DOWNLOAD PDF

In the last decade, our foreign policy has transitioned from dealing with the post–Cold War peace dividend to demanding commitments in Iraq and Afghanistan. As those wars wind down, we will need to accelerate efforts to pivot to new global realities. We know that these new realities require us to innovate, to compete, and to lead in new ways. Rather than pull back from the world, we need to press forward and renew our leadership.

—Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, 2011

Imagine that you are the fire chief for a mid-sized community. The city council informs you that it is reducing your budget this year by 30 percent. It is redirecting these funds for community outreach and fire-prevention education programs. Ironically, the council has also instructed you to organize and conduct these programs. In every previous year, you have used the entire budget to train and equip your firefighters and to respond to fire emergencies in the city. You know that outreach is important and may indeed help to lower the incidence of fires in the city—assuming, of course, that your city is not rife with arsonists. However, will you now have sufficient resources to accomplish your primary mission? Put another way, is putting out fires or preventing them a better use of your resources?

This fire-fighting/prevention metaphor helps to inform a current and pressing military conundrum. With limited and shrinking budgets, how should the United States balance efforts to prepare for war versus efforts to prevent war? Does the adage “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” hold in this context? We argue it does. America has to find a way to optimize its resources without losing sight of the fact that the primary responsibility of its Armed Forces is to fight and win the Nation’s wars. Theater commands, such as U.S. Pacific Command, are already working on using engagements to create favorable conditions if any actor attempts to challenge its interests in the region.

Sailors work on flight deck as aircraft carrier USS Nimitz, conducting maritime security operations and theater security cooperation efforts, transits Straits of Malacca (U.S. Navy/Derek A. Harkins)

We argue that, first, U.S. political and military leaders must conceptualize Phase Zero operations more broadly than simply shaping the preconflict battle zone; rather, they should think of them as a complex, long-term, grand preventative strategy. Second, military planners should seek indicators for potential leverage points that help senior military leaders make educated, efficient, and effective decisions regarding the use of U.S. assets. These efforts will not prevent every conflict, but they should reduce the number of conflicts and preserve resources for when they are needed most. Such an activity requires a coherent vision that maps out how to move from the present situation toward a desired future environment.

Let us consider a real-world example. In November 2011, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton signaled two noteworthy shifts in U.S. policy. The first was geographic: namely a transition from attention on the Middle East to a stronger focus on the Asia-Pacific region. The second sought to change fundamentally the type of international engagement to which the United States, particularly its Armed Forces, had grown accustomed, a change that reflected a more preventative rather than responsive mentality.1 The decade-long combat operations in Iraq and Afghanistan were showing their first signs of winding down. The American public, reminded of the significant costs of two wars in lives and dollars and struggling with domestic challenges, was growing weary of military and foreign entanglements. Thus, the “Pivot to Asia” required a nuanced approach to promote and protect national interests abroad while at the same time obviating increasing public concern for America’s continual involvement in world affairs.

