DOWNLOAD PDF

General Joseph L. Votel, USA, is the Commander of U.S. Special Operations Command. Lieutenant

General Charles T. Cleveland, USA (Ret.), is a former Commander of U.S. Army Special Operations

Command. Colonel Charles T. Connett, USA, is Director of the Commander’s Initiatives Group at

Headquarters U.S. Army Special Operations Command. Lieutenant Colonel Will Irwin, USA (Ret.), is a

resident Senior Fellow at the Joint Special Operations University.

In the months immediately following the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon in the autumn of 2001, a small special operations forces (SOF) element and interagency team, supported by carrier- and land-based airstrikes, brought down the illegitimate Taliban government in Afghanistan that had been providing sanctuary for al Qaeda. This strikingly successful unconventional warfare (UW) operation was carried out with a U.S. “boots on the ground” presence of roughly 350 SOF and 110 interagency operatives working alongside an indigenous force of some 15,000 Afghan irregulars.1 The Taliban regime fell within a matter of weeks. Many factors contributed to this extraordinary accomplishment, but its success clearly underscores the potential and viability of this form of warfare.

Special operations forces are extracted from mountain pinnacle in Zabul Province, Afghanistan, after executing air-assault mission to disrupt insurgent communications (U.S. Army/Aubree Clute)

What followed this remarkably effective operation was more than a decade of challenging and costly large-scale irregular warfare campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq employing hundreds of thousands of U.S. and coalition troops. Now, as Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom have come to an end, the defense budget is shrinking, the Armed Forces are drawing down in strength, and support for further large-scale deployment of troops has ebbed. Our nation is entering a period where threats and our response to those threats will take place in a segment of the conflict continuum that some are calling the “Gray Zone,”2 and SOF are the preeminent force of choice in such conditions.

The Gray Zone is characterized by intense political, economic, informational, and military competition more fervent in nature than normal steady-state diplomacy, yet short of conventional war. It is hardly new, however. The Cold War was a 45-year-long Gray Zone struggle in which the West succeeded in checking the spread of communism and ultimately witnessed the dissolution of the Soviet Union. To avoid superpower confrontations that might escalate to all-out nuclear war, the Cold War was largely a proxy war, with the United States and Soviet Union backing various state or nonstate actors in small regional conflicts and executing discrete superpower intervention and counter-intervention around the globe. Even the Korean and Vietnam conflicts were fought under political constraints that made complete U.S. or allied victory virtually impossible for fear of escalation.

After more than a decade of intense large-scale counterinsurgency and counterterrorism campaigning, the U.S. capability to conduct Gray Zone operations—small-footprint, low-visibility operations often of a covert or clandestine nature—may have atrophied. In the words of one writer, the United States must recognize that “the space between war and peace is not an empty one”3 that we can afford to vacate. Because most of our current adversaries choose to engage us in an asymmetrical manner, this represents an area where “America’s enemies and adversaries prefer to operate.”4

Nations such as Russia, China, and Iran have demonstrated a finely tuned risk calculus. Russia belligerently works to expand its sphere of influence and control into former Soviet or Warsaw Pact territory to the greatest degree possible without triggering a North Atlantic Treaty Organization Article 5 response. China knows that its assertive actions aimed at expanding its sovereignty in the South China Sea fall short of eliciting a belligerent U.S. or allied response. Iran has displayed an impressive degree of sophistication in its ability to employ an array of proxies against U.S. and Western interests.

While “Gray Zone” refers to a space in the peace-conflict continuum, the methods for engaging our adversaries in that environment have much in common with the political warfare that was predominant during the Cold War years. Political warfare is played out in that space between diplomacy and open warfare, where traditional statecraft is inadequate or ineffective and large-scale conventional military options are not suitable or are deemed inappropriate for a variety of reasons. Political warfare is a population-centric engagement that seeks to influence, to persuade, even to co-opt. One of its staunchest proponents, George Kennan, described it as “the employment of all the means at a nation’s command, short of war, to achieve its national objectives,” including overt measures such as white propaganda, political alliances, and economic programs, to “such covert operations as clandestine support of ‘friendly’ foreign elements, ‘black’ psychological warfare, and even encouragement of underground resistance in hostile states.”5

