DOWNLOAD PDF

Major Mike Rybacki, USA, is an Academic Instructor in the Department of Behavioral Sciences and Leadership at the United States Military Academy. Major Chaveso “Chevy” Cook, USA, is Commander of Delta Company, 3rd Military Information Support Battalion (A), Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

Ask any member of the U.S. Armed Forces if they have witnessed firsthand the effects of a toxic leadership environment, and they will almost certainly say “yes.” They will usually further elaborate on the damning effects of the toxic environment by providing examples of everything from combat ineffectiveness to low rates of retention and morale.1 Given this depth of information, we must ask, “Why is there not a proactive approach to preventing these leaders from advancing in leadership roles?” The purpose of this article is to provide an overview of the current thoughts on toxic leadership and provide an actionable approach for countering and preventing the development of toxic leader environments.

Air Force Reserve security forces members participate in 6-day combat leaders course while living in field conditions, placing practical application of combat maneuvers into complex mission environments (U.S. Air Force/Nicholas B. Ontiveros)

Toxic Leadership Defined

The definition we will use is presented by Art Padilla, Robert Hogan, and Robert B. Kaiser in their article titled “The Toxic Triangle: Destructive Leaders, Susceptible Followers, and Conducive Environments.”2 The authors evaluate conflicting and competing language in the work of previous authors, psychologists, and social scientists. They first refute the idea that leadership by definition is only a “positive force,” where “positive” would mean using human energy and resources to influence others to create a desired result. Subscribers to this line of thinking would argue that toxic leaders are not leaders at all. Narrowing the definition of leaders to those individuals who have only a positive influence becomes problematic when evaluating their “influence” over time and across the many individuals/groups one leader could affect. Similarly, toxicity in an organization exists regardless of the broad ranges of leader competence and effectiveness. In broader terms, the leader in question may or may not be entirely successful in leading his or her organization.

Furthermore, these authors argue that definitions of toxic leadership as a process or as an outcome exclusively are incomplete. Viewing destructive leadership as the result of a leader’s behavior within a process “assumes that a leader’s bad intentions are an essential component of destructiveness” and that “certain behaviors are inherently destructive.”3 Some undesirable behaviors, such as egocentrism, will not always lead to a toxic situation. Viewing toxicity as entirely an outcome is limiting in that even “good” leaders may produce “bad” outcomes.4

After determining what toxic leadership is not, the central argument presented by Padilla, Hogan, and Kaiser is that previous definitions of toxic leadership that focus solely on the leader are too narrow and incomplete. Denise Williams identified 18 different attributes and “types” of leaders in her research.5 Prefaced by the reminder that even a destructive leader must be truly “leading” by influencing others to forego their interests and contribute to long-term goals, Padilla, Hogan, and Kaiser identify the attributes of a toxic leader as five “elements”: charisma, personalized power, narcissism, negative life theme, and ideology of hate.6 These attributes are not sufficient, however, due to the contextual influence and role of followers in an organization.7

Followers in a toxic situation are defined as being either “conformers” or “colluders.” Conformers have unmet needs, low maturity, and/or low core self-evaluation. This explains why populations living in poverty can be susceptible to tyrannical leaders. Colluders, on the other hand, seek to benefit from a toxic situation alongside the leader. This group is defined as having ambition, a similar world view as the leader, and “bad” values. The environment must also be “conducive” for a toxic leader and susceptible followers to persist. Instability, perceived threat, cultural values, a lack of checks and balances, and ineffective institutions are the elements of an environment in which a toxic situation may arise.

