ABSTRACT

Civilian participants in conflagrations are rightly concerned about cultural property protection (CPP) in host or occupied nations and appeal to military players to see preservation of icons as a force multiplier. Present precautionary measures are neither empowered nor timely enough to prevent unnecessary damage. An independent international academic center is proposed that would join a military CPP competence center fashioned by NATO or an academic entity to validate and energize projects. The concept of military necessity must be examined by all military and civilian stakeholders with CPP remaining depoliticized and kept in accord with international agreements and mandates. Related controversies can be mitigated through education, training, resource commitment, and dialogue, all creating a cooperative civil-military culture that protects cultural treasures.

In June 2009, the United States ratified the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict (the 1954 Hague Convention). This makes government protection of cultural property mandatory. Recent conflicts in Iraq, Egypt, Libya, Mali, and Syria have triggered renewed interest in Cultural Property Protection (CPP). The obligations of CPP are included in international treaties and military regulations and complicated by various stakeholders with different levels of understanding and willingness to invest in training and application.

Because CPP includes a military responsibility to limit damage, it should be implemented before kinetic operations begin. Lack of CPP planning can exacerbate social disorder; eradicate national, ethnic, and religious identities; elicit international condemnation; and prolong conflict. If planned and executed correctly, CPP can be a force multiplier by concurrently contributing to international and domestic stability and goodwill. From this perspective, suggestions for general protection procedures and methods for implementing them against further disruption and damage are appropriate.

Historical Trends and Current Conditions

The vulnerability of cultural property to damage because of armed conflict is not new. Examples include the destruction of Carthage (149–146 BCE) and of the Ancient Library of Alexandria (48 BCE). A plethora of modern examples indicate that conflict-related destruction and looting of cultural property continue. Incidents from World War II are numerous and include the destruction of the famous Monte Cassino Abbey in Italy and damage to cultural property during the high intensity bombing of Germany.

During the current Syrian conflict, the shelling of national heritage sites including the Crusader fortress Krak des Chevaliers, as well as citadels, mosques, temples, and tombs, has been reported.1 Whether these are wanton acts of destruction, collateral damage, or iconoclasm is unclear.

Repatriation ceremony including nine colonial paintings, monstrance, and four pre-Columbian objects marks return of collection of cultural property, art, and antiquities looted from Peru; pictured: Saint Rose of Lima painting (ICE/Paul Caffrey)

In Mali, various United Nations (UN) Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Sites, which include mosques and mausoleums, were damaged or demolished in 2012 by the designated foreign terrorist organization Ansar Al-Din (Defenders of the Faith), which considers the shrines idolatrous. Several of the esteemed Timbuktu manuscripts consisting of scholarly works and letters from the 13th century have also fallen victim to the Malian conflict. (Further research has found that only some of the manuscripts were destroyed.) Perpetrators and their intentions have been numerous and varied, and heritage crimes have been widespread. International Criminal Court (ICC) Chief Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda asserts, “those responsible could face prosecution as their actions constitute a war crime.” This is important; crimes committed during conflict can be prosecuted by the ICC based on individual criminal responsibility. The U.S. Senate has not ratified the Rome Statute of 1998 of the ICC. Mali is a state party to The Hague Convention of 1954 and its First Protocol; however, the National Movement for the Liberation of Azwad, which occupied northern Mali in 2012, is not internationally recognized and is therefore not under the jurisdiction of this convention.

Military Involvement

Military involvement in CPP should be viewed through the lenses of two international legal instruments: the 1998 Rome Statute of the ICC and the 1954 Hague Convention for Protection of Cultural Property. In the current hybrid “four-block war” operational environment, where military forces engage in all conflict phases, circumstances involving heritage protection must be recognized and analyzed in their complexity to mitigate and hopefully prevent damage to national and regional cultural heritage and identities connected with such heritage.

