Download PDF

Jorge R. Kravetz is an independent academic researcher, professor, and senior technology consultant. He holds a master’s degree in national defense from the National Defence University (Argentina) and specializes in cybersecurity and Middle East affairs.

In December 2020, the United States experienced one of the most sophisticated cyber espionage attacks in its history: the SolarWinds supply chain breach. Information technology (IT) management software from the company SolarWinds was compromised by the introduction of malware through its network performance monitoring platform. The attackers, identified as being from the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service, accessed the infrastructure of numerous organizations, including U.S. Government agencies and private-sector companies, compromising sensitive data. The prolonged infiltration of critical systems revealed notable deficiencies in existing deterrence strategies.1

This incident parallels other historical espionage cases, such as Operation Ivy Bells during the Cold War, in which U.S. intelligence operatives covertly intercepted Soviet underwater communications cables for years without detection.2 These examples illustrate a recurring challenge: both cyber and traditional intelligence special operations frequently evade conventional deterrence measures. The question that motivates this research is how the deterrent effects of cyber operations and their potential failures relate to the deterrent effects of traditional intelligence special operations.

These activities exhibit similarities both in execution and impact. Like special operations, cyber activities often rely on espionage, sabotage, and subversion to destabilize adversaries without escalating to large-scale conflict. In this article, subversion denotes a deliberate attempt to undermine the authority, integrity, and constitution of an established order, without the need for violence or overthrow, such as through propaganda and disinformation campaigns.3 Retaliatory measures in both cases are generally tacit, based on implicit understandings of acceptable behaviors and exceptionally pre-agreed or normed, which complicate the establishment of clear boundaries. This raises the question of whether current deterrence frameworks can adequately address the evolving nature of these covert threats.

From a different perspective, this article examines a key issue in security studies: the possible causes of the failures of current deterrence strategies in cyberspace, focusing on their similarity to traditional intelligence special operations that were characteristic of the Cold War but continue to exist today. These operations may occur during periods of peace, tension, or competition, where they are employed to destabilize adversaries without escalating into armed conflict, or during times of war, where these tactics are adapted to support broader military campaigns. Despite countermeasures, both cyber and covert operations persistently evade state defenses, achieving tactical objectives that often challenge traditional understandings of deterrence. This study aims to contribute to the practice of cyber deterrence and security policy by demonstrating how these historical lessons can inform contemporary strategies.

Theoretical Foundations of Deterrence

According to Thomas Schelling, the aim of deterrence is to prevent or discourage an opponent from acting through fear or doubt. It involves diverting action through the fear of consequences.4 For Paul Huth and Bruce Russett, deterrence is a strategic interaction where a rational actor weighs costs and benefits based on expected adversary behavior. Deterrence is effective when a potential aggressor concludes that the costs of attack outweigh the benefits, making restraint the more advantageous option.5

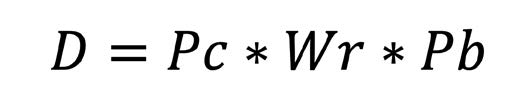

During the Cold War, Henry Kissinger argued that deterrence is a combination of power, the willingness to use it, and the aggressor’s perception of these factors. This relationship can be summarized as follows:

where D represents deterrence, Pc refers to power or the instrumental capability to retaliate, Wr is the will and resolve of the deterrer to act, and Pb is the aggressor’s perception and belief regarding the deterrer’s commitment to act. If any factor is zero, deterrence fails. Strength is ineffective without the will to apply it, and it fails if the aggressor doubts the credibility of the threat.6 Kissinger also suggests that retaliation should focus on not only destroying military capabilities but also affecting the adversary’s social substance.7

Additionally, Schelling describes how the effectiveness of threats depends on their credibility and severity. He emphasizes that responses must be severe enough to deter the adversary.8 He also introduces the role of “tacit agreements,” which are implicit understandings be- tween conflicting parties about acceptable behavior. These agreements establish unspoken boundaries that can prevent unnecessary escalation by clarifying expectations for conduct.9

The concept of tacit agreements underscores the importance of clarity and proportionality in responses, which are vital for maintaining stability. An excessively severe retaliation without a clear connection to the initial act of aggression may provoke further conflict. This reflects a central dilemma in deterrence theory: the challenge of balancing severity with credibility to ensure deterrence without triggering escalation.

