The national security system has grown substantially since World War

II, but its ability to handle complex and dynamic problems has not

changed much.1 Therein lies the problem: As the security environment

grows increasingly complex and dynamic, the current system remains

unable to coordinate multiple elements of power and thus cannot contend

with multidimensional threats or keep pace as they rapidly evolve.

Consequently, the system performs increasingly poorly, and as a result,

it is now commonplace for national security leaders to support national

security reform. As Congressman Ike Skelton (D-MO) observed in 2010,

“For many years, we’ve repeatedly heard from independent blue-ribbon

panels and bipartisan commissions that . . . our system is inefficient,

ineffective, and often down-right broken.”2 Congressman Skelton was

not exaggerating. One national-level blue-ribbon review after another

has concluded the national security system needs reform,3 and virtually

all published assessments of the system by individual leaders and experts

reach the same conclusion.4

The reasons national security reform has not yet taken place are surveyed

elsewhere.5 However, one key impediment to reform is the influential

but false assumption that fixing the system would be too difficult

and costly. In reality, Congress and the President could easily solve the

primary problem bedeviling the system in three straightforward steps:

- pass legislation allowing the President to empower “mission managers”

to lead intrinsically interagency missions

- make a concerted effort to create the collaborative attitudes and

behaviors among Cabinet officials necessary for mission managers

to succeed

- adopt a new model of a National Security Advisor with responsibility

for system-wide performance.

These reforms would be politically and bureaucratically challenging but

not expensive.

