DOWNLOAD PDF

World War I began on July 28, 1914, 1 month after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir-apparent to the Austro-Hungarian throne.1 Most Europeans expected the conflict to be short—“over by Christmas” was a common refrain—and relatively inexpensive in terms of blood and treasure. Almost immediately, however, the combatants faced each other in a long line of static defensive trenches. The Western Front quickly became a killing ground of unprecedented violence in human history: combined British, French, and German casualties totaled 2,057,621 by January 1915.2

The character of war had changed. Armies had not changed their battlefield tactics in response to new, highly destructive weapons, resulting in massive casualties. Rising calls from British political leaders, the media, and the public demanded action to break the stalemate. British strategists responded by opening a new front in the east with two strategic objectives: drive Turkey out of the war by attacking Constantinople, and open a route to beleaguered ally Russia.3 The decision to open a second front in the east in 1915 ultimately failed to achieve Britain’s strategic objectives during the first full year of World War I. British leaders pursued short-term, politically expedient military objectives in Turkey that were both ancillary to their military expertise and contrary to achieving the overall ends of winning the war by defeating Germany. This article examines the disastrous results of the attempt to open a second front and the disconnect between Allied strategic ends and means.

British battleship HMS Irresistible abandoned and sinking, having been shattered by explosion of floating mine in Dardanelles during attack on Narrows’ Forts, March 18, 1915 (Royal Navy/Library of Congress)

Genesis of the Dardanelles Decision

With combat in France and Belgium characterized by hopeless direct assaults on entrenched enemy positions, British strategists began planning for a new direction.4 First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill contemplated amphibious operations in the North Sea to increase pressure on Germany. He proposed a joint Anglo-French amphibious assault along the Belgian coast designed to outflank German positions on the Western Front, liberate the port of Zeebrugge, and prevent Germany from using Zeebrugge and Ostende as submarine bases.5 Ultimately, the British failed to convince the French to participate, effectively scuttling Churchill’s North Sea plan.

British political and military leaders next focused attention on Turkey and the possibility of military operations to seize the Dardanelles,6 attack Constantinople, and open a line of communication to Russia. Secretary of the War Cabinet Maurice Hankey, Chancellor of the Exchequer David Lloyd George, and Churchill advocated military operations against Turkey on the Gallipoli Peninsula.7 They agreed that the Ottoman Empire was weak and that “Germany [could] perhaps be struck most effectively, and with the most lasting results on the peace of the world through her allies, and particularly through Turkey.”8 Thus, within weeks of the outbreak of war, British attention turned east.

At the end of August 1914, Churchill formally requested that Secretary of State for War Field Marshal Herbert Kitchener organize a group of naval and military officers to plan for the seizure of the Gallipoli Peninsula, “with a view to admitting a British Fleet to the Sea of Marmara” and eventually knocking Turkey out of the war.9 Representatives of the War Office and the Admiralty met and concluded that an attack on the Gallipoli Peninsula was not a militarily feasible operation.10 Director of Military Operations Major General Charles Callwell11 presciently observed that a campaign in Gallipoli was “likely to prove an extremely difficult operation of war.”12 He proffered that an operation in the Dardanelles would require a force of not less than 60,000, with strong siege artillery, echeloned into Turkey in two large waves.13 Kitchener also disagreed with opening a second front, but for different reasons. He was reluctant to divert troops from the continent, which he viewed as the primary focus of effort for the British.

A dichotomy of opinion thus emerged: the politicians advocated for a second front on the Gallipoli Peninsula, while senior military officers argued against intervention in Turkey.14 The debate continued into winter. The dynamic changed on January 1, 1915, when Russia formally requested a “naval or military demonstration against the Turks to ease the pressure caused by the Turkish offensive driving through the Caucasus Mountains.”15 British decisionmakers debated the Russian request and the larger issue of the future strategic direction of the war effort during a series of War Council meetings in early January.16 The council decided that the British would continue to fight side by side with France on the Western Front, and the Admiralty would, commencing in February 1915, prepare operations “to invade and take the Gallipoli Peninsula, with Constantinople as its objective.”17

Bureaucratic maneuvering and negotiation were thus necessary to reach a decision to launch the operation. The next major task for senior British leaders was designing the strategy to implement the War Council’s decisions. The final plan would call for a combined force of six British and four French battleships, accompanied by a substantial naval escort, to push through the Dardanelles and fight to Constantinople.18

