. For

example, as a new administration develops a way forward to counter

these threats, it may want to request an additional Authorization for the

Use of Military Force from Congress. It may also need to revisit intelligence-

sharing relationships and partnerships. Equally important, as a

new administration devotes more nonmilitary assets toward countering

these threats, this will require close coordination across the government.

The National Counterterrorism Center could help bring all of the Federal

agencies together, but it cannot direct the reallocation of resources

toward this fight. Such an effort will need to be undertaken by the White

House.57

Third, the United Nations has undertaken multiple efforts to mobilize

the international community against foreign fighter flows. These efforts

include Security Council Resolution 2178, passed in September 2014,

that requires member countries to prevent their citizens from traveling

abroad to join terrorist organizations.58 The United Nations also has attempted

to work with member states to tighten their legal frameworks

against foreign fighter flows, as well as identify any needs for technical

assistance, especially with respect to advance passenger information.59 A

new administration should take the opportunity to broaden this effort so

that it focuses on not only outbound travel but also returnees. Specifically,

the ceasefire and transition negotiations should address the dilemma

of what to do with foreign fighters residing within Syria and Iraq. Some

countries, such as Russia, have decided to revoke the citizenship of their

foreign fighters. But it is not in the interest of the United States to allow

these fighters to remain in Syria or relocate to another conflict. The issue

of returnees should receive more diplomatic emphasis, forethought, and

planning. Similarly, the United Nations should be encouraged to emphasize

the challenges posed by recidivism, to identify lessons learned, and

to help member states put programs in place now before they experience

an unmanageable surge of returnees. A new administration should

prioritize assistance to these efforts, whether it be diplomatic, information-

sharing, or providing technical support and resources to member

states.

Fourth and finally, a new administration should conduct a full and

thorough review of the U.S. Government’s efforts to counter messaging

by ISIL, al Qaeda, and potentially other transregional terrorist networks.

This will not be easy. Multiple departments and agencies play a role in

what is referred to as public diplomacy, strategic communications, information

operations, or counter-messaging. But opportunities exist. For

example, defectors from ISIL have begun to speak out. Refugees also

have told their stories of horrible treatment and losses, which undermine ISIL’s claim to a legitimate caliphate. And just as social media assists ISIL

and al Qaeda, it also can be used to gauge the nature and the extent

to which ISIL and al Qaeda messages resonate with local populations

around the world. But the U.S. Government must have appropriate authorities,

structures, resourcing, and plans to take advantage of these

opportunities.

The United States faces an unprecedented threat from terrorism today,

emanating from a combination of transregional terrorist networks,

foreign fighters, and the lone wolves that they inspire. Yet this threat

does not necessitate that the United States be on a constant war footing.

It can be managed. Doing so, however, requires the U.S. Government to

prioritize its military and intelligence assets appropriately, coordinate its

diplomatic efforts more effectively, and expand the use of law enforcement

instruments for combating terrorism not only inside the United

States but also overseas.

Notes

1 See, for example, Jesse Byrnes, “FBI Investigating ISIS Suspects in All 50 States,” The Hill, Briefing Room Blog, February 25, 2015, available at <http://thehill.com/blogs/blogbriefing-room/233832-fbi-investigating-isis-suspects-in-all-50-states>; Molly O’Toole, “Is Whack-A-Mole Working Against al Qaeda?” Defense One, June 16, 2015, available at <www.defenseone.com/threats/2015/06/whack-mole-working-against-al-qaeda/115450/>.

2 For a summary of this extensive research, see Paul K. Davis and Kim Cragin, eds., Social Science for Counterterrorism: Putting the Pieces Together (Santa Monica, CA: RAND,

2009); see also Kim Cragin, “Resisting Violent Extremism: A Conceptual Model for Non-Radicalization,” Terrorism and Political Violence 26, no. 2 (2014), 337–353.

3 For additional information on this group, see Michael Weiss and Hassan Hassan, ISIS: Inside the Army of Terror (New York: Regan Arts, 2015). Note that some experts still

believe that al Qaeda poses the greatest threat.

