DOWNLOAD PDF

Andreas Kuersten is a third-year law student

at the University of Pennsylvania Law School.

He has interned with both the U.S. Navy and

the U.S. Air Force Judge Advocate General’s

Corps and is currently with the Air Force’s Civil

Litigation Division.

For years, the issue of sexual assault in the U.S. military has fallen under constant scrutiny. Nonprofit organizations, Senators, and countless others have directed criticism to both the prevalence of sexual assault within the military and the measures taken to address it. The attention is certainly warranted; not only is sexual assault a serious crime with significant ramifications, but it is also a direct threat to national security by disrupting the unity and discipline of the Armed Forces. However, the increased condemnation of the military appears to miss what should be the overall goal and potential of this movement and the military’s intimate involvement: civil-military cooperation toward society-wide sexual assault prevention.

The military offers a unique and ideal environment for social and legal experimentation—not haphazard trial and error, but true academic research and implementation. The Armed Forces have directly and indirectly served this purpose in the past. Pertinent examples include desegregation and homosexual integration. America’s military ranks and legal system are centrally controlled and relatively immune to the pressures of elected politics. They can implement policy much more quickly and efficiently than civilian society. In addition, military leadership has the ability to withstand failed but well-researched and reasoned endeavors. Moreover, the military climate strongly favors action and is conducive to immediate steps to stem the tide of sexual assault across the branches.

In beginning this analysis, however, it makes sense to take a step back and examine the criticisms often aimed at the Armed Forces when it comes to sexual assault, and how they have skirted around and diverted attention from the overall goal this article puts forth. Three of the most prominent attacks leveled against the Armed Forces, directly and indirectly, are that the military is a more disciplined section of society with a unique sexual assault problem and should therefore be held to a higher standard in handling it; the increase in reported sexual assault evidences the military’s failure to adequately do so; and this failure can be largely attributed to military law.

Airman serves as Victim Advocate at Community Violence Intervention Center at Grand Forks Air Force Base (U.S. Air Force/Susan L. Davis)

A Higher Standard

Critics frequently assert that the military should do more, yet they fail to cite comparable civilian situations. There is often an implicit argument that the military should be held to a higher standard than civil society in tackling sexual assault. While this proposition is accurate, it is true for specific reasons that often go unmentioned.

It is often implied, and stated outright by the military itself,1 that the Armed Forces should be held to a higher standard because it is a more controlled and disciplined section of society. Certainly, each branch presents itself as a builder of better people. Through the rigor of training, Soldiers, Marines, Sailors, and Airmen are taught, among other things, the virtues of honor, discipline, loyalty, and respect. All these values are grossly inconsistent with acts of sexual assault. But military service is not a bubble where, upon entry, individuals are stripped of every prior societal influence and never again intermix with outside communities. As Micah Zenko and Amelia Mae Wolf point out, recruits have lived at least 17 years before exposure to the military lifestyle and continue to be members of civilian society afterward.2

Sadly, however, most sexual assaults occur where the direct strictures of military command hierarchy fail to reach. They are committed in homes, dormitories, bars, and numerous other environments, and alcohol and other substances are often involved. Despite the reach of official military training, values, and discipline, they have proved unable to have their desired effect because society in general also has a sexual assault problem that exerts great influence on Servicemembers. Critics who fail to note this and hold the Armed Forces to a higher standard under the implication that sexual assault is a military problem are ignoring a key impediment to Pentagon efforts. Sexual assault is an epidemic that plagues all corners of society, and the military, it turns out, is not exempt.