Flawed Assumptions Underpinning the British Strategy

The British designed their Dardanelles plan on a series of faulty assumptions. Political leaders and military planners alike assumed the Turks were deficient in martial skill, grit, and determination.19 Churchill displayed unbridled confidence in the ability of naval bombardment to destroy land targets.20 British war planners assumed that the battle fleet would easily breach the enemy’s coastal defenses, float directly to Constantinople, and seize the straits without requiring a landing force. Kitchener assumed that, once through the straits, with naval guns pointing at Constantinople, the fleet would “compel Turkey’s capitulation, secure a supply route to hard-pressed Russia, and inspire the Balkan states to join the Allied war effort and eventually to attack Austro-Hungary, thereby pressuring Germany.”21

Kitchener further assumed that once news of the arrival of the British fleet reached Constantinople, the entire Turkish army in Thrace would retreat, leaving Turkey to British control.22 Sir Edward Grey, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, argued that once the fleet moved through the Dardanelles, “a coup d’état would occur in Constantinople, whereby Turkey would abandon the Central Powers and join the Entente.”23 All of the foregoing assumptions proved false, and their cumulative effect foreordained the Dardanelles operation to disaster.

Australian troops charging near Turkish trench, just before evacuation at Anzac, ca. 1915 (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration)

Naval Operations in the Dardanelles

British naval forces shelled the forts at the entrance of the Dardanelles on November 1, 1914, well before the formal commencement of the Gallipoli campaign. The purpose of the attack was more to punish Turkey for siding with the Triple Alliance than an attempt to secure the strait. The shelling had a more pernicious effect, alerting the Turkish defenders that a future military operation in the Dardanelles by the British was likely. Mustafa Kamal Attaturk, overall Turkish commander at Gallipoli, and Otto Liman von Sanders, a German general and military advisor to Turkey, focused on fortifying the Dardanelles after the British attack of November 1.24 The Anglo-French naval force attacked the Dardanelles in force on March 18, 1915. The battle initially favored the attackers. Naval bombardment in the days preceding the assault successfully destroyed several Turkish defensive positions at the entrance to the straits.25 By midday, the British fleet neutralized most of the Turkish mines at the mouth of the Dardanelles, leaving nine more mine belts in the approach to Constantinople.26 The Clausewitzian concept of chance in war then emerged. The fleet approached an undetected line of 20 mines, which a Turkish steamer had laid just 10 days earlier.27 Three Allied warships struck mines and sank; a fourth suffered severe damage and was unsalvageable.28 The assumption that the Turks would surrender on sight of the British naval force was incorrect, and the prospect of a collapse of the Ottoman Empire by means of a naval assault alone died on March 18. The setback caused the British War Council to delay further naval action immediately.

The council charted a new course and called for landing troops in a beach-hopping campaign from the Aegean to the Sea of Marmara, eventually attacking Constantinople.29 However, 38 days would pass before British commanders were able to embark, transport, and land military forces on the peninsula. In the interim, the enemy seized the initiative. Turkey deployed six divisions, some 500 German advisors, and civilian labor units in a hurried effort to strengthen Gallipoli’s defenses in anticipation of the next round of fighting.

