Download PDF

Major Andrus W. Chaney, USA, is a Foreign Area Officer specializing in sub-Saharan Africa and is currently assigned to U.S. Army Africa. Previously, he was the Office of Security Cooperation Chief at the U.S. Embassy Djibouti.

In 2000, Commander Richard G. Catoire, USN, recommended creating a new commander in chief for Africa.1 Eight years later, his idea became a reality with the creation of U.S. Africa Command (USAFRICOM). In a decade since then, the new command has maneuvered through the challenges of establishing a new unit, the effects of the Arab Spring, and the growing terrorist threats of al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, Boko Haram, the so-called Islamic State, and al Shabaab in Somalia.

U.S. Air Force survival evasion resistance and escape specialist air advisor, with 818th Mobility Support Advisory Squadron, demonstrates navigation skills for Kenyan Defense Force members, Laikipia Air Base, Kenya, June 23, 2016 (U.S. Air Force/Evelyn Chavez)

In 2010, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates outlined his vision for the future of security cooperation: “This strategic reality demands that the U.S. government get better at what is called ‘building partner capacity’: helping other countries defend themselves or, if necessary, fight alongside U.S. forces by providing them with equipment, training, or other forms of security assistance.”2 Following this guidance, Defense Secretary Leon Panetta stated in 2012, “Whenever possible, we will develop innovative, low-cost, and small-footprint approaches to achieve our security objectives, relying on exercises, rotational presence, and advisory capabilities.”3 These two statements summarize USAFRICOM’s security cooperation efforts since 2008. Before 2012, security cooperation professionals serving in USAFRICOM used old strategies, policies, directives, publications, and combatant command campaign plans (CCCP) to execute security cooperation activities in Africa. USAFRICOM previously planned security cooperation efforts in stovepipes, without synchronized strategic effects across all staff levels.

USAFRICOM can better implement Department of Defense (DOD) security cooperation guidance by overcoming four obstacles. This article first reviews some challenges of establishing a new combatant command, notes the changes in security cooperation brought about by Secretary Gates, and highlights changes to security cooperation in the recent National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). The article next illustrates the systems USAFRICOM has established to operationalize its CCCP and identifies areas for further improvement. It then outlines specific areas where USAFRICOM and its components are succeeding in improving their efforts and identifies gaps for future improvement. Overall, this article highlights areas where USAFRICOM and its components are struggling with implementing the multitude of new guidance for DOD security cooperation efforts.

Challenges of a New Combatant Command

USAFRICOM is the newest of the six geographic combatant commands (GCCMDs) created in the last 45 years, excluding U.S. Northern Command. Over the last 45 years, other GCCMDs have had, on average, 15 rotations of commanders and Active-duty staff (3 years each) and 9 rotations of civilian staff assignments (5 years each). USAFRICOM received four commanders in its first 8 years, recently completed its first full rotation of civilian staff, published its third CCCP, and approved the second edition of its country cooperation plans. By these measures, USAFRICOM is still a young command.

USAFRICOM continues to improve itself by conducting necessary analysis and developing strategic plans to achieve the endstates outlined in the Nation’s strategic guidance. However, it historically has received a multitude of recommendations from the Government Accountability Office (GAO). A GAO report from 2010 concerning USAFRICOM’s efforts on the continent identified areas of needed improvement in training, planning, and interagency collaboration. These included the lack of overarching strategies such as a CCCP and country cooperation plans, the lack of measuring long-term effects of activities, and the lack of training on applying funding sources to activities by staff members on the patchwork of security cooperation authorities. It also highlighted that limited resources prevented the desired number of interagency personnel from participating on the USAFRICOM staff and that limited cultural knowledge and understanding of U.S. Embassy operations caused missteps during engagements.4 GAO also highlighted that program managers from other agencies failed to implement guidance from Presidential Policy Directive (PPD) 23, Security Sector Assistance. Not fully implementing this guidance has resulted in an inability to accurately track the distribution of program funding and a lack of agencies to coordinate and implement programs.5 Department of State program managers have since improved funding assessments and integrated more agencies into planning and executing programs.