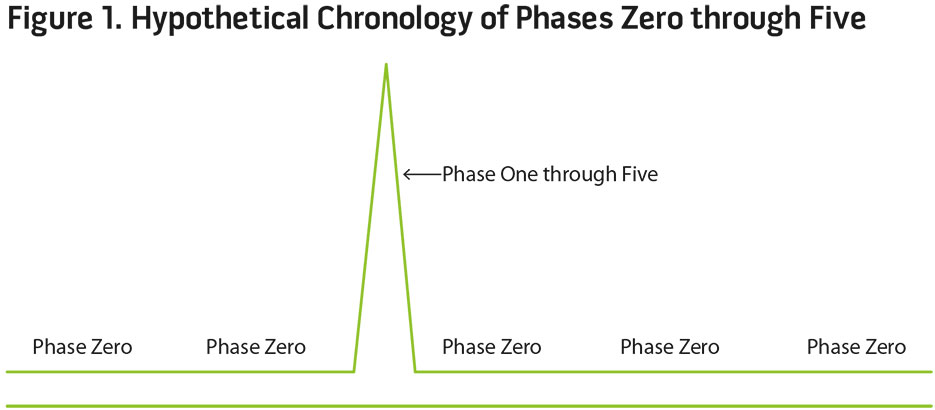

One solution seeks to make military engagement less lethal; U.S. forces should rebalance efforts to focus on dialogue, key leader interaction, building partner capacities and capabilities, encouraging bilateral and multilateral cooperation, and cultivating enduring international norms that support American interests. The U.S. military, however, needs to be careful about when and where it chooses to engage; gains in one place often mean lost ground in another. For example, engagements with India may deepen Indo-U.S. relations, but they hamper U.S. relations with China and Pakistan. It is no surprise that the key to these types of efforts is to make the gains outweigh the losses in the long term. Properly considered, Phase Zero operations should do just that. We must stop considering Phase Zero as a means to prepare for major combat operations (MCOs). Phase Zero operations must become tied to the long-term vision within which short periods of Phases I through V operations occur (see figure 1). Our hope is that such a vision minimizes the likelihood that decisions will be made based on short-term gains with no consideration for potential long-term losses.

Figure 1 depicts a significant oversimplification, but it illustrates the point that Phase Zero operations should be ongoing, with the intent of preventing the frequency and severity of MCOs when they do occur.

Despite even the most successful Phase Zero efforts, MCOs will still be necessary from time to time, so the Armed Forces must remain prepared for those eventualities. If done well, however, Phase Zero operations should support MCOs either directly or indirectly. The problem we are trying to fix is the use of Phase Zero operations to support and prepare for a potential MCO; this kind of thinking potentially undermines the long-term pursuit of an advantageous geopolitical environment in exchange for more short-term objectives.2

Consider a Phase Zero engagement with India. U.S. policymakers consider the Straits of Malacca a potential area of conflict. Cultivating relationships in the region not only allows for a combined effort should conflict become necessary, but also focuses limited resources toward prevention while reserving others for unforeseen circumstances. The change we propose requires a mental shift from a concept of Phase Zero operations that support universal American dominance in every region and theater to one of focusing on efforts that minimize conflict—or, just as importantly, the American role in conflicts—and enable America to retain the resources necessary to ensure dominance in the most vital areas. This means accepting less control globally in exchange for less conflict or less expense in dealing with conflicts in less critical areas should they arise. In other words, Phase Zero operations cultivate relationships in places where we can count on partners for support in areas important, but not necessarily vital, to U.S. national security interests. As a result, Phase Zero operations should help America make more resources available when it chooses the specific places in which it will defend its most important interests. Additionally, Phase Zero operations can potentially decrease the resources required to defend interests in vital locations based on the relationships developed in peripheral areas.

The second part of our argument calls for a modification to operational design when applied to Phase Zero operations. Operational design has the potential to enhance military decisionmaking. As General James Mattis, USMC, declared in 2009, “The complex nature of current and projected challenges requires that commanders routinely integrate careful thinking, creativity, and foresight. Commanders must address each situation on its own terms and in its unique political and strategic context rather than attempting to fit the situation to a preferred template.”3 While we support the use of operational design as the preferred process to help military planners, operational design for Phase Zero should be modified from the template we use for MCO. Using MCO operational design processes can confuse Phase Zero planning because there is a significant difference in focus between planning to implement the use of lethal force and implementing efforts that will avoid or alleviate the need to use lethal force.

In the next section, we explore Phase Zero operations and illustrate how their etymology and process structure are still rooted in an MCO construct and therefore may hamper effective Phase Zero planning. Finally, we offer a modified Phase Zero operational design model for consideration based on the concepts of inflection points and emerging opportunities, a model that has the potential to optimize the conceptualization and planning of this recently articulated military enterprise.

PLAN rear admiral drinks sample of purified water at disaster site in Biang, Brunei Darussalam, as engineers with China, Singapore, and the United States demonstrate water purification capabilities (U.S. Marines/Kasey Peacock)

The Long Game

In 2001, the United States undertook a prodigious military effort to rid the world of dangerous terrorist networks that could operate on a global scale. The enormity of that effort precluded the United States from doing it alone. The 2010 National Security Strategy (NSS) described the need for engagement for the purposes of “combating violent extremism, stopping the proliferation of nuclear weapons, and addressing the challenges of climate change, armed conflict, and pandemic disease.”4 Phase Zero, as defined by General Charles Wald, USAF, was intended to preserve U.S. resources by accomplishing those tasks through engagement rather than through lethal means. The current view articulated in Joint Publication 5–0, Joint Operation Planning, however, undermines this broader perspective of Phase Zero and bounds the idea to shaping operations that support MCO.