Organized political warfare served as the basis for U.S. foreign policy during the early Cold War years and it was later revived during the Reagan administration. But, as Max Boot of the Council on Foreign Relations observed, it has become a lost art and one that he and others believe needs to be rediscovered and mastered.6 SOF are optimized for providing the preeminent military contribution to a national political warfare capability because of their inherent proficiency in low-visibility, small-footprint, and politically sensitive operations. SOF provide national decisionmakers “strategic options for protecting and advancing U.S. national interests without committing major combat forces to costly, long-term contingency operations.”7

Human Domain-Centric Core Tasks for SOF

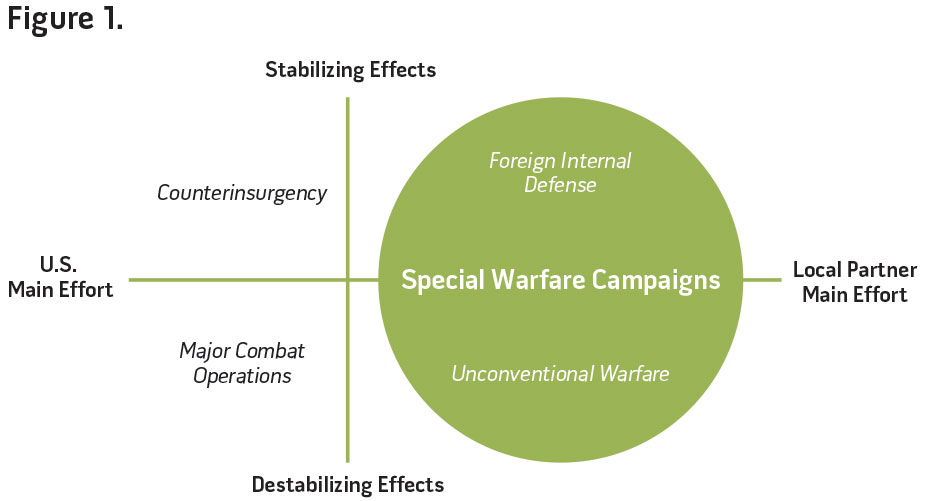

SOF provide several options for operating in the political warfare realm, especially those core tasks that are grouped under the term special warfare. Foreign internal defense (FID) operations are conducted to support a friendly foreign government in its efforts to defeat an internal threat. In terms of strategic application, UW represents the opposite approach, where the U.S. Government supports a resistance movement or insurgency against an occupying power or adversary government.

Both of these special warfare tasks rely heavily on SOF ability to build trust and confidence with our indigenous partners—host nation military and paramilitary forces in the case of FID, irregular resistance elements in the case of UW—to generate mass through indigenous forces, thus eliminating the need for a large U.S. force presence (see figure 1). It is this indigenous mass that helps minimize strategic risk during Gray Zone operations: “Special Warfare campaigns stabilize or destabilize a regime by operating ‘through and with’ local state or nonstate partners, rather than through unilateral U.S. action.”8 As described in a recent RAND study, discrete and usually multi-year special warfare campaigns are characterized by six central features:

- Their goal is stabilizing or destabilizing the targeted regime.

- Local partners provide the main effort.

- U.S. forces maintain a small (or no) footprint in the country.

- They are typically of long duration and may require extensive preparatory work better measured in months (or years) than days.

- They require intensive interagency cooperation; Department of Defense (DOD) elements may be subordinate to the Department of State or the Central Intelligence Agency.

- They employ “political warfare” methods to mobilize, neutralize, or integrate individuals or groups from the tactical to strategic levels.9

Many examples exist of successful long-duration, low-visibility U.S. SOF-centric FID operations in Latin America, Asia, and Africa. From 1980 through 1991, U.S. support to the government of El Salvador fighting an insurgency in that country included an advisory force that never exceeded 55 personnel. The conflict ended with a favorable negotiated settlement. Similar successes against lower level insurgencies took place in neighboring Honduras and Guatemala. More recently, U.S. SOF have played a central role in effective long-term FID efforts conducted in support of the governments of Colombia and the Philippines.

Less well known and understood by those outside of SOF is the core task of unconventional warfare.

Doctrine

This year marks the release of the first joint U.S. doctrine publication for the planning, execution, and assessment of UW operations.10 The United States has been producing UW doctrine since the first series of field manuals published from 1943 to 1944 by the wartime Office of Strategic Services (OSS). However, for the past seven decades, that doctrine has been produced by the U.S. Army. Despite the longstanding recognition in Army doctrine that UW is inherently joint and interagency in character, single-Service doctrine is at a disadvantage in reaching joint and interagency audiences. Therefore, a joint UW publication was needed.