Established legal instruments that hold both individuals and parties responsible for heritage crimes sometimes do not extend to all perpetrators. For instance, Mali is a State Party to The Hague Convention of 1954 and its First Protocol, but the extremist group that seized power in northern Mali at the time is not an internationally recognized party, so it does not classify as a State Party. This implies that the extremists cannot be prosecuted for the destruction of cultural property as an official party but there is room for individual criminal responsibility. Unfortunately, although The Hague Convention’s Second Protocol mentions individual criminal responsibility in chapter 4, this provision cannot be applied because Mali has not signed it.

However, the 1998 ICC Rome Statute, which constitutes a landmark treaty on individual responsibility in international crimes, contains important provisions for crimes against cultural property. The ICC can prosecute individuals responsible for deliberate destruction, and Mali is a party to the Rome Statute. It should be noted that these legal instruments only complement the national legislations of affiliated State Parties; they do not override them. For instance, when criminal laws in a given State Party to the ICC Statute cannot be enforced, the statute can function as a substitute. It states, “Nations agree that criminals should normally be brought to justice by national institutions. But in times of conflict, whether internal or international, such national institutions are often either unwilling or unable to act.”2

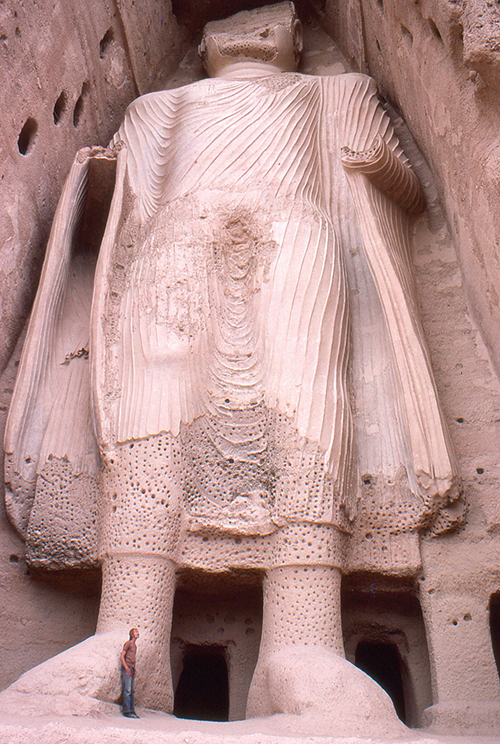

Two relevant sections in ICC’s Article 8 describe locations and buildings classified as religious or historical monuments, such as the Timbuktu mosques and tombs, which cannot be deliberately attacked unless they are turned into military objectives. This implies that those who intentionally undertake acts of violence against objects of cultural heritage have committed war crimes. Again, the Rome Statute recognizes individual criminal responsibility; although countries in which the crimes take place normally have national legislation to prosecute them. The Mali case and the earlier case of the Taliban’s destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas, both because of supposed idolatry, support the idea that cultural property is vulnerable to political manipulation.3 In Mali this was evidenced by Ansar Al-Din’s accusation that UNESCO was prejudiced against it and acted in favor of the transitional government.

Prevention and Responses

Addressing problems such as iconoclasm requires not only an awareness of cultural heritage and history but also effective legislation followed by appropriate actions. One possible action is the establishment of an international military and civilian cultural emergency response team. Considering recent cultural property devastations, we can reasonably conclude that military organizations do not take sufficient preventive measures. However, the U.S. military is currently meeting this challenge. Several cultural resources working groups of civilian experts and military stakeholders are in place to monitor ongoing military operations for compliance.

Groups active in these endeavors include the Combatant Command Cultural Heritage Action Group (CCHAG), International Military Cultural Resources Working Group (IMCuRWG), which is now coordinated with North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) Joint Analysis Lessons Learned Center, and U.S. Africa Command, among others.

Planning and Implementing

In the four-block war, troops operate during all phases of a conflict, frequently in circumstances where civil experts and local police cannot function. They are often the first to arrive at the conflict area and have logistical assets to operate in “cultural emergencies.” At these times, forces must comply with national and international laws, but protecting cultural property is also a tactical and strategic objective and ensures military deliverables, such as force multipliers.