Phase Zero operations should focus on building cooperative relationships with states around the world in a way that will enhance continued national security and prosperity. In many cases, military channels offer opportunities to gain access to and build trust between both new and existing partners. Military education, training, and exchanges provide easy opportunities for engagement without the high levels of political scrutiny that often accompany similar opportunities at the diplomatic level. As an added benefit, such activity builds epistemic communities among those at lower levels based on their shared experiences.5 Such advantages can lead to greater influence at higher levels when difficult diplomatic incidents occur (for example, the arrest of an Indian diplomat in December 2013).6 Phase Zero requires a high level of integration between geographic combatant commands and the Country Teams led by each U.S. Ambassador. For many other agencies in the U.S. Government, nonlethal foreign engagement is the primary focus. For example, the United States Agency for International Development states, “The most important thing we can do is prevent conflict in the first place. This is smarter, safer, and less costly than sending in soldiers.”7 For the Department of Defense, however, the majority of effort focuses on organizing, training, and equipping forces to fight and win the country’s wars. Making matters worse, military planning and training for Phase I–V operations compete for resources with Phase Zero requirements. Money spent building relationships and increasing the capacity of others takes away from money available to make U.S. forces more capable. Additionally, the rotation of commanders in the different geographic combatant commands places a premium on short-term investments—those that support emphasis on Phases I–V.

Phase Zero, properly conceived and conducted, requires a long-term investment strategy that transcends successive commanders. The information available and progress achieved during Phase Zero are relatively opaque and ambiguous. Therefore, senior leaders are not going to be able to measure success by any observable—or for that matter, reportable—account over short periods of time. This makes motivating the people doing the Phase Zero mission challenging and increases the difficulty of measuring performance at the highest levels of command. Senior leaders have to adapt from seeking progress-oriented, task-driven constructs, such as operational planning for major combat operations, to open time horizons and outcomes that are fraught with ambiguity. Phase Zero must include considerations and preparations for incongruities between executing planned activities and responding to a potential or actual crisis that would hinder progress toward the desired condition.

Phase Zero should be about preventing conflicts, but it should also be a commitment to cultivating partners and building relationships that enable the United States to achieve and maintain security and prosperity. In a world of growing scarcity, the Nation will have to compromise more to achieve both. The 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review alludes to this quest:

Our sustained attention and engagement will be important in shaping emerging global trends, both positive and negative. Unprecedented levels of global connectedness provide common incentives for international cooperation and shared norms of behavior, and the growing capacity of some regional partners provides an opportunity for countries to play greater and even leading roles in advancing mutual security interests in their respective regions.8

Our concept of Phase Zero operations can enhance American security, but it requires a shift in perspective. The unipolar moment is waning, and the United States must come to grips with a complicated post–Cold War global system that offers rewards to its members more equitably than it did in the last decade of the 20th century. The United States no longer has the means required to influence the global system in a way that makes it the clearly dominant power. This state of affairs is foreign to planning for major combat operations—an endeavor in which there is usually a winner and a loser.

Facilitating Quality Decisionmaking

To stay ahead of the frenetic pace of today’s military commanders, effective staff members use operational design to make sense of the complex operational environment, distill military efforts into categorized segments, and determine nodes that require commanders’ decisions. Ideally, staffs will attempt to predict these decision points and inform the commander of the factors he or she should consider when making those critical decisions. Turnover on military staffs and a lack of continuity among planners, however, have prompted many in the U.S. military to turn operational design into a mechanistic process that essentially requires those involved to “fill in the blanks.” It has produced a culture that unknowingly believes that the process itself, rather than the critical thinking for which operational design was created, is the end product.