Army Special Forces remain the only element in the U.S. Armed Forces organized, trained, and equipped specifically for UW. However, while Special Forces continue to play a central role in the mission, Joint Publication 3-05.1, Unconventional Warfare, recognizes the roles of other SOF, as well as important supporting functions of conventional forces. It also provides insight into the importance of interagency planning, coordination, and collaboration; other U.S. Government departments and agencies are not only frequently involved, but they are also often in the lead.

Unconventional warfare is fundamentally an indirect application of U.S. power, one that leverages foreign population groups to maintain or advance U.S. interests. It is a highly discretionary form of warfare that is most often conducted clandestinely, and because it is also typically conducted covertly, at least initially, it nearly always has a strong interagency element. It can be subtle or it can be aggressive. The U.S.-indigenous irregular benefactor-proxy relationship, if successful, achieves mutually beneficial objectives (although there can also be divergent interests between benefactor and proxy).

Advocates of UW first recognize that, among a population of self-determination seekers, human interest in liberty trumps loyalty to a self-serving dictatorship, that those who aspire to freedom can succeed in deposing corrupt or authoritarian rulers, and that unfortunate population groups can and often do seek alternatives to a life of fear, oppression, and injustice. Second, advocates believe that there is a valid role for the U.S. Government in encouraging and empowering these freedom seekers when doing so helps to secure U.S. national security interests.

Historically, the U.S. military has conducted UW primarily in wartime to assist indigenous resistance movements in defeating or causing the withdrawal of a foreign occupation force. In peacetime, UW can take the form of covert paramilitary operations conducted by other agencies of the U.S. Government or clandestine military operations. Through diplomacy, development, and other means, other government departments and agencies, such as the Department of State and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), can help shape the environment or provide support to resistance in other ways. When Congress passed the Boland Amendment during the 1980s, halting all but humanitarian U.S. aid to the Contras, USAID became the leading provider of support to the Nicaraguan resistance.

If a resistance movement or insurgency exists within a country whose government threatens U.S. security interests, the movement asks for assistance from the United States, and the group’s operational methods and behavior are deemed to be acceptable by the U.S. Government, the President of the United States might approve initiation of UW operations. The target government could be a state sponsor of terrorism or a proliferator of weapons of mass destruction technology. It might be a government engaged in ethnic cleansing or other crimes against humanity, or a state that willingly allows transit or provides sanctuary or other forms of support to terrorists. Or it could be a state that actively and aggressively, even belligerently, takes action to expand its territorial sovereignty with the result of undermining regional stability.

Under certain circumstances, the prudent employment of coercive force, by empowering an indigenous opposition element, can force a target government to do something it might not otherwise be inclined to do. Under other conditions, the goal could be simply to disrupt certain operations or activities of the hostile government, such as interfering with proliferation actions, safeguarding a population group targeted for genocide by the incumbent regime, or imposing extraordinary and unexpected difficulties in consolidating the occupation of a country that has been invaded, thus altering the adversary state’s cost and risk calculus.

This was the case during the prolonged U.S. UW campaign in support of Tibetan resistance fighters against Chinese occupiers from 1957 to 1969, and again with the UW operation in support of the Mujahideen in Afghanistan in their struggle against the Soviet 40th Army after its invasion and occupation of that country. During the second Reagan administration, however, the objective of the Afghanistan mission changed from a cost-imposing strategy to forcing the withdrawal of Soviet forces from the country. The success of that mission had enormous political and historical ramifications, beginning a chain of events that eventually resulted in the collapse of the Soviet Union and an end to the Cold War.

In some cases, UW can be used as a regime change mechanism, enabling an indigenous resistance or insurgent group to overthrow the existing government. In a wartime supporting role, UW operations can be a shaping effort in support of larger, conventional force operations, such as the very successful UW operations executed by U.S. SOF with Kurdish Peshmerga forces in northern Iraq during the 2003 invasion of that country. Alternatively, it could be the main effort in a military campaign, as was the UW operation that brought down the Afghan Taliban regime in 2001.

Unconventional warfare has often been the option of choice in situations where the President (or a theater commander in wartime) wishes to initiate operations much sooner than could be accomplished with the mobilization, preparation, and deployment of conventional forces. Such was the case with the operation by the 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne) and Air Force Special Tactics operators in Afghanistan in 2001.