Failure to provide protection can make the situation problematic. Coalition forces failed to protect the National Museum of Iraq from looters during the fall of Baghdad in 2003. The ensuing negative public ramifications caused diminishment of force acceptance by the Iraqi people and anger from Western media about the war’s progress. On the other hand, NATO received positive press for precision airstrikes during Operation Unified Protector, an effort aimed at protecting cultural property facilitated by CPP Lists (CPPLs) that resulted in better strategic communications. Military organizations, specifically ground tactical units, while not sufficiently trained for CPP and not typically working with specially designated CPP officers, understand archaeologist Laurie W. Rush’s caution: “Deployed personnel in unfamiliar environments must realize that members of local communities are the ones who should assign value to cultural properties in their landscape.”4 In other words, research must be done, and local experts or reachback capabilities must be consulted or used before determining what is perceived as cultural heritage in an area of responsibility.

As demonstrated in Mali, however, conflict or postconflict situations can be so intense that ascertaining the exact condition of important cultural property is difficult or impossible. This is currently the case in Afghanistan, Egypt, Libya, Mali, and Syria. Attempts have been made, however, to establish assessment mechanisms for conflict regions. Although Blue Shield and IMCuRWG provided a good example by sending small assessment teams to Egypt and Libya, the international community did not follow through with these types of initiatives. Organizations such as UNESCO and NATO have presented various outlines for a systematic institutionalized approach as well as designs for overarching governing institutions. These include suggestions for international military cultural experts, who among other things should draft procedures and plans for civil handover capacities.5

However, these initiatives appear to remain in embryonic stages, having never had follow-through, purportedly because of lack of funding. As a result, the international community may have responded too late to save Syria’s cultural heritage. Reported damage to cultural property there varies from shelling, army occupation, terrorism, looting, and uncontrolled demolition that looks similar to Al Hatra in Iraq, where demolitions damaged the ancient temples. World Heritage Sites such as the ancient villages of northern Syria, Krakdes Chevaliers, and cultural properties in Damascus, Aleppo, and Palmyra are examples of damaged heritage. Added to this type of devastation are smuggling, theft, and the repurposing of strategically located cultural sites such as citadels, towers, and castles.

Numerous contemporary conflicts take place in identified archaeological source countries. Many are developing states that must concentrate on internal economic matters and that lack the financial means to manage their cultural resources and protect them from domestic or international abuse. Local politics influenced by personal advantage also complicate this situation.

Recent Developments

New developments associated with the rapidly evolving hybrid warfare environment include three-dimensional virtual reconstruction, geographic information systems, and satellite remote-sensing used in the assessment of sites, objects, and monuments. When more information becomes available about potential cultural resources, the process of clearly identifying “cultural heritage” becomes more complicated. Moreover, the status and nature of what falls under cultural heritage is subject to change. Examples are cultural landscapes—the process of memorializing the past and creating places of memory (or lieux de memoires), or “traumascapes,” such as New York City’s “Ground Zero,” and other types of heritage including traditions or living expressions passed down through oral transmission, the performing arts, social practices, rituals, and traditional skills.6 Just as The Hague Convention protects tangible heritage, the 2003 UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage protects these. This development in classifications also affects the sensitivity of cultural heritage topics in media and communications: negative media coverage of the Bush administration’s lack of protection for the Baghdad Museum made tepid international support for the Iraq War almost disappear. Internet and social media sensitize national and international constituencies to the vulnerabilities of both tangible and intangible assets even further.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement repatriate gold artifacts and ancient vase, discovered by special agents to be destined for New York business suspected of dealing in looted cultural property, to Afghanistan government (ICE/Paul Caffrey)

Dilemmas and Oppositions

Unfortunately, interested parties often find themselves pitted against each other when attempting to safeguard cultural property in compliance with international humanitarian law. Varying stakeholders and assessors of value further complicate the process. A typical cause of this behavior among cultural experts is lack of financial resources and insufficient training. Other stresses arise from varying organizational structures or lack of embedding possibilities, jurisdictions, kinds of expertise, and spheres of influence. Taking a unifying role in articulating these resources might be advantageous to operations as the military assesses, plans, and implements CPP in compliance with various national and international treaties and organizations.

