DOWNLOAD PDF

Colonel Aizen J. Marrogi, USA, MD, has served as a Surgeon General Liaison Officer to the Iraqi Ministry of Defense. Dr. Saadoun al-Dulaimi is serving his second tour as Iraqi Minister of Defense and is also the Minister of Culture.

Since its introduction by Joseph Nye, Jr., in 1990, soft power has been defined as “achieving desirable influence through attraction and cooperation,” as opposed to hard power, which rests on inducements or threats.1 Although the concept of soft power is not universally embraced,2 using economic, cultural, scientific, and healthcare resources can create a dominant soft power that, when carefully applied, might generate favorable behavior from other nations and their leaders and build enduring partnerships to promote regional and global security.

The healthcare sector is a diverse group of industries accounting for $2.8 trillion, or 17.8 percent, of the U.S. gross domestic product.3 It delivers direct health care through thousands of hospitals and other facilities and provides research and development for manufacturing pharmaceuticals, medical devices, and biotechnology. It is a research-intensive segment of the economy focusing on developing better methods for preventing, diagnosing, and treating life-threatening diseases, and it provides stability and prosperity in the form of millions of high paying jobs. It can also play a pivotal role in a U.S. asymmetric response to unpredictable challenges overseas, both directly through the care of patients and more generally in the economic benefits of expanding the healthcare sector in countries where unemployment and unfavorable socioeconomic factors contribute to radicalism.

Physicians are well regarded in many cultures, especially in the Arab and Muslim world. U.S. policy strategists can leverage this historic goodwill and use the diplomacy of medicine to reach out to Arab and Muslim countries, especially those undergoing Arab Spring transitions including Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Yemen, and even Syria. For countries such as Iraq that have shattered healthcare infrastructures, healthcare cooperation represents a unique opportunity to set their relationships with America on a more amicable and sustainable course.

Soldier checks blood pressure of Afghan in Kandahar Province, Operation Spartan Stork (U.S. Army/Kristina Truluck)

Medical Diplomacy and Engagement

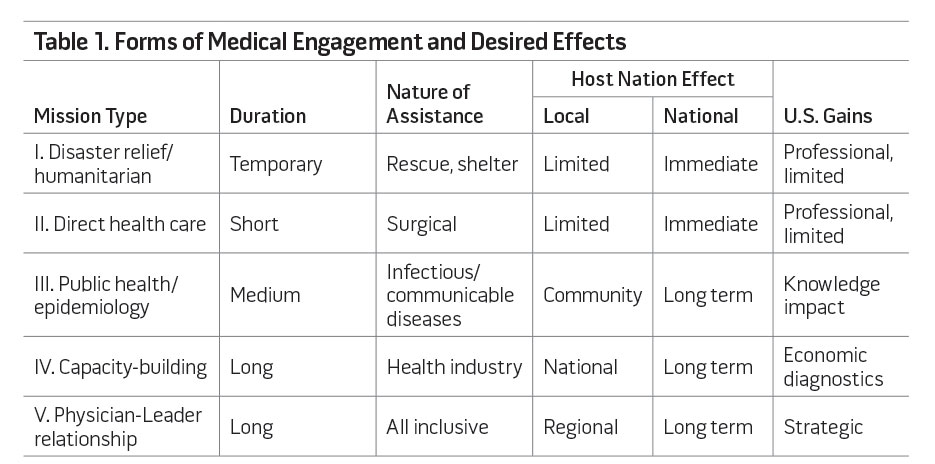

The diplomacy of medicine can achieve the dual goals of improving global health while helping repair failures in diplomacy, particularly in conflict areas, maturing theaters, and resource-poor countries. It can also represent a creative U.S. response to radical and fundamentalist propaganda that aims to inflame the Arab and Muslim world against the West. The instruments of this forward diplomacy are U.S.-trained physicians and other healthcare professionals serving as parts of U.S. missions or commands. Besides building goodwill within the population, they can gain access to decisionmakers in the host nations, providing a unique capability to engage and leverage the U.S. position. Table 1 summarizes forms of medical engagement and their desirable effects on host nations and on their relationship with Washington.