A requirement might exist for operations in areas not easily accessible to conventional forces or that lend themselves to UW in an economy of force role in secondary theaters of war. Circumstances such as this resulted in several UW operations during World War II, including those in Yugoslavia, Albania, Greece, northern Italy, Norway, Burma, Thailand, Indochina, and China. In conducting such operations, U.S. forces will typically support three main elements of the resistance movement or insurgency—the underground, auxiliary, and guerrilla force. The underground is a cellular-based organization that operates in urban or other areas usually inaccessible to the guerrilla force. Composed of part-time volunteers, the auxiliary component clandestinely provides a wide range of support to both the underground and guerrillas. Probably the most familiar element is the guerrilla force, an organization of irregular combatants who comprise the armed or overt military component of the resistance.

Often the resistance includes a shadow government within the country capable of performing government functions on behalf of the movement. There might also be a government-in-exile in another country—often as a result of being displaced by an invading and occupying power—which remains the internationally recognized government of the occupied state. Nearly all the countries of Western Europe overrun and occupied by German forces in World War II established governments-in-exile in London.

Methods used by the resistance in meeting its objectives could include subversive activities such as mass protests, work slowdowns or stoppages, boycotts, infiltration of government offices, and the formation of front groups. These activities are primarily aimed at undermining the military, economic, psychological, or political strength or morale of the government or occupation authority.

Sabotage can be a means of physically damaging the government’s military or industrial production facilities, economic resources, or other targets. During World War II, sabotage targets for Allied SOF included road and rail lines of communication, hydroelectric power production and distribution facilities, telecommunications facilities, canal locks, radar sites, port facilities, factories engaged in the manufacture of war materiel, and military supply dumps or other targets.

Guerrilla warfare operations are carried out against military or other security forces to reduce their effectiveness and negatively impact the enemy’s morale. Allied-supported World War II guerrilla operations in occupied France, Belgium, and Holland, as well as those in the Philippines, were instrumental in facilitating Allied ground campaigns.

U.S. Air Force CV-22 Osprey’s primary mission in 8th Special Operations Squadron is insertion, extraction, and resupply of unconventional warfare forces (U.S. Air Force/Jeremy T. Lock)

Many types of information activities are used to influence friendly, adversary, and neutral audiences. Resistance groups craft narratives that best convey the movement’s purpose and leverage key grievances of importance to the people. Another important purpose of information operations could be to encourage disparate resistance factions to work together to achieve common objectives.

Because the FID and UW core tasks are so closely related, employing many similar capabilities, a comprehensive Gray Zone special warfare campaign could include aspects of both missions, thus capitalizing on their synergistic effect. Among the U.S. objectives in initiating support to the Nicaraguan resistance in the early 1980s, for example, was to aid the U.S. FID program in El Salvador by pressuring the Nicaraguan Sandinista government to halt its support to the Salvadoran Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front.11

Today, “regional powers such as Russia, China, India, Indonesia, Brazil, Nigeria, South Africa, Turkey, and Iran assert growing power and influence. . . . Sub-state actors (e.g., clans, tribes, ethnic and religious minorities) seek greater autonomy from the central government.”12 The complex nature of the future operating environment will often render traditional applications of the diplomatic and economic instruments ineffective or inappropriate. Decisionmakers might wish to avoid the political risks and consequences, including escalation and mission creep, associated with direct military engagement. At such times, UW might be the only viable option through which the U.S. Government can indirectly achieve political objectives. By supporting indigenous insurgencies, resistance movements, or other internal opposition groups, the U.S. Government can employ UW as a strategic tool of coercion, disruption, or to lead to the defeat of a hostile regime.

An Enigmatic History

U.S. UW doctrine has evolved from its World War II roots when the Allies conducted UW in at least 18 countries worldwide. Operations by U.S. forces include a highly successful UW campaign in an “economy of force” role in Burma and operations by stay-behind guerrilla leaders in the Philippines, where UW proved invaluable to U.S. land forces during the liberation of that country. Probably the best prepared UW operations were conducted in the European theater, where Allied SOF benefited from an extensive and well-tested UW command and sustainment infrastructure, to say nothing of state-of-the-art training and equipment.