Mission Manager Authority

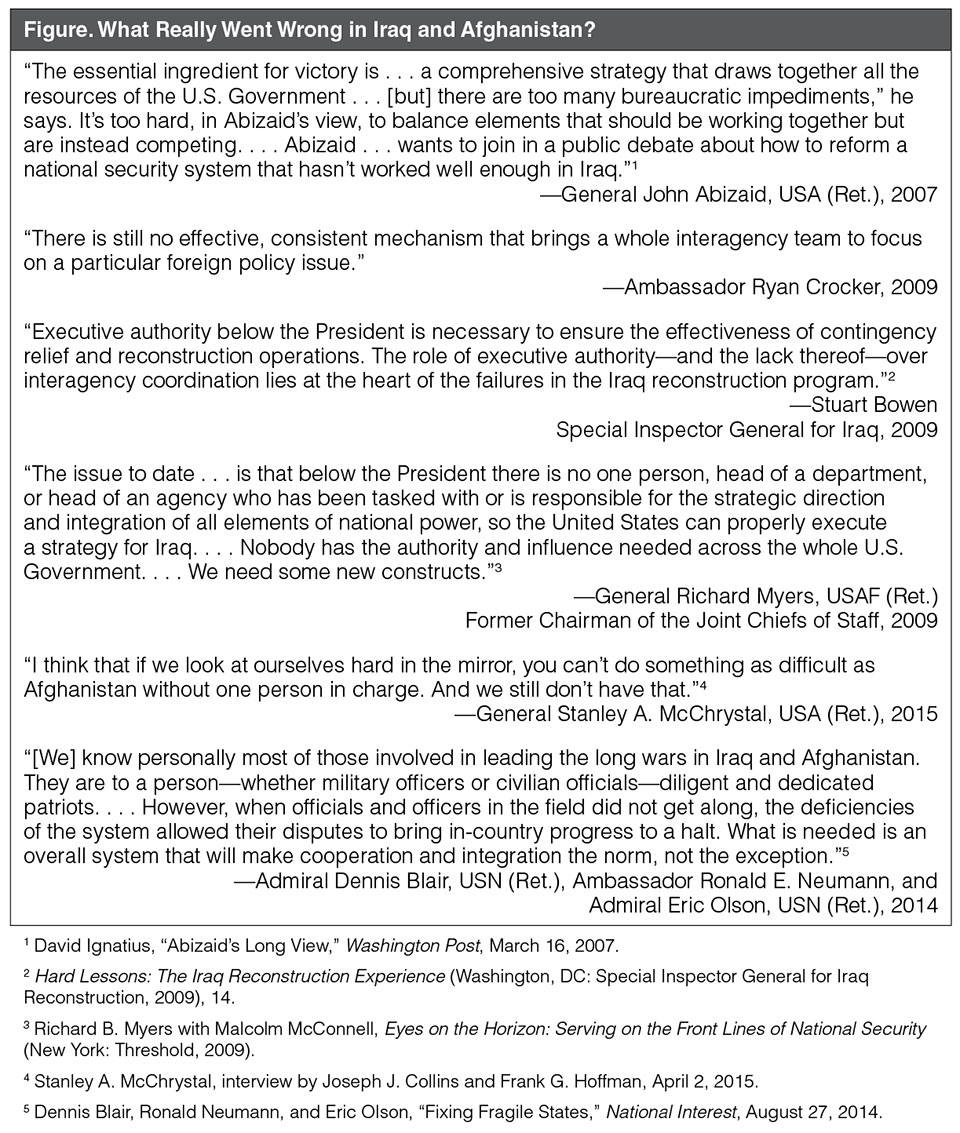

There is widespread agreement on the number-one problem plaguing

the national security system: executive branch departments and agencies

too often compete instead of collaborate, making it difficult if not impossible

to achieve national security objectives. Few collective enterprises

can succeed without unity of effort, and it is widely recognized that our

national security system does a poor job in this regard. Many senior military

and diplomatic leaders insist that our lack of success in Afghanistan

and Iraq is best explained by just such an absence of unified effort (see

figure). As these leaders argue, such complex, dynamic security problems

are not managed well because no one other than the President has

the authority to direct and integrate the efforts of departments and agencies,

and he is too busy to do so. Orchestrating national security missions

requires sustained attention, and Presidents simply do not have the time

to manage even the most important security problems on a continuous

basis. The President is the de jure commander in chief but a de facto

“commander in brief.”6 As Ambassador Richard Holbrooke argued long

ago, Presidents can usually decide on policy for high-priority matters,

and “if it involves few enough agencies and few enough people . . . even

carry it out,” but “the number of issues that can be handled in this personalized

way is very small.”7

The President’s all-encompassing span of control and limited time

also explain why the current mechanisms to help the President generate

unified effort are ineffective. The hierarchy of interagency committees

that are supposed to coordinate policy and strategy and oversee their

consistent implementation can only suggest, not direct, activities. In our

system, “interagency committees, conveners, and lead agencies are basically

organized ways of promoting voluntary cooperation”8 and are thus often ineffective if not a waste of time.9 The interagency groups either

come to a stalemate over differences or, as former Secretary of State Dean

Acheson argued, reach “agreement by exhaustion” while “plastering

over” differences.10 Lead agency and other approaches to coordination

also have proved ineffective.11

Seeing the need for better unified effort, Congress has passed laws

that assign a designated individual responsibility for coordinating an issue

area. Yet Congress never really empowers these individuals. Statutes

designating coordinators for countering narcotics, countering weapons

of mass destruction, and managing foreign relations all include limits

and loopholes that invite departments and agencies to ignore or bypass

the integrating official.12 Many worry that fully empowering Presidential subordinates to produce unified effort across the executive branch would

confuse lines of authority from the President down through his Cabinet

officials to their field activities. Yet all organizations with functional

structures like the U.S. national security system have to balance the need

for a clear line of authority down through functional capabilities with

the need to integrate those capabilities to accomplish cross-cutting objectives.

Where this balancing act takes place depends on the extent to

which the organization is centralized. The range of problems that the

organization must manage and how quickly it evolves should determine

the optimal degree of centralization. Less centralization and more

cross-cutting integration is needed to operate effectively in a complex

and dynamic environment. But in the current system, deference to those

in charge of functional capabilities routinely trumps the prerogatives of

anyone charged with coordinating multifunctional missions, forcing issues

upward for more centralized control by the President. The President

needs to reverse this flow and delegate the executive authority for integrating

the efforts of departments and agencies to a subordinate of his

or her choice: a person sometimes referred to as a “mission manager.”13

It may seem surprising that the President, empowered by the Constitution

to act as Chief Executive, cannot currently delegate his authority

for integrating the work of departments and agencies. However, the

stipulated authorities of the Cabinet officials have increased and been

consolidated in law over the past 60 years. The 1947 National Security

Act and its subsequent amendments, including the Goldwater-Nichols

Department of Defense Reorganization Act of 1986, greatly strengthened

the authority of the Secretary of Defense. The 1977 Department of Energy

Organization Act created the Department of Energy and rolled up

several agencies’ responsibilities into that new organization, empowering

the Secretary of Energy. The Homeland Security Act of 2002 combined

22 separate organizations into the Department of Homeland Security,

empowering another new Cabinet official. The Intelligence Reform and

Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 established the Office of the Director

of National Intelligence and empowered the director to oversee and

manage the Intelligence Community.