U.S. Marine assigned to Special Purpose Marine Air-Ground Task Force Crisis Response–Africa watches as Ugandan soldier uses radio to relay messages, Camp Singo, Uganda, November 17, 2016 (U.S. Marine Corps/Alexander Mitchell)

In another report, GAO highlighted ongoing DOD reforms for security cooperation efforts but highlighted four significant unaddressed challenges.6 Of the six combatant commands reviewed, USAFRICOM, U.S. Pacific Command, and U.S. Southern Command required more work in at least 12 of the 20 identified deficient subtasks. A few examples of the deficiencies were that senior U.S. officials created unrealistic partner country expectations, the Theater Security Cooperation Management Information System (TSCMIS) provided an insufficient common operating picture of all security cooperation activities, and inaccurate cost estimates led to the cancelation of or reductions in the scope of a case.7 DOD addressed most of these deficiencies in the new policies, directives, and doctrine. However, others require significant changes in the knowledge management system, TSCMIS, and more training for security cooperation personnel.

Since 2012, there has been a gradual increase in new and updated strategies, policies, and regulations issued concerning security cooperation. This growth, primarily because of security force assistance (SFA) activities in Afghanistan and Iraq, resulted in 15 new publications for combatant commands to execute. President Barack Obama issued PPD 16, U.S. Strategy Toward Sub-Saharan Africa, in June 2012, and PPD 23, Security Sector Assistance, in 2013. From 2012 to 2017, DOD agencies collectively issued four new policy directives and one planner’s handbook, including security cooperation as the main subject.8

The Joint Staff and Headquarters Department of the Army issued or updated seven notes, pamphlets, field manuals, publications, or other guidance during the same period.9 In 2013, the Joint Staff issued Joint Publication Note 1-13, “Security Force Assistance,” which stated that “despite the importance of its national mission, SFA does not have a dedicated JP [joint publication] and existing joint doctrine makes only occasional references to it.” Four years later, JP3-20, Security Cooperation, was published. The 2015 U.S. National Military Strategy further defined the security cooperation and security assistance communities.

The release of these 15 documents within the last 6 years is connected to Secretary Gates’s vision. This vision, combined with the significant increase in SFA programs since 2006 and the consistent findings of the GAO, has led Congress to implement new strategies ensuring that DOD fully operationalizes its security cooperation efforts.

Changes in Security Cooperation

The National Defense Authorization Act of 2006 authorized DOD to use its Title 10 funding source instead of the Department of State’s Title 22 funding to support the Building Partnership Capacity of foreign militaries. This authorization allows DOD to assist other allied or partner nations in transferring training and equipment so long as they are in direct support of U.S. efforts to counter terrorism. This authorization was a “departure from vesting security assistance authorities in the Department of State and led to charges of a militarized foreign policy.”10 This significant shift in security assistance policy and authority undoubtedly laid the foundation for Secretary Gates’s 2010 vision of the future of DOD SFA activities.

This change created numerous issues for DOD staffs that are expected to execute this vision, especially since “the number of authorities and associated funding provided to DOD to conduct security cooperation activities has expanded significantly since 2001, with DOD security cooperation funding tripling from 2008 to 2015. In contrast, the Department of State’s security assistance funding has increased by 23 percent in the same period.”11 The Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA) and Security Cooperation Officers (SCO) have mainly experienced these effects.

DOD systems have felt this 23 percent increase in demand. “It has to be staffed,” DSCA director Vice Admiral Joseph Rixey remarked of the system. “If you look at the ways sales are going up, if workforce doesn’t correspond with sales going up, or at least stay steady, it’s going to have an obvious impact on time because you’re running everything through that particular system.”12 Overall, DOD continues to expect war on terror results from systems designed for Cold War–era timelines while cutting staffs by 20 percent and under the constant stress of unknown budget allocations.

U.S. Army instructor with soldier from Senegalese army’s 1st Paratrooper Battalion, as part of Africa Readiness Training 2016, Thies, Senegal, July 13, 2016 (U.S. Army Africa/Craig Philbrick)

Operationalizing Security Cooperation

Congress codified Secretary Gates’s vision through the 2016 NDAA. In section 1202, Congress mandated that DOD, “in consultation with the Secretary of State, shall develop and issue to the DOD a strategic framework for DOD security cooperation to guide prioritization of resources and activities.” It also directed that DOD discuss strategic goals of security cooperation programs; identify the primary objectives, priorities, and desired endstates of programs; identify challenges to achieving the objectives, priorities, and endstates; and develop a methodology for assessing the effectiveness of the programs.13 In response to these requirements, DOD developed policies and processes to improve security cooperation communities. These new changes became law in the 2017 NDAA. Four areas that the new legislation would focus on include streamlining security cooperation authorities, coordinating more between DOD and the State Department on security cooperation activities, improving monitoring and evaluation of security cooperation activities, and increasing the professionalism of the security cooperation workforce.14

With the 2017 NDAA, these directives and instructions have become law. For USAFRICOM staff members, these new directives and changes in the NDAA 2017 resulted in new requirements without the systems or trained staff to accomplish these tasks. With these challenges, how does USAFRICOM implement new DOD policies and laws and improve our security cooperation efforts?