On May 25, 1940, when the German defeat of France seemed all but inevitable, the British Chiefs of Staff met to consider possible courses of action. Once France fell, they believed, Britain’s only hope lie in rescue by the as yet immobilized United States. Until that time, “the best hope would lie in subversion, to rot the enemy-held countries from within.”13 Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who saw great value in helping the people of occupied Europe to play an active part in their own liberation, signed the charter for the Special Operations Executive (SOE) in July 1940.

Four years later, Special Force Headquarters, an Allied UW command subordinate to General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s theater command and staffed by the British SOE and the U.S. OSS, along with Free French and other Allied personnel, deployed several types of special forces into denied territory in occupied Europe. Among the better known units were the multinational Jedburgh teams. Deployed in support of the French Resistance, “Jed” teams were primarily assigned the dual mission of organizing, equipping, training, and advising guerrilla forces; and serving as a communication link between the Resistance and the Allied high command in London. But they served an additional purpose that was just as important, though seldom mentioned and largely unheralded.

Many Jedburgh veterans later testified that they spent much of their time preventing the various resistance factions—each with different postwar political agendas and often violently opposed to one another—from fighting each other and keeping them focused on the common enemy, the German occupiers.14 One need look no further than Syria today to imagine how much more difficult the Allied ground campaign to liberate France might have been had this internecine rivalry not been held in check. With all of their tactical and operational successes, the Jedburghs’ greatest strategic contribution might have been in keeping the tenuous French Forces of the Interior coalition intact, making the Jeds truly warrior-diplomats. Eisenhower later wrote of the work of the Jedburghs and other SOE and OSS special forces: “In no previous war, and in no other theater during this war, have resistance forces been so closely harnessed to the main military effort.”15

Unconventional warfare continued to play a significant role in U.S. foreign policy during the early Cold War years, often in the form of covert paramilitary operations led by the Central Intelligence Agency. Military UW conducted during the Korean War was only minimally effective, primarily because of a lack of training and experience on the part of those charged with executing it.

In April 1961, President John F. Kennedy had to weather the politically embarrassing failure of the ill-advised Bay of Pigs affair in Cuba. Secretly working at a military base in Guatemala under the guise of a mission to train Guatemalan forces, U.S. Army Special Forces trained the rebel force of Cuban exiles in small unit guerrilla warfare operations.16 Unfortunately, those forces were then employed in an inappropriate manner, attempting a conventional amphibious landing and beach assault against superior forces.

Throughout the Cold War, many hard lessons were learned in places as wide-ranging as Eastern Europe, China, Indonesia, Tibet, North Vietnam, Nicaragua, and elsewhere. One major success came during the 1980s with support provided to the Afghan Mujahideen that resulted in expulsion of Soviet occupation forces from that country.

The post–Cold War era brought two major UW successes for U.S. forces. First came the operation to oust the Taliban regime in Afghanistan in late 2001, described at the beginning of this article. The second was the UW operation in northern Iraq that contributed to victory during the 2003 U.S. invasion of that country.

Civil Resistance

Today’s joint UW doctrine recognizes variances of resistance that span the breadth of organized opposition from reform-oriented social movements17 to social revolution,18 to insurgency, and on to larger armed revolutionary movements.

Recently, there has been growing interest in UW operations that leverage existing social movements and nonviolent, civil resistance–based social revolution. Contributing to this interest is the favorable track record of such movements in comparison with armed resistance. Based on one recent study of 323 resistance movements whose objective was regime change or expulsion of a foreign occupation force between 1900 and 2006, those movements following a strategy of “nonviolent resistance against authoritarian regimes were twice as likely to succeed as violent movements.”19

The main reason for this is that movements choosing to follow a nonviolent strategy attract a much larger domestic support base than armed and violent movements. While even the most successful of the armed variety hope to attract a support base numbering in the tens of thousands, supporters numbering in the hundreds of thousands for nonviolent resistance campaigns are not unusual. Moreover, nonviolent movements find it much easier to garner backing from the international community, so important in building coalition UW support.

Figure 2 (created by the Naval Postgraduate School’s Doowan Lee) illustrates the relationship between social movements, social revolution, and unconventional warfare. An example of the scenario depicted by sector G at the center of the diagram can be seen in U.S. support provided to resistance elements during Serbia’s “Bulldozer Revolution” that resulted in the overthrow of dictator Slobodan Milosevic, then president of what remained of Yugoslavia.

