ABSTRACT

Sun Tzu permeates modern Chinese strategy, influencing everything from deception to espionage while downplaying civilian control in favor of a general’s on-site decisions and pushing “initiative, resulting in a Chinese Air Force inclination to take this initiative through offensive operations and raising the specter of Beijing developing a preemptive strategy despite protestations that the national defense policy is “purely defensive in nature.” Countering Chinese strategy calls for using Sun Tzu against Beijing. For example the general enshrined moral influence to bring the people in line with their leaders’ vision. That can be undermined through an exposé of the leaders’ real lives versus the fable and other discrepancies between public posturing and private actuality.

Sun Tzu wrote 2,500 years ago during an agricultural age but has remained relevant through both the industrial and information ages. When we think about security, Japan’s greatest strategic concern is China, and we cannot discuss Chinese strategy without first discussing Sun Tzu. In this article, I demonstrate how contemporary Chinese strategists apply the teachings of Sun Tzu and his seminal The Art of War.1

Statue of Sun Tzu in Yurihama, Tottori, Japan

Why Sun Tzu?

Europe first discovered Sun Tzu during the late 18th century. Wilhelm II, the emperor of Germany, supposedly stated, “I wish I could have read Sun Tzu before World War I.” General Douglas MacArthur once stated that he always kept Sun Tzu’s The Art of War and Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass on his desk. At the end of the Cold War, the United States borrowed from Sun Tzu when it created “competitive strategy,” which aimed to attack the Soviets’ weaknesses with American strengths.2 This is exactly Sun Tzu’s meaning when he said an “Army avoids strength and strikes weakness.” I have also heard that this idea is referred to as a “net assessment” strategy in the Pentagon.