Several types of clashes of interests and responsibilities can be distinguished:

- military experts versus civilian specialists and nongovernmental organizations

- dual roles in the military consciousness: fighter/destroyer and preserver/protector

- differences in culture, terminology, and operational practice between U.S. and foreign forces

- differences between the academic heritage discourse and technical, religious, military, and political discussions including desired outcomes.

Research on implementing CPP shows that disagreements remain. Examples are the occasional clashes between air and land operations and antagonisms caused by cultural differences among the respective military cultures. The ideal situation is to provide targeting experts with accurate CPPLs before operations begin and to use technology and military expertise to adjust targeting plans with cultural heritage assessment reconnaissance from civilian experts. An example of a good practice is the case of Ra’s Al Marqab during the conflict in Libya.

Lessons of Ra’s Al Marqab

Unrest began in Libya in March 2011, swiftly developing into a full-fledged conflict. The fighting initially included bombardments and shelling from warring parties. Air strikes followed and the United States and its coalition partners established a no-fly zone, which transitioned into a NATO operation. Libya is a party to the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property and signed its First (1957) and Second Protocol (2001).

The country has five World Heritage Sites designated by UNESCO: the Greek archaeological sites of Cyrene, the Roman ruins of Leptis Magna, the Phoenician port of Sabratha, the rock-art sites of the Acacus Mountains, and the old town of Ghadamès. Numerous archaeological and historical sites dating from prehistoric times to World War II, and important to Mediterranean history are located on the Libyan coast.

On June 14, 2011, UNESCO contacted all parties to ensure the protection of Ghadamès and its immediate surroundings and appealed to them not to expose Leptis Magna to damage. The U.S. National Committee of the Blue Shield began gathering information in March 2011. Later, the U.S. Government partnered with Oberlin College, New York University, as well as with other institutions and organizations including various national Committees of the Blue Shield. A draft CPPL was sent to the Special Assistant to the U.S. Army Judge Advocate General for Law of War Matters and Air Combat Command. The CCHAG disseminated information to several parties through the U.S. Air Force/Air Combat Command. The Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at New York University collated and reduplicated data and helped prepare the list submitted to the Department of Defense (DOD).

The Libya CPPL was provided to DOD prior to the initiation of the no-fly zone, then the International Committee of the Blue Shield was brought into the process. IMCuRWG shared approximately 200 coordinates with NATO’s Allied Command Transformation (ACT) in Norfolk, Virginia. Through different routes, the United Kingdom (UK) Ministry of Defence (MOD) had been provided all the information given to the United States. Experts from the UK’s Society for Libyan Studies, King’s College, and the Rural Planning Group added valuable data. The list was forwarded to the UK Joint Staff, which forwarded it to targeteers. IMCuRWG also passed the coordinates to operational staff of the Royal Netherlands Armed Forces. The Netherlands, in accordance with UN Security Council Resolution 1973, took part under NATO command in imposing a no-fly zone over Libya. Forwarding the CPPL data to appropriate offices was crucial since the information could be entered into targeting databases and shared with NATO. UNESCO became involved after the bombing began on March 19, 2011. Civilian CPP networks established a working relationship, and future CPPLs were entered into the system on short notice, taking into account legal and ethical considerations based on established professional rules and practice.