The numerous codified authorities of Cabinet officials often provide a

legal basis for ignoring “czars” charged by the President with overseeing

a cross-cutting mission area. An example is the chain of command for

military operations. Goldwater-Nichols specified that it runs “from the

President to the Secretary of Defense and from the Secretary of Defense

to the commander of a Combatant Command.”14 The Department of Defense

(DOD) used this provision to claim control of postwar planning

for Iraq and ignore other departments. DOD argued that military forces would be involved and that the chain of command to those forces went

through the Secretary of Defense, and thus DOD should be in charge of

the entire interagency effort.15

Actually, Goldwater-Nichols gives the President other options because

it includes the caveat “unless otherwise directed by the President.”16

However, for the President to insert anyone else in the military chain of

command, or delegate decision authority over other departments and

agency activities, other legal requirements must be met:

The President may, pursuant to 3 U.S.C. § 301, delegate

particular functions to “the head of any department or

agency in the executive branch, or any official thereof” who

is subject to Senate confirmation. To qualify as a delegable

function, a function must be “vested in the President by

law” or vested in another officer who performs the function

“subject to the approval, ratification, or other action

of the President.” [Furthermore,] “Any individual in the

interagency space who exercises meaningful authority to

compel departments to act” would have to be an “officer of

the United States,” and officers of the United States must

have their positions established by statute as required by

the Appointments Clause of the Constitution.17

Czars informally tapped by the President to coordinate an issue area

do not meet these requirements. Thus we need new legislation for this

purpose. It should empower the President to appoint and empower mission

managers to lead cross-functional teams irrespective of pre-existing

statutes. Only then could the President effectively delegate his authority

for directing the efforts of the executive branch in a particular mission

area involving capabilities “owned” by multiple Cabinet officials. Something

like the following language suggests what is needed:

The President may designate individuals, subject to Senate

confirmation, to lead interagency teams to manage clearly

defined missions with responsibility for and presumptive

authority to direct and coordinate the activities and operations

of all of U.S. Government organizations in so far

as their support is required to ensure the successful implementation

of a Presidentially approved strategy for accomplishing

the mission. The designated individual’s presumptive

authority will not extend beyond the requirements for

successful strategy implementation, and department and agency heads may appeal any of the designated individual’s

decisions to the President if they believe there is a compelling

case that executing the decision would contravene

public law or do grave harm to other missions of national

importance.18

Another reason for codifying the authorities in statute is the need to

secure resources for the President’s mission manager:

“The President may create structures and processes and

fund them temporarily by transferring resources, but ultimately

it is Congress that provides resources on a sustained

basis. Without Congress’s input and resources, a presidentially

imposed solution to interagency integration may

wither for lack of funding.” Thus, the statute . . . would

likely also require a mechanism for funding their activities

and associated congressional oversight.19

Resource requirements vary greatly by mission. Countering disinformation

may require nothing more than a compelling forensic case to

discredit disinformation, whereas arming and training foreign forces require

funds to purchase weapons and training. Whatever the resources

required, ultimately Congress provides them to the executive branch,

and a mission manager would need to keep Congress apprised of his or

her activities. Given the authorities invested in each mission manager,

Congress would want these officials to be subject to Senate confirmation.

Collaborative Cabinet

Legislation allowing the President to empower selected subordinates to

direct executive branch activities is the key prerequisite for successful

national security reform.20 However, it is not sufficient. Structural adjustments

in authorities must be accompanied by less visible but equally

important elements of organizational performance.21 When senior leaders

in the private sector impose hasty reforms without sufficient support

and follow-up, the usual result is failure. A President imposing mission

managers on his Cabinet officials and National Security Council (NSC)

staff without supporting measures would also fail.22 To succeed, the President

will have to personally lead a concerted effort to shape leadership

attitudes and behavior, staff skills, and the organizational culture of the

NSC staff.

The place to begin is Cabinet officials and their expectations. The

President would have to explain the need to use mission managers rather

than the traditional interagency committees for high-priority, intrinsically

interagency missions. Leaders of functional departments who want

to protect their turf and fear losing control of their own operations and

agendas are the greatest threat to the success of such cross-functional

teams.23 A case in point is U.S. Northern Command (USNORTHCOM).

One commander of USNORTHCOM established cross-directorate Focus

Area Synchronization Teams to improve overall organizational effectiveness

and collaboration on key mission areas in 2010, and they produced

good results. The teams also irritated the leaders of USNORTHCOM’s

functional staff directorates, who convinced a new incoming commander

to dismantle them.24 The same thing apparently happened to similar

efforts to reform Marine Corps headquarters.25 Functional leaders argue

cross-cutting teams lack sufficient expertise, confuse lines of authority,

and are inefficient. If they sense the senior leader (in this case the President)

is not fully committed, they typically exert control over their representatives

on teams by reminding them pointedly to “remember who you

work for.” Under this kind of pressure, team members stalemate over the

way forward or compromise to the point of incomprehension. The group

becomes a committee whose members protect their parent organizations’

equities rather than a team focused on accomplishing the mission. In

such cases the poor results seem to justify the observation that the team

is just another layer of useless bureaucracy.