Studies on sexual assault in civil society often disagree, but they all generally point to its pervasiveness. The Department of Justice (DOJ) found that sexual assault only occurred at a rate of 0.9 victims per 1,000 people in 2011.3 Conversely, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, found a year prior that in a 12-month period, 5.6 percent of women suffered sexual violence other than rape, 1.1 percent suffered actual or attempted rape, and 5.3 percent of men suffered sexual violence other than rape. (Data were not available on the percentage of men who suffered actual or attempted rape during the period because the incidences were too few.4) Both studies excluded those in military barracks but did not bar other Active-duty Servicemembers. But with these individuals making up only 0.4 percent of the population, this is largely irrelevant.5

Chief of Staff of the Army General Raymond T. Odierno speaks during Service’s official recognition of Sexual Assault Awareness Month at Pentagon, March 2014 (U.S. Army/Alfredo Barraza)

While both studies have their strengths and weaknesses, the CDC report appears more accurate. Unlike the CDC study, the DOJ analysis is not focused on sexual assault; rather, it analyzes criminal victimization in general. Zenko and Wolf have also noted that the CDC study employs metrics far more similar to those in comparable studies aimed at the military. Furthermore, the DOJ itself has previously noted the weakness in its rape and sexual assault analytic methods.6 Yet even a percentage lying somewhere between the two studies means millions of Americans suffer some form of sexual assault every year.

Studies of specific civilian segments of the population reveal more disheartening data. A 2000 study titled “The Sexual Victimization of College Women” estimated that 4.9 percent of female university students suffered rape or attempted rape during the calendar year and 15.5 percent were sexually victimized in some way during the academic year.7 A 2007 study on rape by the Medical University of South Carolina’s National Crime Victims Research and Treatment Center estimated that 5.2 percent of college women suffered rape that year, excluding attempted rape and sexual assault.8

Thus, the military’s inability to fix the problem of sexual assault in its ranks is likely, at least in part, a reflection of the military’s intimate connection to the broader community where the issue also remains pervasive. This becomes most apparent when comparing the situation in civilian colleges to that in the Armed Forces, as Rosa Brooks did in Foreign Policy.9 Seventy-three percent of military victims are ranks E-1 to E-4—in other words, junior grade enlisted members whose ages, living situations, and behavior align with those of college students.10

No matter the effort, discipline, or hierarchical structure, the military will never be able to completely tackle the issue of sexual assault on its own. That is not to say it should not try, and it should be held to a higher standard in protecting and educating those in uniform and others. But this higher standard should be advocated for reasons other than the military being more disciplined or sexual assault being a uniquely military problem. Rather, the standard should be higher because of the damaging impact sexual assault has on America’s fighting forces and therefore national security—and also because, as this article concludes, the military offers America’s best chance at making real and lasting progress in the battle against sexual assault.

The discipline and structure of the military are, however, an effective critique of the poor results the Armed Forces have had in confronting the problem. In theory, this structure should enable the issue to be addressed swiftly. So how has the military been doing?

Increasing Numbers

Pentagon research estimates that 26,000 military members were sexually assaulted in 2012,11 compared to 19,000 in 2010.12 It further states that 3,374 sexual assaults were reported in 2012—an increase over the 3,192 in 2011,13 3,158 in 2010, and 3,230 in 2009.14 The Department of Defense (DOD) also estimates that 6.1 percent of women and 1.2 percent of men in the military experienced sexual assault in 2012, up from 2010 when the respective numbers were 4.4 percent and 0.9 percent.

At first glance, this trend appears troubling. How can it be that with all of the publicity and condemnation directed at the military and the new programs developed to prevent sexual assault, the problem has actually gotten worse? Perhaps there are additional routes one can take with this data.

First, there are issues with these findings. Aside from likely being “unrealistically high,”15 the study arriving at the estimated figure of 26,000 Servicemembers having been sexually assaulted is underinclusive, but perhaps simultaneously overinclusive in terms of its application to the military. It is underinclusive in that it does not consider results from civilians who have suffered sexual assault at the hands of Servicemembers. Military members are not the only victims of sexual assaults perpetrated by those in the Armed Forces, and civilians should be included in studies addressing the Pentagon’s handling of the issue. The estimate may be overinclusive in that it does not identify the perpetrators of the assaults. Servicemembers suffer these crimes at the hands of those outside of the military as well as those within, as the data make clear. Yet the Armed Forces have far less power and influence over those outside of their command structure who might harm Servicemembers.