4 Note that the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) lost control over territory in 2016. For further discussion on gauging ISIL control over territory, see Kathy Gilsinan,

“The Many Ways to Map the Islamic State,” The Atlantic, August 27, 2014, available at <www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2014/08/the-many-ways-to-map-the-islamicstate/379196/>.

5 Subsequent sections address the foreign fighter flows into Syria and Iraq in greater detail. For additional references, see Patricia Zengerle, “U.S. Fails to Stop Flow of Foreign

Fighters to Islamic State,” Reuters, September 29, 2015, available at <www.reuters.com/article/2015/09/29/us-mideast-crisis-congress-fighters-idU.S.KCN0RT1VZ20150929>;

Michael Pizzi, “Foreign Fighters in Syria, Iraq Have Doubled Since Anti-ISIL Intervention,” Al-Jazeera, December 7, 2015, available at <http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2015/12/7/foreign-fighters-in-syria-iraq-have-doubled-since-anti-isil-intervention.html>.

6 These numbers do not account for approximately $500 million to $800 million taken from Iraqi state-owned banks. See Guy Taylor, “Islamic State Among ‘Best Funded’

Terrorist Groups on Earth: Treasury Department,” Washington Times, October 23, 2014, available at <www.washingtontimes.com/news/2014/oct/23/isis-best-funded-terroristgroup-earth-treasury/?page=all>; Frank Gunter, “ISIL Revenues: Grow or Die,” Foreign Policy Research Institute, June 19, 2015, available at <www.fpri.org/articles/2015/06/isilrevenues-grow-or-die>.

7 “Islamic State Expands into Pakistan with Tehrik-e-Khalifat,” Jane’s Terrorism and Insurgency, January 30, 2015; Lara Jakes, “Who’s Part of the Islamic State? Depends

on Who You Ask,” Foreign Policy, May 21, 2015, available at <http://foreignpolicy.com/2015/05/21/whos-part-of-the-islamic-state-depends-whom-you-ask/>; Charlie Winter, “The Virtual ‘Caliphate’: Understanding Islamic State’s Propaganda Strategy,” Quilliam Foundation, July 2015, available at <www.quilliamfoundation.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/publications/free/the-virtual-caliphate-understanding-islamic-states-propaganda-strategy.pdf>; Aaron Zelin, “New Video Message from the Islamic State: ‘Victory from God and an Imminent Conquest—Wilayat al-Khayr,’” Jihadology.net, May 11, 2015, available at <http://jihadology.net/2015/05/11/new-video-message-from-the-islamic-statevictory-from-god-and-an-imminent-conquest-wilayat-al-khayr/>.

8 Abdallah Suleiman Ali, “ISIS Announces Islamic Caliphate, Changes Name,” Pascale al-Khoury, trans., al-Monitor.com, June 30, 2014, available at <www.al-monitor.com/pulse/security/2014/06/iraq-syria-isis-announcement-islamic-caliphate-name-change.html#>.

9 Abu Muhammad al-Adnani, “This Is the Promise of Allah,” statement released by al-Hayat Media Center, June 30, 2015.

10 For more information on territorial gains over time by ISIL, see the excellent maps developed by the Institute for the Study of War, available at <www.understandingwar.org/>; for more information on ISIL’s media campaign, see Aaron Zelin, “Picture or It Didn’t Happen: A Snapshot of the Islamic State’s Official Media Output,” Perspectives on

Terrorism 9, no. 4 (August 2015), available at <www.washingtoninstitute.org/uploads/Documents/opeds/Zelin20150807-Perspectives.pdf>; Ali Fisher, “Swarmcast: How Jihadist

Networks Maintain a Persistent Online Presence,” Perspectives on Terrorism 9, no. 3 (June 2015), available at <http://terrorismanalysts.com/pt/index.php/pot/article/view/426/

html>; Winter.

11 For an account of this and other kidnappings, see James Harkin, Hunting Season: James Foley, ISIS and the Kidnapping Campaign that Started a War (New York: Hachette,

2015).