When teams are allowed to perform, their results demonstrate their

worth and, over time, resistance fades. However, resistance from functional

departments often cripples the teams before they can demonstrate

their potential.26 Despite everyone’s interest in serving the Nation and

safeguarding its security, similar issues will arise when a President decides

to use mission managers leading interagency teams. To ensure

mission managers have a chance to succeed, the President would have

to personally communicate support for them and allay the concerns of

Cabinet officials. The President should make the following points to his

Cabinet:

- Mission managers are necessary. An abundance of historical cases

illustrates the inadequacy of our existing mechanisms. As experience

also teaches, our mechanism for managing complex problems

must mirror the complexity of the security problem it tackles.27 It

must be a truly multifunctional, interagency team empowered to

formulate, consider, and pursue fully integrated approaches. As

President, I need to hear more than competing military, diplomatic, and intelligence perspectives. I need alternative but fully integrated

interagency approaches. Past examples of such teams clearly

demonstrate they perform with much greater proficiency than czars

or lead agencies.28

- Mission managers will not dilute your authority. If we have learned

anything since 9/11, and arguably since World War II, it is that no

one Cabinet official can direct another Cabinet official to do anything.29 Thus, none of you, no matter how talented, dedicated, or

insightful on a particular issue, can lead and control an integrated,

interagency approach to solving inherently interagency problems.

Because you do not currently have this authority, you are not losing

it to mission managers when we empower them to lead a well-defined

mission. If the problem is largely a diplomatic, military, or intelligence

problem, it will be managed by the Secretary of State, Secretary

of Defense, or Director of National Intelligence, respectively.

When we assign an interagency problem to a mission manager, it is

because none of you are in a position to manage the problem well

yourselves.

- Mission managers will manage the problem “end to end.” The mission

manager will assess the evolution of his or her mission; develop

policy; propose and execute a strategy for dealing with the issue;

conduct or oversee all requisite planning for associated operations;

oversee implementation of policy, strategy, and plans; and evaluate

progress, solving problems as they arise and adjusting as necessary.

When mission managers discover an impediment to progress, I expect

them to intervene selectively but decisively to ensure mission

success. They will drill down to whatever level of detail is necessary

to identify the origin of suboptimal performance and remove it, and

I will encourage their doing so within the bounds of the procedures

outlined below.

- Mission managers may impact your equities. If this occurs, you have

two remedies: one advantage of mission managers is that they are

singularly focused on and held accountable for outcomes. The disadvantage

is that their mission focus inclines them to ignore other

legitimate concerns. They may take actions that complicate other

national security objectives or that complicate your ability to manage

your departments and agencies to best effect. We will prevent

that from happening in two ways.

- The first way is through strategy concurrence. After being assigned

a mission, the mission manager will conduct a review of the situation

and, after due deliberation with his or her team, propose

strategy alternatives with associated resource implications. We will

meet and agree upon the best strategy. Any concerns of yours will be

noted and addressed at that time. My staff will codify our decisions

in a directive that clarifies the mission manager’s mission, strategy,

authorities, and resources. The mission manager’s authority will

only extend to the parameters of the assigned mission, consistent

with the strategy we discuss and I approve. If the strategy requires

amendment, we will meet to consider its revision. However, once

we agree upon these elements, I expect you to support the mission

manager.

- The second way is through implementation objections. When we select

mission managers and issue them mission directives, we will choose

highly competent senior leaders who understand the importance of

treating your institutions with respect. However, if they transgress

the bounds of their mission directive or inadvertently make decisions

with dire consequences for the welfare of your department or

agency, I expect you to raise the issue. We will then quickly meet to

adjudicate the competing objectives, risks, and anticipated benefits.

I expect you to raise principled rather than bureaucratic concerns. I

will not protect perceived prerogatives or respond to exaggerated allegations

of harm to your organizations or the national interest that

are clearly less important than the mission we are trying to execute.

This right of appeal has worked well elsewhere.30

- Mission managers must succeed. The missions assigned to mission

managers are critical for the security of the Nation. They cannot

be allowed to fail for lack of support. The presumption is that the

mission manager is empowered by me to manage the problem and

direct executive branch activities as they best see fit. The NSC staff

will ensure the mission manager and team have the resources they

need to succeed, including office space, communications, administrative

support, and team members committed for specific periods

of duration. The mission manager will decide what expertise the

team needs, and I expect you to make that kind of expertise available.

I expect those members to be rewarded if the team succeeds,

and above all, I expect your subordinates to avoid the temptation

to control members of the mission team. If the mission manager

concludes a team member is simply representing his or her parent organization’s interests rather than trying their best to accomplish

the mission, that person will be dismissed. If members of your organization

are repeatedly dismissed for lack of collaboration, I will

conclude that you personally do not support these priority national

security efforts.

The President could go on to underscore some major advantages to

doing business this way. In contrast to a Deputies Committee, which

meets periodically and must examine a host of security problems, mission

managers and their teams would be able to pursue their issue full

time, enabling them to better keep abreast of developments. Because

they are empowered they could manage problems end to end. Rather

than simply promulgating broad and often obscure policy and hoping

for the best as departments and agencies implement it, mission manager–

led teams would be able to quickly zero in on any impediment to

their success wherever it occurs. Because teams are not hamstrung by the

need for political consensus, and their authority is commensurate with

their responsibilities, they could make clear choices and take decisive

action.