Regardless of how these alterations to any future study might adjust the data, the finding that the number of sexual assault victims and reports is rising is not necessarily entirely negative. Increasing reports of sexual assault and self-identification by victims of such crimes can also be considered initial positive steps in this fight. The military has devoted considerable attention and resources to taking on this issue, starting numerous programs to address prevention and offering both legal and nonlegal victim support.16

There are several examples of what the military is doing. First, there is the creation of restricted reporting.17 Many victims of sexual assault are wary of reporting the crime to authorities. This has been especially highlighted in the case of the military where a 2012 Pentagon study estimated that only 11 percent of sexual assaults were reported that year.18 The predominant reasons among female victims were not wishing anyone to know, feeling uncomfortable making a report, not believing the report would be confidential, and fearing social and professional retaliation. Restricted reporting seeks to address this by allowing victims access to medical care, advocacy, and victim services without notifying the command or automatically initiating a criminal investigation. These restricted reports are filed, and victims maintain the option of making them unrestricted if they change their minds. Individuals have the opportunity to get care and assess their legal situations before opening their experiences to criminal procedure.

Second, the Sexual Assault Response Coordinator (SARC) program was created.19 Out of this came the unit-embedded SARC position, whose training is now standardized through the Sexual Assault Advocate Certification Program.20 These specially trained individuals exist solely to assist victims of sexual assault confidentially in almost every fashion. They attend to the individual’s needs and ensure victims know of and can access all the resources available.

Third, the Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Office (SAPRO) was created in 2005.21 SAPRO serves as the centralized authority for addressing sexual assault in the military. This unification of projects and programs under one office serves to standardize the military’s response to sexual assault across branches and provides a dedicated source of training and research. An example is Sexual Assault Awareness and Prevention Training, which is now a continuous and frequent requirement across the Armed Forces.

Fourth, Sexual Assault Awareness Month has created an annual period of even more intense sexual assault awareness.22 Sexual Assault Awareness and Prevention Month has been a staple of April for years within the military. During this time, all branches additionally promote sexual assault awareness and conduct training events.

Fifth, the Air Force has spearheaded the Special Victims Counsel (SVC) program,23 which was embarked on in January 2013. SVCs are lawyers whose sole function is to attend to the legal needs of victims of sexual assault. These victims may contact SVCs and receive personal legal assistance while their restricted reports remain confidential. Within 48 hours of contacting the SVC office, an individual will receive a response and representation. Preliminary results from the program appear positive. Approximately 300 Airmen were assisted from its inception to May 22, 2013. Twelve of the 22 victims who received SVC representation and filed restricted reports changed them to unrestricted reports so criminal procedures could commence. This 55 percent conversion rate is substantially above the 17 percent rate for the military as a whole in 2012.24 Additionally, 95 percent of the victims who received SVC assistance stated that their counsel advocated effectively on their behalf and helped them better understand the process.25 These results have led Representatives Tim Ryan (D-OH) and Kay Granger (R-TX) to introduce legislation mandating that the Pentagon expand the SVC program to the entire military.26

The highlighting of these actions is not meant as a pat on the back for the Armed Forces. Rather, they show a possible additional or alternative explanation for the sexual assault data emanating from DOD. These programs have significantly raised awareness of sexual assault within the Armed Forces, educated Servicemembers on these crimes, and encouraged and helped victims to come forth. With only an estimated 11 percent of sexual assaults reported, these increases should be expected from the programs the military has put in place. The desired results of these endeavors are consistent with the rising reports of sexual assault and self-identification by victims and therefore are possibly ripe for replication in the civilian world.

Nevertheless, there has clearly been an increase in reported sexual assaults and therefore increased pressure on the military legal system. How has the military been handling this increased pressure, and sexual assault in general?