The evolution of U.S. nuclear deterrence policy—from massive retaliation, where any act of aggression would be met with an overwhelming nuclear response, to Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD), where both parties face annihilation in a nuclear attack—illustrates strategic shifts in deterrence. The later introduction of tailored deterrence emphasizes the need to adjust responses based on the adversary’s specific capabilities and behavior, ensuring a proportional and credible response. This highlights the critical role of proportionality in avoiding unnecessary escalation.10

Deterrence theory has evolved to ad- dress the complexities of modern hybrid threats. It combines traditional military strategies with new forms of influence, such as cyber operations, information warfare, and economic coercion, emphasizing the importance of diplomatic efforts, economic sanctions, technological superiority, credible military threats, and strategic communication. This holistic approach aims to establish a robust deterrent posture, ensuring credible and effective responses to a diverse range of threats in an increasingly interconnected conflict environment.11

Special Operations and Deterrence

Special operations refer to state activities that differ from both diplomacy and conventional military actions, conducted as a “third option” between inaction and direct military engagement.12 For the United States, these covert actions aim to influence political, economic, or military conditions abroad while concealing government involvement.13 This work specifically considers special operations as those involving espionage, sabotage, and subversion—activities that have clear parallels in cyberspace—and is typically linked to strategic or military intelligence efforts and often executed by specialized agencies. Generally, these operations, whether conducted in peacetime or during conflict, fall into two main categories: those that require covert infrastructure for secure command and control by intelligence services, and short-term tactical operations planned by special forces and coordinated through military command structures and procedures.14

Despite the significant role of special operations in conflict dynamics, academic research exploring their deterrent impact remains limited. While it is not the purpose of this article to systematically investigate the reasons behind the lack of academic interest in this question—which undoubtedly deserves deeper analysis in the future—we can speculate that this lack of attention might be due to the classified nature of these missions, which restricts data access and minimizes the publicity of results; a possible tendency to focus on diplomacy and conventional military strategies; or the secrecy and possible lack of visible impact of covert operations, as is characteristic of military actions.

However, a recent study explores how special operations can serve as forms of “strategic disruption” that fall short of open warfare to deter escalation.15 These operations, conducted within indirect or low-intensity conflicts among major powers and their proxies, are reminiscent of Cold War dynamics and suggest a promising area for future research into the deterrent capabilities of special operations.

While this article focuses primarily on the military’s role in strategic disruption, it also highlights the potential of nonmilitary instruments within national power to contribute to these efforts. The study draws on extensive analysis of historical cases of special operations conducted by diverse nation-state military and intelligence organizations, suggesting insights applicable to activities involving espionage, sabotage, and subversion, which are planned and/or conducted by strategic or military intelligence agencies. These operations are significantly important in achieving favorable strategic outcomes without escalating to war.

Disruption campaigns aim to create strategic opportunities, impeding adversaries from achieving objectives and safeguarding national interests in diplomacy, information, military, and economic realms. This aligns with integrated deterrence, where military and nonmilitary instruments work together to sustain strategic advantage in competitive contexts. It explains that these disruptive campaigns do not need to produce strategic effects in and of themselves and highlights their unique potential to frustrate adversarial competitive objectives, particularly in situations where conventional deterrence alone proves insufficient to achieve similar outcomes. Consequently, strategic disruption campaigns, whether conducted by military or nonmilitary forces, seek to obstruct adversarial strategies and decisionmaking, imposing costs, creating dilemmas, and maintaining competitive advantage without resorting to armed conflict.

Similarly, special operations involving espionage, sabotage, or subversion conducted by strategic or military intelligence agencies could create favorable conditions for strategic influence, thereby supporting traditional deterrence efforts.

Understanding the repercussions of uncovered intelligence operations and the likely responses of targeted states is crucial for assessing their deterrent effect. Historical precedents suggest that espionage rarely leads to armed conflict. Such operations can lead to diplomatic protests, expulsions, eventual executions, persona non grata declarations, and the loss or turning of assets.16 Furthermore, these situations may result in trials, detentions, or imprisonment. Likewise, declassified cases indicate that sabotage and subversion rarely escalate into full conflict.

One example is the 1982 Farewell Dossier, where a U.S. strategic intelligence operation exploited Soviet efforts to acquire Western technology. The dossier, provided by a KGB defector codenamed “Farewell,” detailed Soviet intelligence’s extensive industrial espionage activities. In response, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) launched a counterintelligence operation, planting flawed technology—which would eventually trigger malfunctions—within equipment that the Soviet Union sought to acquire for its infrastructure. The incident caused a catastrophic explosion on a Siberian gas pipeline. This explosion led to significant economic setbacks for the Soviet Union without triggering a direct military confrontation. This case shows how strategic sabotage, when carefully calibrated, can inflict considerable harm without escalating into outright war.17