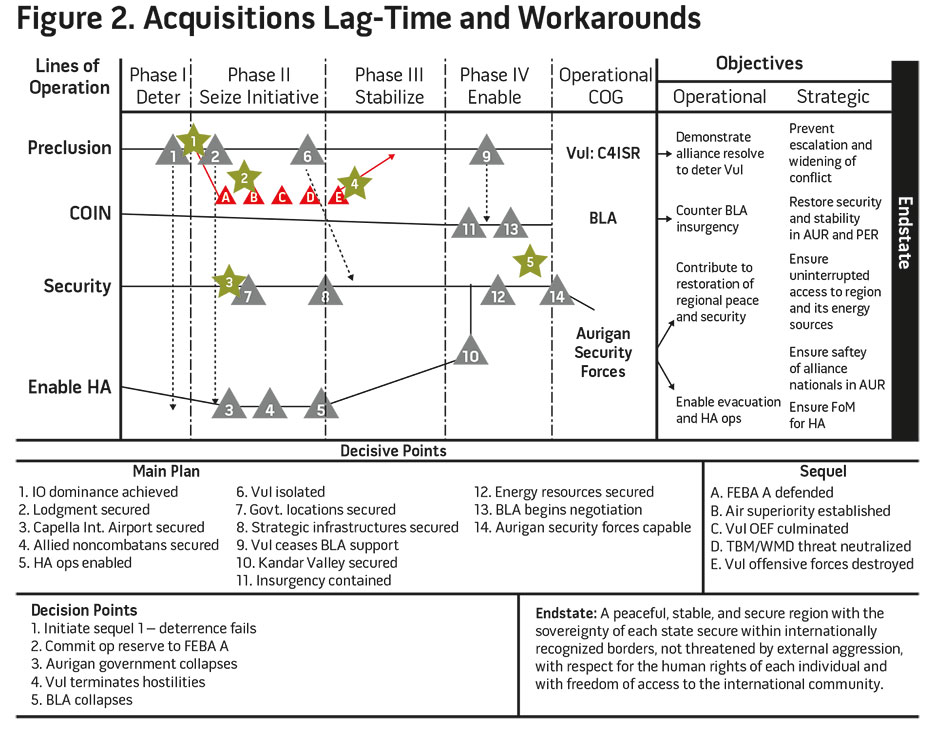

Figure 2 illustrates an example of an operational design product depicting lines of operation.9 The yellow stars indicate decision points where there is an expectation of a commander’s decision; this decision typically either takes advantage of exploited opportunities or rebalances an effort based on changes in the operational environment. In addition to expected shifts or advances in the operational effort, staffs should analyze the operational environment to identify potential emerging situations, so that if they do arise, they may provide advantageous opportunities. Ultimately, operational design is a mechanism that, when properly applied, helps staffs to think about the contextual and temporal complexities of the environment that they are operating in. This awareness enables them to assist their commanders in conceptualizing the environment and overall operation and to make educated decisions about applying limited resources in support of a coherent strategic vision.

This section does not review the details of operational design. Jeffrey Reilly and others have done a fine job of explaining that process, and we wholeheartedly support its more widespread use. Reilly’s model provides a useful and effective method of planning for Phases I through V. But upon examination, it is clear that operational design (as it is currently used) is based on a construct of major combat operations. Three aspects of current operational design highlight this foundation: military end state, center of gravity, and decisive points.

In major combat operations, joint doctrine defines the military endstate as the “set of required conditions that defines achievement of all military objectives.”10 The guidance is unclear as to the best way to define that endstate. But without question, the term itself connotes (and actually denotes) a cessation of military activities: “It normally represents a point in time and/or circumstances beyond which the President does not require the military instrument of national power as the primary means to achieve remaining national objectives.”11 As the analysis in the previous section indicated, no such end point exists in Phase Zero. Rather, the centerpiece of Phase Zero operations is the cultivation of enduring, synergistic relationships.

The term center of gravity finds its origin in Carl von Clausewitz’s seminal 1832 treatise On War: “[One] must keep the dominant characteristics of both belligerents in mind. Out of these characteristics a certain center of gravity develops, the hub of all power and movement, on which everything depends. That is the point against which all our energies should be directed.”12 In MCOs, a commander looks for ways to direct friendly forces in effective ways. Understandably, this is done in an effort to minimize losses and prevent prolonged confrontation. Therefore, the most frequently used rule of thumb is that if you can discover the enemy’s center of gravity and direct your efforts there, you will have the greatest effect. In addition, if you conduct a center of gravity analysis on your own forces, you can better consider defensive posturing.

As Antulio Echevarria explains, however, the U.S. military’s definition of center of gravity has both evolved and diverged over time. The concept should not, in fact, be “applied to every kind of war or operation; if it is, the term may become overused and meaningless or be conflated with political-military objectives.”13 Centers of gravity were the centerpiece of John Warden’s Five-Ring Model, used most famously in the planning of the air campaign in Operation Desert Storm and also in Joe Strange and Richard Iron’s Critical Vulnerability construct, which drills down from centers of gravity to guide the development of actual target sets.14 In Phase Zero operations, however, there is no clearly defined enemy against which commanders can direct their focus. How will a commander know where to place limited resources to have the optimal outcome? Ultimately, a center of gravity analysis for Phase Zero operational designs (at least as it is used today) is problematic.