The Military Legal System

In most respects, the challenges the military justice system faces in dealing with sexual assault are the same as those facing civilian systems. These cases are notoriously difficult because they often involve drugs or alcohol, few witnesses (usually only the parties involved), victims reluctant to cooperate, and lack of evidence. All this clouds the central issues—that is, proving the presence or lack of consent and the capacity to consent in the first place. Furthermore, many cases are not the types people typically envision when they hear the charge of sexual assault. They often do not involve strangers attacking individuals and physically compelling them to engage in sexual acts. A large number occur between parties who know one another and are both intoxicated, under circumstances where consent is an issue, and involve coercion that is not as clear as a stranger jumping out of the shadows and attacking. These situations still cause great harm to victims, but they are much harder to prosecute.

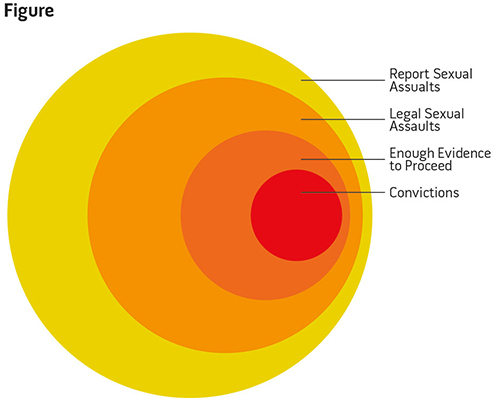

The universal problem facing the prosecution of sexual assault can be illustrated through a tiered analysis (see figure). When getting to the final number of sexual assault convictions, one starts with every interaction that is reported as sexual assault. This number is whittled down to those that could actually be classified as sexual assault under the law. The number is further diminished to cases where there is enough evidence to prosecute and/or the victim cooperates. The final number of sexual assault convictions is arrived at after these cases have been adjudicated, with the perpetrators found guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. Ultimately, as Captain Lindsay Rodman, USMC, notes, “The inability to obtain a conviction in many of these cases is not the fault of the commander, prosecutor, or military justice system. Rather, it is a problem of expectation and misunderstanding about the capabilities of a criminal justice system.”27

These troubles are made vivid in a recent study of military adjudication and conviction rates for sexual assault.28 In response to strong criticism over low prosecution rates, from 2009 to 2010 the military increased its prosecution of sexual assault cases by 70 percent. Yet these prosecutions only resulted in a 27 percent conviction rate compared to the 90 percent conviction rate for all crimes. The military has always arguably prosecuted cases that would not have been prosecuted in civilian court, but this is now being explicitly shown by the numbers. Where civilian courts refuse to move forward because a case is “unwinnable,”29 the military is pressing ahead.

This is troubling for three reasons. First, cases are going forth that may amount to “show trials.” They might simply be prosecuted so the military can appease critics who want action. When these prosecutions end in acquittals, an arguably more severe hit to the military justice system occurs as victims lose faith in it and critics use these results as ammunition. The Armed Forces are stuck between a rock and a hard place and, as Rodman puts it:

By seeking to prosecute anyone accused of sexual assault without understanding the source of the underlying problem, leaders are actually contributing to the same cycle of acquittals they seek to avoid. Criminal prosecution is not the answer to resolving many of these reports. Overprosecution only perpetuates the problem because convictions are simply not achievable in many of these cases.30

Second, military prosecutors are being forced to go after lesser charges in cases where they know they will not secure a conviction for sexual assault but are pressured into court. This has resulted in alleged rapes being prosecuted as adultery. Matt Collins noted that this leads to less satisfaction for a victim, who sees the accused escape with a misdemeanor, insufficient punishment, or pressure to plead guilty to adultery to avoid more severe charges.31 Justice is not served.

Third, the low conviction rate could lessen the likelihood that victims will report sexual assaults. They may see a legal system that cannot provide them with justice and avoid engaging with it. This, in turn, may leave more offenders unpunished or embolden them to victimize others.