Another advantage is that this approach would make the best use

of the President’s time. Currently, Presidents are often asked to review

briefings from departments and agencies intended to keep them informed

and comfortable with general policy and progress on a range of

issues, but seldom are these meetings structured to ensure that the really

contentious issues are highlighted for Presidential attention. In fact,

such issues are often downplayed to avoid confrontation. Using mission

managers, a President could be confident that the full, integrated capabilities

of the U.S. Government are being used to solve high-priority

problems consistent with an approved strategy and that any major problems

hampering the effort would be brought to the President’s attention.

Department heads would not embarrass themselves by raising marginal

concerns, so only the most consequential issues would arise for Presidential

decision, which are precisely the kind of hard decisions only the

President has the power to make. An example from recent history was

the Pentagon’s concern that surging forces in Iraq in 2007 ran the risk of

breaking the Army and elevating the risk of war in other theaters where

enemies might seek to take advantage of overextended U.S. ground forces.

These were legitimate concerns that the President needed to hear and

rule on, which he did.31

Best of all, mission managers would be accountable. A President cannot

currently hold anyone accountable for failure to manage complex security

threats because no one other than the President has the authority to orchestrate the multiple lines of effort they require. In this respect the

President faces precisely the same dilemma that the chairman and chief

executive officer of Xerox was dealing with when the chairman observed:

We see attractive markets, and we have superior technology.

On the other hand, we won’t be able to take advantage

of this situation unless we can overcome cumbersome,

functionally driven bureaucracy. . . . we were functional in

nature. So every function . . . all came up the line and, in

the end, reported to me. . . . I was the only one responsible

for anything in its entirety. If a product . . . did not [meet]

success, there was no clear way to see what went wrong.

Finger-pointing and shifting the blame were inevitable. The

only one responsible for the failure of that product, therefore,

was me.32

Xerox solved its accountability problem by empowering cross-functional

teams, and the President will have to do the same if he wants anyone empowered

and thus accountable for dealing with similar cross-functional

problems in the national security environment.

Many senior leaders like the idea of a cross-cutting team but believe

it should simply advise the President rather than exercising executive

authority. This would sidetrack the team’s success and must be avoided

at all costs. One reason such teams succeed is their ability to focus fulltime

on managing the cross-cutting mission. They make numerous small

decisions that move the effort forward and communicate constantly. If

they are merely advisory and can take no action without appealing to

the President, much of this energy is vitiated and the President will inevitably

be called upon to rule on innumerable lesser disputes, which

negates the value of the mission manager from the President’s point of

view. Also, if the teams are not empowered they will not behave as if they

are responsible for outcomes. Instead they will concentrate on providing

“good advice.” Instead of being singularly focused on accomplishing

their mission, they will worry about what sounds reasonable; what

Cabinet officials and the majority of informed observers will support; or

what they know of the President’s inclinations. Finally, department heads

would take the “advisory” designation as clear evidence the President

is not serious about empowering the group. Accordingly, they would

protect their institution’s narrow equities and support efforts by others

to do the same.

New Model of Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs

The third change necessary is a new model of National Security Advisor.33 The current model emphasizes the National Security Advisor as an

honest broker, ensuring the decisionmaking process fairly represents the

positions of the different departments and agencies on any given issue,

resolving conflicts and elevating the most important disagreements to

the President for resolution. The honest broker role is often contrasted

with powerful National Security Advisors such as Henry Kissinger and

Zbigniew Brzezinski, who unabashedly advocated policies and tried to

engineer their implementation.

In reality, all National Security Advisors must balance their roles as

process managers and confidential advisors to the President. As process

managers, they must be trusted by Cabinet officials to articulate their department’s

views fairly. For this reason, high-level interagency committees

have competing department and agency positions to contend with,

not integrated strategy choices for the President’s consideration. If advisors

and their staffs took input from the departments and agencies and

redefined it into a set of integrated alternatives, they would be accused of

trying to direct outcomes. Similarly, if National Security Advisors or NSC

staff are too creative in summarizing the results of discussion at meetings

(as they are on occasion), they again risk alienating the Cabinet officials.

In such circumstances, the departments and agencies can be expected to

resist the National Security Advisor during policy implementation.

On the other hand, in their role as policy advisor, National Security

Advisors must retain the confidence of the President by providing insightful

advice and orchestrating positive outcomes. There are so many

interdepartmental disagreements that the President cannot possibly

resolve them all, and the differences often reflect bureaucratic equities

rather than honest differences over alternative courses of action, which is

what the President needs and wants. If all the National Security Advisor

does is summarize department positions, he or she will be a disappointment

to the President. For this reason, advisors work hard to forge consensus

and integrate alternatives, sometimes at the expense of accurately

replicating department and agency positions, which causes friction with

Cabinet officials.

