Strategic communication is an important but contested issue, visible in continuing criticisms over the last 5 years. One critique is that the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) definition of the term strategic communication is vague and idiosyncratic in relation to the definitions of other agencies. In turn, this argument runs, the lack of conceptual clarity and of shared, precise terminology hurts the implementation and further development of strategic communication.1 Additional concerns have been raised about the lack of both domestic interagency and foreign partner coordination and cooperation and the absence of credible expertise in strategic communication.2 Still, criticisms point to high-visibility failures in strategic communication—for example, the 2001 “Shared Values” campaign and the 2012 U.S. Presidential response to the “Innocence of Muslims” video—as evidence of both strategic communication conceptual flaws and implementation failures.3

I propose here that strategic communication can be made more conceptually robust and draw on a more powerful and useful suite of tools and methods by borrowing from two language-focused disciplines: rhetoric and discourse analysis. Rhetoric offers an explanatory framework for how and why communication fails or succeeds, as well as practical domain knowledge for how to design and effect sound communication strategies, while discourse analysis is a set of approaches and methods to analyzing real-world language use (discourse). Rhetoric, a humanities discipline centered on argumentation and persuasion, has had practical value and been effective since Aristotle’s time, but it also has an empirical wing developed over the last 60 years. Discourse analysis is a relatively recent offshoot from sociolinguistics, which brings systematic, empirical analysis to language at the micro level and features a wide range of qualitative and quantitative methods.

This issue of which disciplines, and thus which conceptual models, to draw from has high stakes because they imply different practical choices and methods. As a simple example, ask yourself: if you had to convince the authorities that you were not at place X at Y time, and if you had to convince them you were sincere, how would you do it? From an empirical perspective in discourse analysis, the answer would depend on the discourse conventions of the authorities. If American English speakers were asking you, then brevity, concision, and coming straight to the point might be convincing. However, if Arabic speakers were your audience, repeatedly proclaiming your innocence might be the right strategy. Most importantly in this example, those strategies are opposed—strategies suited for one discourse and culture would likely fail for the other.

Pentagon Press Secretary Rear Admiral John Kirby answers questions for media during weekly press conference, October 2014 (DOD/Glenn Fawcett)

Below are two illustrative case studies that show both the conceptual power of rhetoric and discourse analysis and also the nuts-and-bolts methods for analyzing communication and communication failures. For these examples to make the most sense and provide context, I first briefly sketch out how rhetoric and discourse analysis conceptually differ from our current iteration of strategic communication. I then recommend how DOD in general and the combatant commands in particular could effectively and efficiently operationalize insights and methods from these disciplines.

Strategic communication as it currently stands draws primarily from communications theory, public relations, and marketing. In this model, communication is understood to be primarily monologic (from a speaker to an audience) and dependent on the ability of the speaker to manipulate or tailor language to properly craft and deliver the right message to persuade or change opinions of the audience. This model also implicitly borrows from linguistic theories popularized by Noam Chomsky that treat language as having a preexisting structure that good speakers use to their advantage. It is from such a model that a ubiquitous phrase such as “controlling the narrative” can have currency and be in circulation.

The above conceptual model is significantly different from much contemporary theory in linguistics and sociolinguistics. In more contemporary theory, communication is dialogic: everyone is talking to everyone else, all the time. Even when there is a single speaker at a given moment, such as a formal speech or delivery of a single author paper, all kinds of other talk are implicated (intertextually): prior speeches and writing, public talk in the news or private talk in the streets, and expected responses. This means that text and talk are more like conversations than messages. In place of linguistic code to be manipulated, we enter into a conversation with a set of dynamically evolving conventions and expectations that provide current structure.

Instead of thinking about strategic communication as manipulating code (and thus manipulating an audience/outcome), contemporary linguistic science offers us a model of partners in dialogue and argument, working interactively and iteratively to accomplish practical ends. Even when these partners in dialogue have diametrically opposed goals and their interactions are hostile, they are still interactive and social. This model is inherently reflective because to be good at it, we need to have as much understanding of and insight into our own communication practices as we do into those of our enemies and partners. Instead of trying to control the narrative, the goal is to artfully and effectively enter into conversation—a subtle difference that has profound implications for practice.

To illustrate the range of concepts and methods that we could borrow from rhetoric and discourse analysis and then apply to strategic communication, I offer two widely separated and disparate case studies. They include both quantitative and qualitative approaches, using computational and human means, for both international and domestic problems, at the macro and micro scales of analysis.