Similarly, the Soviet Union’s Cold War “active measures” campaign sought to manipulate public opinion, influence politics, and destabilize rival states through disinformation, clandestine media operations, and forged documents. Tactics included spreading false narratives about Western leaders, inciting social tensions, and planting doubt about U.S. intentions. These measures aimed to exploit societal divisions, undermining trust in democratic institutions and weakening alliances. While they fueled political turmoil in various countries, including in the United States, these operations remained largely below the threshold of direct military engagement, illustrating how calculated subversive efforts could exert significant influence without escalating into major conflict.18

These cases suggest that sabotage and subversion were integral to broader strategic competition, illustrating their effectiveness in undermining adversaries without resorting to overt war. The limited repercussions observed may stem from tacit agreements on acceptable boundaries and reprisals, which influence state decisions regarding covert operations. As discussed, when states anticipate minimal consequences, they are less deterred from conducting such operations and may use them to complement their overall deterrence strategy. Conversely, when targeted states understand that responses will be limited by these tacit agreements, their ability to deter further operations may be restricted.

Cyber Operations and Deterrence Framework

While special operations and deterrence remain less explored, cyber deterrence has garnered substantial attention, likely due to early-21st-century fears of a “Cyber Pearl Harbor.”19 This perceived threat involved catastrophic impacts on critical infrastructures, such as power grids, financial systems, and even military or social networks. Consequently, the concept of cyberwar as a unique form of warfare within cyberspace gained prominence, fueling further academic interest in cyber deterrence strategies.20

This analysis defines cyber operations as including cyberattacks, disinformation, and propaganda campaigns in cyber-space. A cyberattack deliberately targets a computer system’s integrity, availability, or confidentiality through malicious software, deceptive tactics, or vulnerabilities in software, hardware, or network configurations. The aim is to gain access, damage or steal information, and/or degrade, disrupt, or block the functioning of such systems. This definition excludes electromagnetic warfare techniques, which exploit the electromagnetic spectrum, and hybrid warfare activities, which could combine cyber operations with kinetic force.21

Martin Libicki highlights unique challenges in cyber deterrence, particularly in attributing cyberattacks, a task that becomes more complex when proxies are involved. He suggests a combination of retaliation threats, active defense, and regulation to deter the usage of cyber weapons. The distinction is made between strategic cyberwarfare—operating solely in cyberspace, avoiding violence, and remaining sub rosa—and operational cyberwarfare, where cyberattacks support military actions. Questions such as “Do we know who did it?” “Can we hold their assets at risk?” and “Can we do it repeatedly?” illustrate the complexities of cyber deterrence. Libicki also highlights that, unlike conventional shows of force, real cyberattacks are often needed to demonstrate deterrent capacity, introducing added uncertainty.22

More recently, Libicki highlights the uncertain effects of cyberattacks resulting from their unpredictable outcomes in comparison to traditional weapons. He states that cyberattacks aimed at espionage, sabotage, and subversion can harm adversaries but argues that cyber deterrence is most effective when integrated with other methods, such as kinetic deterrence. He notes that reliance solely on cyber operations for deterrence is limited because of their unpredictable impact.23

Joseph Nye sees cyber deterrence as uniquely challenging compared to conventional and nuclear deterrence and emphasizes the difficulties of attribution. In addition to punishment and denial through defense to deter aggression, two political factors play a crucial role: entanglement, where economic interdependence raises potential costs for attackers, and normative taboos, which involve ethical and reputational considerations that deter aggression. Consequently, effective deterrence here depends on various factors, including the method of implementation (threats of punishment, defense, entanglement, or norms), the nature of the adversary (state or nonstate), and the type of action being deterred (for example, use of force or economic sanctions). While this multidimensional approach aligns with the broader concept of hybrid deterrence mentioned earlier, Nye’s framework remains circumscribed to cyberspace, describing how hybrid deterrence strategies can also be applied specifically within this domain.24

Nye also argues that cyber weapons have thus far proved more effective for signaling or creating confusion than for causing physical destruction. He suggests that we may be looking in the wrong direction, as the real danger lies in the gray zone of hostility—conflict below the threshold of conventional war—where rapid and inexpensive digital disinformation can confuse and divide adversaries, making cyberattacks the perfect weapon for warfare below the level of armed conflict.25

Additionally, the concept of strategic disruption in cyberspace should be highlighted. These capabilities are not only used to gather intelligence and influence adversary movements but also enable strategic disruption by creating opportunities for special operations forces in hostile environments. As technology rapidly advances, these cyber capabilities are expected to increasingly impact special operations forces’ ability to conduct disruption campaigns.26

The initial focus on cyber deterrence was shaped by perceptions of the severe consequences of cyberattacks, drawing parallels with classical deterrence theories and emphasizing attribution issues. However, this view is shifting; the anticipated severity has not materialized, and cyber operations are increasingly regarded as effective support for kinetic operations. Moreover, cyber operations are seen as tools for espionage, sabotage, and subversion within the gray zone of hostilities. This aligns with the concept of strategic disruption, as these activities create opportunities by hindering adversaries from achieving their objectives while remaining below the threshold of conventional warfare.