When massive demonstrations in September 1999 demanded Milosevic’s resignation, he responded with a brutal crackdown by police and the army. One opposition group, however, remained determined to oust Milosevic through a campaign of nonviolent civil disobedience. Otpor (Serbian for resistance), an underground Serbian youth movement formed in 1998 by a dozen college students, eventually grew to a nationwide grassroots popular movement claiming a membership of more than 70,000.20 The Bill Clinton administration decided to support the movement and provided much in the form of funding, computers, and political and military advice.

The domestic anti-Milosevic campaign culminated in October 2000 with a nationwide general strike and a march on the capital by hundreds of thousands of protesters from across the country. Milosevic finally announced his resignation the following day, bringing to an end a brutal 13-year regime.

For several reasons, SOF are ideally suited to contribute to U.S. support to such social revolutions. First and foremost, it must be remembered that just because a movement opts to follow a nonviolent strategy is no guarantee that the revolution will remain nonviolent. Several of the Arab Spring revolutions have shown that such movements must be prepared in the event that severe government repressive measures drive them to abandon the nonviolent strategy and resort to an armed resistance campaign rather than forfeiting their cause. In fact, in the case of Serbia’s Bulldozer Revolution, some elements of the resistance were prepared to do just that had it become necessary.

Participants at a recent UW/Resistance seminar (co-sponsored by U.S. Special Operations Command Europe and Joint Special Operations University) at the Baltic Defence College in Estonia observed that, based on the experiences of some former Warsaw Pact nations in their civil resistance–based post–Cold War revolutions, “resistance can be armed or non-violent, but both must be planned for.”21

Clearly, SOF have a traditional UW role in providing the necessary organizing, equipping, training, and advising functions to support such an armed resistance effort, but this role can have a much greater chance of succeeding if SOF are involved as advisors early on, during the nonviolent resistance campaign. Whether early U.S. support is covert or overt, if it reaches the point where lead-agency responsibility transfers from the Department of State or another government agency to DOD, early involvement by SOF can ensure that such a transfer is smooth and is executed at full speed, much like the passing of a baton in a relay race, rather than a dangerous and counterproductive stop-and-go affair. SOF capabilities and expertise transcend lead-agency boundaries.

An early decision to support a movement can also pay dividends, providing the opportunity for SOF or other U.S. Government departments or agencies to influence, shape, and steer the movement; encourage and facilitate the consolidation or alliance of competing but compatible factions; or thwart or inhibit the development of competing factions or movements that are incompatible and adversarial.

DOTMLPF Implications

Much is already being done toward developing or upgrading joint and Service UW-related doctrine, and better organizing and preparing our primary UW force. While some doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leader development, personnel, and facilities (DOTMLPF) requirements have been identified and solutions determined, full implications should continue to emerge through a rigorous and disciplined requirements assessment process.

In recognizing a need for doctrine updating, one Theater Special Operations Command commander recently observed:

The conditions of 2014 are different than those of 1944, and the tools with which unconventional warfare is waged today differ greatly. We must advance from the nostalgic vision of remote guerrilla bases in denied territory and adapt to a world of split-second communications and data transfer, non-violent resistance, cyber and economic warfare, and the manipulation of international law to undermine national sovereignty. . . . In our era, unconventional warfare is more likely to take the form of a civil resistance movement, perhaps manipulated by foreign powers, that seeks to provoke a violent government response in order to destroy that government’s legitimacy in the eyes of the international community. Waging and countering this new unconventional warfare demands great sophistication and agility.22

Implementation of emerging UW concepts and doctrine requires persistent, low-visibility presence around the world and the development of a network of useful and influential contacts. Foreign internal defense, security assistance, foreign officer exchange programs, foreign education and study opportunities, and special assignments are important means of contributing to this.

To meet the challenges of UW support to social movements or social revolution, a deeper understanding of the dynamics of civil resistance and how UW can be conducted through such subversive (and often nonviolent) movements is required. Understanding conditions where more violent methods might be problematic, if not counterproductive, calls for an in-depth understanding of the theories, concepts, and methods associated with social movement influence, mobilization, and activism. SOF must continually work to upgrade their training regimen and education curriculum in areas such as:

- social movement theory

- regional history, cultural studies, and language proficiency

- creation and preparation of an underground

- cyber UW tools and methods

- influence operations

- negotiation and mediation skills

- popular mobilization dynamics

- subversion and political warfare

- social network analysis and sociocultural analysis.