Obstacles to Operationalizing the CCCP

Security cooperation efforts require detailed plans that are synchronized with congressional funding cycles and that are capable of being executed over multiple years and through various program managers. It is DOD policy that security cooperation activities “shall be planned, programmed, budgeted, and executed with the same high degree of attention and efficiency as other integral DOD activities.”15 However, operations tend to receive the full attention of the staff because officers are more familiar with them. Operations have a clear and defined task, purpose, and timeline. Security cooperation is about building relationships, sometimes with “difficult” partners who have a say in what we do. To fully operationalize security cooperation, USAFRICOM must overcome four obstacles: institutionalize new processes, institutionalize all programs in the CCCP, reduce the number of events, and increase training for its staff.

Institutionalize New Staff Processes. USAFRICOM has begun establishing CCCP line-of-effort boards to synchronize all combatant command and component staffs’ security cooperation efforts and programs into five defined areas. This allows the boards to prioritize USAFRICOM efforts, resulting in synchronizing efforts through the issuance of operation orders for security cooperation events. U.S. Army Africa (USARAF), which is USAFRICOM’s Army component command, has further operationalized this by initially establishing an 18-step system to achieve full staff integration and support the CCCP. Neither of these new staff processes has achieved a full execution of their cycles, nor are they fully integrated into a written and published standard operating procedure.

USAFRICOM’s orders are not synchronized with the requirements of its components’ timelines and requirements. USARAF regularly receives the order to execute security cooperation programs just weeks before the new fiscal year, and not within the 180-day requirement by U.S. Army Forces Command to task regionally aligned forces. USAFRICOM should challenge its line-of-effort boards to produce operation orders that include all security cooperation events and send these orders to its components 270 days before the start of the new fiscal year.

With any new staff procedure, time is required to synchronize efforts fully. Over the upcoming years, USAFRICOM and USARAF should continue to refine their staff processes and integrate them into a codified system that outlasts staff changeovers. In doing so, USAFRICOM will reduce its staff’s learning curve, provide the time required to task allocated forces correctly, and comply with the new requirements from the 2017 NDAA by fully accessing every security cooperation event.

Institutionalize All Programs in the CCCP. USAFRICOM must include in the CCCP all State Department programs and DOD units that operate in its area of operation but are not directly assigned. For example, DSCA is responsible for the Defense Institutional Reform Initiative, Africa Center for Strategic Studies (ACSS), and Ministry of Defense Advisor (MoDA) programs. These programs and center execute activities in the USAFRICOM area of operations, yet none are captured or directed in the CCCP. Neither are the State Department’s Foreign Military Financing (FMF) and International Military Education and Training (IMET) programs. To synchronize these efforts, the CCCP should become the sole directive for all security cooperation efforts in the combatant command’s area of operations, including the National Guard Bureau’s State Partnership Programs. Likewise, the CCCP should become the tool through which USAFRICOM directs FMF and IMET funding by showing the desired long-term effect of State Department security assistance.

Republic of Mali airman trains with U.S. Soldiers, Airmen, and partner nations during aerial logistics and resupply Exercise Atlas Accord 2012, Mopti Airfield, Sevare, Mali, February 6, 2012 (U.S. Army/Callie West)

Reduce the Number of Military-to-Military Events. The impact of military-to-military events is rarely measured and accessed due to their small size (two to three personnel), small effect (3 to 4 days), and sheer numbers (more than 100). Instead of trying to do something in every country in Africa, USAFRICOM should make its staff and components do fewer events with more synchronization and more effects afterward. These events should be longer, with more personnel, more expected outcomes, and more synchronization of efforts with allied partners. If these efforts were synchronized with other programs over several years, these small touch points could be included in the larger assessment of an overall effort.