Linguistic Smuggling in Taliban Information Operations

Taliban strategic communication makes use of the rhetorical device “linguistic smuggling” as a tactic in opposing the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF). Their public statements appear to focus on technical details to which ISAF is most likely to react, disguising what the author(s) consider a more important point to Afghan audiences: defining ISAF as crusaders and invaders. As a result, ISAF’s responses likely will not credibly satisfy Afghans.

As an illustrative example, consider how Taliban propaganda and an ISAF press release treat the same green-on-blue incident. Below is a two-part rhetorical analysis of a Taliban press release, coded to show linguistic smuggling (hiding a contestable claim) and an argument stasis (sticking point of contention):

The casualties of the CRUSADE INVADERS: As “a handful is a specimen of the heap” and the evidence is that the CRUSADE INVADERS have always tried habitually to conceal their casualties. Let us have a look on the incident of the Jalraiz district of Maidan-Wardak province which took place on Monday 11th March. In this incident, an infiltrated Mujahid who was performing his duty among the Arbakis, turned the barrel of his gun to the CRUSADE INVADERS and opened fire. Consequently 22 soldiers were killed and a number of them were severely wounded but the enemy acknowledged only 2 casualties.4

The above sample text shows a Taliban communications tactic: linguistic smuggling. Advertisers in the West frequently use this to divert attention away from contestable claims, attempting to get consumers to accept embedded assumptions. Linguistic smuggling works through our expectations for given/new information, by moving new (and therefore contestable) information from its conventional position after established given information. In the sentence “These condos are luxurious,” we can think of the condos as the topic (what the statement is about) and the claim of luxury as the comment (commentary on that topic). But if we say, “These luxury condos are available for only a short time,” the claim of luxury has been smuggled from the comment into the topic.

In the above Taliban example, the author(s) tactic does not rely on how many ISAF members were killed but rather on defining ISAF as anti-Islamic invaders in the vein of the Crusades. The tactic is to covertly smuggle the claim of ISAF as “crusade invaders” into sentence topics, as if it were given information. However, instead of countering/anticipating such definitions, and perhaps proposing an alternate definition of ISAF as defenders of the legitimate Islamic government of Afghanistan, ISAF offers only the factual details. The ISAF press release for the same incident reads: “Two U.S. forces-Afghanistan service members died in eastern Afghanistan today when an individual wearing an Afghan National Security Forces uniform turned a weapon on U.S. and Afghan forces.”5

This press release reflects current DOD best practices in strategic communication: clarity, openness, and honesty.6 This corresponds to American ideas of “straight talk” and implicitly trades on two kinds of proofs (modes of persuasion). One is logos-dependent—trying to arrange the facts of the case in a way that supports our position. The other is ethos (credibility), which has three components: practical wisdom, goodwill, and virtue. Straight talk aims to demonstrate virtue. The whole approach is very American: get the facts straight, and do it with consistent honesty to develop credibility.

While I want to temper my claim here—there is not a body of good empirical data verifying Afghan public discourse and argument conventions—the Taliban tactic is more plausible, on the terms of Afghans, than the U.S.-style ISAF tactic. The facts and figures of any given incident may not be all that important: whether 2 or 20 ISAF members died in the attack may be immaterial. What more likely matters in Afghan discourse—the center of gravity here—is ISAF’s definition as either a crusade invader or a legitimate defender of Islam. Taliban authors such as those in the above example clearly understand this principle; ISAF strategic communicators may not.