Muammar Qadhafi’s forces had placed a radar station on a hilltop where Ra’s Al Marqab, a small Roman fort, lies near Leptis Magna, overlooking the city of Al Khums. The radar station was protected by five antiaircraft guns placed next to the Roman walls. A multidisciplinary cultural emergency assessment team from Blue Shield and IMCuRWG visited the location on September 29, 2011, and found heaps of metal rubbish. All weapons and support equipment had been destroyed by NATO airstrikes using the collateral damage estimation methodology and precision targeting.7

The team inspected the Roman walls and the vaults next to the guns and found few visible signs of the attack except for small surface scratches caused by shrapnel. There were no cracks or fallen stones. For the local archaeologists accompanying the team, this was their first visit to the site due to restrictions from the former regime.

Ra’s Al Marqab serves as an example of precision bombardments that limit damage to cultural property and demonstrates the importance of providing exact coordinates to, in this case, NATO planners. However, we should recognize the challenges. During a civil-military panel discussion at an American Institute of Archaeology Conference held in Philadelphia, military participants emphasized the importance of setting priorities to avoid an overwhelming number of listed site coordinates, thus giving commanders a better opportunity to make decisions based purely on military grounds when necessary.8

CPP experts must understand DOD or MOD targeting procedures such as the collateral damage estimation methodology, which accounts for “no strike” items protected from military action and considers aspects of weapon effects and mitigation options to minimize potential damage to those items. Cooperation with military planners provides the possibility of exploiting advanced technologies, such as satellite remote-sensing and geographic information systems. By engaging in such cooperation, cultural specialists can supply risk preparedness and preventive conservation notes for inclusion in geospatial data sets for military planners.

It is relevant for military organizations to gain knowledge of CPP, including the role of cultural heritage aspects as part of the original causes of conflicts and associated identity perception mechanisms. Even newly constructed cultural identities can become political tools in the hands of regimes; for example, the German National Socialists attempted to recreate a past and rationale through manipulated use of borrowed iconography and monumental, intimidating architecture. On the other hand, Robert Bevan reiterates that a useful strategy to defeat a foe is to “exterminate this enemy by obliterating its culture,” and by culture he means “identity.”9 The scope of such destruction can be relatively wide when, for instance, the danger to common objects, especially buildings, is also considered a threat to the group’s identity, collective memory, and overall consciousness, as is the case with “urbicide,” a concept used during the Bosnian wars in response to widespread and deliberate attempts at destruction of urban life and its material resources.10

This leads to the more comprehensive idea of places of memory, including traumascapes, that can be considered containers of identity. This level of refinement enlarges the gap between civil and military heritage expertise, increasing the need for research, dialogue, and transfer of knowledge between civilian and military spheres. Because of the subject’s sensitivity, there is an urgent need for further research on the military perspective, including legal implications. Academic analysis of these heritage and identity issues is creating an extensive body of literature that addresses multiple factors against the continuously changing background of CPP. It could be argued that such analysis is undertaken from perspectives more advanced than any existing heritage debate addressing solely military aspects, thus enlarging a conceptual gap between civilian and military viewpoints.

An Example of Good Practice

In December 2011, the Austrian MOD, in cooperation with NATO’s ACT and IMCuRWG, organized the first NATO-affiliated course on CPP in accordance with the 1954 Hague Convention and NATO’s Standardization Agreement 1741 for Environmental Protection. NATO stated that “lessons identified from recent operations indicate that NATO’s CPP capability remains suboptimal and is insufficient to fully achieve the aim of The 1954 Hague Convention.” Through operations in the Balkans, Afghanistan, and Libya, NATO concluded that specific actions are required to promote a deeper understanding of the legal and identity-related issues associated with CPP. Practical implementation is also needed to strengthen site protection to prevent looting and to work with locals to improve their CPP capabilities.

During the last decade, the Austrian MOD organized several courses and seminars on CPP that included international military and civilian participants, with some sessions involving NATO. The Austrian MOD is among the few military institutions that conduct training based on the 1954 Hague Convention, specifically concerning the articles on dissemination, training, and education. It has also made serious efforts to introduce CPP and its military perspective into the international scientific discourse. The 2011 workshop discussed the practice of military planning and the conditions, limitations, and possibilities for CPP officers that exist in the planning process in the Austrian armed forces.