Increase the Professionalism of the Security Cooperation Workforce. To ensure security cooperation funds are spent properly, USAFRICOM must ensure its personnel are properly trained and staffed. DSCA is primarily responsible for the professional development of the security cooperation workforce, and does this through resident and online training courses by its Defense Institute of Security Cooperation Studies (DISCS). Security cooperation professionals need more than a few weeklong courses to understand the complexities of their jobs. The fact that the Service branches conduct their own security cooperation courses highlights the previous lack of training opportunities from DISCS. Both the Army and Marine Corps have separate security cooperation planner courses. Since DISCS recently expanded and updated its training curriculum, USAFRICOM should code each billet properly to ensure its staff is properly trained through DISCS. As well, DISCS should absorb the U.S. Army and Marine Corps Planner’s courses to include Service-specific processes.

Overcoming these four obstacles to operationalizing the CCCP will not be accomplished easily or quickly. They may not be realized for several years because significant coordination and buy-in from within DOD and the State Department are required. However, without overcoming these issues first, none of the following three recommendations will be achieved.

Improve Coordination Efforts with Allies

Synchronizing security cooperation efforts with our strategic partners in Africa is ongoing at the highest and lowest levels. These efforts sometimes end in meeting notes, but without any credible action taken. As military budgets decrease, our militaries are forced to look for ways to synchronize our efforts. North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) doctrine is designed to enhance interoperability as the primary defense against aggression. In addition to operationalizing interoperability, we need to operationalize our security cooperation efforts. This concept is directly in line with all DOD policies and directives recently released.

USAFRICOM participates in multiple initiatives that help synchronize its efforts with allied nations. Specifically, USAFRICOM participates in the Sahel Multilateral Planning Group, which synchronizes allied activities in the Sahel Maghreb region, the Multinational Joint Task Force to synchronize efforts in the Lake Chad Basin to counter Boko Haram, and the East Africa Multilateral Planning Group to synchronize efforts in East Africa. These efforts have shown some progress. However, these efforts were previously restricted by the lack of headquarters staff synchronization. USAFRICOM is attempting to expand staff synchronization through the Defense Systems Information Agency’s All Partners Access Network, but even this system has its limitations to synchronizing with other knowledge management systems. For example, USAFRICOM’s component planners selectively participate in these groups, and when they do, few overarching action agreements are operationalized due to a lack of understanding of their capabilities, operations, and security cooperation systems. USAFRICOM could overcome these shortcomings by focusing its understanding on France and Great Britain’s efforts and by identifying ways that we can further synchronize our efforts.

France’s security cooperation efforts fall into two broad categories: structural and operational. The structural category has a long-term planning horizon of 5 to 10 years. This category includes activities such as building a military academy or a demining unit (building partnership capacity) and is executed by embedded trainers and advisors. These advisors live full time in the country for 2 years and wear the rank and uniform of the partner nation, something DOD normally does not do. The operational category includes activities such as peacekeeping pre-deployment training, and short-term police and border security training events. A majority of France’s security cooperation efforts in Africa are with its former colonial nations.

In 2008, France released its first defense white paper since 1994. In it, France explained that its security cooperation mission was to develop the capacity of its partner nations to respond to crises and support peacekeeping operations led by regional or subregional organizations.16 France further defined its goals for security cooperation efforts in Africa in its 2013 white paper: “Support for establishment of a collective security architecture in Africa is a priority of France’s cooperation and development policy.”17 Collaboration between the United States and France in operational efforts is increasing in Africa, particularly in West and Central Africa; however, security cooperation efforts are minimally integrated, and mainly at the Embassy level, among security cooperation officers.

The British army is currently undergoing a significant shift in its forces called “Army 2020.” Part of this change is identifying priority regions for defense engagement (security cooperation), and another important change is the creation of regionally aligning brigades.18 Great Britain, like the United States, recognized that aligning units to regions of the world is a smart approach, especially when downsizing an army. The chief of general staff for the British army commented on this in a report in 2014, stating that the “U.S. Regionally Aligned Forces programme is the most advanced of these and one that we are very conscious we need to work alongside, complement, and collaborate with such that our activities are reinforcing rather than interfering.”19