Having noted the military legal system’s possible influence on sexual assault reporting and incident rates, it now makes sense to address the elephant in the room: commander control of the military legal system. As it stands, in contrast to civilian legal systems, commanders—not prosecutors—make the ultimate decision of whether a case goes to trial in the Armed Forces, and if the ruling and conviction are approved.

Critics of the military justice system have used this fact to attack it as outdated and tipped in favor of the accused, and to call for the removal of commander control.32 Since commanders of the accused make the legal decisions, it is argued that they are more likely to side with the parties under their command. Moreover, they may not look favorably on victims who make serious allegations against individuals they know; thus, they may retaliate.

It is rare that a commander will refuse to pursue an allegation of sexual assault, throw out a conviction, or significantly reduce a sentence in the current climate of harsh scrutiny and repercussions.33 In contrast to the allegations of critics, commander control is actually the reason for the comparatively high prosecution rate for sexual assault in the military versus broader society. Commanders have felt the pressure and responded by forcing prosecutors to push forward on cases that would otherwise not be pursued. Furthermore, the advent of the SARC and SVC positions increases commander accountability since these fairly independent actors can now be involved in sexual assault cases and protect the interests of victims.

Concerns over commander control are nonetheless valid. Such central control flies in the face of the more objective and removed prosecutorial offices in civilian legal systems that most see as more effective in administering justice.

Yet there are key concerns when discussing military law, with one being that the military legal system’s mandate is not only to administer justice, but also to maintain the discipline of a fighting force. The Supreme Court has explicitly acknowledged this function.34 Building on this, centralized command is an important factor in maintaining the discipline of any group. Commanders might find it difficult to exercise the full control over their units that is necessary in combat situations if Servicemembers know there is a powerful outside legal authority that can reach in and undermine leadership at any time. The elimination of commander control of the military system only in peacetime—and domestically—may come to mind as a compromise, but it also has issues. Fighting forces seek to train and operate at all times within the command structures that will be in place during combat situations. This helps to eliminate confusion and second-guessing when it matters most. It also helps to facilitate efficiency and field the most powerful fighting force for the defense and projection of national interests.

Irrespective of the current criticisms of the military justice system, it has developed by leaps and bounds over the last few decades and has come to resemble civilian systems. Modifications to it are therefore not likely to have much impact on overall sexual assault numbers. The keys to this are stopping these crimes in the first place and giving victims the initial assistance they need to recover and assess their legal options going forward. Therein lies the rub. If there is a trial involving sexual assault charges, the military has already failed. Someone has suffered.

Endgame: The Military Petri Dish

With this in mind, it is time the true potential of the military’s sexual assault crisis is realized. While it is a tragedy of grand proportions, the attention and resources being directed toward this problem intermix with the military’s centralized command structure to create the opportunity for incredible change.

The military has consistently operated as somewhat of a petri dish for societal reform. It is a tightly controlled subsection of the Nation able to respond quickly to and implement change (though this potential is not always realized). The best example is desegregation.35 While the Civil Rights movement was just gaining steam, the Armed Forces, under the direction of executive orders, had already fully integrated their units by 1954. They also established rights equivalent to the Miranda rights in the civilian system. While the Services have not always been at the forefront of change, their ranks have offered a staging ground for important societal developments. The military has helped push the gender equality discussion through women excelling in traditionally male positions and facing challenges in the Services.36 It has highlighted discrimination based on sexual orientation through the implementation and repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” and actions prior to that policy.37 And it is confronting the sustainability of current retirement benefit programs.38 How the military has handled these situations greatly influences how society at large responds. Likewise, how it handles the problem of sexual assault will have great influence.