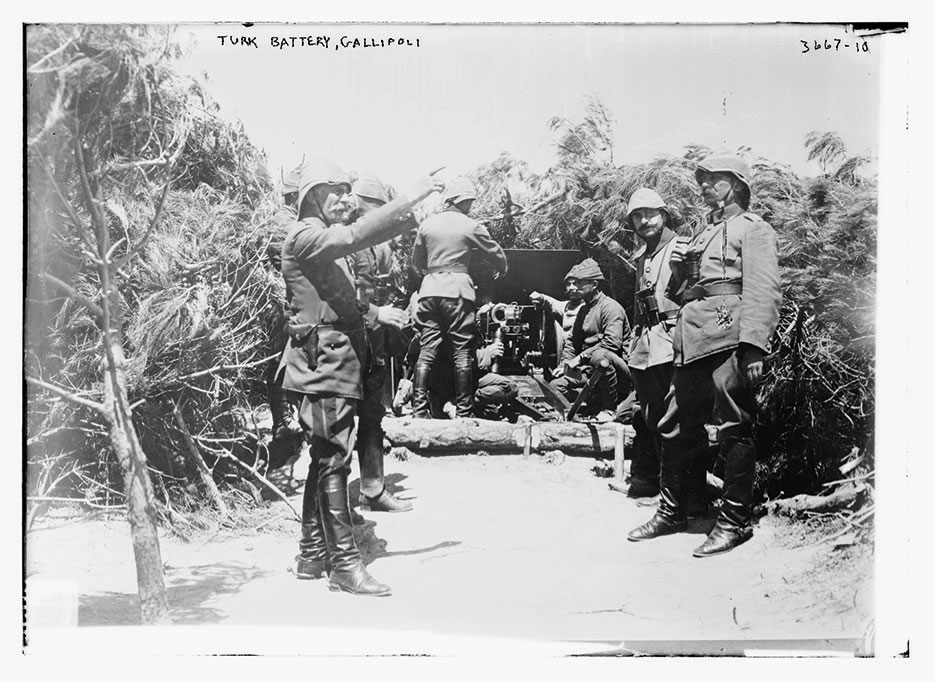

Ottoman soldiers and guns during Gallipoli campaign (Library of Congress)

Amphibious Landings on Gallipoli

The British did not reassess their strategic objective of defeating Turkey and opening a line of communication with Russia after the failure of the naval attack. In fact, the historical record shows just the opposite: British leaders redoubled their efforts, eventually committing nearly 500,000 Allied forces to the Gallipoli operation. Kitchener appointed General Sir Ian Hamilton as the overall commander of a combined force of British, Australian, New Zealander, and French troops. Hamilton faced a challenge of epic proportions. His task was to conduct the first opposed amphibious landing in an era of high-powered defensive weapons that included innovations such as the machine gun and highly accurate artillery firing a new generation of high explosives.30

At dawn on April 25, 1915, British, Dominion, and Allied forces waded ashore onto six landing beaches at Cape Helles.31 Amphibious operations continued for 8 months, but the Allies never gained more than a foothold on the peninsula. The campaign to outflank the stalemate on the Western Front ironically began to resemble the fighting in France and Belgium, although on a much smaller scale, with Hamilton committing his troops against an entrenched and forewarned foe at Gallipoli.32 Although Kitchener and Hamilton recognized that a central assumption about the Turks—that they were a second-rate fighting force that did not stand a chance against British arms—was clearly wrong, they did not change course.33 In fairness to British military commanders, a major reason for continuing the operation was political expediency.34 David Fromkin observes, “Constantinople and the Dardanelles, because of their world importance for shipping, and eastern Thrace, because it is in Europe, were positions that occupied a special status in the minds of British leaders.”35 As Churchill further argued, “the line of deep water separating Asia from Europe was a line of great significance, and we must make that line secure by every means within our power.”36

Despite the perceived importance of the region to British war aims, the Allies withdrew from the peninsula on January 9, 1916, dashing hopes of defeating Turkey and reaching the Russians. British, Australian, New Zealander, and French casualties totaled 130,000, yet the operation achieved none of the goals set by British political leaders.

Mismatch of Ends and Means

The British experience in the Dardanelles is a cautionary tale that highlights the flaws inherent in a strategy characterized by improperly aligned ends and means.37 The initial plan—a navy-only effort to forcibly enter the Dardanelles, navigate the peninsula while destroying land-based targets with surface fires, and force the capitulation of Constantinople—is perhaps the classic example of imbalanced ends and means in World War I. Naval gunfire in 1915 was generally ineffective against land-based artillery and even static targets without ground-based spotters.38 Although the fleet had limited success in the opening days of the naval operation, decisively defeating Turkish defensive positions in the 35-mile-long strait with naval guns alone was not feasible. Furthermore, ships are by definition incapable of taking land and occupying terrain. In fact, neither Kitchener nor Hamilton had any sustainable plan to seize and hold terrain in March 1915.

Another example of mismatched ends and means occurred in the minesweeping phase of the first attack in Gallipoli. The Allied fleet “applied its least capable set of assets, that of fishing trawlers turned minesweepers manned by civilian crews, against the most difficult part of the campaign, that of clearing mines under fire.”39 Even the amphibious landings of April 25 lacked properly balanced ends and means. A total of five British, French, and Commonwealth divisions landed at five separate beaches against entrenched defenders expecting an Allied attack.40 Although the number of forces in action in the Dardanelles consistently grew during the evolution of the operation, the fact remains that the Allies never successfully held a beachhead for an extended period, largely due to the lack of means, that is, ground forces.