To make a thorough assessment of a group and to be in a position to capitalize on the advantages of early observation and possible engagement, SOF should be capable of recognizing the conditions and early indicators of resistance.

Materiel requirements are such that they apply to other SOF core tasks as well as UW. Senior leaders have long recognized that SOF require improvements in denied area penetration and standoff capabilities and an ability to perform critical core tasks for extended periods in high-risk situations.23 The requirement for low-visibility and stealthy air platforms might not be limited to infiltration, exfiltration, and personnel recovery. Modified versions of these platforms could serve as tankers or gunships, or platforms for information operations, aerial resupply, precision strike, and terminal guidance.

Materiel requirements might also include a stealthy, long-endurance SOF drone with global surveillance and strike capability. Other payloads could provide the capability to disseminate electronic messages via radio or television broadcast, in standoff mode, to target audiences in denied areas. Unmanned aerial systems might also have the ability to emplace remote unattended ground sensors capable of detecting, classifying, and determining the direction of movement of personnel, wheeled vehicles, and tracked vehicles.

A Critical Policy Gap

After a few early political warfare successes in the 1950s, along with some clear failures, President Eisenhower once considered appointing a National Security Council (NSC)-level “director of unconventional or non-military warfare,” with responsibilities including such areas as “economic warfare, psychological warfare, political warfare, and foreign information.”24 In other words, he saw the need for an NSC-level director of political warfare, someone to quarterback the habitually interagency effort. This need still exists to achieve unity of effort across all aspects of national power (diplomatic, informational, military, and economic) across the continuum of international competition. As Max Boot has observed, political warfare has become a lost art which no department or agency of the U.S. Government views as a core mission.25

Jedburghs get instructions from briefing officer in London, 1944 (U.S. Office of Strategic Services)

Conclusion

Unconventional warfare, whether conducted by the United States or Russia or any other state seeking to advance national interests through Gray Zone proxy warfare, has a rich history but continues to evolve to meet changing global conditions. One certainty in a world of continuing disorder, a world bereft of Cold War clarity and relative “stability,” where globalization has enabled almost continuous change, is that the UW mission must continue to adapt and so must those responsible for executing it.

U.S. forces can likely have the greatest chance for success in Gray Zone UW operations when engaged early in a resistance movement’s development and continuously thereafter. As demonstrated in the U.S. operation to support Afghanistan’s Northern Alliance in 2001, however, it can also succeed with relatively mature and experienced resistance groups, when a benefactor state’s support might be just enough to tip the scales in favor of a movement that has been largely stalemated.

One remaining requirement is that of determining what Gray Zone UW success looks like and establishing meaningful criteria for measuring the effectiveness of such operations. The very concept of “winning” must be fundamentally reexamined in the context of a future environment where we will likely not commit large military formations in decisive engagements against similarly armed foes.

A Gray Zone “win” is not a win in the classic warfare sense. Winning is perhaps better described as maintaining the U.S. Government’s positional advantage, namely the ability to influence partners, populations, and threats toward achievement of our regional or strategic objectives. Specifically, this will mean retaining decision space, maximizing desirable strategic options, or simply denying an adversary a decisive positional advantage.

In these human-centric struggles, our successes cannot be solely our own in that they must be largely defined and accomplished by our indigenous friends and coalition partners as they realize respectively acceptable political outcomes. Successful culmination of Gray Zone conflicts will not be marked by pomp and ceremony, but rather should, ideally, pass with little or no fanfare or indication of our degree of involvement.

History has shown that no two UW situations or solutions are identical, thus rendering cookie-cutter responses not only meaningless but also often counterproductive. Planners and operators most in demand in this difficult task will be those capable of thinking critically and creatively, warriors unhindered by the need for continuous and detailed guidance. Such special operators will be most capable of performing critical UW tasks under politically sensitive conditions, ensuring that they can serve, in the tradition of their Jedburgh predecessors, as true warrior-diplomats. JFQ

Notes

1 Doug Stanton, Horse Soldiers: The Extraordinary Story of a Band of U.S. Soldiers Who Rode to Victory in Afghanistan (New York: Scribner, 2009), 347; and George Tenet, with Bill Harlow, At the Center of the Storm: My Years at the CIA (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2007), 225.