A recent example of collaboration is the peacekeeping training for Malawi Defence Forces that were trained by British and U.S. soldiers for deployment to the Democratic Republic of the Congo in support of a United Nations mission. Our efforts can go further with the British by synchronizing more with the four British regionally aligned brigades. Recent staff talks between the U.S. and British armies show potential to synchronize our efforts in some nations. However, it will take more than yearly staff talks to synchronize efforts in Africa. To further expand our efforts, USARAF recently hosted a British army delegation to increase interoperability and collaboration by establishing routine staff-level discussions. Agreements were made to provide each other common operating pictures and to invite British army participants into USARAF’s annual order and multiyear planning cycles. Establishing operational planning teams that focus on specific aspects of planning will achieve the required collaboration to synchronize efforts. Additionally, by including the British army’s regional brigade representatives, USARAF will enable effective planning for several different engagements across multiple regions and achieve DOD guidance.

Senior ranking members of our allied nations are members of USAFRICOM’s Multinational Coordination Center. This center is the channel through which USAFRICOM continues to improve its synchronization efforts. This center should be more than liaison officers. The USAFRICOM commander must empower them, and so should their commands, to coordinate throughout the breadth and depth of USAFRICOM security cooperation efforts. Additionally, USAFRICOM can improve our efforts with the British and French by including them in our annual security cooperation conferences, reducing the classification of certain documents, and coordinating staff talks between the British, French, and USAFRICOM’s other component commands. These efforts will move away from security cooperation officers and components trying to accomplish the interoperability of efforts between two nations and toward full staff synchronization of all our efforts. It will also allow our African partners to benefit from a coordinated and cohesive security cooperation strategy.

Create a New CCCP Line of Effort

Defense institution-building (DIB) by USAFRICOM has been minimal and focused on the individual instead of the institution. In Africa, the primary programs through which DIB is executed are through the ACSS, Counterterrorism Fellowship Program, and Defense Institutional Reform Initiative, which primarily are only seminars and conferences. Additionally, professional military education through the IMET program has been provided on a limited scale in comparison to other combatant commands.

Defense institution-building (DIB) by USAFRICOM has been minimal and focused on the individual instead of the institution. In Africa, the primary programs through which DIB is executed are through the ACSS, Counterterrorism Fellowship Program, and Defense Institutional Reform Initiative, which primarily are only seminars and conferences. Additionally, professional military education through the IMET program has been provided on a limited scale in comparison to other combatant commands.

DOD guidance outlines what planners should take into account when deciding whether to support an event: “Security cooperation planners shall consider the economic capabilities of the foreign country concerned. Except in cases of the primary military considerations, an improvement of military capabilities that the partner country cannot or will not support, safeguard, or sustain shall be discouraged.”20 Planners in USAFRICOM and USARAF face a complicated decision when including these economic considerations into security force assistance proposals because most African nations struggle to sustain the equipment available through the DSCA Foreign Military Sales system. Providing less sophisticated equipment and focusing more on improving their defense institutions could go further in improving the capabilities of our partner nations.