Another imbalance in the ends-means paradigm was evident in British command and control. Inadequate command and control

handicapped Hamilton throughout the campaign, but was especially evident during the first, crucial days of the landing. Hamilton monitored the landing from aboard the Queen Elizabeth. . . . [However], the Queen Elizabeth was not configured as a headquarters for an amphibious task force. As a result, Hamilton’s staff, what could be fitted aboard the Queen Elizabeth, was squirreled away throughout the ship.41

The commander of one of the largest, most complex amphibious assaults in history was thus virtually powerless to exert his will over his own forces, let alone those of the enemy. Without the means to command and control a complex military operation, the ends were all but unattainable.42 A lack of two further means—amphibious doctrine and previous army-navy joint training—also hindered Hamilton’s ability to orchestrate the landings.43 The Clausewitzian concept of friction, compounded by the lack of command and control, amphibious doctrine, and previous army-navy training, took effect on the battlefield almost immediately. The historical record is replete with first-hand accounts of problems exacerbated by weak command and control. An Australian soldier succinctly described a frustrating scene undoubtedly unfolding for thousands of men during the Gallipoli campaign: “Battalions dissolved into separated groups of men, some making marvelous progress but without possibility of any support. It was this and the strengthening Turkish resistance which led to the disturbing lack of confidence by commanders, who felt that the men should be evacuated.”44

Helmuth von Moltke the Elder, chief of the Prussian General Staff from 1857 to 1887, observed, “Strategy can direct its efforts only toward the highest goal that the available means make practically possible.”45 British means in the Gallipoli campaign did not support British strategy. The imbalance between ends and means in the naval and ground campaigns in the Dardanelles doomed the overall effort to failure.

Conclusion

The changing character of war, embodied in the deadly intersection of 19th-century tactics and 20th-century weapons, created a staggering number of casualties in 1914. The carnage prompted British leaders to seek a new front to break the European stalemate. Strategists looked east to open a new theater of war. The plan to conduct operations against Turkey and open a route to Russia suffered from flawed assumptions, which led first to an ill-advised, naval-only attack in the Dardanelles. Six weeks later, this time without the element of surprise, the Allies attacked again. The second round featured a larger naval fleet with an embarked landing force of five divisions. A series of amphibious landings over the next 8 months, however, failed to gain anything more than a foothold for the Allies. The British lacked the means to achieve the desired ends in the Dardanelles, particularly in the command and control, doctrinal, training, and manpower realms. The Allies ultimately failed in their attempt to seize the Dardanelles, force Constantinople’s surrender, and open a link with their Russian ally. In the final analysis, a flawed strategy, poorly executed, did not achieve Allied ends.46