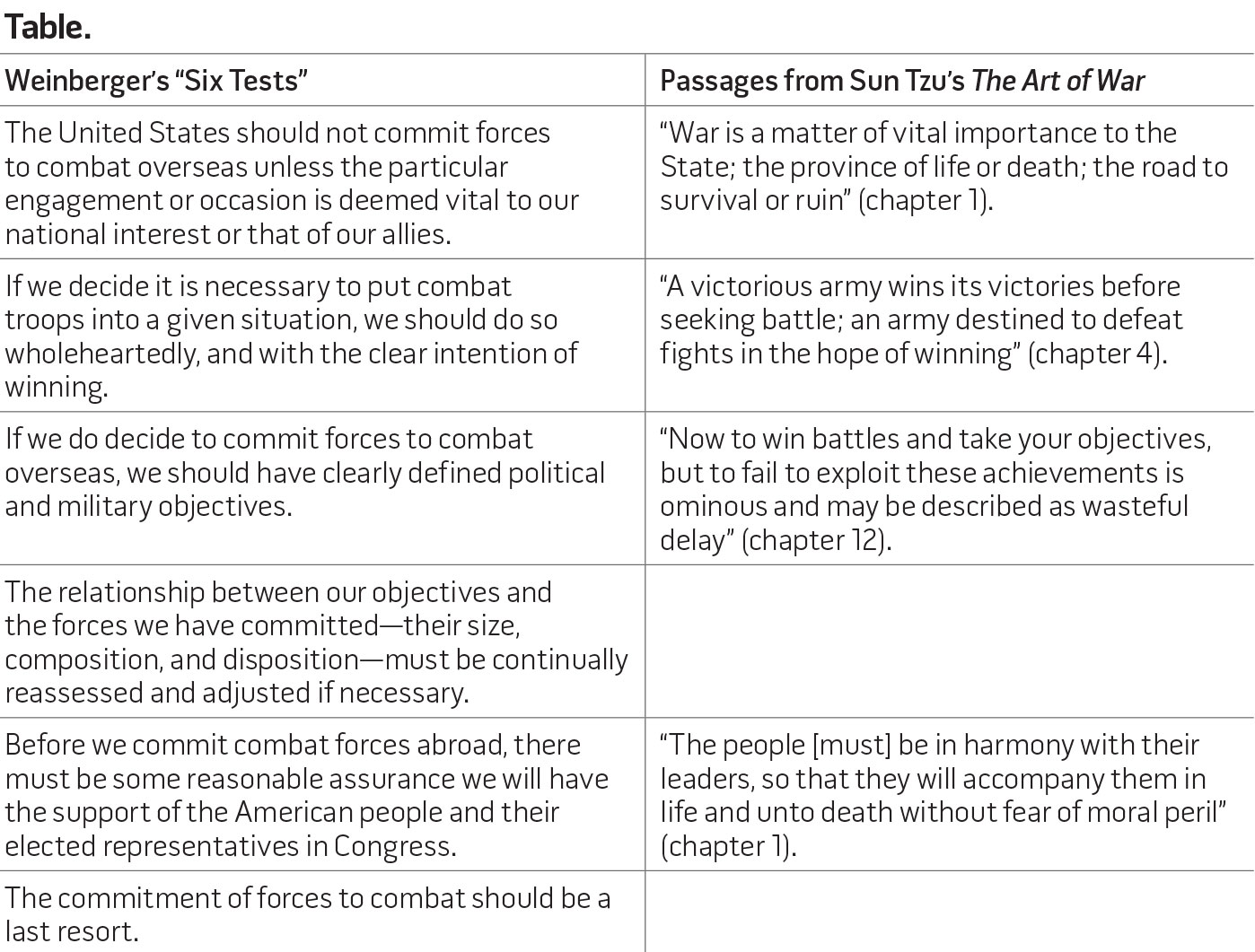

When I was a student at the National Defense University in Washington, DC, I studied Caspar Weinberger’s “six tests.” When I first considered his tests I immediately thought, “This is the teaching of Sun Tzu.” Let us consider Weinberger’s six tests and the comparable ideas found in The Art of War (see table).

General Colin Powell added a few tests of his own with the so-called Powell Doctrine, and his tests also have comparable passages in Sun Tzu. For instance, Powell’s questions “Is there a plausible exit strategy to avoid endless entanglement?” and “Have risks and costs been fully and frankly analyzed?” are similarly mentioned in chapter 2 of The Art of War.

Contemporary Chinese Strategy

In 2001 I had some conversations with General Xiong Guankai, deputy chief of staff in Beijing. When I offered a phrase from Sun Tzu in conversation, the general recited the whole passage in Sun Tzu. I also visited the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) National Defense University (PLANDU), the highest educational institute for the Chinese military, and asked the vice president how PLANDU teaches Sun Tzu. He answered that the ancient strategist is the centerpiece of the curriculum. According to the Chinese Information Bureau in 2006, the PLA decided to use The Art of War as the educational textbook not only for officers but also for all enlisted soldiers and sailors.

When I was invited by the PLA University of Science and Technology (PLAUST) to the Symposium for Presidents of Military Institutions in October 2011, I spoke to the president of PLAUST during the symposium. Whenever I mentioned a phrase from Sun Tzu’s writing, he too responded with the entire passage. He had memorized the strategist’s work.

I also had an opportunity to visit the PLA Army Command Academy in Nanjing where the academy’s motto from a passage in chapter 5 of The Art of War appears on the library wall: “Use the normal force to engage; use the extraordinary to win.” An American scholar pointed out that the Chinese concept of cyber attack is based on that phrase.3 There were other framed phrases from Sun Tzu in the library: “All warfare is based on deception,” and “There are strategist’s keys to victory. It is not possible to discuss them beforehand.”

A phrase of Deng Xiaoping’s 24-Character Plan (“Hide our capabilities and bide our time”), which was a central tenant of Chinese strategy since the Tiananmen Square incident in 1989, is derived from Jiang Ziya’s The Six Secret Teachings on the Way of Strategy, one of China’s seven military classics. Some of Mao Zedong’s characteristics of strategic secrets, such as “When an enemy advances, we will retreat,” “When an enemy stays, we will disturb them,” “When an enemy is tired, we will strike them,” and “When an enemy retreats, we will chase them” are very similar to Sun Tzu’s “When he concentrates, prepare against him; where he is strong, avoid him. Attack where he is unprepared; sally out when he does not expect you” (The Art of War, chapter 1).

Since all Chinese military personnel seem to memorize Sun Tzu, it is possible that Chinese strategy is based on The Art of War. All Central Military Commission members except Xi Jinping are generals and admirals who have memorized his work completely. Even though PLA weapons and tactics are not as sophisticated as those of the major Western powers, this comprehensive strategy—which includes nonmilitary means—is clever, and we must understand how China has adopted Sun Tzu for its contemporary strategy.

What is Chinese contemporary strategy? It is not necessarily revealed in China’s National Defense, which is published every 2 years. In the preface we read, “China will never seek hegemony.”4 According to reports by the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments and RAND, by 2020 China will be well on its way to having the means to achieve its first–island chain policy. In May 2013 Chinese newspapers discussed possession of Okinawa. In 2012 a PLA think tank, the Military Science Academy, advocated a “strong military strategy” that insists that the PLA Navy must protect national interests west of 165 East and north of 35 South. On its maps, China portrays a three-line configuration that includes the Hawaiian Islands as the third–island chain.