Joint doctrine posits that a thorough center of gravity analysis will shed light on possible decisive points:

A decisive point is a geographic place, specific key event, critical factor, or function that, when acted upon, allows a commander to gain a marked advantage over an adversary or contributes materially to achieving success. . . . Although decisive points are not COGs [centers of gravity], they are the keys to attacking protected COGs or defending them. Decisive points can be thought of as a way to relate what is “critical” to what is “vulnerable.” Consequently, commanders and their staffs must analyze the operational environment and determine which systems’ nodes or links or key events offer the best opportunity to affect the enemy’s COGs or to gain or maintain the initiative.15

Consider, from the perspective of major combat operations, the logical flow of endstate, center of gravity, and decisive points. What follows is perhaps an oversimplification of the process. But to put it concisely, the military strategist works backward from an endstate to conduct a center of gravity analysis on the enemy, determine critical vulnerabilities that illuminate decisive points, and then (with military planners) group similar decisive points into clearly defined lines of operation or effort. As Keith Dickson writes, “By determining the critical vulnerabilities of the enemy center(s) of gravity, planners have a means to determine decisive points related to attacking those critical vulnerabilities.”16 In MCOs, this seems fairly straightforward. Decisive points are aptly named because they designate where military efforts can concentrate forces to enable mission success. But like endstate and centers of gravity, the term decisive point signifies a finite effort directed at an enemy force within a specified timeframe. Phase Zero efforts are radically different, often open-ended efforts without a defined enemy and without a specified culmination point.

We are not suggesting turning military forces into full-time diplomats, but we firmly acknowledge that the military Services have a large role to play in Phase Zero. To increase effectiveness, planning efforts require a significant shift from current conceptions to allow a more productive relationship between military and other government agencies—especially Country Teams working under their Ambassadors. This effort is put forth with the recognition that the military’s greatest asset is its ability, when called upon, to wage war to meet national objectives and to organize, train, and equip its forces so that its readiness serves as a constant deterrent to would-be aggressors.

Sailors stand watch on bow of Arleigh Burke–class guided-missile destroyer USS McCampbell as ship enters Straits of Malacca in support of security and stability in Indo-Asia-Pacific region (U.S. Navy/Paul Kelly)

During Phase Zero operations, the military still exercises its traditional influence but in a different way and with significantly different political objectives. Thus, the military Services must be much more creative in how they think about and plan these efforts. Creative thinking might be defined as “consciously generating new and useful ideas, and re-evaluating or combining old ideas, to develop new and useful perspectives in order to satisfy a need.”17 But optimizing creative thinking requires a dismantling of framed approaches. As Susan Carter eloquently puts it, “Word choice matters. Sometimes a word skews the whole thread of discussion off track by smuggling in with its connotations a set of ideas that are counter to your own epistemological position.”18 Semantics are important because words have a tendency to feed biases or solidify frames that can stifle creative thinking.

Inflection Points and Emerging Opportunities

Words or phrases such as adversary or decisive points that military planners use in operational design alter the perspective of the planning process. We argue that a shift in focus to two particular terms will significantly change a commander and staff’s view of Phase Zero operations. The first term we suggest is inflection point, which we define as the moment in time when the normal progression of a particular phenomenon significantly changes. For example, India has a reasonably predictable water supply. India’s birth rates and infant mortality rates remain relatively predictable over time as well. At some point in the future, however, India’s population will exceed its water resources. That predictable fact enables a planning staff to identify a logical inflection point.

An inflection point is particularly important in the development of strategy because it identifies a period of such intense change that the actor experiencing the change has not had time to adjust to it. At best, the actor will still be in the early stages of the adaptation phase. It is during this phase that the actor most needs to find some means of adapting to the new situation. An outside actor may be of significant assistance and a helpful influence during this particular period. For example, if you lived in an area with high forest fire potential and learned early in the morning that a forest fire was going to burn your house down at midnight, you would likely resist the efforts of an outsider coming in to assist you in your evacuation. You would have sufficient time to take the necessary safety precautions to gather important documents and valuables and be long gone when the fire took your house. But if you imagine a scenario in which you were in a low fire potential area and you only had 30 minutes of notice, and the same outsider arrived to assist you, would you be more likely to accept help? Perhaps. What if the outsider showed up with a moving van and 20 people to help you get whatever you wanted to take with you? Probably. Finally, what if the outsider and his crew had significant experience with such situations and were willing to offer advice about how to handle the evacuation? Under those conditions, an outsider would be influential, even more so if you had practiced evacuations with the outsider on several previous occasions.