With the reforms recommended here, much of the tension between

the two advisor roles would disappear. Mission managers would integrate

alternative courses of action for consideration by the President and NSC

and implement the approved strategy. It would be the National Security

Advisor’s job to run the process and ensure that the President hears any

appeals from Cabinet officials to curb or overturn a mission manager’s

decision. For this purpose, the National Security Advisor could truly be an honest broker, ensuring that the mission manager, who is working the

issue full-time, and the Cabinet officials and their concerns are honestly

summarized for the President.

However, the new model of National Security Advisor also would have

system-wide duties and a system-wide perspective. The advisor would

have to ensure mission managers are set up for success and assess and

keep track of their progress. Finally, with the help of the NSC staff, they

would have to identify areas where mission managers are in conflict with

one another. All this would require a system-wide perspective. Instead

of concentrating on a handful of top Presidential priorities, the new National

Security Advisor would be responsible for ensuring the system as

a whole was working well and addressing the full range of critical issues.

This new model of National Security Advisor is much more practical.

Currently our expectations of National Security Advisors are altogether

unrealistic. We want them to be master administrators who advance the

multilayered interagency committee process in a timely, transparent, and

comprehensive fashion. But we also want them to be foreign policy and

national security maestros who combine a comprehensive appreciation

of the international system and security environment with a wide range

of subject matter expertise across an incredible array of multifarious,

complex problems that enables them to discreetly offer sagacious advice

when circumstances, or the President, demand it. Furthermore, we insist

that advisors have an exceptionally close and well-recognized personal

relationship with the President, essentially serving as the President’s alter

ego on national security.

National Security Advisors are criticized for not meeting these naive

expectations.34

National Security Advisor General James Jones, USMC

(Ret.), is a case in point. He was relentlessly attacked as inadequate despite

a successful career as a Service chief and the North Atlantic Treaty

Organization’s Supreme Allied Commander Europe. Leaks to the press

complained that he did not work himself into a state of utter exhaustion.

He was accused of being “too measured and low-key to keep pace with

the hard chargers working late hours in the West Wing”35 and of falling

behind “a White House on a manic dash to get a lot of top-tier issues

dealt with.”36 He was resented for biking at lunchtime, leaving after a

12-hour day instead of working late into the night,37 for missing key

meetings and, at the same time, not being by the President’s side all day

long.38

Jones was also criticized for managing collaboration rather than ensuring

his voice dominated debate on key issues. People complained

about Jones for “speaking up less in debates than [Secretary of State

Hillary] Clinton and not pushing as hard for decisions.”39 He was not seen as a dominant national security figure, but rather as self-effacing,

collaborative, and generous in meetings.40 He even sent others who were

substantively competent to meetings in his stead. One pundit observed,

“This kind of NSC collaboration always sounds good in principle [but]

when sharp disagreements arise . . . the self-effacing retired general may

have to summon his inner Henry Kissinger.”41 Even his admirers agreed

that “he needs to drive the agenda.”42

Finally, Jones was criticized as insufficiently close to the President.

The lack of a close, personal relationship with the President meant Jones

would not be taken seriously by other senior officials. One critic insisted,

“He has to be first among equals—the fact that Condi [Rice] couldn’t

control [Richard] Cheney and [Donald] Rumsfeld in [George W.] Bush’s

first term was disastrous. A lot depends on what sort of relationship develops

between Jones and [Barack] Obama.”43 Another expert worried,

“The National Security Advisor needs to be behind the president,” both

literally and figuratively, but General Jones is not “seen as the guy in the

room.”44 Pundits carped that other Presidential advisors had closer personal

relationships with President Obama, which put Jones at a major

bureaucratic disadvantage.

Critics were looking for an indefatigable subject matter genius and

bureaucratic warrior with close personal ties to the President to run the

national security system because that is just the kind of heroic individual

it would take to make our current system work minimally well. In

a system where only the President has the authority to compel collaboration,

critics wanted Jones to be an extension of the President and his

power. In a system where failures quickly gravitate to the White House

for centralized management, critics wanted Jones to be knowledgeable

enough to control the debate on all national security topics that came

his way. This kind of empowered subject matter maestro might improve

cross-departmental collaboration for a few issues, but the vast majority

will necessarily go unattended. This explains the criticism that Jones was

not working frantically enough. Without working around the clock (and

in the process exhausting intellectual capital rather than building it),

even fewer critical issues can be addressed.