Continuities Between Special and Cyber Operations

Thomas Rid notes that cyberwar—as a potentially lethal, instrumental, and political act of force conducted through malicious code—has not happened in the past, does not take place in the present, and is unlikely to occur in the future. He argues that politically motivated cyberattacks can be considered as manifestations of espionage, sabotage, and subversion, reflecting old conflict tactics adapted to a digital domain. He concludes that despite their technical sophistication, cyberattacks pursue the same strategic objectives as traditional intelligence operations. Additionally, he suggests that while these activities can certainly support military operations and have been used for that purpose for centuries, it remains uncertain whether they will evolve into stand-alone acts of cyberwar.27

Building on Rid’s framework, an additional study compares state-sponsored special operations with modern cyber counterparts from the 20th and 21st centuries. This study reveals parallels in motivations, objectives, results, impacts on foreign relations, and the role of strategic or military intelligence agencies in planning and execution. Moreover, it situates these cyber operations within the realm of cyber intelligence, positioning them as strategic intelligence activities conducted “in and from” cyberspace toward other domains, illustrating the evolution of traditional covert intelligence activities into the cyber realm.28

Examples and Impacts. Notably, 20th-century state-sponsored intelligence operations in espionage, sabotage, and subversion often lacked immediate visible strategic impacts on individuals, assets, institutions, or social cohesion within targeted states. While they could yield favorable tactical results, these actions rarely resulted in significant lasting shifts in social or power structures as well as in the adversary’s global policies.

For instance, in 1957, Soviet spy Rudolf Abel was arrested in the United States while engaged in stealing atomic secrets and gathering top-secret intelligence from the United Nations and U.S. military installations. He was convicted of conspiracy and espionage and sentenced to 45 years in prison. Later, he was exchanged for an American pilot in a spy swap between the United States and the Soviet Union. Despite the diplomatic repercussions of this incident, Cold War activities between the two nations continued largely unchanged.

In 1960, Francis Gary Powers, a pilot of a U-2 spy plane operated by the CIA, was shot down while conducting reconnaissance over Soviet territory. This incident occurred as both nations intensified their espionage efforts. After his capture, the Soviet government portrayed Powers as a spy, leading to international controversy and a diplomatic crisis. He was tried in Moscow and sentenced to 10 years, although he served only 4 before being exchanged for Abel in 1962. Both cases sparked diplomatic tensions but ultimately did not escalate into wider conflicts, illustrating the typical or tacit consequences of revealed intelligence activities.29

The Farewell Dossier exemplifies a significant act of sabotage by the United States that did not lead to immediate shifts in the Soviet Union’s power dynamics or global policies. Although it disrupted Soviet gas pipelines, affected technological logistics, and caused economic losses, its impact was not substantial enough to undermine internal social cohesion, shift political power, or alter the country’s foreign policy. Nor did it escalate into a full-scale armed conflict or change the overall dynamics of the Cold War.

In the late 1970s, the Soviet Union conducted an “active measures” campaign aimed at distancing Egypt from its alliance with the United States, undermining the 1978 Camp David Accords, and escalating tensions in the Middle East. Through disinformation, propaganda, and document forgery, Soviet efforts spread rumors to discredit both Egyptian and American presidents. While these actions introduced tensions and internal pressures in Egypt, they ultimately failed to break the U.S.- Egypt alliance or undermine the Camp David agreement. As a result of these subversion campaigns, the report by the Bureau of Public Affairs of the U.S. Department of State noted that the general responses of countries that discovered Soviet active measures included well-publicized expulsions of diplomats, journalists, and others involved in these activities, with no escalations, and the Cold War continued as usual. 30

During 2024, in the cyber realm, seven Chinese intelligence officers linked to China’s Ministry of State Security were indicted for hacking into the systems of U.S. companies, politicians, governmental institutions, and officials since 2010, including those in the defense industry, critical infrastructure sectors, and individual dissidents worldwide. While this led to legal actions by the U.S. Department of Justice and sanctions imposed by the Department of the Treasury against the individuals and companies involved, it did not prompt any escalation, reflecting the application of tacit agreements concerning discovered intelligence operations.31

In 2015, Ukraine’s power grid suffered an attack attributed to Russian nation-state cyber actors, marking the first cyberattack to cause a large-scale blackout. This sabotage was carried out by a hacking group that used destructive malware to compromise the industrial control systems of electrical substations. The attack significantly impacted the country’s critical infrastructure, leaving 225,000 users without electricity for several hours. However, the system managed to recover, and aside from the protests, no significant escalations occurred, with the conflict between Russia and Ukraine remaining unchanged because of this incident.32