In this example, the inflection point was the shift from the potential for a forest fire to the near certainty that it would occur. Planning staffs should be looking for potential inflection points and align engagements that will position the United States to respond and influence the situation. Inflection points become particularly important because they focus resources in areas with the highest level of influence during a period of shrinking budgets and severely constrained resources. Resources have to be allocated more effectively in the future to enable America to maintain the same level of influence as it had in the past. Inflection points are also important because they represent likely swings in the status quo. For Phase Zero operations, the intent is to prevent these large swings from creating conditions inimical to American interests. Identifying and preparing for inflection points put the United States in a position to stamp out a spark before it becomes a forest fire.

The second term we want to introduce is emerging opportunity. To illustrate the concept, let us refer back to the firefighter analogy and the hypothetical Indian example. Suppose that as the fire chief, your community is faced with an unforeseen drought, which has caused water prices to skyrocket. Coupled with this (and solely for the purpose of this scenario), you worry that there may not be enough fire hydrants in the area to meet your expected response needs. The water shortage and related cost hike are significant enough that many residents have been priced out of filling their backyard swimming pools. But with your access to cheaper water, you initiate a program whereby the fire department fills pools for free on request. The only stipulation is that the residents must agree to give you access to the pool water if needed to assist in fire response. Taken a step further, you could even encourage a program whereby the fire department actually subsidizes construction of more backyard pools in the area. In both of these cases, an unforeseen circumstance—the drought—actually creates an opportunity for increased engagement that may further your long-term interests. Contributing the pool water not only strengthens your connection to the local populace (through the tacit agreement), but also provides a distributed, risk-mitigating resource to assist with your primary firefighting responsibilities should the need arise.

Let us now build on the concept by returning to our hypothetical Phase Zero engagement effort with India. The goals of the effort are to make India a regional leader in international security efforts, while at the same time fostering a bilateral relationship advancing U.S. interests in the region. With little warning, a massive typhoon hits the southern portion of the Andaman Sea, threatening catastrophic destruction to the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, the western coast of southern Thailand, and the northern coast of Indonesia. As the United States has done in similar cases, it redirects military forces to aid (and perhaps even lead) humanitarian relief efforts. Engagement such as this is nothing new. But from a Phase Zero perspective, is it possible that the humanitarian relief might actually create new avenues for interaction with India? The semantics of this point are important. No natural disaster should ever be seen as an opportunity per se, but in the realm of military engagement and relationship cultivation, military leaders and planning staffs should consider how partnerships in unforeseen circumstances can actually further Phase Zero initiatives.

Imagine a scenario in which India and the United States work together to direct a humanitarian airlift to Phuket in western Thailand, which suffered the most devastating damage from the typhoon. Where is the opportunity here? Put simply, the partnership with India in directing airlift aid offers a chance not only to work together toward limited short-term goals (including, obviously, assistance to the victims of the crisis), but also to demonstrate U.S. response techniques in the hope that India takes a larger role in similar regional crises in the future. Ultimately, India might be able to handle such tasks independently (in a way resembling American-style responses). A larger Indian presence in disaster relief in the region might provide area stability consistent with U.S. foreign policy goals and help India to reach its own goals as a rising regional power. It also frees American military resources to respond to crises (or worse, conflict) in areas where the United States does not have similar relationships. This is the cornerstone of Phase Zero engagement.

For planners, unforeseen events are just that: unforeseen. But it does not mean that Phase Zero planning should ignore their possibility (indeed, even their likelihood, given the long-term nature of Phase Zero operations). Any Phase Zero planning should contemplate emerging opportunities that may offer immediate engagement and foster stronger relationships; it must also be flexible enough to re-prioritize efforts accordingly. In addition, similar to the branch and sequel concept of MCO operational design, planners should consider such diversions in terms of their impact on major lines of operation or effort in a Phase Zero construct.