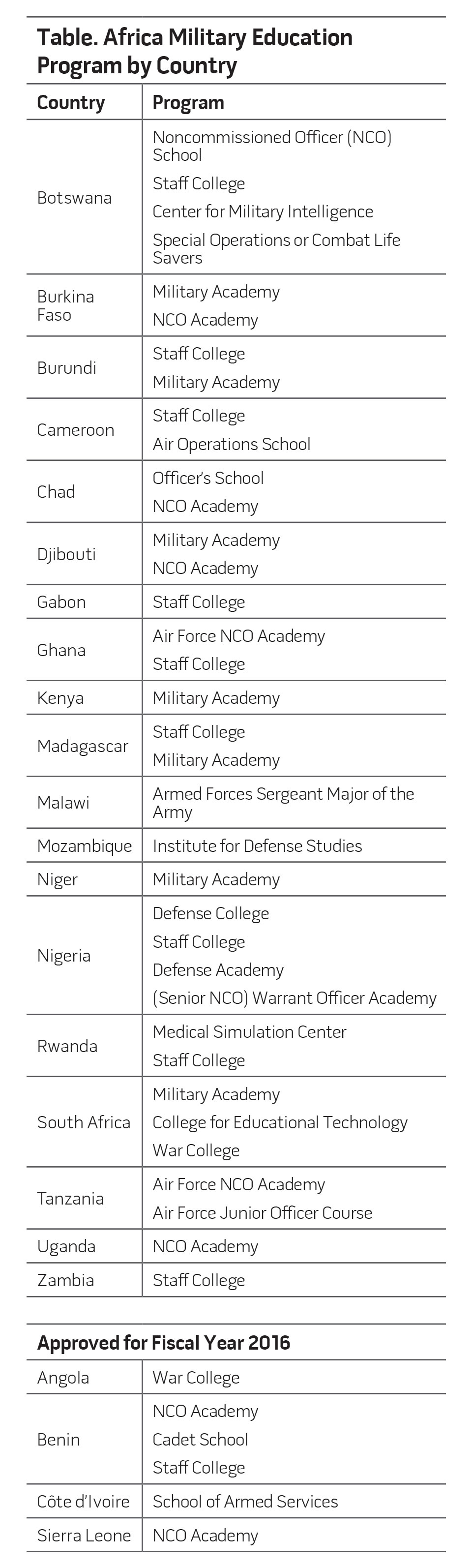

President Bill Clinton envisioned the Africa Center to “be a regional center modeled after the George C. Marshall Center in Germany designed in consultation with African nations and intended to promote the exchange of ideas and information tailored specifically for African concerns.”21 The Africa Center is currently achieving President Clinton’s vision, but it is not as successful as the Marshall Center. The center limits itself to primarily being a strategic institution significantly contributing to the academic community and reports to congressional leaders when required; however, most of its information is duplicative of other think tanks that cover Africa. The center seemingly is unaffiliated with USAFRICOM based on an analysis of its activities compared with other regional centers and collaboration with their respective combatant commands. The Africa Center currently executes one of eight components of DIB for DOD with its Africa Miltary Education Program (AMEP). This program is directed by the State Department and mandated by the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy for ACSS to serve as the executive agent. Under the AMEP mandate, ACSS partners with 19 nations for 32 programs. The USAFRICOM commander should refocus this organization to concentrate more on synchronizing and leading its DIB efforts in Africa at the executive direction and generating forces levels. The Africa Center could become the bridge between DSCA DIB programs and USAFRICOM’s effects.

USAFRICOM should request the expansion of the DSCA MoDA and AMEP programs. Currently, there are dozens of MoDAs in Afghanistan, but only one in all of Africa. The AMEP program is poorly funded at only $3 million a year—less than the amount spent on one of the dozens of tactical-level counterterrorism events. USAFRICOM could employ up to 20 new MoDAs in Africa and expand its DIB efforts into every military institution in Africa for the price of one of these events.

USAFRICOM encounters three programmatic obstacles to executing DIB in Africa, one of which was solved by the recent changes in the 2017 NDAA. Previously, 1-year programs, otherwise noted as “1-year money,” limited too many DOD security cooperation programs. This resulted in limited returns because many programs required long horizons with long-term growth returns. Therefore, the 1-year money cycle was ineffective for DIB in Africa because it takes more than 1 year to implement changes in defense institutions.

Thanks to Chapter 16, Section 333, of the new NDAA, events can now span multiple years. This solves the 1-year money issue. However, the new section requires each event to have a supporting institutional capacity-building requirement, which is often confused with DIB. This new requirement further highlights the second and third programmatic obstacles: defining DIB and available forces to execute DIB. Few SCOs or component staff officers are trained to access and develop DIB proposals at the ministerial level, which is currently done by DSCA, through the Defense Institute Reform Initiative. Because of this, some staff members regularly refer to generating or operation force activities incorrectly as DIB activities. This causes confusion of the intent of the event and the program through which it should be executed. The new requirement under Section 333 also creates the expectation that USARAF, which is USAFRICOM’s primary executor of security cooperation in Africa, can plan these DIB requirements. USARAF’s primary executor of security cooperation is the Regionally Aligned Brigade, which is not capable of performing DIB as defined by DOD Directive 5205.82, Defense Institution Building. The potential effects of these issues are SFA proposals not meeting the requirements under the new NDAA, poorly developed and executed events, and missteps with partner nations.

By establishing a new CCCP line of effort, USAFRICOM can focus its DIB efforts. This will drive guidance given to the Africa Center, assign DIB efforts to the appropriate executor, and expand ministry-level effects with our partner nations. Lastly, it will synchronize DIB efforts across all security cooperation programs, including the new mandated NDAA requirements.