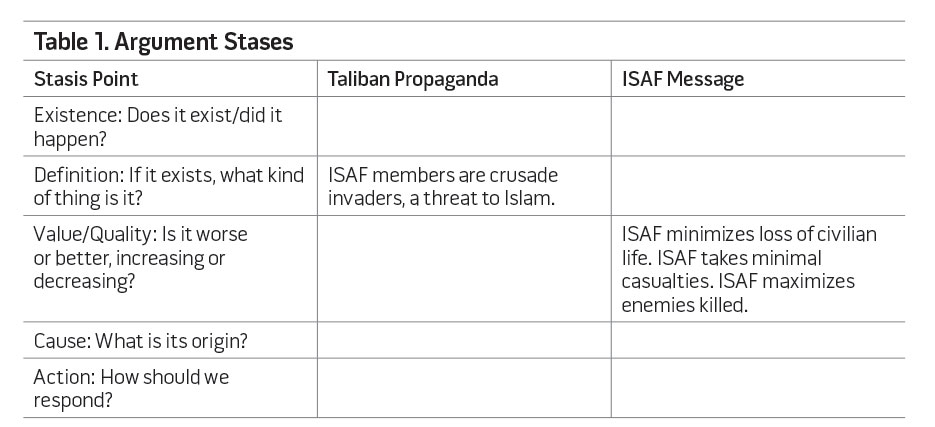

In this sense, such Taliban propaganda writers and ISAF are talking past each other, at different segments of argument. In rhetorical theory, these segments are stases, literally “sticking points” in argument. The five major stases can be used to diagram speakers talking past each other (see table 1).

Neither side disputes the first possible stasis point—the existence and relevance of ISAF. But through linguistic smuggling, the Taliban writers have found covert (and very plausible) ways to argue the second stasis point, which ISAF does not explicitly address. This is critical because stases are progressive—we cannot successfully work on later stases until we have worked through prior ones. Since ISAF misses that the stasis point in play is the definitional stasis, they cannot argue the last one: the action stasis. If ISAF are legitimate defenders of an Islamic Republic, then they should be supported, or at least not opposed. But if they are “crusade invaders,” Afghans have a moral obligation to resist.

The stases also have an ethos dimension. The ISAF/American-style response tries to gain credibility through virtue (honesty), which helps build up our ethos. But so does another part of ethos: eunoia—goodwill to the audience. “Crusade invaders” do not bear goodwill, and consistency in talk does not change that. Telling people we hope to persuade (or leaving unchallenged the belief) that we are indeed an invading foe, dedicated to a crusade against them, but that we are honest invaders, is a questionable communications strategy.

A Computer-Aided Rhetorical Analysis of U.S. Marine Corps Public Speech

When U.S. Marine Corps general officers speak on the record in public, they have a distinctive linguistic style that communicates their stance: one of moral and knowledge certainty. They perform this style consistently, regardless of how contested an issue is and to whom they speak. This may be a constraint on their ability to speak effectively in civil-military deliberations.

This second case study is a domestic example using corpus analysis software to empirically describe large amounts of textual data. In this case, corpus analysis software is used to quantify style: the linguistic micro-choices we make in representing the world. Small but consistent choices in language aggregate to offer the audience a perspective on what is being talked about. For example, a leader in an organization who uses “I” regularly versus “we,” or says “I know” rather than “I think,” is offering very different rhetorical experiences to his or her audience. When journalists consistently describe the object of their reporting with phrases such as “tries to,” “makes an attempt to,” and “appears to be,” they are hedging—offering small but critical linguistic markers to their audience that they should not trust the surface presentation of the object.

Corpus analysis software designed to count these micro-style choices across a range of categories allows for statistical tests on the results in order to make empirical claims about what is happening in communication, and to make visible trends and differences that an analyst could not see because of human limits to memory and attention.7 In this sense, corpus analysis software acts like a prosthetic for human communication analysts, and can both empirically support or disprove human qualitative impressions and bring a bird’s-eye view to the kind of data we usually use human reading to analyze, but in mass quantities no human could ever address. Through the following domestic communication case, I want to show how an empirically grounded discourse analysis method can help speakers from one group (in this case, senior Marine Corps officers) be more self-aware in their communications with another group (civilians) and thus be more effective.