The discussion revealed many problems and impediments as well as opportunities for participation, not only in Austria but also internationally during NATO- or UN-led operations. Participants took part in a planning exercise to experience practical problems. New case studies based on recent conflicts were introduced while legal experts examined them. The event showed the need for continued education, dialogue, and international cooperation. Unfortunately, no new initiatives have been introduced by NATO since then.

Joint Strategies and International Cooperation

It seems clear that international cooperation in establishing military compliance with CPP obligations is necessary. In most cases, financial and personnel resources from individual countries are insufficient to achieve a comprehensive solution. The development of educational tools will be possible by combining forces, thus providing cost-efficient training, interagency cooperation, nonduplicative research, academic education, and in-theater assessments. The benefits are synergistic and timely implementation, which is important given the current conflicts where cultural heritage is at risk and efficiency in securing it is at a low level. Overall, CPP can generate important force multipliers and help end military missions sooner while contributing to post-conflict reconstruction by stimulating tourism and strengthening national identities.

Policymakers are gradually becoming aware of two important factors in the assessment and study of international CPP cooperation. First, cooperation brings efficiency; second, it enhances cultural diplomacy, loosely defined as “the exchange of ideas, information, art, and other aspects of culture among nations and their peoples in order to foster mutual understanding.”11 CPP as part of cultural diplomacy also provides the means to restore old contacts or develop new ones after conflict with countries that have opposing ideologies. “Cultural diplomacy is the first resort of kings,” states former cultural diplomat Richard Arndt.12 Cultural diplomacy policy will not be taken seriously if the implementing country has a reputation of destroying cultural property during military operations or is seen to avoid legal obligations as formulated by The Hague Convention of 1954. Furthermore, the apparent disregard of international agreements can precipitate “lawfare,” or continuous time-consuming, resource-intensive legal battles that stand in the way of a multitude of desired outcomes.

We still must be cautious. Eric Nemeth suggests a potential for proactive protection of cultural artifacts, particularly in light of the 2009 U.S. ratification of The Hague Convention of 1954. He claims U.S. foreign policy can transform the risk related to the potential loss of cultural property into a diplomatic gain by insisting that military interventions include a strategy for securing cultural sites and avoiding collateral damage.13 This approach is mandatory under international humanitarian law; however, Nemeth does not mention that Washington has yet to ratify Protocols 1 and 2 of The Hague Convention of 1954. This means that using this treaty to promote certain ethically driven values could backfire when it will be stressed that the United States evokes a treaty for which they do not carry full responsibility.

Smaller Bamiyan Buddha from base, Afghanistan 1977, destroyed by Taliban in 2001 (Phecda109)

Nevertheless, The Hague Convention of 1954 and, if applicable, its protocols should be used in strategic communication and cultural diplomacy, albeit only by the parties who fully endorse them. Unfortunately, if demonstrable success in implementing the convention is the condition for its use, not many states or parties would qualify. Therefore, promoting CPP for diplomatic or economic reasons is a valid and potentially beneficial idea that should be addressed cautiously.

The Link Between Cultural and Natural Resources

Successful appeals to military organizations to implement The Hague Convention of 1954 and its protocols have been difficult, even though the advantages seem obvious. To begin, terms such as culture, cultural heritage, cultural affairs, cultural awareness, cultural property, cultural identity, and cultural diplomacy are vague and do not suggest any relationship between culture and the natural environment as has been established in newer concepts such as cultural landscapes. The terms heritage and property present both legal and material aspects. In the legal sense, cultural heritage is often referred to as cultural property, in which case cultural heritage should be seen as a special case under the general term cultural property. Cultural properties in danger of damage or destruction during modern asymmetrical conflicts are often owned and maintained by states, so using terms such as property and heritage can unnecessarily imply or emphasize a disputed or claimed ownership. However, at least one undisputed common denominator persists: cultural property is a resource, or what sociologist Pierre Bourdieu identifies as cultural capital. Therefore, the term cultural resources may be the best option.14

An extra advantage is that the term resource is normally associated with “natural” resources. This notion opens the door to a new approach to CPP that involves natural resources while tackling the problem of the lack of military organizational structures necessary to house CPP capabilities. Institutional embedding on shorter notice while waiting for permanent CPP dedicated positions to be created is important in the light of today’s cultural heritage disasters related to armed conflict.