The omnipresent, omniscient, and omnipotent National Security Advisor

does not exist and never has, and we should stop expecting one

to materialize. Instead we need someone who promotes collaborative

decisionmaking and less-centralized issue management and who understands

the importance of running the overall national security system

well. Jones’s admirers considered him a genius on management structures

and decisionmaking processes,45 and in a reformed system such

as the one advocated here, his approach would work admirably. If the President had the authority to designate mission managers, and a collaborative

Cabinet that understood and supported their use, a National

Security Advisor with Jones’s measured pace, attention to system-wide

performance, and collaborative bearing would serve the Nation and the

President well.

Conclusion

The 9/11 Commission’s report did a good job of identifying the major

limitations of the current national security system. It argued that “the

agencies are like a set of specialists in a hospital, each ordering tests,

looking for symptoms, and prescribing medications. What is missing

is the attending physician who makes sure they work as a team.”46 The

report explained this deficiency could not be rectified without adjusting

the authorities of Cabinet officials. However, the report did not recommend

circumscribing the authorities of Cabinet officials. Instead, the

commission, which only adopted recommendations with unanimous

support, advised in favor of creating the National Counterterrorism

Center, a new organization that would conduct planning but not make

policy or direct operations. As the Project on National Security Reform

noted, this recommendation was clearly inadequate to solve the problem

the commission identified:

Using the commission’s analogy of the different departments

and agencies acting like a set of specialists in a

hospital without an attending physician, we can say the

commission settled for a specialist who could offer a second

opinion without providing the attending physician

who directs the operations. Not surprisingly, to date the

departments and agencies have treated the National Counterterrorism

Center as a source for second opinions. The

reality is that all priority national security missions—not

just counterterrorism—require an attending physician.47

The recommendations in this chapter correct the shortcoming that

the 9/11 Commission identified but ignored. We do not need large, expensive,

new organizations and complex processes. We need legislation

from Congress, a President with a strong desire to improve national security

system performance, and a National Security Advisor with a collaborative

bent and organizational and bureaucratic acumen. Once in

place, the mission managers would prove effective and their use would

proliferate, which would require some additional follow-on reforms. Once mission managers demonstrate they can produce better outcomes,

additional reforms to help the system better support their use could be

implemented. The critical thing now—if we want a system capable of

significantly better performance—is to focus on these three indispensable

steps forward.

----

The author was the study director for the Project on National Security

Reform and its major report, Forging a New Shield (November 2008). He

would like to thank Jim Kurtz of the Institute for Defense Analyses for

multiple reviews of this chapter.

Notes

1 Douglas Stuart, “Constructing the Iron Cage: The 1947 National Security Act,” in

Affairs of the State: The Interagency and National Security, ed. Gabriel Marcella (Carlisle

Barracks, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, 2008), 53. See also Forging a New Shield (Washington,

DC: Project on National Security Reform, November 2008).

2 Ike Skelton, comments to the press, September 30, 2010, available at <http://armedservices.house.gov/pdfs/HR6249/SkeltonStatement.pdf>.

3 Christopher J. Lamb and Joseph C. Bond, National Security Reform and the 2016

Election, INSS Strategic Forum 293 (Washington, DC: NDU Press, April 2016).

4 A survey of over 250 books, articles, and studies on interagency cooperation in the

U.S. Government found only one report that concluded that interagency cooperation is

successful. See Christopher J. Lamb et al., “National Security Reform and the Security

Environment,” in Global Strategic Assessment 2009: America’s Security Role in a Changing

World, ed. Patrick M. Cronin (Washington, DC: NDU Press, 2009), 412–413. See also

Lamb and Bond.

5 Lamb and Bond.

6 Christopher J. Lamb and Edward Marks, Chief of Mission Authority as a Model for

National Security Integration, INSS Strategic Perspectives 2 (Washington, DC: NDU Press,

December 2010).

7 Richard Holbrooke, “The Machine That Fails,” Foreign Affairs, January 1, 1971,

available at <http://foreignpolicy.com/2010/12/14/the-machine-that-fails/>.

8 Harold Seidman, Politics, Position, and Power: The Dynamics of Federal Organization,

5th ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980), 219, 224.

9 Lamb and Bond, 2. The ineffectiveness of interagency committees was well explained

in Henry Jackson, Organizing for National Security: Inquiry of the Subcommittee on

National Policy Machinery, Senator Henry M. Jackson, Chairman, for the Committee on Government

Operations, United States Senate, 3 vols. (Washington, DC: Government Printing

Office, 1961).

10 Cited in Forging a New Shield, 260.

11 Ibid.

12 Lamb and Marks.

13 The term mission manager has gained some currency, and so it is used here. But as

some reviewers have noted, mission director would be a more appropriate title given the

authorities recommended for the position.

14 Title 10 U.S. Code, Section 162(b), available at <www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/10/162>.

15 Douglas J. Feith, War and Decision: Inside the Pentagon at the Dawn of the War on

Terrorism (New York: Harper, 2008), 316.