Soldiers of 17th Field Artillery Brigade, 7th Infantry Division, participate in situational awareness training as it applies to sexual harassment and assault response and prevention (U.S. Army/Mark Mirandasb)

DOD has a massive budget and infrastructure and therefore has the resources to implement many possibly radical changes in seeking to prevent sexual assault and care for victims, as evidenced by the programs it has already enacted. The Pentagon is also less susceptible to political whims than civilian legal systems in the manner in which it tackles this problem. Military leaders are more able to implement programs without the fear that failure will cost them the next election. Especially in the current climate, they are highly influenced to try almost anything to stem the tide of sexual assault in their commands.

This situation presents a massive opportunity for broader society. The military is now fertile terrain for groundbreaking research and approaches aimed at addressing sexual assault. This is the perfect chance for societal actors to engage this issue without risking their own necks and resources. Civilian victims services, universities, law enforcement agencies, and other actors that combat sexual assault and are equally interested in solutions should team up with the military, share data, and propose avenues to pursue. The results of these efforts will be useful to all parties and will allow civilian actors to avoid programs that have proved unsuccessful and push for those that are effective.

Likewise, the military should be reaching out to these entities and anyone else it can, including foreign armed forces. It is discouraging that top military officers have acknowledged their ignorance of the sexual assault programs being undertaken abroad.39

President Barack Obama stated, “We have to be determined to stop these crimes because they have no place in the greatest military on Earth.”40 They also have no place in the greatest country on Earth, and the campaign against sexual assault taking place in the military should be viewed as an impetus for broader change. There exists the potential to produce incredible results, allow America to catch up with other developed nations, and perhaps even become an example for protecting people from some of the most societally degrading acts. JFQ

Notes

- See Karen Parrisch, “Sexual Assault Solutions Include Everyone, Hagel Says,” American Forces Press Service, July 1, 2013.

- Micah Zenko and Amelia Mae Wolf, “Our Military, Ourselves,” Foreign Policy, May 21, 2013, available at <www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2013/05/21/our_military_ourselves>.

- Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, “Criminal Victimization 2011,” October 2011, available at <www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cv11.pdf>.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention, “National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, 2010 Summary Report,” November 2011.

- Department of Defense (DOD), DOD Personnel and Procurement Statistics, “Armed Forces Strength Figures for January 31, 2013,” available at <http://siadapp.dmdc.osd.mil/personnel/MILITARY/ms0.pdf>.

- Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, “Criminal Victimization 2009,” October 2010, available at <www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cv09.pdf>.

- Bonnie S. Fisher, Francis T. Cullen, and Michael G. Turner, “The Sexual Victimization of College Women,” Minnesota Center Against Violence and Abuse, 2000, available at <www.mincava.umn.edu/documents/college/college.pdf>.

- Medical University of South Carolina, National Crime Victims Research & Treatment Center, Drug Facilitated, Incapacitated, and Forcible Rape: A National Study, February 1, 2007, available at <www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/219181.pdf>.

- Rosa Brooks, “Is Sexual Assault Really an ‘Epidemic’?” Foreign Policy, July 10, 2013.

- Gordon Lubold, “Are the Chiefs Swimming Upstream on Sexual Assault? 73 Percent of Victims Are Junior Enlisted; Happy Birthday Southcom! Jill Kelley, Suing; What Caused That Cargo Plane to Crash in Kabul in April; and a Bit More,” Foreign Policy, June 4, 2013.

- DOD, Sexual Assault Prevention and Response (SAPR), Department of Defense Annual Report on Sexual Assault in the Military: Fiscal Year 2012, April 15, 2013.

- DOD, SAPR, Department of Defense Annual Report on Sexual Assault in the Military: Fiscal Year 2010, March 2011.

- DOD, SAPR, Department of Defense Annual Report on Sexual Assault in the Military: Fiscal Year 2011, April 2012.

- DOD, SAPR, Department of Defense Annual Report on Sexual Assault in the Military: Fiscal Year 2009, March 2010.

- Lindsay L. Rodman, “Fostering Constructive Dialogue on Military Sexual Assault,” Joint Force Quarterly 69 (2nd Quarter, April 2013).