The United States is the largest global aid donor, spending nearly $50 billion for economic and military assistance in 2011. Some $14.1 billion was spent in support of U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) programs. Furthermore, institutions within the U.S. Government have a long and rich medical engagement tradition, which has left beneficial legacies. The Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Naval Medical Research Center, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, Fogarty International Center, and others have epitomized medical engagement as outlined in table 1 in the public health, epidemiology, and capacity-building areas (types III and IV). Their efforts focus on developing drugs and vaccines as treatments for infectious and communicable disease, training and mentoring international scientists in biomedical disciplines, and conducting epidemiological surveys in response to emerging medical threats. They deploy medical staffs and scientists to Central and South America, East Africa, Europe, Oceania, and East Asia to work alongside host nation counterparts in a Doctors Without Borders spirit, promoting U.S. ethical values. The Center for Disaster and Humanitarian Assistance Medicine, a congressionally funded organization within the Uniformed Services University, is an academic resource for humanitarian assistance and disaster response medicine through education, training, consultation, and scholarly activities.

Types I and II initiatives as seen in table 1 have constituted the bulk of U.S. medical engagements since the 1940s. The naval forces are frequently called on to respond to disasters, both natural and manmade, including floods (Cyclone Gervaise in Mauritius in 1975 and Typhoon Rita in the Philippines in 1978), earthquakes (Ionian and Volos islands of Greece in 1953 and 1955, respectively), ship crew and passenger/refugee rescues (Cuban flotilla repatriation to U.S. soil in 1977), storm relief efforts, and oil spill cleanup. In addition, more than 6,000 missions are carried out annually by hundreds of nongovernmental organizations at a cost of $250 million including surgical missions of craniofacial reconstruction, cataract extractions, and treatment of adult and pediatric acute and chronic diseases.

While these well-intended missions resonate favorably with the receiving community and gather instant political capital for U.S. policy- and decisionmakers, their enduring value is questionable since for many there is no objective measure of their performance.4 Furthermore, medical missions of this type can undermine local health systems since they rely on visiting volunteers, and there is limited possibility of long-period sustainment due to costs, schedule constraints, and complicated logistics.5 They also impose additional burdens on local health facilities and, in some cases, fail to follow host nation healthcare delivery standards.6 In an extensive review of 2,000 short-term medical missions, a study established the need for better planning and preparation in the areas of cross-cultural communication as well as the contextual realities of mission sites and coordination with host nation healthcare programs and transparency to ensure an optimal outcome.7 Other forms of medical relief and aid are delivered through specific efforts and initiative health programs such as the (U.S.) President’s Emergency Program for AIDS Relief, President’s Malaria Initiative, and Global Health Initiative, with some focusing on female and child health issues.

The Healthcare Sector and U.S. Economy

Table 2 compares two significant sectors of the U.S. economy, each representing a form of national power in terms of its ability to achieve success.

We do not advocate replacing the coercive nature of hard power with the soft power manifested by the health sector and others, but combining the two in pursuit of international relationships. The United States can dominate in any armed conflict, but it has also excelled in projecting its soft power with the help of governmental, academic, and commercial institutions to promote American culture, ideals, and values among willing partners. America and its allies decisively won World Wars I and II. Washington failed to engage its postconflict soft power quickly to help shattered Europe in the aftermath of World War I, but it offered assistance through the Marshall Plan after World War II with a completely different outcome. The Europeans have remained America’s staunchest allies in major international crises and confrontations including those arising during the Cold War and more recently the so-called war on terror.

The United States is engaged in modernizing the security forces of dozens of nations, providing them with weapons systems worth $66 billion in 2011. Half of that sum involves deals with Iraq and other Arab Gulf states,8 which admire the U.S. medical and healthcare system and aspire to acquire its capabilities. This industry should also be a significant part of the Foreign Military Sales (FMS) process. Medical components will help allies take care of their troops, who will be using American weapons systems. The arrangement will suggest the kind of relationship Washington seeks with its friends around the globe. America wants its allies to defend themselves while it simultaneously helps them care for their people who are injured in the line of duty. This message will resonate and cement long-term strategic alliances. Currently, the U.S. effort to modernize Saudi Arabia’s national guard is the only known such program where medical engagement plays a significant role. Success stories there will typify the desirable effects Washington might expect if it expands this approach into Iraq, Turkey, Egypt, Libya, and countries in the areas of responsibility of U.S. Pacific and U.S Africa Commands.