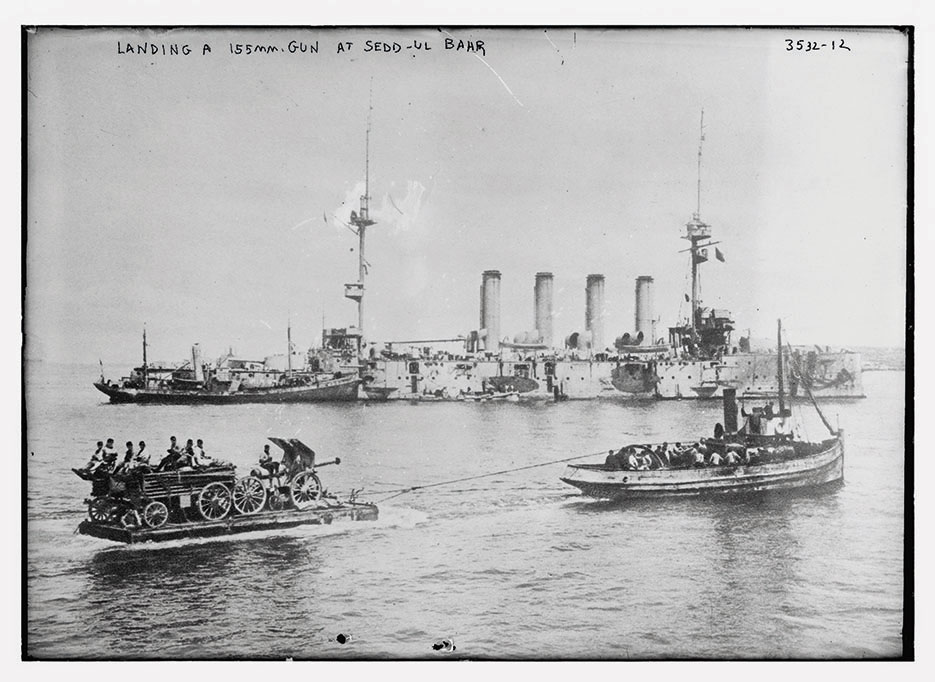

Warships near Gallipoli Peninsula landing 155-mm gun at Sedd-ul Bahr (Library of Congress)

Coda: Lessons Learned on Amphibious Assault

The Dardanelles campaign was a disaster for Great Britain. Amphibious assaults against defended beachheads, among the most challenging of military operations, were widely considered impossible after the failed Gallipoli landings. The seemingly overwhelming challenges presented by amphibious assaults—in command and control, amphibious operations doctrine (or lack thereof), interservice coordination, and maintaining a beachhead after landing—convinced military and political leaders of the futility of operational maneuver from the sea. However, as Clausewitz observed, “Historical examples clarify everything and also provide the best kind of proof in the empirical sciences. This is particularly true in the art of war.”47

During the interwar years, military planners and theorists validated the Clausewitzian concept of the value of studying history. Planners and theorists analyzed the reasons for the failure in the Dardanelles and developed doctrine, conducted exercises, and structured forces to overcome the problems associated with successfully assaulting fortified coastal defensive positions. A generation after Gallipoli, the Allies successfully landed tens of thousands of troops on beaches defended by entrenched and well-equipped German and Japanese forces. Allied amphibious operations in North Africa, Europe, and the Pacific were instrumental in the combined effort to defeat Nazism and Japanese imperialism.

Another lesson to emerge from Gallipoli, despite failure there, was the importance of the indirect approach, which factored heavily into British strategy during World War II. Churchill favored amphibious operations against Germany in the North Sea in 1914 in an effort to bypass the main line of resistance on the Western Front. Less than three decades later, Churchill opposed the U.S.-favored Operation Roundup, a cross-channel attack planned for mid-1942. The prime minister instead advocated for operations in North Africa, Italy, and the Balkans—presumably softer targets than Adolf Hitler’s Atlantic Wall—before a cross-channel assault against Fortress Europe.

Finally, Churchill personifies the greatest legacy of the Gallipoli campaign. A primary architect of the Dardanelles disaster, he managed to salvage his reputation and career after Gallipoli, and emerged as one of the most effective war leaders in history during World War II. The lessons of Gallipoli, learned at great cost in blood and materiel, were thus not in vain. JFQ

Notes

- Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy forged the Triple Alliance in May 1882. France, Britain, and Russia formed the Triple Entente in 1907 in an attempt to balance the growing German threat as Berlin’s economy and military grew in the early 20th century. Members of the Triple Alliance were bound to defend each other through force of arms; Triple Entente members had a “moral obligation” to defend each other. A critical event occurred on August 2, 1914, when the Ottoman Empire signed a secret treaty joining the Triple Alliance. See Hew Strachan, ed., The Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 10–11; U.S. Department of State, Catalogue of Treaties: 1814–1918 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1919), 11; “The Road to War: The Triple Entente,” BBC Schools, available at <www.bbc.co.uk/schools/worldwarone/hq/causes2_01.shtml>.

- Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire during the Great War (London: His Majesty’s Printing Office, 1922), 237–252.

- Russia suffered stinging losses soon after the outbreak of hostilities, particularly in the Battle of Tannenberg against Germany. The British feared a Russian collapse and thus sought to relieve pressure on the tsar by attacking through the Dardanelles to reach Russia.

- David Fromkin, A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1989), 124.

- Ibid.

- The Dardanelles Strait is 35 miles in length. The entrance is 2.5 miles wide. It extends for 4 miles in a northeasterly direction, widens to a maximum width of 4.5 miles, and then narrows to less than a mile. The narrows extend for 4 miles, then widen again to 3 miles. They continue for another 20 miles before entering the Sea of Marmara. This geographic information is from Victor Rudenno, Gallipoli: Attack from the Sea (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 27.

- Fromkin, 125.