Cameroonian soldiers, along with U.S. and Spanish marine advisors assigned to Africa Partnership Station 13, simulate amphibious assault in jungle as part of final exercise, Limbe, Cameroon, October 2013 (U.S. Marines/Tatum Vayavananda)

One System for Security Cooperation Efforts

DOD Directive 5132.03, DOD Policy and Responsibilities Relating to Security Cooperation, mandates the use of the Global Theater Security Cooperation Management Information System (G-TSCMIS) as the system for security cooperation activities. DOD recently published another new instruction fully updating and outlining its assessments, monitoring, and evaluation policy; it directed USAFRICOM to “ensure security cooperation initiatives are appropriately assessed and monitored, including by ensuring that appropriate data [are] entered into G-TSCMIS.”22 The 2017 NDAA also directs implementing new monitoring and evaluation systems.

USAFRICOM security cooperation officers work primarily through three knowledge management systems: DSCA’s FMF-IMET Budget Web Tool, into which budget requests, FMF future projected requirements, and IMET future requests are entered; the Overseas Humanitarian Assistance Shared Information System, into which all humanitarian assistance, humanitarian mine action, exercise-related construction, and humanitarian civil action programs are entered; and DSCA’s Security Cooperation Information Portal, where all Foreign Military Sales to their host nation are tracked. G-TSCMIS is not synchronized with any of these systems. USAFRICOM efforts to comply with this DOD directive will be further complicated because few SCOs have access to G-TSCMIS due to disconnects between DOD and State Department IT systems. Additionally, some DOD agencies and SCOs execute events that are never captured in G-TSCMIS.

As directed by DOD, G-TSCMIS is now being used by most security cooperation practitioners, and ideally any monitoring and evaluation systems should also be a part of this system. Some units have created their own assessment systems because of the lack of assessment capability by G-TSCMIS. For example, USARAF is using the Strategic Management System to create and track its assessments. This system does not synchronize with G-TSCMIS, nor will SCOs or other component desk officers have access to it. Continuing with this system will mean that different components could execute DOD assessment guidance with its own system. This will result in limited input and access and will also result in multiple assessments that are not synchronized within USAFRICOM.

USAFRICOM should work with the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense (DASD) for Security Cooperation to merge the many security cooperation knowledge management systems into G-TSCMIS to achieve the full intent of the new DOD instruction. DASD Security Cooperation should work with the State Department’s Bureau of Political-Military Affairs and Bureau of African Affairs to learn from their new monitoring and evaluation systems, which would provide better guidance to USAFRICOM’s staff. Doing so would significantly improve USAFRICOM efforts to operationalize security cooperation by providing a common knowledge management system and a common assessment system for its activities and effects. This would inform USAFRICOM’s CCCP efforts and drive changes as required. Overall, knowledge management and monitoring and evaluation systems are the two significant capability gaps USAFRICOM must solve to fully operationalize the 2017 NDAA and all the new DOD directives.

USAFRICOM’s lack of operationalization of its security cooperation processes, combined with the sheer size of its area of responsibility and the significant changes with the new NDAA, create unique challenges. This article outlined four main areas where USAFRICOM can improve its efforts to operationalize and synchronize its security cooperation efforts. First, improving efforts to operationalize the combatant command campaign plan will result in security cooperation events that are fully staffed and synchronized with other events to create multiple effects. Second, synchronizing efforts with allied nations, notably France and Britain, will result in a common approach to security cooperation in Africa, burden-sharing across NATO Allies, and greater effects with our partner nations. Third, creating a new CCCP line of effort for DIB will result in developing a long-term approach to many of the security-sector issues in Africa and provide space for democracies to grow and develop. Finally, adhering to DOD directives on G-TSCMIS will assist in operationalizing the CCCP by providing a holistic assessment to USAFRICOM’s security cooperation efforts, and will reduce learning curves by new staff members through providing a common knowledge management system. JFQ

Notes

1 Richard G. Catoire, “A CINC for Sub-Saharan Africa? Rethinking the Unified Command Plan,” Parameters (Winter 2000/2001), available at <http://strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/pubs/parameters/articles/00winter/ catoire.htm>.

2 Robert M. Gates, “Helping Others Defend Themselves,” Foreign Affairs, May 2010, available at <www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2010-05-01/helping-others-defend-themselves>.