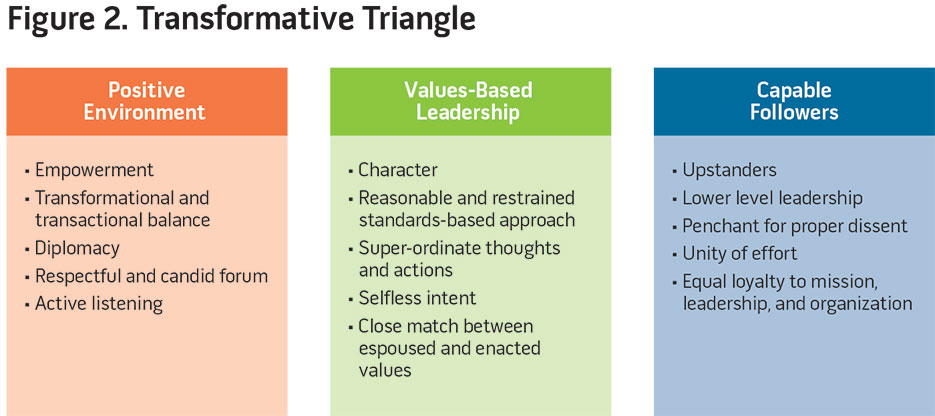

The Transformative Triangle

In an effort to simplify a complicated issue, we propose our triangle of elements in figures 1 and 2. Each major component has subcomponents, which will be further discussed. Also shown in figure 1 is a juxtaposition of our transformative triangle versus Padilla, Hogan, and Kaiser’s toxic triangle. Both environments are “infectious.” Both seep deep into the culture and the individual members of the organization. For purposes of this discussion, we propose that in a toxic context, the destructive leader is the primary driver of toxicity, while in a constructive context, the positive environment is the primary driver of transformative outcomes. This is visually represented at the apex of each triangle.

Positive Environment

A positive atmosphere is one that is uplifting, supportive, and developmental in nature. Research has shown that when people “work with a positive mind-set, performance on nearly every level—productivity, creativity, engagement—improves.”8 We also know that effective leadership is context dependent.9 Understandably, it may be especially difficult to measure positivity. Here we use five measures as indicators of a positive environment: empowerment, transformational and transactional balance, active listening, diplomacy, and a respectful and candid setting.

Empowerment. To empower is to invest, equip, enable, or supply someone with power. All of this requires a certain amount of giving. Leaders have to pour themselves into others and their efforts. A leader must create action, devote time, make space, provide opportunity, mentor, coach, teach, and work on behalf of others to empower them. Constructive leaders are those who understand that they are obligated to endow followers with the ability to do what is needed. John Steele, author of a study released by the Center for Army Leadership in 2011, proposes that constructive leadership is the result of a leader whose focus is pro–organizational behaviors, pro–self-interests, and pro–subordinate behaviors.10 The one differentiation made between this and a toxic environment is the empowerment of subordinates—whether leaders look to accomplish organization objectives through subordinates or in spite of subordinates.

Transformational and Transactional Balance. Environments that focus on development work toward growing leaders rather than creating better followers. Transformational practices look to restructure and renew members of the organization. Transformational leadership “fosters capacity development and brings higher levels of personal commitment among followers to organizational objectives.”11 Steele finds that “units that make leader development a higher priority also tend to report fewer toxic leaders, and consider toxic leadership less of a problem.”12 Transactional practices are not on the other end of the spectrum, per se, as they are more akin to a different practice altogether. Transactional leadership focuses more on “exchanging tangible rewards for the work and loyalty of followers.”13 Transactional processes are needed to get the job done, and a can-do attitude facilitates results. It has been suggested that subordinates, however, generally want more developmental experiences. When this is not the case, many junior leaders and subordinates feel like they are less capable.14 Therefore, a balance must be sought to get tasks accomplished and facilitate growth.

Active Listening. Active listening is a combination of synthesizing another’s information in conversation while not simultaneously formulating our own subsequent retort. It requires that we not multitask while engaging in discussion, denouncing the widely held belief that pausing for silence after one is finished speaking is a sign of misunderstanding, weakness, or unpreparedness in an engagement. Leaders truly understand the importance of active listening if they can pay attention and actively pinpoint another’s perspective. Other tenets of active listening are:

- ask appropriate questions

- stop and pay attention

- use physical listening (that is, body language, eye contact)

- withhold judgment

- pick up on emotions/feelings

- pause to reflect

- synthesize the information

- restate, paraphrase, or summarize.