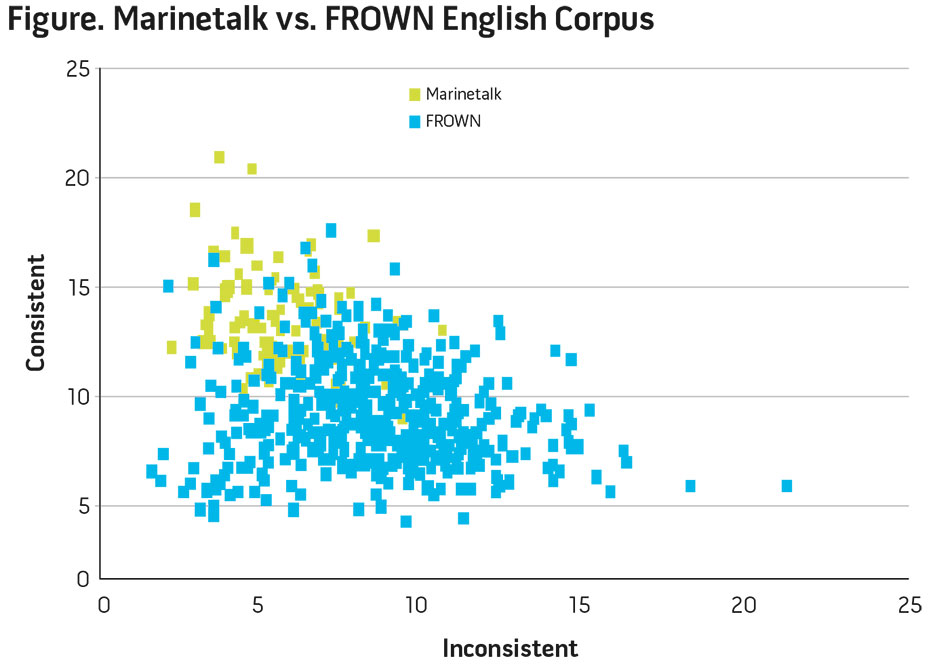

Figure 1 is a graphical representation of how distinctive Marine Corps public speech is—a style I call Marinetalk. This is the speech of Marine senior officers speaking in 2010 referenced against general contemporary English, which shows a tight, distinctive cluster.8

The terms Consistent and Inconsistent on the Y and X axes refer to how consistently present, and thus characteristic, a given stylistic feature is relative to general English. The graph uses a nonparametric statistical test that allows two data sets to be compared for the regularity of distribution of features.9 Thus, the farther up and to the left a data point is, the more strongly the text aligns with Marinetalk, while data points lower and to the right are the least like Marine public speech.

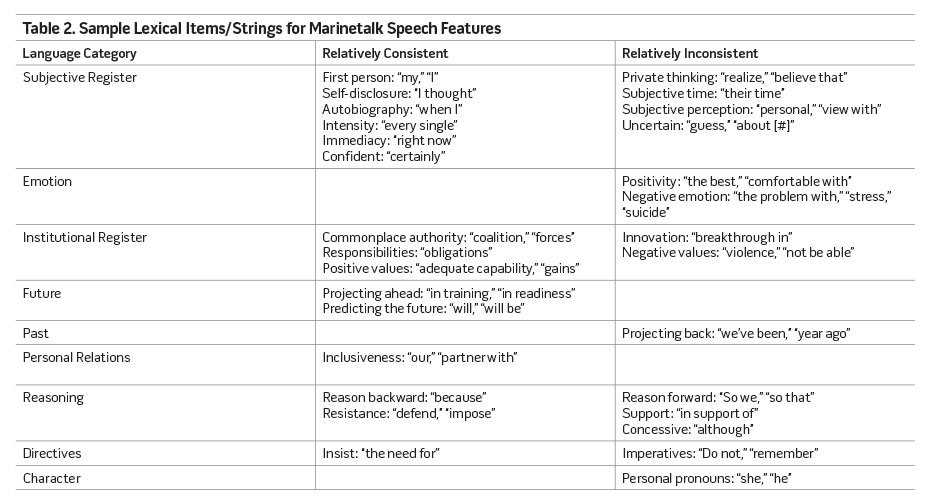

Table 2 illustrates some of the relevant characteristic style features of Marinetalk when compared to general English, with example word strings. Essentially, Marinetalk sounds like a highly confident/certain person telling others about a shared future, invoking positive reasons why they should buy into it. This will likely not surprise anyone who has been a Marine or has worked with the Service. What does seem surprising, and needs explanation, is the consistency of this way of talking.

The rhetorical profile detailed above makes sense given the mission and structure of the Marine Corps. The institution needs to motivate large groups of people to coordinate their actions to arrive at desired endstates/places. Marinetalk reflects institutional needs to speak with certainty (which includes subjective register speech from personal authority and confidence, and directive insistence), argue constructively for future goals, index positive values both as means and end, and promote cohesion with positive/inclusive values.