During the 2017 French presidential election, a foreign entity linked to Russian military intelligence interfered in the voting process through a disinformation campaign against candidate Emmanuel Macron. This subversion campaign included spreading rumors on social media platforms as well as leaking of data hacked from Macron’s campaign team. Although these efforts aimed to sway public opinion among the electorate, they did not apparently produce significant changes in the electoral landscape.33 However, following his election, Macron made public protests against Russian state–backed media outlets RT and Sputnik, accusing them of acting as “organs of influence and propaganda” during the campaign.34 This reflected a deterioration in trust between the two countries, although it did not lead to a major diplomatic friction, nor did it escalate into a larger conflict between France and Russia.

All these cases illustrate that special operations—whether related to espionage, sabotage, or subversion, and whether conducted in traditional or cyber domains—may yield tactical or even limited strategic outcomes for the attacker. However, they often fail to achieve significant strategic impacts on the target or provoke severe or extreme retaliation. Furthermore, these retaliations tend to operate within the bounds of tacit agreements, which frequently shape the nature of the responses.

Strategic Impact. Here, strategic impact encompasses kinetic or nonkinetic effects so significant in terms of the costs imposed on the adversary—whether immediate or gradually consolidating—that they hinder a short-term return to the previous strategic situation across four main areas:

- Social cohesion: Disruptions in social stability, including displacements, humanitarian crises, unrest, or casualties, weakening government legitimacy.

- Economic impact: Disruption to critical infrastructure, destabilization of financial institutions, losses in strategic sectors of the economy, erosion of internal and external economic confidence, and loss of other sources of income, causing economic stability.

- Political structure: Significant changes within government or state institutions, including shifts in political power, leadership changes, or alterations in governance frame- works. These changes may alter domestic or foreign policy as well as the legitimacy of governing bodies, affecting defense posture and national security strategy.

- Military structure: Reductions in military capability, readiness, or effectiveness, affecting defense posture and national security strategy.

For robust deterrence, threats of retaliation should ensure not only tactical success but also substantial lasting costs and consequences for the adversary.

Deterrence Representation Model. Kissinger’s deterrence model, as previously discussed, assumed clear attribution guaranteed by kinetic aggression, with responses based on mutual retaliation, especially under the concept of MAD. During the Cold War, both the immediacy of attribution and the strategic impact of a nuclear strike were so self-evident that they required no formalization and thus were not explicitly included in the deterrence models of that era.

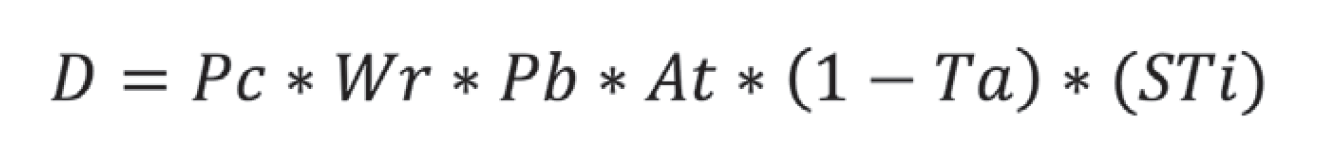

Building on this classical conception, we propose an adapted deterrence representation model designed to assess potential vulnerabilities in deterrent posture and evaluate its overall effectiveness. This model is conceptual and illustrative. It is meant to reflect the complexities of modern deterrence, particularly in the special operations and cyber domains, by integrating factors such as “attribution,” “tacit agreements,” and “strategic impact,” rather than to generate precise numerical predictions.

These elements can lead to failures or weakened deterrent postures while also assisting in evaluating varying degrees of efficacy. By including cyber considerations, our modern deterrence model encompasses a broader range of factors:

where D represents deterrence; Pc is the power and capability of the deterrer to retaliate; Wr represents the will and resolve of the deterrer to act; Pb is the aggressor’s perception of the deterrer’s resolve to act; At represents the capacity of the deterrer to attribute, both intellectual and material, the attack (At = 1 indicates capacity; At = 0 indicates failure of deterrence); Ta represents tacit (or explicit, if they exist) agreements (Ta = 1 indicates agreements in place, Ta = 0 indicates no agreements— these represent the unspoken or formalized understandings that the deterrer is expected to uphold when responding to an attack); and STi reflects the deterrer’s evaluation of the likely kinetic or non- kinetic effects their retaliation would have on the adversary’s political, social, economic, and military situations. Note: Values exceeding 1 are not permitted. D = 0 implies uncertainty or potential failure, not necessarily absolute nullification of deterrence.