Carl Rogers’s person-centered approach to humanistic psychology and psychotherapy suggests that “humans will allow themselves to be influenced only after they decide they have been heard and understood.”15

Diplomacy. Author Paul Arden describes the importance of diplomacy, telling us that we must take into account what others desire, as it will soften our approach and prepare them to look at what we want to show them.16 He then goes on to specifically state that doing so allows them to be magnanimous rather than shoving them in a corner.17 It is giving a little to get a little, but more often than not, it is giving a little to get so much more. Our decisions as leaders greatly affect our followership’s environment. They affect our leaders, too. Bringing them all into our decisionmaking process garners ownership of what results we may achieve together. Diplomacy breeds connectedness, which in many cases takes us from sympathy to empathy. Accurate empathetic understanding is paramount to deciphering the human experience, which gives leaders a better perspective. Being empathetic is not just some sort of banal platitude, as the emotional quotient has become as important to leadership and decisionmaking as the intelligence quotient. Taking this up a level from the individual to the group, through research on organizations, Rensis Likert found that the ideal executive approach from the perspective of the led clusters around participative management as opposed to autocratic management, benevolent autocracy, or even consultative management.18 Yan Ye confirms the findings of Likert, stating that “autocratic leadership is likely to produce passive followers.”19

Respectful and Candid Setting. Respect goes in all directions in an organization that has a positive environment. It is not only afforded to those in positions of authority. All members of the organization owe each other respect. True respect should extend to all exchanges, be it around the water cooler, in a presentation, during a working group, or elsewhere. Followers owe leaders the ground truth, and Steele’s study indicates that constructive leaders often take advantage of this by encouraging “frank and free-flowing idea discussion.”20 These leaders seek to foster an atmosphere that is conducive to connections, especially in this era filled with hyper-connectivity. Ye states that the advent of the information age has “highlighted the need for more flexible leader-follower relationships.”21 Our ability to quickly reach out to each other has allowed us to know more than just what followers think. Likewise, Kent Bjugstad finds that effective leaders also need to create the environment that garners respect for followers “who will speak up and share their points of view rather than withhold information.”22 This all suggests that mutual respect sets the foundation for quality relationships.

Values-Based Leadership

Noted leadership consultant John Maxwell writes in The 360° Leader that “decisions that are not consistent with our values are short lived.”23 With recent studies from the Army’s Command and General Staff College finding lying commonplace in the U.S. Army’s officer corps and numerous stories demonstrating moral failures in everything from politics to the business industry, value judgment has taken center stage. In a constructive environment, values can “influence both one’s effectiveness and the climate in which [he] work[s].”24 Values provide leaders, and followers to a certain extent, an anchor in unsettling situations. In today’s unstable security environment, leaders are being put into dangerous situations more often. The three components of psychological readiness for leadership in difficult contexts are caring, competence, and values.25 Teams will be more apt to have mutual trust and cohesion when the leaders derive their actions and decisions from values.

Character. Character is paired with commitment and competence in the profession of arms as defined in Army Doctrine Publication 6-22, Army Leadership.26 Maxwell argues that our behavior determines the culture, our values determine decisions, our attitude determines the atmosphere, and our character determines the trust in an organization.27 Leaders who display upright character through both behavior and values will have a culture of trust in their organizations. Steele states that there is a strong relationship between constructive leadership and behaving ethically, wherein there lie inviolable moral principles.28 Lacking principles may lead to a bending of rules that destroys the trust that connects a leader and followers. Steele further states that there is a strong relationship between constructive leadership and behaving ethically.29 Mutual trust allows working toward goals on behalf of the whole, where followers trust that the leader is taking them in the right direction and that the leader trusts that the followers will do the right thing(s) to accomplish that goal. James O’Toole argues that without committed understanding couched within morals and values, trust will be broken and the leader will not be followed.30

Reasonable and Restrained Standards-Based Approach. The military is a standards-based organization. Steele reminds us that even micromanagement can be effective “when a subordinate is incompetent or wants tight guidance.”31 Different types of followers may require different leadership approaches to get the most out of them. Path-goal theory tells us that leader behavior is dictated by both the composition of their followership and the characteristics of the task at hand, spanning from a directive style to an achievement-oriented style.32 As mentioned earlier, leadership approaches can be democratic to a certain extent, as the interactions between leaders and followers can and will at times determine our outcomes. Before leader-member exchange theory, for example, most research focused solely on the approach that leadership was something leaders did to followers, as opposed to with followers.33 We should hold followers accountable, but not to the point of neglecting simple courtesy. For example, if gloves are required for work or training, then that is the standard to be adhered to. But if it is raining so badly that gloves are soaked to the point of deteriorating the wearers’ hands, a leader should no longer require followers to wear gloves, to let their gloves and hands dry out.