The consistent style Marine general officers use indexes their attitudinal stances toward their audience and topic, how sure they are, and so forth. This is something that emerges cumulatively in talk, not through any specific, discrete element; their style offers a particular rhetorical experience to others through linguistic choices as they speak. In this case, Marines use lexical and grammatical choices to sound certain, speak from experience, and create a “we” in a shared future.10 The certainty that marks Marinetalk puts Marines on a superior footing as duty experts on military subjects. This works well most of the time—in uncontested issues, the Marine senior officer speech analyzed in this study received collegial questioning, thanks, and praise.

But in contested issues such as ending “Don’t Ask/Don’t Tell” (DADT), Marine speakers received a much more challenging reception, including cross-examination, critiques, and counters to their claims. Given the contested subject and the opposition of audience members, Marinetalk seems to function as a constraint on Marines’ testimony before Congress. How Marines spoke is not the only issue, of course. The content of the argument and political positions of other participants are relevant as well. However, this only highlights the choice not to vary speech by situation and context—talking to a civilian audience as if they were a Marine audience on important and contentious issues such as ending DADT does not make sense.

Just as in the ISAF example, Marine senior officers tend to repeat the most fundamental structural patterns of their discourse. These Marines are smart people and are no doubt aware of many surface features of language they need to vary by audience—not using acronyms or insider technical terms is an obvious one. Borrowing from discourse analysis and methods such as corpus analysis and computer-aided rhetorical analysis could add high-precision visibility over their stylistic choices, strongly leveraging their ability to communicate effectively with civilian audiences.

Implications and Recommendations

Borrowing from these language-focused disciplines has important implications at multiple levels for both policymakers and commanders. Some possible directions include the following.

Incorporate Discursive Strategies to Language Translations. Translation into another language is not enough by itself; it is very possible to speak another language while repeating our own culture’s discursive strategies. The sincerity and trustworthiness issue mentioned earlier is a good example. In Arabic discourse, repetition is an incredibly important proof of sincerity and a principle linguistic strategy in argument. In Arabic discourse, repetition operates at the level of both content and structure. To be persuasive in argument, Arabic speakers might repeat their point over and over again (content), but they might also do so rhythmically, repeating parallel sentences or phrasing (structure). This conflicts with Western, particularly American, ideas of sincerity, which rely in part on brevity and the construction of a trustworthy ethos of virtue.

Our enemies understand this; consider the English and Arabic suicide message videos of Hammam Khalid Al-Balawi, responsible for the 2009 bombing of Forward Operating Base Chapman in Afghanistan. Both have roughly the same content, but their discursive strategies differ greatly. The Arabic version relies heavily on rhythm and repetition, an appropriate argument strategy for an Arabic speaking audience. By contrast, in the English version the author(s) establish the moral virtue of the bomber through ethos proofs in a prelude (or proemion), a standard feature of Western rhetoric. The Arabic version also features plural pronouns exclusively, while the English version includes sections with singular pronouns, again reflecting microlevel understanding of Arabic and English discourse conventions and argument strategies. The author(s) of those messages knew not only to translate into the right languages but also to adopt matching discursive strategies.

Turn the Culture and Language Lens on Ourselves. Critical analysis of how others in the world speak and live is essential to U.S. operations overseas, from the tactical to the strategic levels of war. The Services recognize this and have their own iterations of culturally/linguistically grounded education and training (for example, the Army Culture and Foreign Language Management Office and Marine Corps Center for Advanced Operational Culture Learning). This is good; however, we need to understand our own culture and the cultural aspects of our own language just as much as we need to understand the language and culture of our partners and enemies. Cultivating a self-aware and reflective posture in which we habitually interrogate our own discursive and rhetorical practices would put us in position to use such insights skillfully when we talk to the world.

Draw and Adapt from Language-Focused Disciplines. There is an existing body of theory, research, and methods from discourse analysis and rhetorical studies that DOD can leverage. To adapt this mature field to a novel application, the Services and DOD will need to operationalize a scholarly body of study. This is something the U.S. defense establishment has experience doing, and it is well positioned to develop relevant partnerships with academia. This could follow three lines of effort.

Adapt concepts and methods. Strategic communication can benefit from empirically derived concepts for thinking through roles in communication, issues of identity and relatedness in communication, problems in argument, and so on. The argument stases analysis in the Taliban messaging case study is a good example of a conceptual starting place for thinking through ends and means in persuasion. There is also a significant body of technical methods available to apply. These cover the macro and micro ends of communication and an incredibly wide range of analytical entry points to communication: dimensions of explicitness and implication in discourse, ideological aspects of discourse, clause-level resources for values and appraisals, and so on.