Two approaches are proposed: Binary Representation. Here, Pc, Wr, Pb, At, and STi are limited to values of 0 or 1. If any factor equals 0, then D = 0, indicating a potential failure of deterrence.

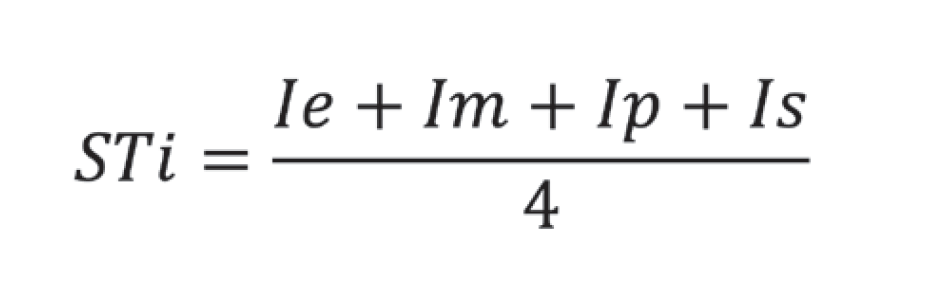

Estimative Representation. In this case, Pc, Wr, and Pb can take values from 0 to 1, inclusive. If any factor equals 0, deterrence could fail; values between 0 and 1 indicate the parameter’s existing level, with STi calculated as follows:

Standard representation:

where each I represents an impact—economic, military, political, or social. A value of 1 indicates presence, while 0 indicates absence. The sum is divided by 4 to ensure STi remains between 0 and 1. If STi = 0, deterrence fails; any value greater than 0 suggests a partial deter- rent effect, indicating some strategic impact contributes to deterrence.

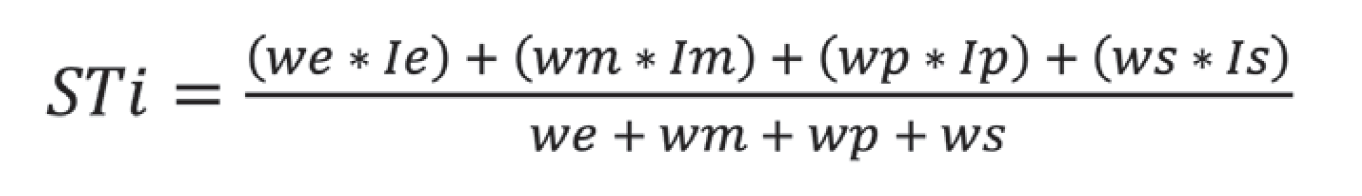

Weighted Average: For a more quantitative threshold, weights can be assigned to each impact type to reflect its relevance:

where Ie, Im, Ip, and Is remain the impact factors, and we, wm, wp, and ws are their respective weights. As in the estimative case, here even if one impact factor is zero, others may sufficiently sustain deterrence. If all weights are equal to 0, this indicates irrelevance in the considered impact areas, necessitating the use of the standard representation of STi. In all estimative calculations, multiplying the formula by 100 will yield a percentage estimation of deterrence.

Important Considerations

This framework is a starting point. New factors and more nuanced adjustments can be added to the model as needed to capture specific scenarios. The binary representation model focuses on evaluating the potential failure or success of deterrence by assigning direct values, while the estimative models offer more flexibility by allowing subjec- tive estimations of certain parameters and accounting for different strategic impacts. The weighted STi approach allows certain impacts to have more influence on the overall assessment.

However, the subjective nature of these estimations and the challenge of quantifying impacts should be considered, along with the need to ensure transparency regarding methodology and consistency throughout this process. Additionally, the model’s reliance on rational actor behavior may not always hold, as emotions, ideologies, and misperceptions can significantly influence decisionmaking. Its use should be approached with caution, especially in complex scenarios where additional variables may emerge.

For instance, the question “Can we do it repeatedly?” could introduce an additional term: D = Do * Rp, where Do denotes the original formula and Rp represents repeatability. If Rp = 0, then D = 0, indicating possible deterrence failure. Similarly, entanglement (E), reflecting external constraints like those imposed by the international community, can be added, giving D = Do * Rp * (1 – E). If E = 1 (entanglement in place), then D = 0, indicating a weakened deterrence posture.

Conclusions

Since the emergence and intensification of state-sponsored operations in cyberspace throughout the 21st century, academic interest in the deterrent effects of this new domain of conflict has markedly increased. Initially, this interest was predicated on the assumption that cyber operations, or cyber warfare, could inflict catastrophic damage on adversaries. It was anticipated that these operations would exert an effective deterrent influence comparable to that of conventional or nuclear weapons in the past. However, it has become increasingly evident that cyber operations among states have escalated without achieving effective deterrence against such attacks.