Superordinate Thoughts and Actions. Many of our military standards derive from tradition. Traditions only stay alive because of leaders and followers. Institutions are built upon traditions, as well as standards, norms, ethics, credentials, and even schedules. But they do not honor themselves; members of the organization honor them. Institutions need people to make them what they are. Members of the organization tell others, by words and deeds, what institutions stand for. When leaders focus on upholding the institution, they focus less on the story they become. The institution is bigger. One should not read “bigger” strictly through the lens of size, though it is an important and unforgettable dimension with respect to this definition. It should be thought of from the broader sense of importance. This importance is heavily derivative from esteemed tradition(s) developed over time, long before the current member was part of the organization. A values-based leader carries on the institution because it is guaranteed to outlive all existing members of the organization.

Selfless Intent. Dysfunctional leadership behaviors, including self-centered attitudes and motivations, adversely affect subordinates, the organization, and mission performance.34 In a Military Review article, Joseph Doty and Jeff Fenlason find that almost all toxic leaders are narcissistic.35 If toxic leaders are “individuals whose behavior appears driven by self-centered careerism at the expense of their subordinates and unit,” then values-based leaders should display selfless intent that accentuates their subordinates’ and unit’s accomplishments.36 From recognition to mission completion, constructive leadership has to be about putting others first.

Close Match Between Espoused and Enacted Values. What leaders say and do matter. Leading by example requires both words and deeds. Organizations have missions that are girded by a vision that consists of ethics, standards, and goals for their members. An alignment of all these factors is needed to achieve a mission’s desired endstate. If people are our greatest resource, then leaders have to be good stewards of relationships. Followers and leaders work together better when they “are comfortable with each other, and value congruence is one way to achieve common ground.”37 Susan Fiske, John Cacioppo, and Reid Hastie remind us that “groups determine how behaviors associated with a task are to be accomplished in ways that conform to its core values.”38 A close match between what we believe in and what we do is significant, as novel situations tend to place us into contexts that require quick decisionmaking. Psychologist Gary Klein would state that quick, on-the-spot decisions come from habit, and we want our personal and professional habits to match our values and norms at both the organizational and individual levels.39

Airman provides security during training event for U.S. Army Alaska’s Warrior Leader Course on Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson, May 16, 2014 (DOD/Justin Connaher)

Capable Followers

In their literature review of the context of military environments, Fiske, Cacioppo, and Hastie posit that leadership is categorically not exclusively about the leader.40 Margaret Rioch states that almost all relationships “can be looked at as variations on the theme of leadership-followership.”41 If we believe that leadership is a process, we cannot extricate the fact that there is a transaction occurring between the leader and follower and both their respective perspectives and experiences. Because of this linkage, the leader is burdened with both creating and maintaining that relationship while also initiating and continuing communication and direction. However, it is of the utmost importance for a follower to be a good listener, be loyal, share the values of the leader and the group, and give honest feedback to better the experience. All of these qualities strengthen and enhance the leader-follower relationship while allowing for a bidirectional checks and balances system.

Upstanders. William O’Connell argues that it “takes true moral courage to risk a comfortable niche in the unit by advocating an unpopular idea.”42 One of the problems associated with followership is its negative connotation as being a weak, passive, or conforming position.43 Upstanders change that paradigm. Quite simply, upstanders are those who do not stand idly by in negative situations. In Padilla, Hogan, and Kaiser’s work, susceptible followers, in the form of colluders and conformers, are a part of a destructive environment. Robert Kelley defines four types of followers, noting that conformists are the “yes people” of organizations.44 He also defines “exemplary followers” as independent, innovative, and willing to question leadership.45 Upstanders take this one step further—they not only question leadership in their independence but also become a check to everyone in the organization, balance the system, and bring their own innovative solutions to the table when problems arise without prompt.