12 Ben Hubbard, “Terrorist Attacks in France, Tunisia, and Kuwait Kill Dozens,” New York Times, June 26, 2015, available at <www.nytimes.com/2015/06/27/world/middleeast/

terror-attacks-france-tunisia-kuwait.html?_r=0>.

13 Andrew Higgins and Kimiko de Freytas-Tamura, “Paris Attack Suspect Killed in Shoot Out Had Plotted Terror for 11 Months,” New York Times, November 19, 2015, available at <www.nytimes.com/2015/11/20/world/europe/paris-attacks.html?ref=liveblog&_r=0>.

14 President Barack Obama, in this context, compared ISIL fighters in Fallujah, Iraq, to junior varsity basketball players. See Steve Contorno, “What Obama Said About the

Islamic State as a ‘JV’ Team,” PolitiFact, September 7, 2014, available at <www.politifact.com/truth-o-meter/statements/2014/sep/07/barack-obama/what-obama-said-about-islamic-state-jv-team/>.

15 For further discussion on the near enemy versus far enemy debate in the wider Salafi jihadi movement, see Gilles Kepel, Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam (London: I.B. Tauris, 2002); Fawaz A. Gerges, The Far Enemy: Why Jihad Went Global (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

16 For an account of these kidnappings, see Harkin.

17 Ibid., 176; Hassan M. Fattah and Michael Slackman, “Three Hotels Bombed in Jordan; At Least 57 Die,” New York Times, November 10, 2015, available at <www.nytimes.com/2005/11/10/world/middleeast/3-hotels-bombed-in-jordan-at-least-57-die.html>.

18 Liam Stack, “How ISIS Expanded Its Threat,” New York Times, November 14, 2015, available at <www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/11/14/world/middleeast/isis-expansion.html>.

19 Subsequent paragraphs discuss the issue of foreign fighters in depth. It is worth noting that as of mid-2016, the number of foreign fighters was estimated to be approximately

27,500, with some departing for home or other conflict zones and others being killed on battlefields.

20 Byrnes.

21 Rukmini Callimachi, “How ISIS Built the Machinery of Terror Under Europe’s Gaze,” New York Times, March 29, 2016, available at <www.nytimes.com/2016/03/29/world/europe/isis-attacks-paris-brussels.html>.

22 “Al-Qaeda Names Ayman al-Zawahiri as Osama bin Laden’s Successor,” statement issued on jihadist forums, June 16, 2011, translated and reposted by SITE Intelligence

Group.

23 Kepel; Gerges.

24 Ibid.

25 Ayman al-Zawahiri, “Letter to Zarqawi on Campaign in Iraq,” July 9, 2005, translated and released by West Point Counterterrorism Center, available at <www.ctc.usma.edu/v2/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Zawahiris-Letter-to-Zarqawi-Translation.pdf>; Abu Musab al-Suri, “Call for Global Islamic Resistance,” unpublished paper released December 2004/January 2005, translated and posted by SITE Intelligence Group, February 16, 2007; Abu Laith al-Libi, “Confronting the War of Prisons,” as-Sahab Media, May 24, 2007, translated and posted by SITE Intelligence Group.

26 “Militants Kill al Qaeda Emissary in Syria,” Jane’s Terrorism and Insurgency Monitor, February 25, 2014.

27 Some fighters from al Qaeda affiliates have defected to ISIL. See Greg Miller, “Fighters Abandoning al Qaeda to Join the Islamic State, U.S. Officials Say,” Washington

Post, August 9, 2014, available at <www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/fighters-abandoning-al-qaeda-affiliates-to-join-islamic-state-us-officials-say/2014/08/09/c5321d10-1f08-11e4-ae54-0cfe1f974f8a_story.html>.

28 When some experts argue that al Qaeda remains the most significant threat to the U.S. homeland, they tend to reference the Khorasan Group. See Bruce Bennett, “Airstrikes

in Syria Also Target Little Known Khorasan Group,” Los Angeles Times, September 23, 2014, available at <www.latimes.com/world/middleeast/la-fg-khorasan-20140923-story.

html>.