- Ibid.

- Graham T. Clews, Churchill’s Dilemma: The Real Story Behind the Origins of the 1915 Dardanelles Campaign (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2010), 44.

- Ibid.

- Charles E. Callwell was an influential military theorist. He published a seminal work on counterinsurgency titled Small Wars: Their Principles and Practice (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1899).

- Trumbull Higgins, Winston Churchill and the Dardanelles: A Dialogue in Ends and Means (New York: Macmillan, 1963), 57.

- Ibid.

- Fromkin, 127, observes, “The doctrine of the generals was to attack the enemy at his strongest point; that of the politicians was to attack at his weakest.” This “politicians’ predilection” for attacking at the enemy’s weakest point would surface again in World War II.

- Peter Hart, Gallipoli (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 14.

- Ibid., 16.

- As quoted in ibid.

- Martin Gilbert, A History of the Twentieth Century, Volume One: 1900–1933 (New York: Avon Books, 1997), 63.

- Hart, 22.

- Clews, 37.

- Gilbert, A History of the Twentieth Century, 363.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Rudenno, 12–13.

- Martin Gilbert, The First World War: A Complete History (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1994), 136.

- Gilbert, A History of the Twentieth Century, 365.

- Gilbert, The First World War, 136.

- Clews, 275.

- Gilbert, A History of the Twentieth Century, 365.

- Hart, 171.

- Fromkin, 157. The historical record is replete with accounts of heroism and suffering on both sides. However, a detailed account of the fighting at the tactical level is not within the scope of this article.

- Ibid., 561.

- The concept of sunk cost applies in the Gallipoli campaign. The theory behind the sunk cost concept is that in a failing endeavor, such as Gallipoli, the decisionmaker justifies continued expenditure in an effort to recoup past losses.

- British decisionmaking in the Gallipoli campaign is a classic example of the Rubicon theory of war. Under this theory, “when people believe they have crossed a psychological Rubicon and perceive war to be imminent, they switch from what psychologists call a ‘deliberative’ to an ‘implemental’ mind-set, triggering a number of psychological biases, most notably overconfidence.” This theory helps explain why, even when the commanders realized their central assumptions about Gallipoli were wrong, British political and military leaders made no change in the overall course of the Dardanelles strategy. Information concerning the Rubicon theory of war is from Dominic D.P. Johnson and Dominic Tierney, “The Rubicon Theory of War: How the Path to Conflict Reaches the Point of No Return,” International Security 36, no. 1 (Summer 2001), 7–40.

- Fromkin, 548–549.

- As quoted in ibid., 549.

- Carl von Clausewitz devoted a significant amount of discussion to the importance of properly linking ends and means in strategy. See Carl von Clausewitz, On War, trans. and ed. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984), 127–147, et seq.

- Jonathan Schroden, “Strait Comparison: Lessons Learned from the 1915 Dardanelles Campaign in the Context of a Strait of Hormuz Closure Event,” Center for Naval Analyses, September 2011, available at <www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/s/strait-comparison-lessons-learned-from-1915-dardanelles-campaign.html>.

- Ibid.

- Philip J. Haythornthwaite, Gallipoli, 1915: Frontal Assault on Turkey, Osprey Military Campaign Series 8 (London: Osprey, 1991), 45.

- Gregory A. Thiele, “Why Did Gallipoli Fail? Why Did Albion Succeed? A Comparative Analysis of Two World War I Amphibious Assaults,” Baltic Security and Defence Review 13, no. 2 (2011), 139.

- The ends were successful penetration of the Dardanelles, landing and sustaining assault forces on well-defended beaches, and forcing the surrender of the capital city of an empire.

- Thiele, 150.

- Peter H. Liddle, Gallipoli 1915: Pens, Pencils and Cameras at War (London: Brassey’s Defence Publishers, Ltd., 1985), 45.

- Grand [German] General Staff, trans. A.G. Zimmerman, Moltke’s Military Works: Precepts of War (Newport, RI: U.S. Naval War College, 1935), Part II, 1.

- Churchill lost his post as the First Lord of the Admiralty and Hamilton lost his command in the aftermath of Gallipoli. The conclusions of the Gallipoli Commission, which inquired into the circumstances of the failed military operation, are available at <www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ pathways/firstworldwar/transcripts/battles/dardanelles.htm>.

- Clausewitz, 170.