Lower Level Leadership. Leadership is not an amalgamation of characteristics that manifest within ourselves; it has to be externally confirmed by the experience of others. Rioch states that “the word leader does not have any sense without a word like follower implied in it.”46 But followers have a direct stake in the leading, as everyone is pushed in the direction of growth. Growth can be individual betterment or for the betterment of the group in the form of attaining the endstate. It should be understood that this does not mean that without lower level leadership, the leader-follower relationship fails. However, we propose that for the most optimal leadership exchange, followers must take a more responsible role in fostering a cohesive environment. Certain key roles are needed for good followership. “Second-in-command” is a followership role that allows the leader to be replaced if not around or when delegation is needed. A “sidekick” is an assistant who can relieve the burden of the leader while not filling an institutional position. “Partners” are an accompaniment to the leader and can allow a division of the responsibilities to be accomplished. In all of these important followership roles, we should view the follower not explicitly in a subordinate status. The leader-follower relationship is a two-way street.

Ranger Assessment Course instructor (right), informs class leader that he needs to improve leadership skills, Nevada Test and Training Range, October 3, 2014 (U.S. Air Force/Thomas Spangler)

Penchant for Proper Dissent. At the very onset, it may seem as if dissent goes against good order and discipline. However, Brian Gibson notes that there is likely “no more difficult calling for a military professional than to dissent.”47 In concert, O’Connell finds that junior leaders “can enhance mission effectiveness when they appropriately challenge the status quo.”48 It should be understood that superiors are in the best positions to deal with toxicity because they have the positional authority to counter it or deal with it in other appropriate means. However, George Reed argues that leaders “might be the last to observe the behavior unless they are attuned to it.”49 Though leaders should be wary, Reed’s thought places some of the burden back on the follower. We believe that followers owe their leaders the truth. As a unit creates upstanders, one of their key components is questioning leadership. Having a prudent and proper way of addressing those questions is the key.

Unity of Effort. An important objective regarding constructive leadership would be to promote small unit cohesion and other forms of teamwork. Research demonstrates that high-quality leader-member exchanges lead to less turnover, more positive evaluations, greater organizational commitment, greater participation, better job attitudes, and more support given to the leader.50 Interdependence leads to the achievement of a common goal. Group members who understand this interdependence gain greater insight into how they can facilitate trust and cooperation. Cohesion cannot be discounted, as it specifically speaks to willingness to remain a team and work within the team construct. Only by collaborating effectively with all members working in the same direction, if not the same task, can team members “truly gain the benefit of task accomplishment.”51

Equal Loyalty to Mission, Leadership, and Organization. Effective unit performance is a function of “the combined effect of the behaviors of individual unit members, to include leaders and those they lead; these behaviors take place both before and during defined missions.”52 The most effective followers are committed to the organization and to a purpose beyond themselves.53 Loyalty cannot just be to the leader, to those around us, or to the task at hand. Studies show that collective efficacy gained through loyalty “works harder on behalf of the group, sets more challenging goals, and persists in the face of difficulties and obstacles.”54 Horizontal allegiances (to peers and others in our unit) must match vertical allegiances (to the organization or subordinate entities), or effectiveness, trust, and even rationality are undermined.55

In their article Padilla, Hogan, and Kaiser state that “leadership can yield results ranging from constructive to destructive.”56 Here we draw the same conclusion, adding that the definition of constructive leadership emphasizes positive outcomes that not only lead organizations and their members to success but also have the capacity to be transformative in nature, changing a negative (toxic) environment to a positive one. Lieutenant General Walter Ulmer, USA (Ret.), stated that although we have been “alerted for years to the issue [of toxic leadership]; as an institution we have been reluctant to confront it directly.”57 Of note, constructive leadership is overly studied, but not in the context of being an active deterrent to toxicity; it should start to be studied more in terms of how relations among leaders, followers, and environments can combat seeds of negativity from growing. Our transformative triangle specifically addresses the elements of Padilla, Hogan, and Kaiser’s “toxic triangle” and suggests how an effective paradigm shift could foster the appropriate relationships for positive outcomes. JFQ

Notes

1 Joseph Doty and Jeff Fenlason, “Narcissism and Toxic Leaders,” Military Review (January–February 2013), 55. This article cites a study reporting that 80 percent of the officers and noncommissioned officers polled had observed toxic leaders in action and that 20 percent had worked for a toxic leader.

2 Art Padilla, Robert Hogan, and Robert B. Kaiser, “The Toxic Triangle: Destructive Leaders, Susceptible Followers, and Conducive Environments,” The Leadership Quarterly 18 (2007), 176–194. The authors use the terms toxic and destructive interchangeably.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Denise Williams, “Toxic Leadership in the U.S. Army,” U.S. Army War College Strategy Research Project, March 2005.