29 Estimates for the numbers of al Qaeda fighters come from a variety of sources, including Bennett; see also “Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan is Attempting a Comeback,” Fox

News, October 21, 2012, available at <www.foxnews.com/world/2012/10/21/al-qaeda-in-afghanistan-is-attempting-comeback.html>; “Mapping Militant Organizations,”

Stanford University, available at <web.stanford.edu/group/mappingmilitants/cgi-bin/groups/view/493>.

30 “AQAP and AQIM Give Scathing Rebuke of IS in Joint Statement,” November 1, 2015, translated and reposted by SITE Intelligence Group, November 1, 2015.

31 Eric Schmitt and David E. Sanger, “As U.S. Focuses on ISIS and the Taliban, Al-Qaeda Reemerges,” New York Times, December 29, 2015, available at <www.nytimes.com/2015/12/30/us/politics/as-us-focuses-on-isis-and-the-taliban-al-qaeda-re-emerges.html?ref=topics&_r=0>.

32 Sirjah Wahab, “Hizballah Operating in Yemen with Houthis,” Arab News, March 28, 2015, available at <www.arabnews.com/featured/news/724391>; “Palestinian Islamic Jihad,” profile posted by the Government of Australia, available at <>; Mushreq Abbas, “Iran Looks to Iraq for Syria Support,” trans. Joelle el-Khoury, al-Monitor.com, September 13, 2013, available at <www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2013/09/iran-looks-for-support-from-iraq.html>.

33 For more information on Lebanese Hizballah, see Hala Jaber, Hezbollah: Born with a Vengeance (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997); Naim Qassam, Hizballah: The

Story from Within (London: Saqi Books, 2005); Augustus Richard Norton, Hizballah: A Short History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009).

34 Hassan Krayem, “The Lebanese Civil War and the Taif Agreement,” Digital Documentation Center, American University of Beirut, n.d., available at <http://ddc.aub.edu.lb/projects/pspa/conflict-resolution.html>.

35 As with ISIL and al Qaeda, the numbers for Lebanese Hizballah and its fighting force tend to vary widely. A general consensus appears to be 10,000 from sources. But Tony Badran, at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, questions these numbers in his blog. He cites a Lebanese intelligence official as estimating a force of 5,000. Similarly, some discrepancies exist on the number of Hizballah forces deployed to Syria, ranging from several hundred to 2,000. For more information, see Tony Badran, “Hezbollah and the Army of 12,000,” April 7, 2013, available at <https://now.mmedia.me/lb/en/commentaryanalysis/hezbollah-and-the-army-of-12000>; Dexter Filkins, “The Shadow

Commander,” The New Yorker, September 30, 2013, available at <www.newyorker.com/reporting/2013/09/30/130930fa_fact_filkins>; Abbas.

36 Kim Cragin, “Hizballah, Party of God,” in Aptitude for Destruction, ed. Brian Jackson et al. (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2005).

37 Abha Shankar, “Dearborn Man Arrested Trying to Join Hizballah Fighters in Syria,”Investigative Project Blog, March 18, 2014, available at <www.investigativeproject.org/4318/dearborn-man-arrested-trying-to-join-hizballah#>.

38 The National Counterterrorism Center Web site states that Lashkar-e-Tayyba has several thousand fighters, while the South Asia Terrorism Portal Web site estimates 750.

See “Lashkar e Tayyba,” available at <www.nctc.gov/site/groups/let.html> and <www.satp.org/satporgtp/countries/india/states/jandk /terrorist_outfits/lashkar_e_toiba.htm>.

39 Ibid.

40 Zengerle; Pizzi.

41 The number 20,000 represents a high-end estimate. See Thomas Hegghammer,“The Rise of Muslim Foreign Fighters,” International Security 35, no. 3 (Winter 2010/2011), 61.

42 Ibid.

43 Richard Barrett, Foreign Fighters in Syria (New York: Soufan Group, June 2014), available at <http://soufangroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/TSG-Foreign-Fightersin-

Syria.pdf>.