Military units must contend with environmental issues, and military personnel are accustomed to handling resources with care. Legal instruments and regulations such as NATO Standard Agreement 1741 directly address members on issues of natural and cultural resources. Others are congressional legislation that established the Legacy Resource Management Program and the U.S. Central Command Contingency Environmental Guidance Regulation R-200-2. Not only is the connection between cultural and natural resources addressed in these measures, but there are also indications of possible mitigation and initiative, which suggest that the protection of cultural property could be taken into account early in the military planning process.

Further examples of cultural heritage–related environmental problems caused by military activities are soil pollution, which can contaminate or destroy cultural artifacts, and soil replacement and supplementation, such as unintentional damage inflicted by forces using Hercules Engineering Solutions Consortium barriers. Culture-environment connections are only beginning to be codified into military regulations and doctrines, although direct results should become apparent soon. Consequently, CPP will automatically be considered in military plans, and a judicious combination of CPP and military planning should bring desired improvements. Recently, U.S. Africa Command included a CPP annex in its theater campaign plan that outlines the international standards all personnel should follow.

Balancing Interests

The relationship between CPP and security is complex and dynamic. In today’s world, which is complicated by local religious and cultural identities as well as the possibilities of unethical affiliations with various agencies, we must not forget the ability for insurgent groups to generate profits from cultural objects via illicit trafficking.

Another vital aspect of CPP is that the status and definition of cultural heritage is subject to change. Examples are the Soviet statues of Lenin and Stalin that were no longer considered to be cultural heritage after the disintegration of the Soviet Union. Meanings shift constantly, and apart from being preserved, sites are often redesigned to contemporary perceptions, indicating that many sites no longer constitute the presence of the past but rather the present presented as the past. Local regulations are only as permanent as shifting and dynamic language allows them to be. Military operations must somehow adapt to them.

Conclusion

Civilian participants tend to sentimentalize and politicize the protection of cultural heritage. The subject is so sensitive that the military has been compelled to take into account both past and present circumstances before implementing a cultural heritage strategy. We can see CPP as a form of preventive conservation. As stated by the National Gallery of Australia:

Preventive conservation aims to minimize deterioration and damage to artworks, therefore avoiding the need for invasive conservation treatment and ensuring protection for now and the future. Preventive conservation is based on the concept that deterioration and damage to works of art can be substantially reduced by controlling some of the major causes of this in the gallery environment.15

If we replace “works of art” with “cultural resources” and “gallery environment” with “the environment,” we have a workable definition for CPP purposes and the beginnings of an orchestrated approach to the challenge. Five observations and four recommendations follow:

- Military success can no longer be defined by tactical successes alone but in terms of post-conflict political, social, economic, and cultural stability of the nations and groups involved. CPP is a force multiplier. It should not be regarded as an unnecessary burden that is legally imposed but militarily problematic.

- CPP touches on the issue of general “cultural awareness” but requires unique specialized skills beyond those necessary for “general cultural awareness.”

- Current measures to prevent conflict-related damage to cultural properties are neither suitably extensive nor adequately quick to prevent damage.

- An independent international academic center that would work with a military CPP competence center, organized by NATO or a military academic institute, would provide efficiencies and authority to various projects.

- Lawfare, a more subtle form of warfare and an unintentional byproduct of a real or potential breach of The Hague Convention of 1954 protocols, could divert or consume governmental resources.