Budget Cuts and the Pivot to the Pacific

With the Department of Defense (DOD) facing a budget reduction of $500 billion over the next decade, the Nation must fundamentally rethink its engagement strategy.9 Washington will remain vitally interested in promoting democracy, peace, and stability in the Middle East once its conventional forces are withdrawn. The question is how to augment engagement with allies and keep influence when a conventional presence is reduced or withdrawn for logistical, political, or strategic reasons. Iraq represents such a challenge.

Moreover, in the fall of 2011 President Barack Obama announced plans to expand the U.S. role in the Asia-Pacific region. The fundamental goal underpinning the pivot or rebalancing toward this region has been to strengthen U.S. allies there, many of whom share U.S. values and beliefs, including a desire for a more forward American policy to counterbalance China’s growth as a military and economic power. Given the geographic enormity of this region, which constitutes 55 percent of the world’s territory, an increased U.S. military emphasis in the theater might result in reduced military capacity in other parts of the world, especially with budgetary constraints and the possible curbing of the U.S. Navy’s operational plans.10

Tool of Influence

Health care is among the highest needs of the citizens of the Third World and developing countries, who are burdened with infectious and communicable diseases. These needs are exacerbated by poor environmental sanitation, a shortage of safe drinking water, smoking, undernutrition, and limited access to preventive and curative health services. In addition, lack of education, gender inequality, and explosive population growth have overwhelmed what health services are available in some nations where the United States maintains a large military presence. Addressing these problems both among countries and within countries constitutes one of the greatest challenges of this century.

USNS Comfort anchored off Port-au-Prince, Haiti, during Operation Continuing Promise (U.S. Navy/ Eric C. Tretter)

To illustrate the usefulness and significance of forward medical diplomacy and engagement, we present three international players who have used this strategic form of power to enhance their standing abroad and among their constituents. Two are state players—Cuba and China—and the other consists of radical Islamic groups in the Middle East. In 1959, Cuban medical internationalism was introduced by Ernesto “Che” Guevara, the new government’s minister of health, and the country now deploys medical personnel overseas to deliver care and train host nations’ medical personnel. The largest medical school in the world, Escuela Latinoamericana de Medicina (ELAM), has an enrollment of over 8,000 students from the Third World.11 Furthermore, Cuban humanitarian missions and medical teams have been dispatched to Chile, Nicaragua, and Iran following earthquakes.12 Venezuela’s Mission Barrio Adentro (“Inside the Neighborhood”) program grew out of the emergency assistance Cuban doctors provided in the wake of the December 1999 mudslides in Vargas state.13 Although medical missions delivering health care have had limited impact, the remarkable aspect of this aggressive policy has been its sustainability, with more than 40,000 personnel (75 percent are health professionals) deployable to nearly 100 countries. This forward medical engagement has provided Cuba with symbolic capital (goodwill, influence, and prestige) well beyond its expected geopolitical influence. Although humanitarian principles are one reason for embarking on such a policy, promoting Havana’s image abroad and preventing international isolation are the likely driving factors. Cuba’s reestablishment of diplomatic relations with Guatemala in 1998 and Honduras in 2002 is a testimony of the success of its medical diplomacy and engagement strategy. Economically, Cuba’s earnings from medical engagement have exceeded $2 billion, or 28 percent of its total export receipts and net capital payments.14

While much has been said about China’s commercial push into Africa, a less-publicized facet of its foreign policy strategy has been “health diplomacy,” which has manifested itself in several medical engagement forms including the launching of the first hospital ship for the People’s Liberation Army Navy, Peace Ark. The majority of China’s foreign aid funds have gone into building hospitals and clinics, establishing malaria prevention and treatment centers, dispatching medical teams, training local medical workers, and providing medicine and equipment. By the end of 2009, China had built over 100 medical facilities, and some 30 additional hospitals are currently under construction; in addition, more than 1,000 health professionals are being trained on the African continent.15 By comparison, the United States managed to build one hospital in Basra, Iraq, after nearly 10 years of operations in the country. China may be the only country outside Cuba to send government-paid medical workers to live and practice in Africa for extended periods.16 The differences between Beijing and Washington when it comes to providing aid involve areas of transparency, staffing, and use of a sector focus not directly connected to other efforts. The United States ties its aid to human rights and correct governance.17 Partly because of these differences, China appears to have achieved more success with its aid programs in Africa even though many recipient nations feel more kinship with U.S. values. The Chinese government has also been able to win support from African countries on the international stage including in the United Nations (UN) and World Trade Organization.