2 See, for example, General Joseph L. Votel, statement before the House Armed Services Committee Subcommittee on Emerging Threats and Capabilities, March 18, 2015; Captain Philip Kapusta, U.S. Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) white paper, “Defining Gray Zone Challenges,” April 2015; David Barno and Nora Bensahel, “Fighting and Winning in the ‘Gray Zone,’” War on the Rocks, May 2015; and Nobuhiru Kubo, Linda Sieg, and Phil Stewart, “Japan, U.S. Differ on China in Talks on ‘Gray Zone’ Military Threats,” Reuters, March 10, 2014.

3 Nadia Schadlow, “Peace and War: The Space Between,” War on the Rocks, August 2014, available at <http://warontherocks.com/2014/08/peace-and-war-the-space-between/>.

4 Ibid.

5 George F. Kennan, “Policy Planning Staff Memorandum,” May 4, 1948, National Archives, RG 273, Records of the National Security Council, NSC 10/2, available at <http://academic.brooklyn.cuny.edu/history/johnson/65ciafounding3.htm>.

6 Max Boot and Michael Doran, Council on Foreign Relations Policy Innovation Memorandum No. 33, Political Warfare (Washington, DC: Council on Foreign Relations, June 7, 2013).

7 USSOCOM, Special Operations Forces Operating Concept, May 2013, 1.

8 Dan Madden et al., Special Warfare: The Missing Middle in U.S. Coercive Options (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2014), 1.

9 Ibid., 2.

10 Joint Publication (JP) 1-02, Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, November 8, 2010, as amended through October 15, 2015), defines unconventional warfare as “activities conducted to enable a resistance movement or insurgency to coerce, disrupt, or overthrow a government or occupying power by operating through or with an underground, auxiliary, and guerrilla force in a denied area.”

11 David Ronfeldt and Brian Jenkins, The Nicaraguan Resistance and U.S. Policy (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 1989), 15.

12 USSOCOM, SOF Operating Concept, 2.

13 William Mackenzie, The Secret History of S.O.E.: Special Operations Executive, 1940–1945 (London: St. Ermin’s Press, 2000), xix.

14 Will Irwin, The Jedburghs: The Secret History of the Allied Special Forces, France 1944 (New York: PublicAffairs, 2005), 236, based on correspondence and interviews with more than 60 U.S., British, and French Jedburgh veterans from 1985 to 2005.

15 General Dwight D. Eisenhower, letters to the executive director of SOE and to the director of the Office of Strategic Services London, May 31, 1945. See Irwin, xxii, 280.

16 Central Intelligence Agency History Staff, Official History of the Bay of Pigs Operation, Vol. 2: Participation in the Conduct of Foreign Policy, October 1979 (declassified July 25, 2011), 57–98.

17 JP 3-05.1, Joint Special Operations Task Force Operations (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, April 26, 2007), defines social movement as “a collective challenge by people with common purposes and solidarity in sustained interactions with elites, opponents, and authorities.”

18 JP 3-05.1 defines social revolution as “a rapid transformation of a society’s state and class structures, accompanied and in part accomplished through popular revolts.”

19 Erica Chenoweth and Maria J. Stephan, “Drop Your Weapons: When and Why Civil Resistance Works,” Foreign Affairs 93, no. 4 (July/August 2014), 94–106.

20 Roger Cohen, “Who Really Brought Down Milosevic?” New York Times Magazine, November 26, 2000, available at <www.nytimes.com/2000/11/26/magazine/who-really-brought-down-milosevic.html>.

21 U.S. Special Operations Command Europe (USSOCEUR) and Joint Special Operations University (JSOU), “Unconventional Warfare/Resistance Seminar Series After Action Report,” November 2014, 3.

22 USSOCEUR, “Sponsor Welcoming Remarks Prepared for COMSOCEUR,” JSOU–BALTDEFCOL–SOCEUR Unconventional Warfare Seminar, Tartu, Estonia, November 4–6, 2014.

23 See General Bryan D. Brown, then–Deputy Commander, USSOCOM, testimony before the Senate Committee on Armed Services Subcommittee on Emerging Threats and Capabilities on the State of Special Operations Forces, April 9, 2003, 12; and Michael G. Vickers, “Transforming U.S. Special Operations Forces,” Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, prepared for OSD Net Assessment, August 2005, 11.

24 National Security Council memorandum, “Discussion at the 209th Meeting of the National Security Council, Thursday, August 5, 1954,” August 6, 1954; Eisenhower Presidential Library; Papers as President (Ann Whitman File), NSC Series, Box 5.

25 Boot and Doran.