- We should approach military necessity in the context of CPP and discuss and encourage its study among all stakeholders, both military and civilian.

- Both civilian and military experts must study and debate the relationship and possible connections of CPP with global security.

- CPP must be depoliticized as far as possible and ensure compliance with international agreements and mandates.

- Because the United States ratified The Hague Convention of 1954, it should appropriate sustainable resources to fund training and implementation to ensure DOD compliance.

Cultural property protection depends on a significant attempt to create a military or cooperative civil-military cultural emergency assessment capability, which at the very least is able to monitor and mitigate cultural destruction during conflicts. The complexity of cultural property definitions and the practicalities of its protection have created many controversies, but these are resolved with adequate education, training, resource development, and dialogue among all stakeholders. JFQ

Notes

- See Emma Cunliffe, Damage to the Soul: Syria’s Cultural Heritage in Conflict (Palo Alto, CA: Global Heritage Fund, 2012), available at <http://ghn.globalheritagefund.com/uploads/documents/document_2107.pdf>.

- For further discussion of individual responsibility, see Mirielle Hector, “Enhancing Individual Criminal Responsibility for Offences Involving Cultural Property—The Road to Rome Statute and the 1999 Second Protocol,” in Protecting Cultural Property in Armed Conflict: An Insight into the 1999 Second Protocol to The Hague Convention of 1954 for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, International Humanitarian Law Series, ed. Nout van Woudenberg and Liesbeth Lijnzaad (Leiden, Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2010).

- Joris D. Kila, Heritage Under Siege: Military Implementation of Cultural Property Protection Following the 1954 Hague Convention (Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2012).

- Laurie W. Rush, “Cultural Property Protection as a Force Multiplier in Stability Operations,” Military Reviewno. 2 (March–April 2012), 36–43.

- For suggestions, see Joris D. Kila, “Utilizing Military Cultural Experts in Times of War and Peace: An Introduction,” in Culture and International Law, ed. Paul Meerts (The Hague: Hague Academic, 2008); Joris D. Kila, “Cultural Property Protection in the Context of Military Operations: The Case of Uruk, Iraq,” Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 13, no. 4 (November 2011), 311–333.

- See Pierre Nora, Les Lieux De Memoire, Bibliotheque Illustrée Des Histoires (Paris: Gallimard, 1984); and Maria Tumarkin, Traumascapes: The Power and Fate of Places Transformed by Tragedy (Victoria: Melbourne University Press), 2005.

- Hafed Walda, Ph.D., at King’s College; Joris Kila, Ph.D., at University of Vienna; and Karl von Habsburg.

- For a brief overview of these meetings, see the Archaeological Institute of America’s online report titled “The Cultural Heritage by AIA-Military Panel Conference,” available at <http://aiamilitarypanel.org/events/champ-workshop-at-2012-aia-annual-meeting/cultural-heritage-information/>.

- Robert Bevan, The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War (London: Reaktion, 2006).

- Martin Coward, Urbicide: The Politics of Urban Destruction (London: Routledge, 2009).

- Milton C. Cummings, Cultural Diplomacy and the United States Government: A Survey (Washington, DC: Center for Arts and Culture, 2003).

- Richard T. Arndt, The First Resort of Kings: Cultural Diplomacy in the Twentieth Century (Washington, DC: Potomac Books, Inc., 2005).

- Erik Nemeth, “Repatriating Part of Saddam Statue Could Promote Democracy,” Chicago Tribune, June 7, 2012, available at <http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2012-06-07/opinion/ct-perspec-0607-artifacts-20120607_1_hiram-bingham-iii-artifactscollateral-damage>.

- Pierre Bourdieu and Jean Claude Passeron, The Inheritors: French Students and Their Relation to Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979).

- National Gallery of Australia, “Collection Conservation: Preventive Conservation,” June 16, 2012, available at <http://nga.gov.au/conservation/prevention/index.cfm>.