The last of these international players that have adopted a medical diplomacy policy with resounding success are the radical Islamic elements in the Middle East including Hamas, Hizballah, and the Islamic Brotherhood of Egypt. An estimated 90 percent of Hamas activities revolve around “social, welfare, cultural, and educational activities” and, in particular, readily accessible healthcare services for the masses in the West Bank. The Muslim Brotherhood was founded in Egypt in 1928 and became a powerhouse and main opposition to President Hosni Mubarak’s regime in 2005 after it changed tactics by recruiting young physicians, engineers, and teachers to operate its schools and clinics. Hizballah started as a small militia but now has seats in the Lebanese government, a radio and a satellite television station, and ambitious programs for social development, allowing this shady group to emerge from the fringes of society to occupy center stage in world affairs. The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs noted that “Hezbollah not only has armed and political wings,” but also boasts an extensive social development program with hospitals and clinics providing affordable health care in southern Lebanon and West Beirut.

Medic conducts checks with Afghan children in Khowst Province (U.S. Army/Jason Epperson)

The Power of Medicine in U.S. Diplomacy

How can the United States bring this significant sector of its economy to play a pivotal role in achieving its global objectives of securing peace and stability, fighting radical ideological and religious groups, and promoting democracy? What can a U.S.-trained medical care provider in a health attaché/medical advisor role hope to accomplish?

A U.S.-trained provider or health attaché can play three major roles: shape the nature and environment of the U.S. mission senior diplomat or commander, be an advocate for the U.S. healthcare industry and practices, and act as an essential player in implementing existing security cooperation. As part of a mission, the provider would serve as an advisor to the mission chief or senior military leader on health matters related to U.S. personnel whether military, civilian, or contractor. When engaging host nations’ senior nonmedical and medical leaders as a source of assistance to the former group and advisor to the latter, the provider’s contributions can be an important way to showcase American values including ethical practices, competency, honesty, compassion, and respect for human dignity and rights.

Corpsman uses auto refractor during eye examination at Prince Ngu Hospital in Tonga during Pacific Partnership 2011 (U.S. Navy/Eli J. Medellin)

Under certain conditions, a medical provider can be the go-between, especially when the provider understands the culture of host nation counterparts and leaders. A physician or other healthcare provider has a unique relationship with leaders of other nations, sometimes in the doctor-patient context where trust and privacy can translate into better collaboration and mutual assistance between the nations. In Iraq, for example, a deployed U.S. provider through his excellent relationship with host nation authorities was able to obtain the country’s flu epidemiology response plan and information on a cholera epidemic and a small outbreak of typhoid, which helped him implement measures to protect U.S. personnel. Having a competent medical delivery system in a partner nation may augment U.S. military healthcare assets in time of combat, something the United States learned well during first Gulf War. Both authors recall several occasions where their relationships were key in clearing significant hurdles facing the U.S. mission in the host nation, the details of which are beyond the scope of this article.

Forward and aggressive medical engagement abroad will put adversaries on the defensive, diminishing their hard and soft power since they cannot compete with the achievements and outcome of U.S. health care in all of its sectors. During his deployment, a U.S. provider was asked daily about accessing U.S. medicine (drugs) by host nation leaders known to have an adversarial view of the United States but who did not hesitate to place their trust in U.S.-trained medical professionals when it came to their own and their families’ health.

Girl shows sister how to “open wide” as Peruvian navy lieutenant pulls tooth during Continuing Promise 2011 community service medical event at Polideportivo medical site in El Salvador (U.S. Air Force/Alesia Goosic)

The United States and its allies are involved in a global war to combat extremism and radicalism. Health diplomacy and engagement will bring America’s humane intentions and values closer to the masses, especially in cultures with a negative image of America. It should be an integral part of an asymmetric response using all the pillars of U.S. strength including both hard and soft components. U.S. medical providers can contribute immensely to the security assistance missions of the U.S. State and Defense Departments. So far, only the Saudi Arabian National Guard Modernization Program has managed to incorporate a senior healthcare provider within its ranks.