In 2012 a Chinese delegation insisted on Hawaiian sovereignty to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. Admiral Timothy Keating, commander of U.S. Pacific Command, was approached in 2007 by a Chinese admiral who advocated dividing the Pacific. Due to the declaration that “China will never seek hegemony,” Chinese strategy is clearly deceptive. We have to look at their real intentions. The latest China’s National Defense emphasizes “rapid assaults.”5 Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2013 also states that the “PRC continues to pursue [the ability] to fight and win short duration [conflicts].”6 This is contextually similar to “while we have heard of blundering swiftness in war, we have not yet seen a clever operation that was prolonged,” which is found in chapter 2 of The Art of War.

“Three Warfares”

In 2003 the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee and the Central Military Commission endorsed the “three warfares” concept, reflecting China’s recognition that as a global actor it would benefit from learning to use the tools of public opinion, particularly during the early stages of a crisis, as these tools have a tendency to bolster one another.7 The PLA issued 100 examples each for psychological, media, and legal warfare. Psychological warfare examples cited Sun Tzu 30 times, media warfare examples cited him 6 times, and legal warfare examples cited him 3 times. The most cited phrase (from chapter 3) is “To subdue the enemy without fighting is the acme of skill,” which appears 10 times. The next most repeated phrase (from chapter 1) is “All warfare is based on deception,” appearing half a dozen times.

The PLA Daily reported that when 10 warships, including 2 Kilo-class submarines, passed through the Miyako Strait, they were to conduct exercises in the spirit of the three warfares concept. As it is not possible to conduct media and legal warfare as part of a naval exercise, we should understand that they conducted psychological warfare with the goals of the deterrence, shock, and demoralization of Japan.

Chinese leaders typically mention ideas such as “Chinese Military Buildup No Threat to the World” (Defense Minister Liang Guanglie’s statement in November 2012), or “Peaceful Development” (China’s National Defense), or “Harmonious Ocean” (the theme of the PLA Navy’s multinational naval event in 2009). All of these are examples of media warfare or, in other words, propaganda. On March 8, 2013, the People’s Daily reported that the sovereignty of the Ryukyu Islands is historically pending and not yet determined. This is still another example of media warfare. To Beijing, the Ryukyu Islands must represent “key ground, ground equally advantageous for the enemy or me to occupy” (chapter 11, The Art of War) because the North and East Sea Fleets can pass through the area into the Pacific with impunity. However, as Sun Tzu stated, “Do not attack an enemy who occupies key ground.” China has instead supported Okinawa’s independence activities, which were developed by pro-Chinese Okinawans and probably Chinese secret agents as well.

Moreover, Beijing has legislated many internal maritime laws to justify its maritime activities including:

- Law of the People’s Republic of China Concerning the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone (1992)

- Proclamation of Territorial Base Line (1996)

- Public Relation Marine Science Research Administrative Regulation (1996)

- Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Exclusive Economic Zone and the Continental Shelf (1998)

- Marine Environment Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China (1999)

- Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Administration of the Use of Sea Areas (2001)

- Desert Island Protection Usage Administrative Regulation (2003)

- Law of the People’s Republic of China on Island Protection (2009)

- National Mobilization Law (2010)

- Maritime Observation Forecast Administrative Regulations (2012).

Disintegration Warfare

The PLA International Relations Academy in Nanjing studied disintegration warfare from 2003 to 2009. Then in 2010 a PLA publisher issued Disintegration Warfare. A passage from chapter 3 of The Art of War, “To subdue the enemy without fighting is the acme of skill,” appears on the cover of Disintegration Warfare. The idea of disintegration warfare includes politics, economy, culture, psychology, military threats, conspiracy, media propaganda, law, information, and intelligence. All these concepts are clearly building on Sun Tzu’s ideas of deception, disruption, and subduing the enemy without fighting.

In 2012, for the first time since its establishment, the Minister of Foreign Affairs Conference of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was not able to announce a joint communiqué because China had given tremendous economic aid to Cambodia, the chair country of the conference. The tighter coordination of ASEAN over the issue of the South China Sea does not favor China. Therefore, China resorted to disintegration warfare to try to disrupt the ASEAN alliance by using economic manipulation. China has implemented many methods, including historic issues during World War II, in attempts to divide the United States and Japan as well.