This evolving scenario has spurred scholarly inquiry into the underlying dilemmas of deterrence failures in cyberspace, particularly as these challenges diverge from classical deterrence theories. Notably, this area has not been thoroughly examined within academia in relation to traditional special operations. This lack of attention may result from the secrecy surrounding their impacts or from the prevailing belief that such operations do not significantly alter the existing social or power dynamics of the adversary.

Drawing on a rigorous theoretical framework, academic studies, and historical examples, we have identified a clear pattern in state-sponsored intelligence special operations—encompassing both traditional and cyber domains—and demonstrating continuity in the strategies of espionage, sabotage, and subversion. While these operations may yield tactical successes, their long-term strategic impact on foreign relations, as well as on the social, economic, and power dynamics of states, appears more limited.

Moreover, emerging investigative perspectives view both special and cyber operations as continuous and integral components of strategic disruption, serving as vital complements to the overall deterrent posture of states. In this context, the significance of agreements—whether tacit or explicit—should not be underestimated. These agreements play a crucial role in moderating state responses and preventing the escalation of armed conflicts or war.

The adaptation of the classical deterrence model from the Cold War incorporates elements such as the viability of attribution, the existence of tacit agreements, and strategic impacts. As a preliminary illustrative framework, this adaptation allows us to highlight the complexity of evaluating, a priori, the potential degree of effectiveness or failure of contemporary deterrence, including cyber. This proposed dynamic and adjustable model reflects the hybrid and constantly evolving nature of modern conflicts.

The dilemma of cyber deterrence, much like that of traditional special operations, highlights the limitations of these approaches as stand-alone deterrent strategies. Instead, both serve as integral components that reinforce the broader deterrent posture of states, consistent with the principles of hybrid deterrence. Understanding the dynamics of deterrence within traditional special operations is therefore essential to comprehending the current limitations of cyber deterrence. Notably, the apparent failure of cyber deterrence is not entirely unprecedented; it reflects a historical continuity with the persistent challenges of deterring covert operations such as espionage, sabotage, and subversion. In simpler terms, both cyber and covert special operations—although often invisible or plausibly denied—are central tools through which states compete while avoiding full-scale war. Recognizing this continuity helps governments understand today’s strategic environment more clearly and design more realistic and adaptive national security strategies. JFQ

Notes

1 2021, https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/cybersecurity-advisories/aa20-352a.

2 Associated Press, “Experts Say Soviets Learned ‘Nothing New’ From NBC Show,” Washington Times, May 21, 1986, declassified by the Central Intelligence Agency, May 8, 2012, CIA-RDP90-00965R000605470011-1, https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP90-00965R000605470011-1.pdf.

3 Thomas Rid, “Cyber War Will Not Take Place,” Journal of Strategic Studies 35, no. 1 (2011), 22, https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2011.608939.

4 Thomas C. Schelling, Arms and Influence (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2020), xviii.

5 Paul Huth and Bruce Russett, “What Makes Deterrence Work? Cases From 1900 to 1980,” World Politics 36, no. 4 (1984), 499–500, https://doi.org/10.2307/2010184.

6 Henry A. Kissinger, The Necessity for Choice: Prospects of American Foreign Policy (London: Chatto & Windus, 1960), 12; R. Goychayev et al., Cyber Deterrence and Stability: Assessing Cyber Weapon Analogues Through Existing WMD Deterrence and Arms Control Regimes, PNNL-26932 (Richland, WA: Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, September 2017), https://www.pnnl.gov/main/publications/external/technical_reports/PNNL-26932.pdf.

7 Kissinger, The Necessity for Choice, 64.

8 Schelling, Arms and Influence, 3.

9 Thomas C. Schelling, The Strategy of Conflict (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1960), 53–80.

10 Rosemary Avance et al., United States Deterrence Policy: 1944–Present (Stillwater, OK: Media Ecology and Strategic Analysis Group, September 2023), https://mesagroup.okstate.edu/images/FINAL_LITERATURE_REVIEW.pdf.

11 Avance et al., United States Deterrence Policy, 28–9.

12 Mark M. Lowenthal, The Future of Intelligence (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2018), 100.

13 U.S. National Intelligence: An Overview 2013 (Washington, DC: Office of the Director of National Intelligence, 2013), 72, https://web.archive.org/web/20241208034229/https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/USNI%202013%20 Overview_web.pdf.

14 Gonzalo Bravo Tejos, “Operaciones especiales: una visión amplia y actualizada del concepto” [Special operations: a broad and updated view of the concept], Revista de la marina 134, no. 958 (2017), https://revistamarina.cl/es/articulo/operaciones-especiales-una-vision-amplia-y-actualizada-del-concepto.