16 Title 10 U.S. Code, Section 162(b).

17 Lamb and Marks, 20.

18 Ibid., 18.

19 Ibid., 20ff. For an extended argument on this topic see Gordon Lederman, “National

Security Reform for the Twenty-first Century: A New National Security Act and

Reflections on Legislation’s Role in Organizational Change,” Journal of National Security

Law and Policy 3, no. 2 (February 2010).

20 Project for National Security Reform argued such legislation would need to be

accompanied by new Select Committees on National Security in the Senate and House of

Representatives with jurisdiction over all interagency operations and activities.

21 James R. Locher III, statement before the Senate Armed Services Committee, “30

Years of Goldwater-Nichols Reform,” November 10, 2015. Frank Ostroff makes the same

point in The Horizontal Organization: What the Organization of the Future Looks Like and

How It Delivers Value to Customers (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 12.

22 Ostroff, 12–13. Ostroff argues that employing cross-functional teams “without any

sense of how to ensure that the teams are working in an integrated way that advances the

performance of the entire entity, is nothing short of irresponsible.”

23 Ibid., 178.

24 Author conversations with a staff officer from U.S. Northern Command about his

strategy research project at the Army War College.

25 Conversation with a senior official in a Washington, DC–based think tank that

conducted an after-action report on the failed reforms for the U.S. Marine Corps.

26 As Ostroff states, “Performance trumps ideology,” and he provides much evidence

from both the private and public sectors. Ostroff, 159.

27 This is consistent with the organizational principle of “requisite variety.” “If a

business unit or team is to be successful in dealing with the challenges of a complex task,

it is vital that it be allowed to possess sufficient internal complexity.” See Gareth Morgan,

Images of Organization (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1997), 113.

28 There are several in-depth case studies of high-performing interagency national

security teams. See Christopher J. Lamb and Evan Munsing, Secret Weapon: High-Value

Target Teams as an Organizational Innovation, INSS Strategic Perspectives 4 (Washington,

DC: NDU Press, March 2011); Evan Munsing and Christopher J. Lamb, Joint Interagency

Task Force–South: The Best Known, Least Understood Interagency Success, INSS Strategic Perspectives

5 (Washington, DC: NDU Press, June 2011); Fletcher Schoen and Christopher

J. Lamb, Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency

Group Made a Major Difference, INSS Strategic Perspectives 11 (Washington, DC: NDU

Press, May 2012); and Christopher J. Lamb with Sarah Arkin and Sally Scudder, The

Bosnian Train and Equip Program: A Lesson in Interagency Integration of Hard and Soft Power,

INSS Strategic Perspectives 15 (Washington, DC: NDU Press, March 2014).

29 Numerous examples of this point are offered in Forging a New Shield and its 107

supporting case studies. Forging a New Shield, 160.

30 The Goldwater-Nichols Department of Defense Reorganization Act of 1986 has

such a right of appeal in Section 151, d, 1.

31 Frank G. Hoffman and G. Alexander Crowther, “Strategic Assessment and Adaptation:

The Surges in Iraq and Afghanistan,” in Lessons Encountered: Learning from the Long

War, ed. Richard D. Hooker, Jr., and Joseph J. Collins (Washington, DC: NDU Press,

2015).

32 Quoted in Ostroff, 131, 188.

33 For simplicity’s sake we will refer to the Assistant to the President for National

Security Affairs as the National Security Advisor.

34 See the discussion of complaints leveled against Condoleezza Rice in Christopher J.

Lamb with Megan Franco, “National-Level Coordination and Implementation,” in Lessons

Encountered: Learning from the Long War, 188, 198ff, 212ff.

35 Karen DeYoung, “National Security Adviser Jones Says He’s an ‘Outsider’ in Frenetic

White House,” Washington Post, May 7, 2009.

36 Steve Clemons, “Can James Jones Survive a Second Round of Attacks and ‘Longer

Knives’?” The Washington Note, June 12, 2009.

37 Helene Cooper, “Obama to Speak from Egypt in Address to Muslim World,” New

York Times, May 8, 2009.

38 Ben Smith and Jonathan Martin, “Reporters Jonesin’ for NSC Profiles,” Politico, May

8, 2009.

39 Mark Landler, “Her Rival Now Her Boss, Clinton Settles into New Role,” New York

Times, May 1, 2009.

40 Joe Klein, “Sizing Up Obama’s First 100 Days,” Time, April 23, 2009.

41 David Ignatius, “General James Jones’s Outlook as Barack Obama’s National Security

Adviser,” Washington Post, April 30, 2009.

42 Klein.

43 Ibid.

44 Cooper.

45 Clemons.

46 9/11 Commission Report. Interestingly, McChrystal uses the same analogy in his

recent book on teams. Stanley A. McChrystal, Tantum Collins, and David Silverman,

Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World (New York: Portfolio, 2015),

101–103.

47 Forging a New Shield.