- See Sexual Assault Awareness and Prevention, available at <www.defense.gov/home/features/2012/0912_sexual-assault/>.

- See Reporting Options, Restricted Reporting.

- DOD Annual Report on Sexual Assault in the Military: Fiscal Year 2010.

- See DOD Instruction 6495.02, para. 4.f and enclosure 6, March 28, 2013, available at <www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/corres/pdf/649502p.pdf>.

- See “D-SAACP,” Sexual Assault Advocate Certification Program, available at <www.sapr.mil/index.php/d-saacp>.

- See “About,” Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Office, available at <www.sapr.mil/index.php/about>.

- See “SAAM,” Sexual Assault Awareness Month, available at <www.sapr.mil/index.php/saam>.

- See David Salanitri, “AF Provides Special Counsel to Sexual Assault Survivors,” Air Force Public Affairs, May 24, 2013, available at <www.af.mil/news/story.asp?id=123350021>.

- See DOD, “Department of Defense Press Briefing with Secretary Hagel and Maj. Gen. Patton on the Department of Defense Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Strategy from the Pentagon,” News Transcript, May 7, 2013, available at <www.defense.gov/transcripts/transcript.aspx?transcriptid=5233>.

- See Steve Liewer, “Air Force Sex Crimes Victims Get Legal Boost,” Omaha World-Herald, July 7, 2013, available at <www.omaha.com/article/20130707/NEWS/707079922>.

- See Kristin Davis, “Special Victims Counsel ‘A Huge Step Forward,’” Air Force Times, May 22, 2013.

- Sexual Assault Awareness and Prevention, available at <www.defense.gov/home/features/2012/0912_sexual-assault/>.

- Marisa Taylor and Chris Adams, “Military’s Newly Aggressive Rape Prosecution Has Pitfalls,” McClatchy Newspapers, November 28, 2011.

- Nancy Montgomery, “AF Strengthens Sex Assault Prosecutions,” Stars and Stripes, January 10, 2013, available at <www.military.com/daily-news/2013/01/10/af-strengthens-sex-assault-prosecutions.html>.

- Sexual Assault Awareness and Prevention, available at <www.defense.gov/home/features/2012/0912_sexual-assault/>.

- Matt Collins, “Rape and the Ethics of Adultery, or How the Military Hides Its Rape Problem,” Foreign Policy, August 28, 2012.

- See Megan R. Wilson, “Gillibrand: ‘Culture Change’ Needed to End Military Sexual Assaults,” The Hill, June 9, 2013, available at <http://thehill.com/video/senate/304377-gillibrand-military-sexual-assaults-a-crisis>.

- See Donna Cassata, “Claire McCaskill Blocks Air Force Officer Susan Helms’ Nomination Over Military Sexual Assault,” The Huffington Post, June 7, 2013.

- See Parker v. Levy, 417 U.S. 733, 744, 758 (1974), available at <http://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/417/733/case.html>.

- See DOD, “Military Integration Timeline.”

- See “Highlights in the History of Military Women,” Women in Military Service for America Memorial Foundation, Inc., available at <www.womensmemorial.org/Education/timeline.html>.

- >See DOD, SAPR, Human Resources Strategic Assessment Program, “2012 Workplace and Gender Relations Survey of Active Duty Members,” March 15, 2013.

- See James Joyner, “Military Retirement Overhaul,” Outside the Beltway, July 25, 2011, available at <www.outsidethebeltway.com/military-retirement-overhaul/>.

- See Alex Seitz-Wald, “Answer to Military’s Sexual Assault Problem may be Overseas,” Salon, June 5, 2013.

- Tom Watkins, “Hagel: Scourge of Sexual Assault ‘Must be Stamped Out,’” CNN.com, May 25, 2013, available at <www.cnn.com/2013/05/25/politics/new-york-hagel-west-point>.