The Way Forward

To accomplish the concept described herein, the doctrine of medical diplomacy and engagement for the U.S. Government and military must be defined and developed as a joint concept. Stakeholders from DOD, the State Department, USAID, the healthcare industry, and perhaps some intelligence agencies should discuss rules of engagement and write a training manual with procedures for personnel to execute this vision. Most observers equate medical engagement with both military and civilian U.S. medical providers simply delivering health care to host nation citizens. This is not what we are promoting. We advocate a more forward medical policy as part of a wider application of other components of soft power such as education, commerce, and culture. U.S. military medical personnel should always be included as health attachés to serve in key U.S. missions overseas. Their goals should include coordinating with medical FMS cases to complement ongoing strategic efforts to advance peace and stability, build professional and personal relationships with both medical and nonmedical host nation leaders, and serve as advocates for U.S. health care in all of its phases including care, education, and research. One of the authors, Dr. al-Dulaimi, while serving in his official capacity as Iraq’s Minister of Culture, always emphasized the importance of the U.S. cultural attaché making his or her presence felt on the Iraqi cultural stage.

The United States is at a crossroads in searching for ways to stay engaged in a hostile world during a time of financial strain. U.S. medical commands must adapt to the changing environment and be in front of civilian and military leaders to help address their needs and shape the operational environment before, during, and after any decisive engagement. American medicine can be on the forefront of a new forward medical policy. It has the personnel, tools, and doctrine. It only needs the opportunity, the conviction, and the endorsement of all the stakeholders within and without the U.S. Government. JFQ

Notes

- Joseph S. Nye, Jr., Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics (New York: PublicAffairs, 2004).

- David Frum and Richard Perle, An End to Evil: How to Win the War on Terror (New York: Random House, 2004).

- Brent Jones, “Medical Expenses Have ‘Very Steep Rate of Growth,’” USA Today, February 4, 2010, available at <www.usatoday.com/news/health/2010-02-04-health-care-costs_N.htm>.

- Jesse Maki et al., “Health Impact Assessment and Short-Term Medical Missions: A Methods Study to Evaluate Quality of Care,” BMC Health Services Research 8, no. 121 (2008), available at <www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/8/121/>.

- Andrew D. Pinto and Ross E.G. Upshur, “Global Health Ethics for Students,” Developing World Bioethics 9, no. 1 (April 2009), 1–10.

- Stephen >Bezruchka, “Medical Tourism as Medical Harm to the Third World: Why? For Whom?” Wilderness and Environmental Medicine 11, no. 2 (2000), 77–78; P. Suchdev et al., “A Model for Sustainable Short-Term International Medical Trips,” Ambulatory Pediatrics 7, no. 4 (July–August 2007), 317–320.

- Alexandra L.C. Martiniuk et al., “Brain Gains: A Literature Review of Medical Missions to Low and Middle-Income Countries,” BMC Health Services Research 12, no. 134 (2012), available at <www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/12/134>.

- Thom Shanker, “U.S. Arms Sales Make Up Most of Global Market,” The New York Times, August 27, 2012.

- Leon Panetta, “Major Budget Decisions Briefing from the Pentagon,” press briefing, Washington, DC, January 26, 2012.

- M.E. Manyin, Pivot to the Pacific? The Obama Administration’s “Rebalancing” Toward Asia, RL 7-5700 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, March 2012).

- John M. Kirk and H. Michael Erisman, Cuban Medical Internationalism: Origins, Evolution, and Goals (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009).

- Robert Huish and John M. Kirk, “Cuban Medical Internationalism and the Development of the Latin American School of Medicine,” Latin American Perspectives 34, no. 6 (November 2007), 77–92.

- Charles L. Briggs and Clara Mantini-Briggs, “Confronting Health Disparities: Latin American Social Medicine in Venezuela,” American Journal of Public Health 99, no. 3 (March 2009), 549–555.

- Julie M. Feinsilver, “Oil-for-Doctors: Cuban Medical Diplomacy Gets a Little Help from a Venezuelan Friend,” Nueva Sociedad, no. 216 (July–August 2008).

- Charles W. Freeman III, project director, and Xiaoqing Lu Boynton, ed., China’s Emerging Global Health and Foreign Engagements in Africa (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, November 2011).

- JoAnne Wagner, “‘Going Out’: Is China’s Skillful Use of Soft Power in Sub-Saharan Africa a Threat to U.S. Interests?” Joint Force Quarterly 64 (1st Quarter 2012), 99–106.

- Deborah Bräutigam, “U.S. and Chinese Efforts in Africa in Global Health and Foreign Aid: Objectives, Impact, and Potential Conflicts of Interest,” in Freeman, 1–12.