Unrestricted Warfare

In 1999 two PLA colonels, Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui, published the book Unrestricted Warfare, which changed the definition of unrestricted warfare from “using armed force to compel the enemy to submit to one’s will” to “using all means, including armed force or non-armed force, military and non-military, and lethal and non-lethal means to compel the enemy to accept one’s interests.”8

Non-armed force includes trade war, financial war, a new terror war, and ecological war.9 As for trade war, China banned rare-earth mineral exports to Japan after a Chinese fishing boat skipper was arrested near Senkaku in September 2010. In October 2010, when Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, Beijing reduced its imports of salmon from Norway. China also reduced banana imports from the Philippines when the two countries clashed over Scarborough Shoal in 2012.

Chinese bamboo copy of The Art of War with cover inscription suggesting it was either commissioned or transcribed by Qianlong Emperor (UC Riverside)

In part two of the book A Discussion of New Methods of Operation, Qiao and Wang cite Sun Tzu: “As water has no constant form, there are in war no constant conditions. Thus, one able to gain victory by modifying his tactics in accordance with the enemy situation may be said to be divine” (The Art of War, chapter 6). Before this passage, there is the famous phrase: “An army avoids strength and strikes weakness.” This is the substance of unrestricted warfare. Western militaries rely on information systems such as computer networks and space surveillance. Beijing wants to attack those weaknesses using cyber strikes as soft means and antisatellite weaponry as hard means.

The U.S. Secretary of Defense’s annual report to Congress, Military Power of the People’s Republic of China (2009), stated that China’s leaders stress asymmetric strategies to leverage their advantages while exploiting the perceived vulnerabilities of potential opponents using so-called “assassin’s mace” programs (for example, counterspace and cyber warfare programs).10

Intelligence Warfare

There are strategic documents other than Sun Tzu’s that include the topic of intelligence. Carl von Clausewitz’s On War has only a few pages mentioning intelligence. He writes, “In short, most intelligence is false.”11 B.H. Liddell Hart’s Strategy perhaps intentionally has no discussion of intelligence at all. Sun Tzu spends the entire last chapter of The Art of War discussing intelligence.

Sun Tzu identifies five types of secret agents. The first is the native of the enemy’s country. There is no doubt that countering the native agent is important for antiterrorism warfare. David W. Szady, a former assistant director for the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), stated, “the Chinese . . . mastered the use of multiple redundant collection platforms by looking for students, delegates to conferences, relatives and researchers to gather information.”12

The second secret agent is the one inside the organization. The Art of War states, “Of old, the rise of Yin was due to I Chih, who formerly served the Hsia; the Chou came to power through Lu Yu, a servant of the Yin.” Paul D. Moore, the former FBI chief Chinese intelligence analyst, writes, “Some Americans of Chinese ancestry in sensitive research or defense-related positions now feel themselves to be under increased scrutiny as security risks.”13

The third secret agent is the double agent. Katrina Leung provides a good example. A former high-value FBI and PRC Ministry of State security agent, Leung allegedly contaminated 20 years of intelligence relating to the PRC as well as critically compromising the FBI’s Chinese counterintelligence program. In March 2013 Bryan Underwood, a former civilian guard at a U.S. consulate compound under construction in China, sold classified photographs, information, and access to the U.S. consulate to the Ministry of State Security.14

The fourth secret agent is the expendable type. Sun Tzu states that expendable agents are friendly spies who are deliberately given fabricated information (disinformation) that is related to the media warfare aspect of the three warfares concept. In September 2012 the Global Times reported the result of the March 2006 referendum of Ryukyu citizens. Seventy-five percent of them supported independence from Japan and reinstating free trade with China, and 25 percent supported remaining part of Japan.15 There was in fact no referendum by Ryukyu citizens, and the vast majority of Okinawans want to be a part of Japan. This is a typical example of Chinese disinformation.

The last type of secret agent is the living agent, who collects information and returns with it. Most living agents today engage in cyber espionage. The U.S. Office of the National Counterintelligence Executive published the Counterintelligence Report (2011), which states, “Chinese actors are the world’s most active and persistent perpetrators of economic espionage.”16 The U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission reported in 2009 that “U.S. industry and a range of government and military targets face repeated exploitation attempts by Chinese hackers as do international organizations and nongovernmental groups including Chinese dissident groups, activists, religious organizations, rights groups, and media institutions.”17 Despite the fact that Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China (2013) listed six specific names of spies,18 the Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesman denied China’s involvement with cyber espionage. During the U.S.-China Defense Summit in August 2013, Minister of Defense General Chang Wanquan denied (unpersuasively) that China was a major source of pervasive global computer hacking. It has long been acknowledged that China is the greatest source of cyber attacks against the West.19 That is exactly what Sun Tzu meant when he wrote, “When active, feign inactivity.”

Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force destroyer JS Kurama under way with Arleigh Burke–class guided-missile destroyer USS <em>Gridley</span> during passing exercise (U.S. Navy/James R. Evans)

Conclusion

Contemporary Chinese strategy is heavily influenced by Sun Tzu, emphasizing everything from deception, which we find in chapter 1, to espionage, which we read about in chapter 8.

There are two final concerns. First, Sun Tzu ignores so-called civilian control. He writes, “There are occasions when the commands of the sovereign need not be obeyed” (chapter 8), and “If the situation is one of victory but the sovereign has issued orders not to engage, the general may decide to fight” (chapter 10). We have seen many indications of this including the Han-class nuclear submarine’s intrusion into Japanese territorial waters in November 2004, the antisatellite weapon test in January 2007, and the revelation of the J-20 stealth fighter when Secretary of Defense Robert Gates visited China in January 2011.

Second, the main theme of the first half of chapter 6 of The Art of War is “initiative.” China has made preemptive strikes since its establishment, such as in the Korean War in 1950; the Strait crises in 1954, 1958, and 1995–1996; against India in 1962; against the Soviet Union in 1969; and against Vietnam in 1974 (Paracel Islands), 1979, and 1988 (Spratly Islands). The first principle of the Chinese Air Force is securing initiative through offensive operations.20 The Military Power of the People’s Republic of China (2007) contained a side column that asked, “Is China Developing a Preemptive Strategy?”21 But China’s National Defense (2008) stated, “China pursues a national defense policy which is purely [deleted since the 2010 version] defensive in nature.”

What should we do for countering Chinese strategy? We have to know and use Sun Tzu against China. The general stated, “The first five of the fundamental factors is moral influence which causes the people to be in harmony with their leaders” (chapter 1). In order to disintegrate Chinese moral influence, we must reveal its leaders’ true activities as the New York Times did in October 2012 when it reported that Wen Jiabao’s relatives had tremendous financial assets in the United States. This news damaged the legitimacy of the Communist Party. As a result, the PLA cyber force wanted to discredit the article by all means.

Sun Tzu’s The Art of War is a double-edged sword. It is effective for opponents but may boomerang on its users. “He who is not sage and wise, humane and just, cannot use secret agents” (chapter 8). JFQ

Notes

- Sun Tzu, The Art of War, trans. Samuel B. Griffith (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1963).

- United States Military Posture for FY1989 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1989), 5–6, 93–94.

- J.P. London, “Made in China,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 137, no. 4 (April 2011), 59.

- China’s National Defense 2012 (Beijing: Ministry of Defense, 2013), preface.

- Ibid., chapter 2.

- Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD), Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2013 (Washington, DC: OSD, 2013), i.

- OSD, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2011 (Washington, DC: OSD, 2011), 26.

- Colonel Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui, Unrestricted Warfare (Beijing: PLA Literature and Arts Publishing House, February 1999), preface.

- Ibid., chapter 2.

- OSD, Annual Report to Congress: Military Power of the People’s Republic of China 2009 (Washington, DC: OSD, 2009), 20.

- Victor M. Rosello, “Clausewitz’s Contempt for Intelligence,” Parameters 21 (Spring 1991), 103–114.

- Neil A. Lewis, “Spy Cases Raise Concern on China’s Intentions,” The New York Times, July 10, 2008.

- Paul D. Moore, “How China Plays the Ethnic Card,” Los Angeles Times, June 24, 1999.

- Narayan Lakshman, “U.S. jails China-based double agent,” The Hindu, March 6, 2013.

- See <http://mil.huanqiu.com/history/2012-09/3122927.html>.

- Office of the National Counterintelligence Executive, Foreign Spies Stealing U.S. Economic Secrets in Cyberspace: Report to Congress on Foreign Economic Collection and Industrial Espionage, 2009–2011 (Washington, DC: Office of the National Counterintelligence Executive, October 2011), i.

- U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, 2012 Report to Congress (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, November 2012), 7.

- OSD, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2013, 51–52.

- Richard D. Fisher, Jr., “China’s ‘New Relationship’ Trap,” Washington Times, August 26, 2013, B4.

- Zhang Yanbing, “Air Force Campaign Principles,” Chinese Air Force Encyclopedia (n.c.: Aviation Industry Press, 2005), 95–96.

- OSD, Annual Report to Congress: Military Power of the People’s Republic of China 2007 (Washington, DC: OSD, 2007), 12.