3 Sustaining U.S. Global Leadership: Priorities for 21st Century Defense (Washington, DC: Department of Defense [DOD], January 2012), available at <http://archive.defense.gov/news/Defense_Strategic_Guidance.pdf>.

4 Defense Management: Improved Planning, Training, and Interagency Collaboration Could Strengthen DOD’s Efforts in Africa, GAO-10-794 (Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office [GAO], July 28, 2010), available at <www.gao.gov/products/GAO-10-794>.

5 Combating Terrorism: State Department Can Improve Management of East Africa Program, GAO-14-502 (Washington, DC: GAO, June 17, 2014), available at <www.gao.gov/products/GAO-14-502>.

6 Security Assistance: DOD’s Ongoing Reforms Address Some Challenges, but Additional Information Is Needed to Further Enhance Program Management, GAO-13-84 (Washington, DC: GAO, November 2012), available at <www.gao.gov/products/GAO-13-84>.

7 Ibid.

8 DOD Directive (DODD) 5132.03, DOD Policy and Responsibilities Relating to Security Cooperation, December 29, 2016; DODD 5205.82, Defense Institution Building, January 27, 2016; DOD Instruction (DODI) 5132.14, Assessment, Monitoring, and Evaluation Policy for the Security Cooperation Enterprise, January 13, 2017; Office of the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Plans and Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, Theater Campaign Planning: Planner’s Handbook, vol. 1 (Washington, DC: DOD, 2012).

9 Joint Publication 3-20, Security Cooperation, Revision Second Draft (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, 2015); Field Manual 3-22, Army Support to Security Cooperation (Washington, DC: Headquarters Department of the Army, January 2013); Pamphlet 11-31, Army Security Cooperation Handbook (Washington, DC: Headquarters Department of the Army, February 6, 2015); Army Regulation 11-31, Army Security Cooperation Policy (Washington, DC: Headquarters Department of the Army, March 21, 2013); Pamphlet 12-1, Security Assistance Procedures and Operations (Washington, DC: Headquarters Department of the Army, March 31, 2016); Joint Doctrine Note 1-13, Security Force Assistance (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, April 29, 2013).

10 Nina M. Serafino, Security Assistance Reform: “Section 1206” Background and Issues for Congress, RS22855 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, December 8, 2014), available at <https://fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/RS22855.pdf>.

11 Melissa Dalton, “Reforming Security Cooperation,” Defense360, July 15, 2016, available at <www.defense360.csis.org/reforming-security-cooperation/>.

12 Aaron Mehta, “Officers Sound Alarm on Foreign Sales Workforce,” Defense News, September 12, 2016, available at <www.defensenews.com/articles/officers-sound-alarm-on-foreign-sales-workforce?utm_source=Sailthru>.

13 House Armed Services Committee, National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2016, H.R. 1735, 114th Cong., 2015–2016, available at <www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/1735>.

14 Melissa Dalton, “Reforming Security Cooperation for the 21st Century: What the FY17 NDAA Draft Bill Gets Right, and the Challenges Ahead,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 9, 2016, available at <www.csis.org/analysis/reforming-security-cooperation-21st-century>.

15 DODD 5132.03.

16 Défense Et Sécurité Nationale Le Livre Blanc, June 2008, available at <www.ladocumentationfrancaise.fr/var/storage/rapports-publics/084000341.pdf>.

17 White Paper on Defence and National Security 2013 (Paris: Ministry of Defense, 2013).

18 Ministry of Defence, “Transforming the British Army: An Update,” July 2014, available at <www.army.mod.uk/documents/general/Army2020_Report_v2.pdf>.

19 General Sir Peter Wall, Defence Engagement: The British Army’s Role in Building Security and Stability Overseas (London: Chatham House, March 12, 2014), available at <www.chathamhouse.org/sites/files/chathamhouse/home/chatham/public_html/ sites/default/files/20140312Defence Engagement.pdf>.

20 DODD 5132.03.

21 DODD 5200.34, George C. Marshall Center for Security Studies, November 25, 1992, available at <www.marshallcenter.org/mcpublicweb/en/59-cat-english-en/cat-explore-gcmc-en/13-art-gcmc-about-dod-directive-en.html>; Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Africa Military Education Program Staff Brief to U.S. Army Africa Staff,” April 28, 2017.

22 DODI 5132.14, Assessment, Monitoring, and Evaluation Policy for the Security Cooperation Enterprise, January 13, 2017.