Adapt existing off-the-shelf technology. The corpus analysis of Marine speech is a good example of a powerful and precise method for leveraging human analytical attention in communication and has great potential for atmospheric monitoring—analyzing thousands of responses across traditional and social media to U.S. communications or gaining insight into communication norms and practices in other language communities could be invaluable. The existence of reliable, robust technology for doing this in English means that adapting to target languages is plausible and could be done cost effectively.

Employ professionals in language-focused disciplines. In the last 10 years of warfare, the U.S. military learned to draw on the expertise of professionals in culture-focused disciplines such as anthropology. While there is criticism of specifics of the Human Terrain System, the program springs from recognition that population-centric operations require expertise in cultural knowledge. Language is just as fundamental to human behavior as culture is, and tapping the human capital of professionals in this area can be a powerful tool for informing strategic communication.

Make Combatant Commands the Point of Insertion. As the entities best situated regionally to communicate in audience-appropriate ways and because of their functional needs, combatant commands are the logical point of insertion for revisioned strategic communication. We can envision empirical data collection and both quantitative and qualitative analyses to establish baselines and variances for regional responses and interpretations of combatant command messaging. This in turn could provide invaluable data-driven and timely feedback and insight for improved communication that is effective for regional and local audiences.

A More Effective, Empirically Grounded Strategic Communication

We have not abandoned strategic communication because we have an intuitive understanding that it matters. But we have not been satisfied with it either, casting about for ways to fix strategic communication (or its application). This article is a starting point for thinking through an improved understanding of strategic communication and better practice. I have tried to make a case for language disciplines such as discourse analysis and rhetoric as mature bodies of knowledge with powerful explanatory theory behind them, a wealth of expert knowledge built up over approximately a century of rigorous empirical fieldwork in natural settings, and highly precise and reliable methods for analysis and production of communication. By moving to an evidence-based understanding of how discourse and communications actually work, we can engage with and communicate more effectively with the rest of the world. JFQ

Notes

- Dennis M. Murphy, “The Trouble with Strategic Communication(s),” Army War College Center for Strategic Leadership Issue Paper 2-08, Carlisle Barracks, PA, 2008; Christopher Paul, “‘Strategic Communication’ Is Vague: Say What You Mean,” Joint Force Quarterly 56 (1st Quarter 2010), 10; Patrik Steiger, “Virtuous Influence: An Imperative to Solve U.S. Strategic Communication Quandary,” Army War College Center for Strategic Leadership, Carlisle Barracks, PA, March 24, 2011.

- James G. Stavridis, “Strategic Communication and National Security,” Joint Force Quarterly 46 (3rd Quarter 2007), 4.

- Steve Tatham, U.S. Governmental Information Operations and Strategic Communications: A Discredited Tool or User Failure? Implications for Future Conflict (Carlisle Barracks, PA: U.S. Army War College Press, 2013).

- “Afghanistan in the Month of March 2013,” Ansar Al-Mujahideen, April 19, 2013, accessed at <www.ansar1.info/showthread.php?t=45578&goto=newpost>.

- “U.S. Forces–Afghanistan Casualty Report,” March 11, 2013, available at <www.isaf.nato.int/article/isaf-releases/u.s.-forces-afghanistan-casualties.html>.

- Stavridis, 4.

- The software used in this analysis has a highly granular taxonomy of language that includes 15 categories at the highest level down to 119 at the finest level of granularity. Some examples of top-level categories include emotion, personal relationships, reasoning, and future/past talk.

- Data included 34 public on-the-record speeches from 13 senior Marine officers in 2010, primarily congressional testimony, but also press question and answer sessions, town hall meetings, and ceremonial speeches, reflecting representative considerations such as population, size, and generalizability. This also meant a judgment that 2010 was a representative year in that civil-military talk that year covered everything from ordinary, course of business concerns (for example, enlisted professional education) to contentious, unusual concerns (such as ending Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell).

- Boot-strap Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, a nonparametric test used to see if and how the distribution of a feature in the Marinetalk corpus varies from the comparison FROWN corpus (a standard national corpus of general American English, spoken and written).

- For a detailed analysis, see William M. Marcellino, “Talk Like a Marine: USMC Linguistic Acculturation and Civil-Military Argument,” Discourse Studies 16, no. 3 (June 2014), 385–405.