15 Eric Robinson et al., Strategic Disruption by Special Operations Forces: A Concept for Proactive Campaigning Short of Traditional War, RR-A1794-1 (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, December 5, 2023), https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1794-1.html.

16 Michael Warner, “Intelligence in Cyber— and Cyber in Intelligence,” in Understanding Cyber Conflict: 14 Analogies, ed. George Perkovich and Ariel E. Levite (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2017), 17–29, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2017/10/understanding-cyber-conflict-14-analogies.

17 Peter C. Oleson, “When Intelligence Made a Difference: Cold War—Farewell Dossier,” Intelligencer: Journal of U.S. Intelligence Studies 29, no. 1 (2024), 75–84, https://www.afio.com/assets/publications/excerpts/OLESON_ Farewell_Dossier_AFIO_Intelligencer_Vol29_ No1_WinterSpring_2024.pdf.

18 “Soviet ‘Active Measures’: Forgery, Disinformation, Political Operations,” Special Report No. 88, U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Public Affairs, October 1981, CIA-RDP 84B00274R000100040004-8, released March 12, 2007, https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA- RDP84B00274R000100040004-8.pdf.

19 See Sharon Weinberger, “Cyber Pearl Harbor: Why Hasn’t a Mega Attack Happened?,” BBC, August 19, 2013, https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20130820-cyber-pearl-harbor-a-real-fear.

20 See Martin C. Libicki, Cyberdeterrence and Cyberwar (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2009), 8–9, https://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG877.html.

21 See Arsalan Bilal, “Hybrid Warfare— New Threats, Complexity, and ‘Trust’ as the Antidote,” NATO Review, November 30, 2021, https://web.archive.org/web/20250326015959/https://www.nato.int/docu/review/articles/2021/11/30/ hybrid-warfare-new-threats-complexity-and-trust-as-the-antidote/index.html; North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “Electromagnetic Warfare,” last updated March 22, 2023, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/ topics_80906.htm.

22 Libicki, Cyberdeterrence and Cyberwar.

23 Martin C. Libicki, “Expectations of Cyber Deterrence,” Strategic Studies Quarterly 12, no. 4 (2018), 44–57, https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/SSQ/documents/Volume-12_Issue-4/Libicki.pdf.

24 Joseph S. Nye, Jr., “Deterrence and Dissuasion in Cyberspace,” International Security 41, no. 3 (2016–17), 44–71, https://doi.org/10.1162/ISEC_a_00266.

25 Joseph S. Nye, Jr., “Is Cyber the Perfect Weapon?,” Project Syndicate, July 5, 2018, https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/deterring-cyber-attacks-and-information-warfare-by-joseph-s--nye-2018-07.

26 Robinson et al., Strategic Disruption by Special Operations Forces, 59.

27 Rid, “Cyber War Will Not Take Place,” 5–32.

28 Jorge R. Kravetz, “Operaciones especiales en el ciberespacio: espionaje, sabotaje y subversión en el siglo XXI” [Special operations in cyberspace: espionage, sabotage, and subversion in the 21st century],” Revista de la Escuela Nacional de Inteligencia 3 (July–December 2023), 35–64, https://doi.org/10.58752/1PVI0VZ2.

29 “Rudolf Abel and the Hollow Nickel Case,” Federal Bureau of Investigation History, n.d., https://www.fbi.gov/history/artifacts/rudolph-abel-hollow-nickel-case; “U-2 Overflights and the Capture of Francis Gary Powers, 1960,” Department of State, Office of the Historian, n.d., https://history.state.gov/milestones/1953-1960/u2-incident.

30 “Soviet ‘Active Measures.’”

31 “Seven Hackers Associated With Chinese Government Charged With Computer Intrusions Targeting Perceived Critics of China and U.S. Businesses and Politicians,” Department of Justice, March 25, 2024, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/seven-hackers-associated-chinese-government- charged-computer-intrusions-targeting-perceived.

32 “Cyber-Attack Against Ukrainian Critical Infrastructure,” CISA, July 20, 2021, https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/ics- alerts/ir-alert-h-16-056-01.

33 Jean-Baptiste Jeangène Vilmer et al., Information Manipulation: A Challenge for Our Democracies (Paris: Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs and Ministry for the Armed Forces, August 2018), 106–16, https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/information_ manipulation_rvb_cle838736.pdf.

34 Erik Brattberg and Tim Maurer, Russian Election Interference: Europe’s Counter to Fake News and Cyber Attacks (Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2018), 11, http://www.jstor.com/stable/resrep21009.6.