Cavalry scout and Indian army counterpart provide security for fellow soldiers during patrol through forests of Himalayas during exercise Yudh Abhyas (DOD/Mylinda DuRousseau)

Conclusion

A common dictum among military professionals is si vis pacem, para bellum—if you want peace, prepare for war. Strategists and military planners continue to act in a way that places a high emphasis on following this dictum. The United States needs to continue preparing its forces against future threats; we make no argument against that. We argue, however, that preparing for war is an expensive endeavor and that adjustments must be made as resources become increasingly scarce and as other states begin to challenge American dominance in areas that contribute to U.S. and global prosperity. Strategy and planning must become more pragmatic, and spending must focus more on the efficiencies of investing in prevention, rather than paying the enormous costs associated with cures.

Changing the way we think about Phase Zero is a beginning to such an effort. Phase Zero as a means to prevent war is fundamentally different from the current thinking that sees it as a means to prepare for war. If Phase Zero thinking subsumes Phases I through V, it can promote a coherent vision for how to conduct relations and engagements with other states or actors that can contribute to the stability of the global commons and international norms.

Strategists and military planners must concentrate on preventing wars before they start or, at the least, forming strong networks of partners that make defeating troublemakers or would-be adversaries much easier. To that end, the United States must identify key inflection points and emerging opportunities that propel Phase Zero operations in a direction that increases the influence of either the United States or its partners. In some cases, our long-term interest may require putting a partner’s short-term interest first—a notion that America has not had to face since the end of World War II. The United States must become more adept at shaping and nudging actors and conditions rather than relying on its own resources to fix problems. Put another way, it is drought season, and water is getting increasingly scarce. America has to change its thinking to be more effective at preventing fires and at conserving its precious resources so that when they do ignite, its Armed Forces are ready. JFQ

Notes

- Hillary Clinton, “America’s Pacific Century,” Foreign Policy 189 (November 2011), available at <www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2011/10/11/americas_pacific_century>.

- While Phase Zero in our conceptual framework is a global enterprise, combatant commanders will have to make decisions on the prioritization of limited engagement resources.

- General James Mattis, USMC, “Memorandum for U.S. Joint Forces Command: Vision for a Joint Approach to Operational Design,” October 6, 2009, in U.S. Joint Forces Command, Joint Doctrine Series Pamphlet 10, Design in Military Operations—A Primer for Joint Warfighters, September 20, 2010, 2.

- National Security Strategy (Washington, DC: The White House, May 2010), 3.

- For more on epistemic communities, see Peter Haas, “Introduction: Epistemic Communities and International Policy Coordination,” in International Organization 46, no. 1 (Winter 1992).

- On March 31, 2014, the U.S. Ambassador to India, Nancy Powell, resigned after a sharp decline in India-U.S. relations. Many believe that one of the events precipitating this decline was the arrest of Deputy Consul-General Devyani Khobragade in New York City in December 2013 on charges of visa fraud. For more details, see <http://thediplomat.com/2014/04/us-ambassador-to-india-resigns/>.

- For more on the United States Agency for International Development’s mission goals, see <http://www.usaid.gov/what-we-do>.

- Department of Defense, Quadrennial Defense Review 2014 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2014), iii.

- Jeffrey M. Reilly, Operational Design: Distilling Clarity from Complexity for Decisive Action (Montgomery AL: Air University Press, 2012), 78.

- Joint Publication 5-0, Joint Operation Planning (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, August 11, 2011), xxi.

- The Joint Forces Operations and Doctrine Smartbook: Guide to Joint, Multinational and Interagency Operations, 2nd Revised Edition (Lakeland, FL: The Lightning Press, 2009), 3–24.

- Carl von Clausewitz, On War, ed. and trans. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976), 595–596.

- Antulio J. Echevarria II, “Clausewitz’s Center of Gravity: It’s Not What We Thought,” Naval War College Review LVI, no. 1 (Winter 2003), 118.

- John A. Warden III, “The Enemy as a System,” Airpower Journal 9 (Spring 1995), 40–55; Joe Strange and Richard Iron, “Understanding Centers of Gravity and Critical Vulnerabilities,” U.S. Department of the Air Force.

- The Joint Staff Officer’s Guide, Joint Forces Staff College, National Defense University, August 13, 2010, 4–51.

- Keith D. Dickson, “Operational Design: A Methodology for Planners,” Campaigning (Spring 2007), 26.

- School of Advanced Military Studies, Art of Design: Student Text Version 2.0 (Fort Leavenworth, KS: U.S. Army Combined Arms Center, 2010), 63.

- Susan Carter, “Finishing the Thesis: Personal Relationship with Writing,” Wordpress.com, November 9, 2012. Full entry can be found at <http://doctoralwriting.wordpress.com/2012/11/>.