44 Daniel Byman and Jeremy Shapiro, Be Afraid, Be a Little Afraid: Western Foreign Fighters in Syria and Iraq, Policy Paper 34 (Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution,

November 2014), 20.

45 “9936 al Qaeda-linked Arabs Killed in Syria,” al-Manar.com, December 24, 2013, available at <www.almanar.com.lb/english/adetails.php?fromval=1&cid=23&-frid=23&eid=126949>.

46 The 15 percent comes from estimated totals: 30,000 foreign fighters and 4,500 from the West.

47 Byman and Shapiro.

48 These numbers were calculated based on the ratio for the Paris attacks—3 foreign fighters: 10 local recruits.

49 The Lawless Ones: The Resurgence of the Sovereign Citizen Movement, Special Report by the Anti-Defamation League, 2nd ed. (New York: Anti-Defamation League, 2012), available at <www.adl.org/assets/pdf/combating-hate/Lawless-Ones-2012-Edition-WEBfinal.pdf>.

50 Byrnes.

51 See, for example, Byman and Shapiro; Winter; Zelin, “Picture or It Didn’t Happen”; Barrett; see also Scott Shane and Ben Hubbard, “ISIS Displaying a Deft Command

of Varied Media,” New York Times, August 30, 2014, available at <www.nytimes.com/2014/08/31/world/middleeast/isis-displaying-a-deft-command-of-varied-media.html?_r=0>.

52 Jyette Klausen, “Tweeting the Jihad: Social Media Networks of Western Foreign Fighters in Syria and Iraq,” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 38, no. 1 (December 2014), 1–22; Fisher; J.M. Berger and Jonathan Morgan, The ISIS Twitter Census: Defining and Describing the Population of ISIS Supporters on Twitter, Analysis Paper 20 (Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, March 2015).

53 Ibid. See also Zelin, “Picture or It Didn’t Happen.”

54 Kevin Johnson, “FBI Director Says Islamic State Influence Growing in U.S.,” USA Today, May 7, 2015, available at <www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2015/05/07/isisattacks-us/70945534/>.

55 Under the leadership of Admiral William McRaven, U.S. Special Operations Command explored the possibility of establishing what was referred to generally as a “global SOF network.” This proposition came under significant criticism and so did not gain traction among policymakers. This chapter does not advocate a return to the global SOF network, but rather, a more limited presence in the form of a series of Special Operations Command–Forward elements attached to Embassies or consulates. For more information, see Posture Statement of Admiral William H. McRaven, Commander, United States Special Operations Command, before the 113th Congress House Armed Services Committee, March 6, 2013, available at <http://docs.house.gov/meetings/AS/AS00/20130306/100394/HHRG-113-AS00-Wstate-McRavenU.S.NA-20130306.pdf>; Jack Jensen, “Special Operations

Command–Forward Lebanon: SOF Campaigning Left of the Line,” sidebar in reprint of Michael Foote, “Operationalizing Strategic Policy in Lebanon,” Special Warfare (April–June 2012).

56 Jim Acosta and Jeremy Diamond, “Obama Again Delays Afghanistan Troop Drawdown,” CNN, October 15, 2015, available at <www.cnn.com/2015/10/15/politics/afghanistan-troops-obama/index.html>.

57 For further discussion on how to improve interagency performance against these types of threats, see Christopher J. Lamb’s chapter on national security reform in this volume.

58 Somini Sengupta, “Security Council Passes Resolution to Thwart Foreign Fighters,” New York Times, September 24, 2014, available at <www.nytimes.com/news/un-general-assembly/2014/09/24/security-council-passes-resolution-to-thwart-foreign-fighters/?_r=0>.

59 United Nations, “Action Against Threat of Foreign Terrorist Fighters Must Be Ramped Up, Security Council Urges in High-Level Meeting,” Press Release No. 11912,

May 29, 2015, available at <www.un.org/press/en/2015/sc11912.doc.htm>.