6 Padilla, Hogan, and Kaiser.

7 Ibid.

8 Shawn Anchor, “Positive Intelligence,” Harvard Business Review, January–February 2012, available at <https://hbr.org/2012/01/positive-intelligence>.

9 Susan Fiske, John Cacioppo, and Reid Hastie, The Context of Military Environments: An Agenda for Basic Research on Social and Organizational Factors Relevant to Small Units (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2014), 60.

10 John Steele, “Antecedents and Consequences of Toxic Leadership in the U.S. Army: A Two-Year Review and Recommended Solutions,” Center for Army Leadership, Technical Report 2011-3, 4.

11 Iain Hay, “Transformational Leadership: Characteristics and Criticisms,” Flinders University, 2006, 1.

12 Steele, 18.

13 Hay, 1.

14 Morton Ender and Remi Hajjar, “McDonaldization in the U.S. Army: A Threat to the Profession,” in The Future of the Army Profession, ed. Don M. Snider and Lloyd J. Matthews (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005), 15.

15 Michael Passer and Ronald Smith, Psychology: The Science of Mind and Behavior, 5th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2013).

16 Paul Arden, It’s Not How Good You Are, It’s How Good You Want to Be (New York: Phaidon Press, 2003), 42.

17 Ibid.

18 James O’Toole, Leading Change (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1995), 149.

19 Yan Ye, “Factors Relating to Teachers’ Followership in International Universities in Thailand,” Assumption University of Thailand, 2008, 1.

20 Steele, 14.

21 Ye, 2.

22 Kent Bjugstad, “A Fresh Look at Followership: A Model for Matching Followership and Leadership Styles,” Comcast Spotlight, 2006, 308.

23 John Maxwell, The 360° Leader (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, Inc., 2006), 244.

24 Paul Hanges, Lynn Offerman, and David Day, “Leaders, Followers, and Values: Progress and Prospects for Theory and Research,” The Leadership Quarterly 12 (2001), 129–131.

25 Patrick Sweeney, Mike Matthews, and Paul Lester, Leadership in Dangerous Situations: A Handbook for the Armed Forces, Emergency Services, and First Responders (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2011), 5–6.

26 Army Doctrine Publication (ADP) 6-22, Army Leadership (Washington, DC: Headquarters Department of the Army, 2014), available at <http://armypubs.army.mil/doctrine/DR_pubs/dr_a/pdf/adp6_22_new.pdf>.

27 Maxwell, 244–245.

28 Steele, 14.

29 Ibid.

30 O’Toole, 36.

31 Steele, 25.

32 Peter Northouse, Leadership: Theory and Practice (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2007), 129.

33 Ibid., 127.

34 ADP 6-22.

35 Doty and Fenlason, 55.

36 Walter Ulmer, “Toxic Leadership: What Are We Talking About,” Army (June 2012), 48.

37 Bjugstad, 307.

38 Fiske, Cacioppo, and Hastie, 34.

39 G.A. Klein, Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1998).

40 Fiske, Cacioppo, and Hastie, 59.

41 Margaret Rioch, “All We Like Sheep,” Psychiatry: Journal for the Study of Interpersonal Processes 34, no. 3 (1971), 258–273.

42 William O’Connell, “Military Dissent and Junior Officers,” in Concepts for Air Force Leadership, ed. Richard I. Lester (Maxwell AFB, AL: Air University Press, 1988), 326.

43 Bjugstad, 304.

44 Robert Kelley, “In Praise of Followers,” Harvard Business Review, November 1988, 142–148.

45 Ibid.

46 Rioch, 262.

47 Brian Gibson, “The Need for Proper Military Dissent,” U.S. Army War College Strategy Research Project, 2012, 7.

48 O’Connell, 324.

49 George Reed, “Toxic Leadership,” Military Review (July–August 2004), 71.

50 Northouse, 155.

51 Sweeney, Matthews, and Lester, 187.

52 Fiske, Cacioppo, and Hastie, 65.

53 Bjugstad, 308.

54 Sweeney, Matthews, and Lester, 189.

55 Ibid., 100.

56 Padilla, Hogan, and Kaiser, 190.

57 Ulmer, 50.